Post written by New/Mixed media artist Kit S. Carlton & Ph.D. candidate Sydney Boutros from Behavioral Neuroscience at OHSU

Noggin Talks are back!

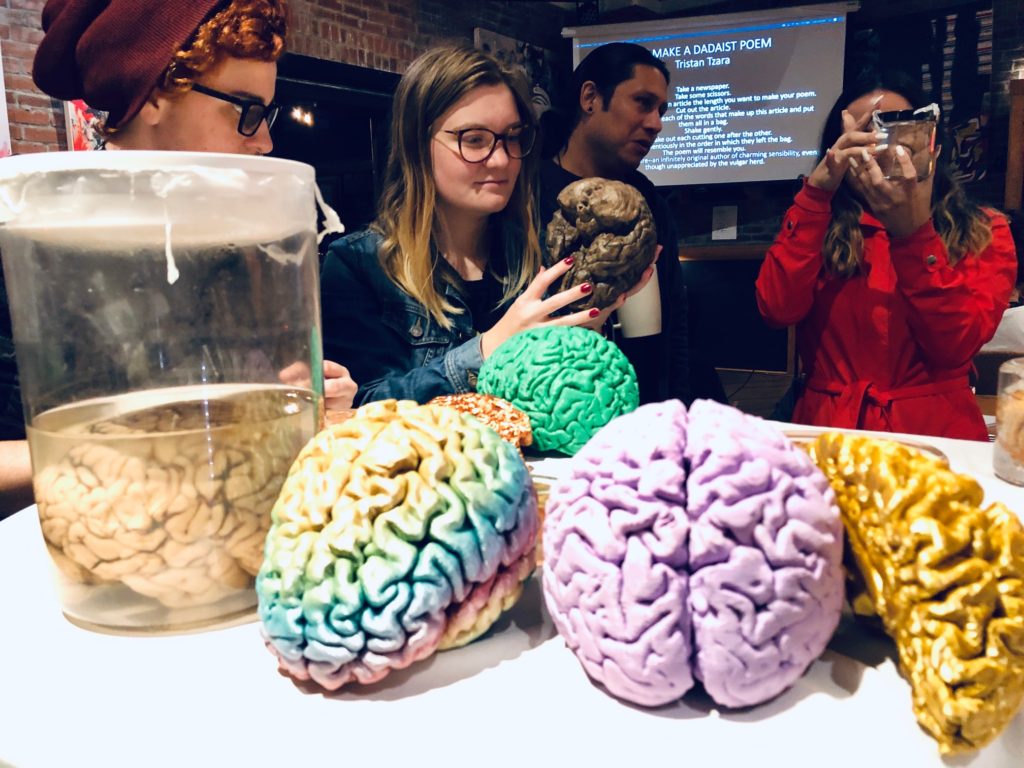

