Post by Greyson Moore from Portland State University and Aaron Eisen from the National University of Natural Medicine and Oregon Health & Science University

As an icy snowstorm blanketed much of North America, including Northwest Oregon, our informed and enthusiastic Noggin volunteers were excited to visit (virtually) the warm Hawaiian island of Oahu to talk brain research – and art! – with curious fifth graders at Waikiki School!

LEARN MORE: Ho brah, he lolo maoli kēlā!

LEARN MORE: Desperately Seeking Rasa

Greyson Moore and Aaron Eisen, recent graduates of Portland State University, are both from Hawaii and responded to SOME of the students’ many questions.

Check out the complete list of inspiring, challenging thoughts, ideas and questions from Waikiki 5th graders at the bottom of this post.

TICKLING!

How are some people so ticklish and some people are not? Is it your brain telling you it’s ticklish?

From Aaron

One study found that an area of the brain involved in involuntary responses known as the hypothalamus is activated when someone is tickled, suggesting that tickle response is also involuntary and acts like a reflex. Felt aspects of tickling, including the anticipation, and the tickling itself, set off lots of activity in a deep area of the brain known as the insula, where emotionally significant sensations from our bodies are mapped. In this study, scientists actually tickled people’s feet as they lay in an MRI machine, which recorded these responses in their brains!

It also seems that the brain may consider tickling to be a painful experience (!!), suggesting that you might laugh when being tickled for the same reason you say “ouch” when you are injured.

LEARN MORE: Exploration of the Neural Correlates of Ticklish Laughter by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Past researchers have also shown that the brain responds differently to tickling or verbally telling a joke. This supports the hypothesis that ticklishness is a reflex response.

LEARN MORE: Different Types of Laughter Modulate Connectivity within Distinct Parts of the Laughter Perception Network

Moreover, some people are more ticklish than others.

People tend to be more ticklish when they are caught by surprise which may explain why we cannot effectively tickle ourselves. Also, a person’s mood seems to be related to how ticklish a person is at a given time. A study on mice in 2016 found that anxiety made the mice less ticklish. Therefore ticklishness can also depend on who is tickling you. Tickling a close friend is probably less anxiety provoking for them than being tickled by a stranger, likely making the tickle response stronger.

LEARN MORE: Neural correlates of ticklishness in the rat somatosensory cortex

By the way, rats LAUGH when you tickle them!

SLEEP & DIET

What can I do to have a super healthy brain?

From Greyson

The brain is constantly receiving, interpreting, and delivering information. With many different parts that execute many different functions, there are a ton of things you can do to have a super healthy brain!

