Post written by New/Mixed media artist Kit S. Carlton. Kit also joined OHSU Behavioral Neuroscientist Sydney Boutros for a collaborative Noggin presentation in October 2019: Memory, Poetry, Brains.

Going places!

In the first two weeks of February, a team of neuroscientists, students, educators, artists and classrooms of kiddos converged to contemplate all things art and brains. These events facilitated by NWNoggin provided a much-needed escape from the deluge of covid drudgery and isolation.

LEARN MORE: Uploading your brain from Vancouver

LEARN MORE: Ho brah, he lolo maoli kēlā!

During these sessions it was made quite obvious that kids don’t just say the darnedest things; they often ask some of our deepest-seated questions without hesitation – how utterly refreshing!

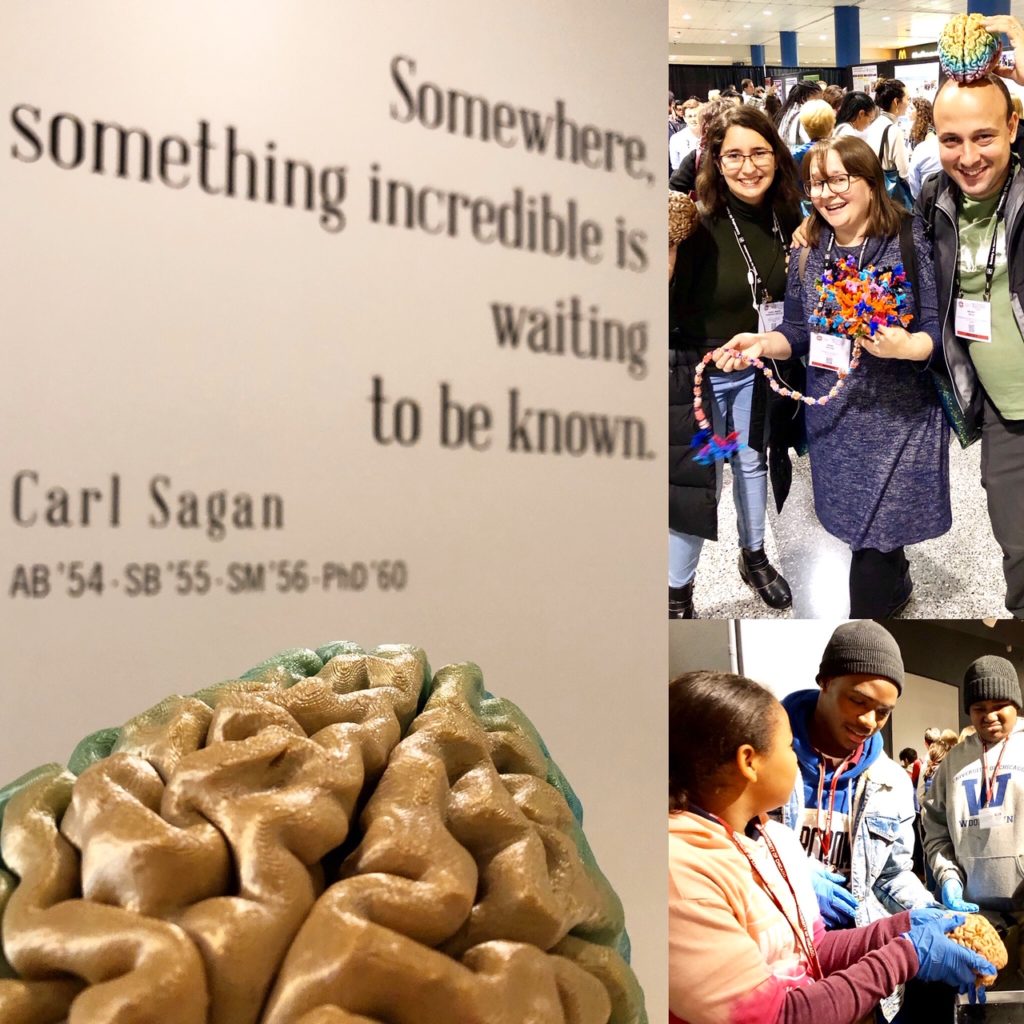

The late and renowned astrophysicist, Carl Sagan, during a Studio 2 interview once exclaimed, “You go talk to kindergarten kids or first grade kids; you find a class full of science enthusiasts. They ask deep questions. What is a dream? Why do we have toes? Why is the moon round? What is the birthday of the Earth? Why is the grass green? These are profound, important questions. They just bubble right out of them…”

LEARN MORE: Carl Sagan and the Search for Life

While the kids were a bit older than those quoted by Sagan, hearing questions proposed by these flexible minds truly felt like sitting in a room full of young “big-think” thinkers, philosophers, astronauts, scientists, artists and their ilk.

In other words, the experience was completely exhilarating!

So many mind-bending questions!