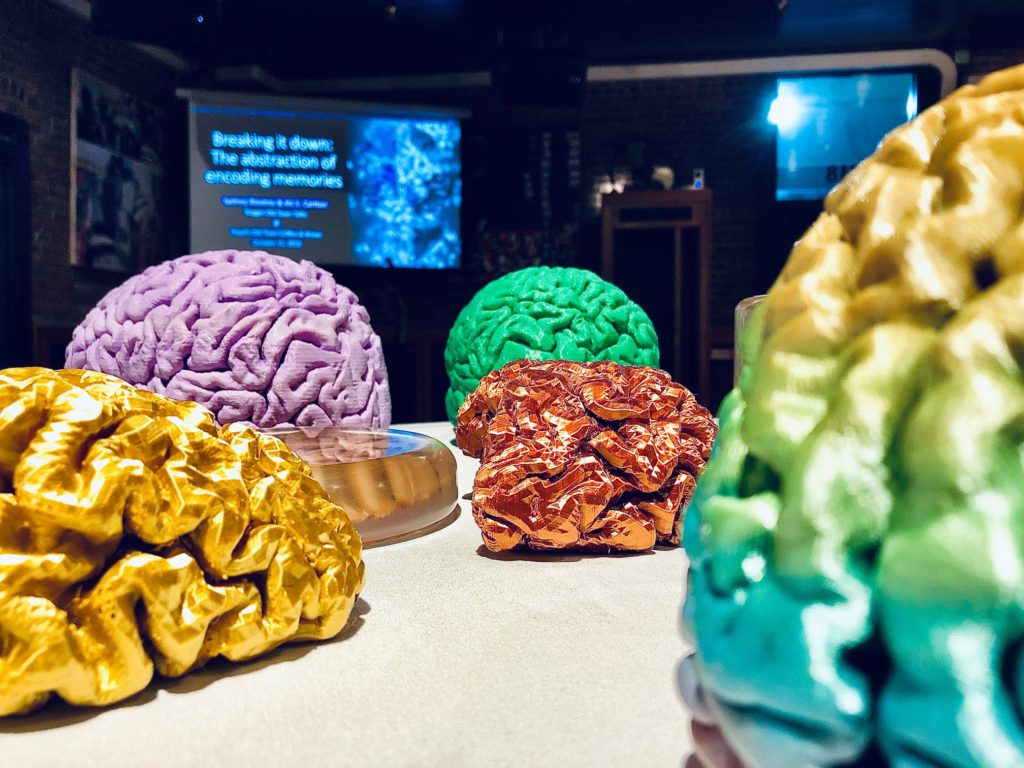

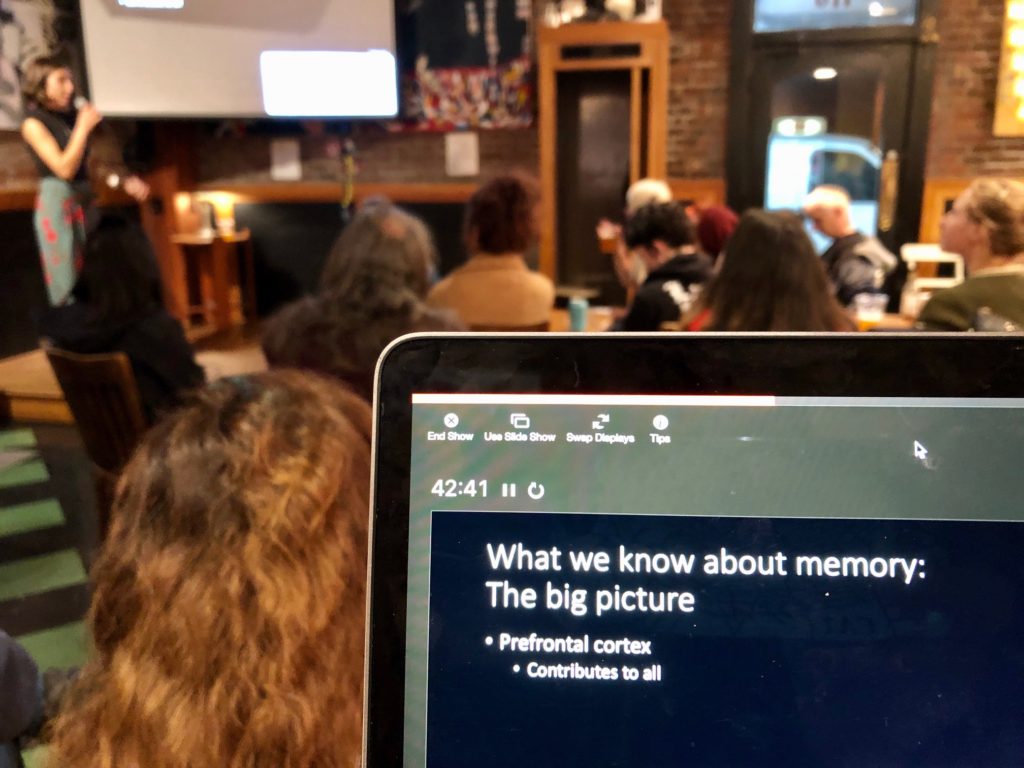

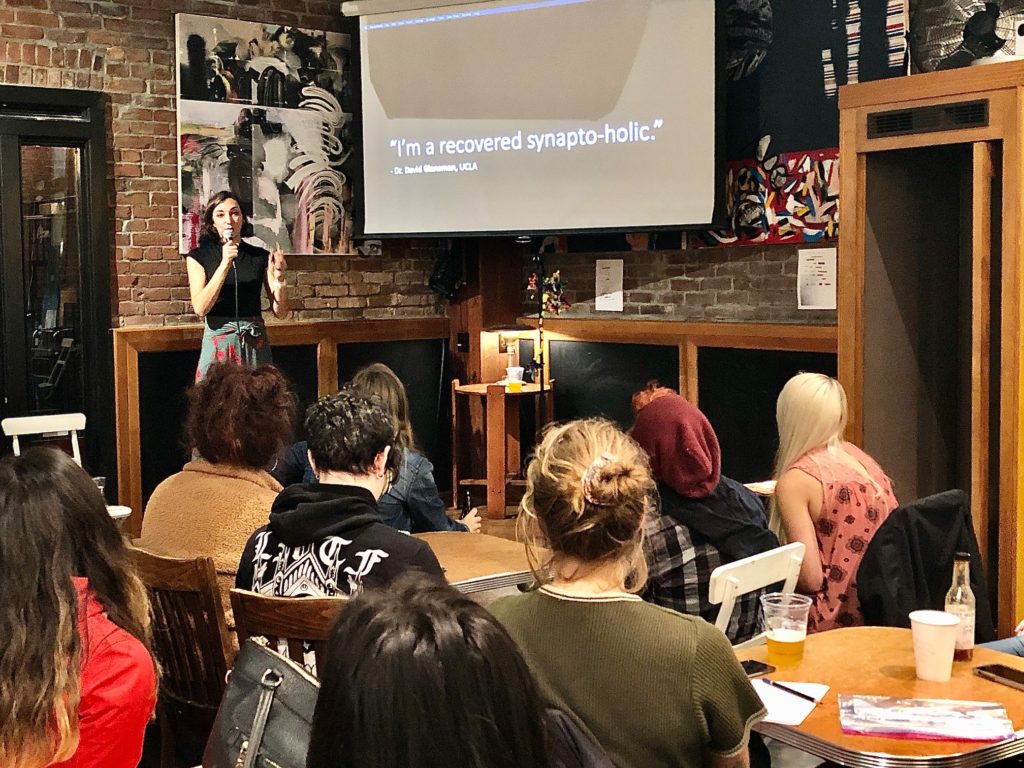

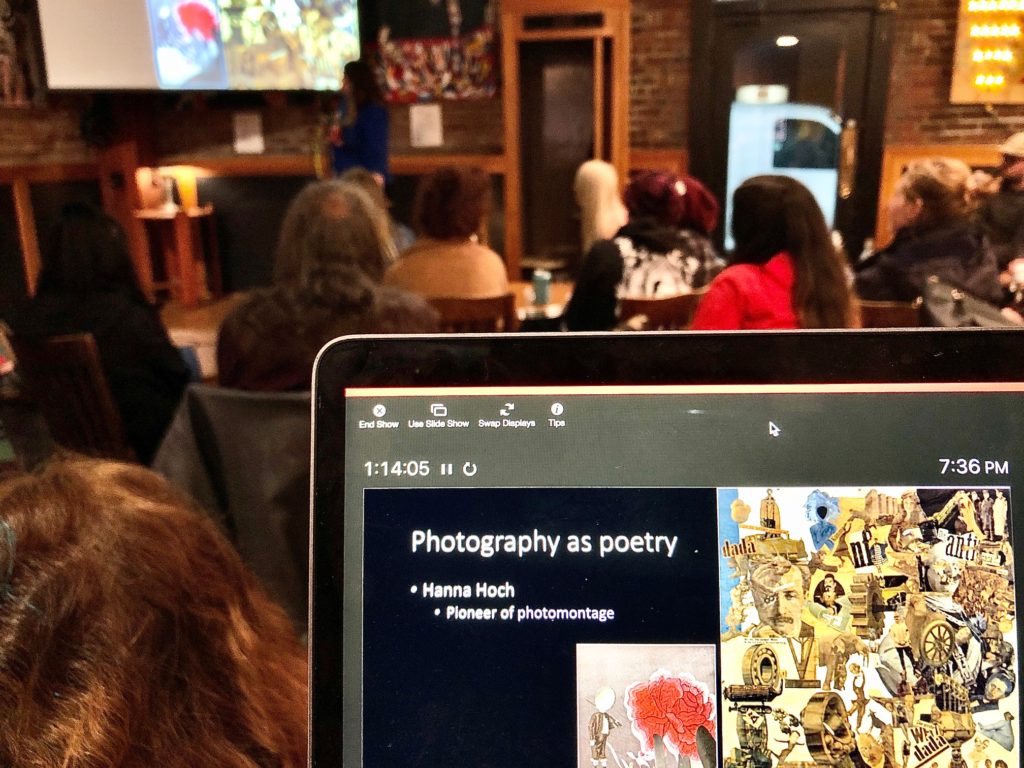

The crowd buzzed in anticipation of the night’s presentation, glasses clinked, murmurs echoed throughout the room, the enthusiasm fully palpable as NW Noggin’s Old Town Talks settled into its new locale at Floyd’s Old Town Coffee...