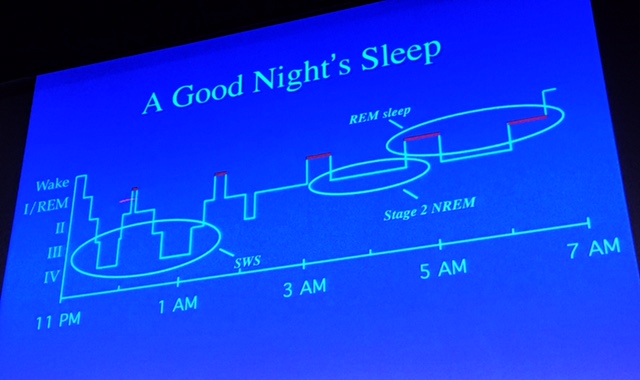

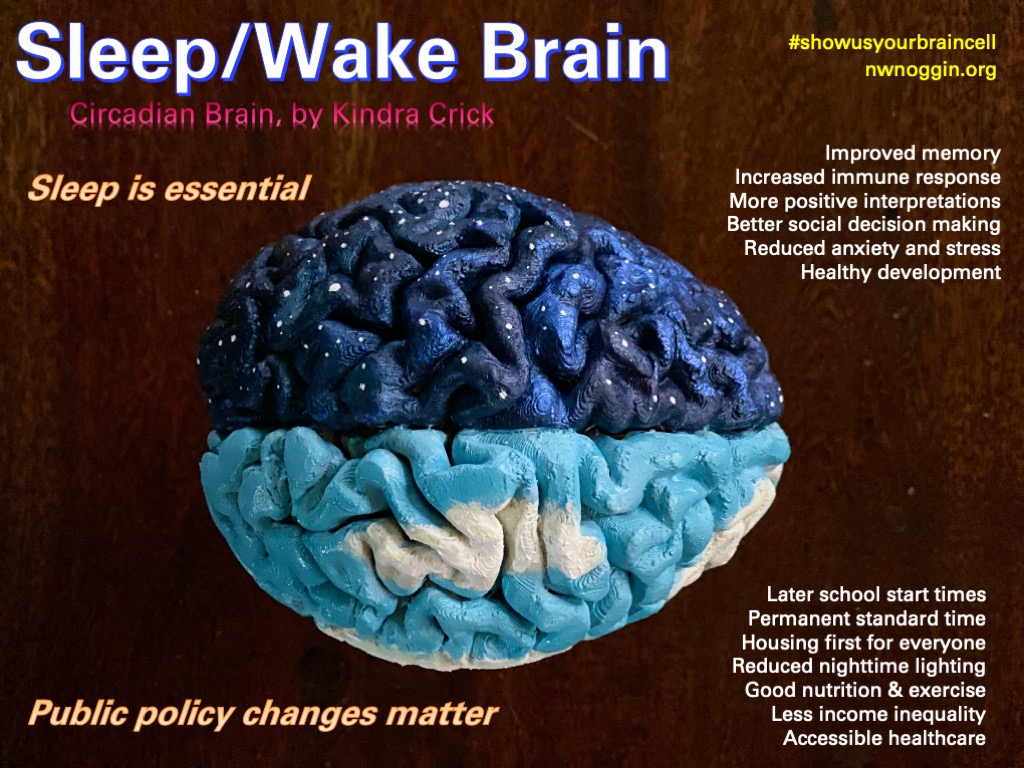

One of the most important things for a healthy brain is quality sleep at regular intervals.

Research suggests that each of the five stages of sleep evolved to execute particular functions. A lack of sleep can start to negatively affect our ability to learn new information, as well as our ability to encode and create new memories. Missing sleep weakens the body’s immune system, interferes with hormone balance, and affects our emotional well-being.

Get a good night’s sleep: Sleep deprivation makes you perceive new experiences more negatively the next day!

Regulating your sleep helps your brain run more efficiently, allowing it to sort through all the ‘noise’ or excess sensory information it has picked up throughout the day. When you sleep your brain gets to store experiences it deems important as memories while flushing out useless information, making you more receptive when more useful information comes your way.

“If you like be akamai, make sure you get choke shut eye”

LEARN MORE: Cognitive Neuroscience of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Noggins in Nod – The Science of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Beyond Memory: The Benefits of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Oregon wants to increase sleep deprivation and winter misery

In addition to sleep, your diet is extremely important in maintaining a healthy brain. The gut, or gastrointestinal tract produces 95% of the body’s serotonin, a neurotransmitter/hormone that is extremely important and widely used throughout the body. It is used to modulate mood, feelings of happiness, and overall well-being. Serotonin also allows neurons and other nervous system cells to communicate with one another. What is going on in your gut has direct influence on your emotions. The production of serotonin in the gut is impacted by the billions of ‘good bacteria’ (probiotics and prebiotics) present, which are associated with substances introduced to the body through your diet. These good bacteria also protect you against toxins and activate neural pathways that allow the gut and brain to communicate. This collection of bacteria is called your gut microbiome, and its maintenance plays a large role in keeping your brain healthy.

“If you stay grinding only junk food, guarantee stay in a supah junk mood!”

LEARN MORE: Nutritional psychiatry: Your brain on food

LEARN MORE: Gut Bacteria Can Influence Your Mood, Thoughts, and Brain

LEARN MORE: Serotonin Involvement in Physiological Function and Behavior

JOIN US (online and free!) @ NOGGINFEST (Saturday, March 20) to learn more about the gut/brain connection!

DREAMS

Why do we dream? How does our brain decide what goes in our dreams? Why does the brain not remember things that happened a long time ago?