One question in particular kept emerging about whether or not it was possible to transplant the human brain into another body either physically or computationally. Hello future AI engineers or Isaac Asimovs. We see you.

Another from a potential Freudian or Jungian psychologist quizzically pondered: “Where do thoughts go when we forget them?” Perhaps the unconscious or the collective unconscious, anyone?

And while these questions are profound in the deepest sense of the term, one in particular arose that has long haunted the minds of philosophers, artists, evolutionary biologists and more recently neuroscientists alike:

What makes something beautiful?

A fairly unanimous theory of beauty presupposes that there is not a singular or universal concept of beauty because what makes something beautiful to an individual is an amalgamation of culture, environment and subjective tastes.

LEARN MORE: The nature of beauty

LEARN MORE: What is Beauty?

However, in an emerging branch of neuroscience, neuroaesthetics, some neuroscientists attempt to make a case for the universality of underlying neural mechanisms which process fundamental aesthetic principles of beauty. Whereas the Gestalt psychologists have long since paved the foundation of perceptual organization through laws such as: similarity, Prägnanz, proximity, continuity, closure and common region, neuroaesthetician V.S. Ramachandran adds to the theory of aesthetics by outlining nine such principles that enable rasa in his captivating book, ‘The Tale Tell Brain.’

LEARN MORE: V.S. Ramachandran’s Tales Of The ‘Tell-Tale Brain’

What is rasa?

Rasa is a Sanskrit term when translated into English loosely means, “capturing the very essence, the very spirit of something, in order to evoke a specific mood or emotion in the viewer’s brain.” According to Ramachandran, “if you want to understand art, you have to understand rasa and how it is represented in the neural circuitry in the brain.”

Here’s a rundown of Ramachandran’s nine universal laws of aesthetics [please note the more laws utilized in an artwork yield greater propensities of rasa (aka the true goal of every great artist).

“Most people recognize that the purpose of art is not to create a realistic replica of something but the exact opposite. It is to deliberately distort, exaggerate—even transcend—realism in order to achieve certain pleasing (and sometimes disturbing) effects in the viewer. And the more effectively you do this, the bigger the aesthetic jolt.”

– V.S. Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain

Are there “laws” of aesthetics?

- 1. Grouping – the tendency of the visual system to group similar elements/features into clusters as it is speculated that grouping evolved to “defeat camouflage and to detect objects in clustered scenes.” (p.231)

- 2. Peak Shift – a.k.a., how our brains respond to exaggerated stimuli. Ramachandran suggests that abstractionists tap “into the figural primitives of our perceptual grammar and [create] ultranormal stimuli that more powerfully excite certain visual neurons in our brains as opposed to realistic images.” (p.241)

- 3. Contrast – this one is fairly self-explanatory and even if not, just take any image on your phone, go into edit, hit contrast and explore away.

- 4. Isolation – “when an artist emphasizes a single source of information—such as color, form, motion—and deliberately plays down or deletes other sources” i.e. sketches or doodles “standard physiology and psychology textbooks [instruct] that a sketch is effective because cells in your primary cortex, where the earliest stage of visual processing occurs, only cares about lines. These cells respond to the boundaries and edges but are insensitive to the feature-poor fill regions of an image…a sketch can be more effective because there is an attentional bottleneck in your brain…overlapping patterns of neural activity and the neural networks in your brain constantly compete for limited attentional resources. Thus when you look at a full color picture, attention is distracted by the clutter of texture and other details in the image.” But a sketch allows the viewer to focus wholly on the outline “where the action is.” (p. 250)

- 5. Peekaboo – or perceptual problem solving (a personal favorite principle to employ in my own work)—“[when looking at visual scenes], your brain is constantly resolving ambiguities, testing hypotheses, searching for patterns and comparing current information with memories and expectations…” (p.257) like solving a visual/perceptual puzzle which rewards the limbic system.

- 6. Abhorrence of Coincidences – as our brains constantly scan our environment to co-construct and shape our perceptual field of reality, structures which appear out of place or less probable in our accumulated schema when viewing an image such as a painting, etc. become less aesthetically pleasing aka “abhorrence for deviation from expectation”. Ramachandran uses an example of a landscape image where a tree is either off center (more pleasing and more probable in our environment due to its multi-angled vantage points versus one that is squarely in the center of the image which is less probable in reality and offers only one point of view.)

- 7. Orderliness – the “built-in need” our brains have for “impos[ing] regularity or predictability” (p.263)

- 8. Symmetry – that we derive pleasure from symmetry stems from an evolutionary biology theory that vision itself evolved “mainly for discovering objects, whether for grabbing, dodging, mating, eating or catching. [Our] visual field is always crammed full of objects: trees, fallen logs, splotches of color on the ground, etc.” (p.263) and given that attention is throttled in the brain there must be guidelines employed to ensure successful attempts at focusing attention. Symmetry is conjectured as one such guideline. That and parasites—but you should just pick up Ramachandran’s book for further explication.

- 9. Metaphors – Ramachandran speculates that “ordinarily there might be a translation barrier between left and right hemisphere’s language based, propositional logic and the more oneiric, intuitive “thinking”…, and great art succeeds by dissolving this barrier.” (p. 266) His speculations however, do seem to match up to my own experience of art creation and viewership. Perhaps this is why my preference is to create visual metaphors in lieu of those linguistic.

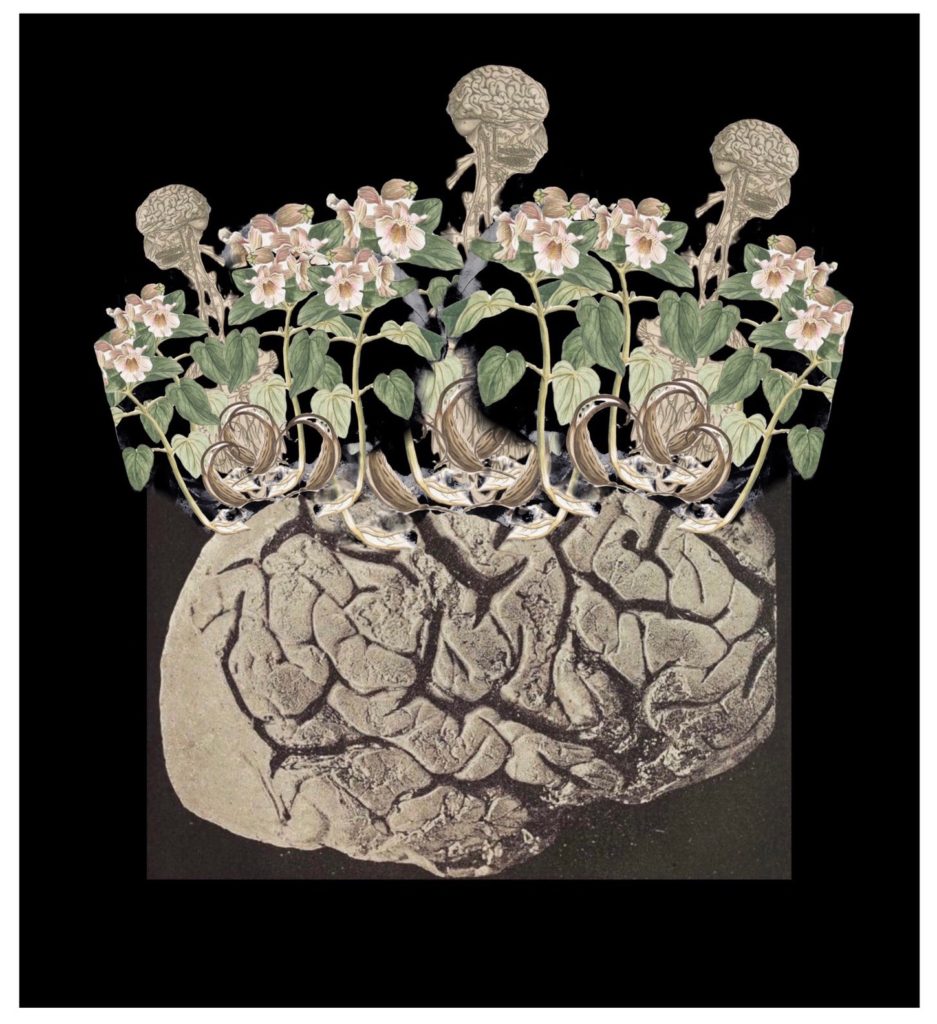

This image was created as a doodle during one of the sessions. Later the sketch was captured via photograph and used to construct a digital photomontage. In this image elements of color grouping, peak shift, contrast, isolation, peekaboo (in this work I personally see: a 1) fox, 2) a torso of a woman 3) a skull, 4) bear or a dog depending on the angle, and 5) a cat (possibly of the Cheshire variety)—wonder what you see or if you see any of these same objects—hence the fun), abhorrence of coincidence and metaphor [6) zoom in on the tree to see where the original sketch spans two pages but the way it is captured is reminiscent of the two hemispheres of the brain—a fairly apt metaphor, no?).

The Beauty of Art

The beauty of the ‘beauty of art’ lies in the rasa-echo of both artist and viewer and in the connectivity that shared experience creates.

Neuroaesthetics neurobiologist Anjan Chatterjee, reasons, “once you are in the same state as the artist, your brains are responding in a similar way.” Marc Rothko himself is notorious for saying, “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.” However we go about desperately seeking rasa, Chatterjee further intimates, “if we are deeply moved, if we really enjoy an art work, our neural responses are more similar then different even if that happened with a Rothko for you or a Hopper for me.”

LEARN MORE: Neuroaesthetics