From Aaron

It is thought that dreaming is a result of our brain storing memories throughout the day while we sleep. Throughout the day, we take in so much information until we reach a point where it is hard to take in any more information (this is one reason it’s harder to think/remember things after a long day). You could think of this as being like a dimmer switch for a light. We start out the day (assuming you got a full night’s sleep) with the switch all the way off, and it slowly builds up throughout the day until the switch is all the way up by the time you are ready for bed. While you sleep, your brain sorts this information and decides what is not important (to discard) and what is important (and should be stored in long term memory). This is why it is hard to remember what you ate for lunch a month ago, but you can remember an important event that happened to you a long time ago. It seems that dreams are involved in this process. When you brain files away new memories with old ones, it can reactivate these old memories which may explain why we can have such unusual dreams (i.e. with people/places we haven’t seen or thought of in a very long time).

LEARN MORE: Relationship between Dreaming and Memory Reconsolidation

DECISIONS

How do we make decisions?

From Greyson

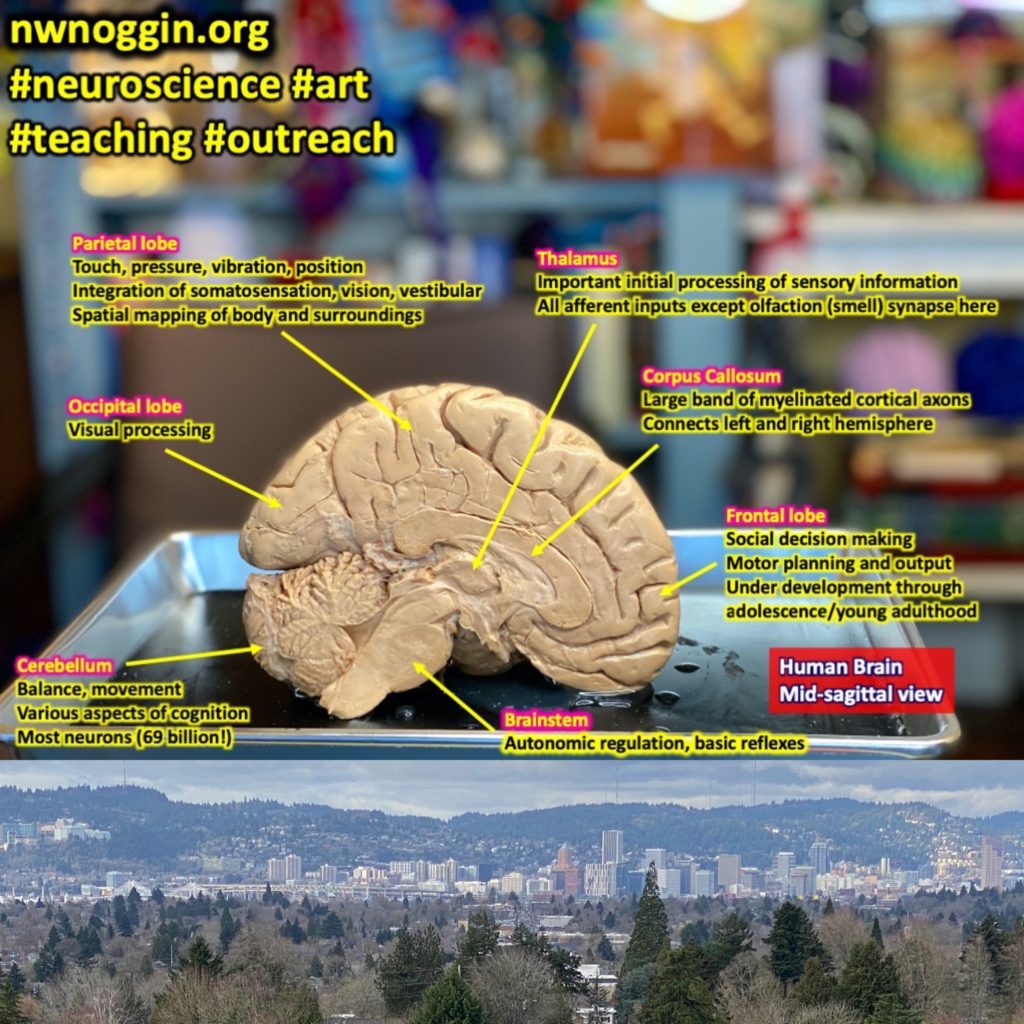

In neuroscience, processes like decision making are considered “executive functions.” These executive functions occur when several areas of the brain are required to perform a task to deliver a timely and coordinated response. This type of brain activity is associated with the frontal lobe of the brain, more specifically, the prefrontal cortex. Depending on the situation and present stimuli, the processes of decision making change. Our brain gathers up all the responses to our surrounding environment from the different areas in our brain, and then translates them into physical and cognitive response – actions and thoughts. Decision making happens on both the conscious and unconscious levels, and while critical areas of executive function are in the frontal lobe, decision making always involves the activity of multiple, distributed areas in the brain.

There are also different neural systems that value immediate prospects (what do I get right now?) and future prospects simultaneously. Both of these systems working together in real time allow us to make informed decisions about immediate results and future consequences.

As a child, your processes of decision making and other areas of executive function are developing, and learning from real world experiences, so we (generally!) get better at making informed decisions as we grow.

“Our mana’o makes real fast kine choices in da frontal lobe”

LEARN MORE: Reasoning, Learning, and Creativity: Frontal Lobe Function and Human Decision-Making

LEARN MORE: The Functional Neuroanatomy of Decision Making: Prefrontal Control of Thought and Action

LEARN MORE: The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making

SMARTS

What is intelligence? Is it true that bigger brains are smarter than smaller brains?

From Aaron

Intelligence is an interesting and controversial concept that has been measured in various ways (general cognitive ability, mental ability, and IQ). Many “intelligence” tests were deliberately designed to promote racial segregation. Some researchers disagree that there is any single measure of intelligence, and argue that are different “types” of intelligences. Dr. Howard Gardner, for example, suggested there are 8 different types of intelligence (linguistic, logical/mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalist). In line with this theory, research has shown that people use their brains differently to solve the same mental tasks. Also, it seems that intelligence does not happen in any single brain area but rather it is the result of different brain networks working together, especially our frontal lobe networks. People who score higher on a specific personality trait known as “openness to experiences” also tend to score higher on various psychological measures of intelligence. People more open to experiences may regularly encounter novel (new), varied challenges, and thus train their developing brains in more diverse environments. In other words, trying new things, making mistakes, and learning what works and what doesn’t, is a way that the brain becomes more “intelligent” over time – better able to adapt to one’s environment.

LEARN MORE: Taking a Stand: The Genetics Community’s Responsibility for Intelligence Research

LEARN MORE: The IQ test has a dark history

LEARN MORE: Multiple Intelligences in Teaching and Education: Lessons Learned from Neuroscience

LEARN MORE: The neuroscience of human intelligence differences

LEARN MORE: Survey of Expert Opinion on Intelligence: Causes of International Differences in Cognitive Ability Tests

LEARN MORE: Role of test motivation in intelligence testing

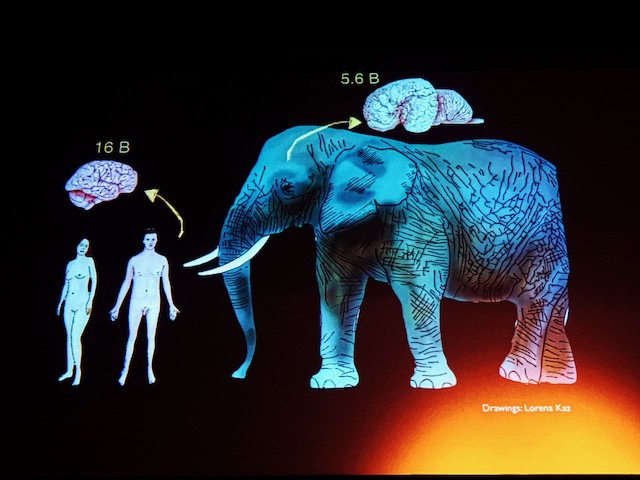

It is not necessarily true that bigger brains are smarter than smaller brains. For example, the sperm whale has the largest brain of any animal species but they are not “smarter” than humans. Rather, it seems that bigger brains go in animals with bigger bodies as there is a lot more body to control! For example, an elephant’s brain has more brain cells than a human brain but most of these brain cells work to coordinate the elephant’s movement rather than cognition. On the other hand, birds have much smaller brains that are very dense with brain cells as they need to be lighter so the bird can fly. The size of the brain is not as important as the ratio to size/density of brain cells – and also where in the brain those cells are found!

LEARN MORE: Soup for Brains!

LEARN MORE: The Human Brain in Numbers: A Linearly Scaled-up Primate Brain

PERCEPTION

How does your brain react to moving objects?

From Greyson

Our eyes are extraordinary.

We are visually driven primates, and most of us rely on the remarkable ability of specialized sensory neurons called photoreceptors to capture narrow wavelength ranges of electromagnetic energy reflected from the people and objects in our environment.

Your eyes track movement best through a specific photoreceptor known as rod cell. Rod cells are found at the back of each eyeball, in a sheet of cells called the retina. There are roughly 90 million of these specialized sensory neurons located in each eye! They are mostly in the periphery of the retina, which means that they are not found in a focused central area (unlike other photoreceptors called cone cells). Rod cells are best at tracking movement and focusing on objects in lower light settings.

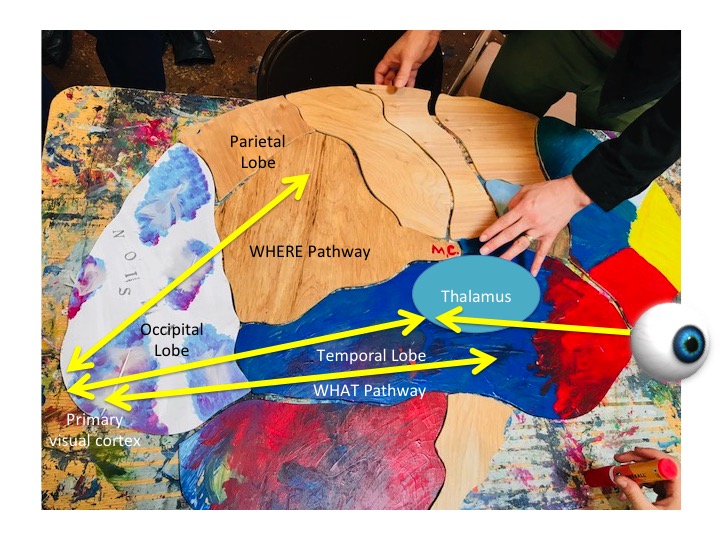

The visual information received in the eye is sent via neurons to the occipital lobe at the back of your brain, and also shared with other brain areas to identify the moving object and determine whether or not it poses an immediate threat. The perception of threat occurs in an area of the brain called the amygdala, and the quick orienting of your head, neck and eyes to dangerous or unexpected stimuli is accomplished by networks of neurons in your brainstem – in a set of bumps (“colliculi” in Latin) on the back of your brainstem called the superior colliculi.

Visual information that arrives in the occipital lobes (in primary visual cortex, or V1) also passes through the parietal and temporal lobes as well, which are responsible for spatial mapping (parietal) and object recognition (temporal). These networks lets you consciously identify what you’re looking at, and where it is in relation to you!

“When you see the braddah kimo drop knee out da barrel, guarantee stay using the rod cells brah”

LEARN MORE: Hallucinations @ HeLa High

LEARN MORE: Tagging the temporal lobe

Complete list of student questions!

● How does the brain dream at nighttime?

● How does the brain develop memories?

● What if our body didn’t have sensory nerves, but had nerves?

● What if our body didn’t have nerves but had sensory nerves?

● Why do younger people remember more memories than older people?

● Does the brain control our emotions, thoughts and behaviors?

● What is the brain made of?

● When the brain is dead, does it change color?

● Does the brain grow larger as you keep on growing?

● What colors can brains become?

● My first question for the neuroscientist is how does your brain react to loud noises.

● My second question for the neuroscientist is how does your brain react to moving objects.

● How does your brain store important information?

● Could you switch your brain with something similar?

● Would the word color reading experiment be easier or harder for preschoolers?

● If one of my senses didn’t work would I panic if I did the hole in the hand experiment?

● Why do we have dreams?

● Why do we get excited?

● What does the brain feel like, is it mushy, is it soft?

● Is the brain really pink like in the movies?

● Why does the brain panic?

● What does the brain do when it becomes overloaded?

● If two people switched brains what would happen?

● Could you replace the brain with something the same shape and texture?

● How does the brain control our body?

● If we get a new brain would we forget our memories?

● I wonder what would happen if you swapped your brain with someone else. Would you have his memories? Why or why not?

● Why does my brain tell my body what to do?

● How does my brain have room for my memories?

● Are nerves hard like thin bones or are they soft and stringy like yarn?

● When we get headaches, are they happening in our brain and if so why and how?

● Why do we dream?

● What sports require really good reaction time and how does our brain learn how to react?

● How does our brain know that our body is in distress?

● How do signals travel through sensory nerves to the brain?

● What does a brain feel like?

● What makes a brain function your body?

● Is it true that bigger brains are smarter than smaller brains?

● How does the brain not have any moving parts?

● Why do we have blood in our brain?

● Which is the most important part in the human, brain or heart?

● How fast does the brain make decisions, give information and control your muscles to other parts of the body?

● How come the brain is in our head?

● What’s the difference between a smart brain vs. a not smart brain?

● How many parts of the brain are there and what are they called?

● How does the brain send commands to the other parts of your body?

● I wonder why we don’t just run out of storage in our brain?

● Why are we able to work with one muscle?

● Why is the brain slimy?

● Where do brains come from?

● How does our brain control us?

● Is our brain the only body part that controls our body?

● When you sleep, does your brain sleep?

● When you dream does your brain memorize stuff and put it together in the dream?

● What would happen if we couldn’t feel pain from our nervous system?

● What if we didn’t have our nervous system?

● How many cells does the brain have?

● How does the brain work? Does it have anything like a motor?

● How does our brain decide what goes in our dreams?

● Why does the brain not remember things that happened a long time ago?

● The brain controls our body, is there a way to alter the brain to become some sort of godly figure?

● What if there was some sort of zombie apocalypse, would we be mindless?

● Have you ever touched a brain?

● What is inside the brain?

● Where does the brain keep memories?

● Why does the body parts get weaker when we get older?

● How do blue light glasses actually work when playing video games?

● Why do we get happy or mad when you win or lose in video games? It does feel like I accomplish something, but it’s just a game.

● When we’re scared, why do we scream?

● How can someone get over dyslexia?

● How does your brain flip the pictures that you see?

● Why do brains look like they have those tubes?

● How can our brain contain all these memories?

● Why does our brain use up so much energy?

● What if our body didn’t have sensory nerves, but had nerves?

● What if our body didn’t have nerves but had sensory nerves?

● Can a person survive without a brain?

● Are there different types of brains?

● Who named the brain?

● Do we have infinite memory?

● How does the brain store memories?

● How does the brain control your body?

● What would happen if our brains were shaped differently than they are right now? Would we still act the same?

● Are animal brains similar to human brains?

● Does the brain grow larger as you keep on growing?

● What colors can brains become?

● What if the brain was 2x smaller?

● What if the brain was 2x bigger?

● Is our brain the hardest worker of our body part?

● How does it store so many memories when it’s so small?

● What would happen if your brain could not make decisions?

● What if humans’ reaction time was a second?

● What would it be like if you switched, you’re brain with a dog’s brain?

● Why do we think certain things are beautiful and some things are not?

● How do we store all of our memories in our brains?

● Why do we dream?

● Does the brain have a limit to storing and learning new things?

● Why do people lose their memory?

● How will you figure out how the brain works?

● Where do you get brains to dissect?

● Why does the brain have memory (how does it remember things)?

● Why do some brain think differently?

● What is the brain made of?

● When the brain is dead, does it change color?

● My first question for the neuroscientist is how does your brain react to loud noises?

● My second question for the neuroscientist is how does your brain react to moving objects?

● Do we need our brain to help us walk and talk?

● Every one of our memories in our brain do they disappear or just stay in our head?

● How do brains work?

● Why are brains the shape it is?

● Can the Brain learn anything?

● How many parts are in the Brain?

● How does the brain dream at night time?

● How does the brain develop memories?

● What can I do to have a super healthy brain?

● What are brain waves?

● How do we make decisions?

● What is intelligence?

● Why do younger people remember more memories than older people?

● Does the brain control our emotions, thoughts and behaviors?