LEARN MORE: OLD TOWN TALKS: Free Art & Science

After a brief hiatus, this free NW Noggin science-art-fusion community event has returned to the Northwest!

Many thanks to Velo Cult Bike Shop, which hosted us for years, and to Floyd’s Old Town Coffee for picking it up. The return of this series was co-hosted by Kit S. Carlton, a local New/Mixed media artist, and Sydney Boutros, a Behavioral Neuroscience Ph.D. student at OHSU. Joining forces, Kit and Sydney explored the mysterious science underlying memories, while drawing in the essence of poetry and abstract art.

LEARN MORE: Kit Carlton on Instagram

Poetry is memorable

Kit began by explaining the etymology of the word “poetry”—which has its root origins in ancient Greek: ποιεω (poieo) = I create. She explained that in pre-literate societies poetry initially operated as an oral mnemonic device of sorts in order to record/preserve cultural and personal histories, including genealogies, societal laws, and important narratives.

LEARN MORE: Memory decreases for prose, but not for poetry

Some linguistic theorists have posited that early poetic forms originated as songs or epic poems and that poetry differs from common speech in its use of rhyme, rhythm and refrain. These “3-R’s” are known techniques for encoding information for later remembrance!

LEARN MORE: Poetic speech melody: A crucial link between music and language

LEARN MORE: Poetry and Neuroscience: An Interdisciplinary Conversation

Line length in poetry – and genes

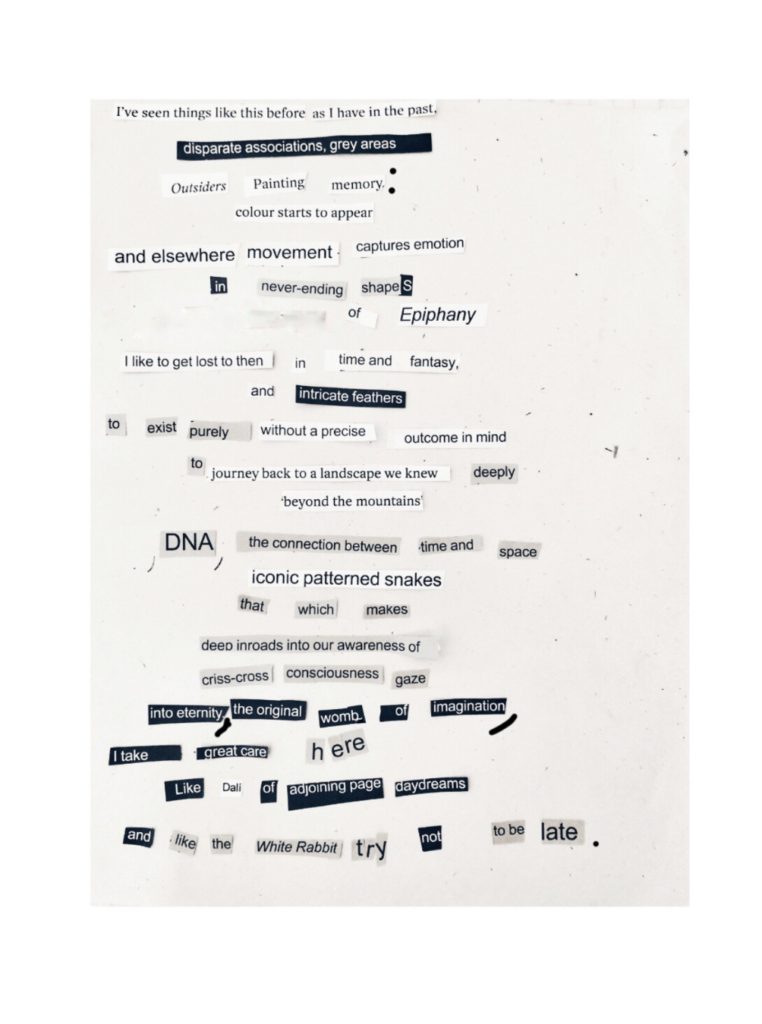

Kit then shifted the discussion to the “anatomy of a poem,” specifically focusing on the elements of lineation which are crucial to the work’s overall organizational structure and constitution. Line length matters.

LEARN MORE: An Anatomy of the Long Poem

LEARN MORE: What Is The Anatomy of a Poem?

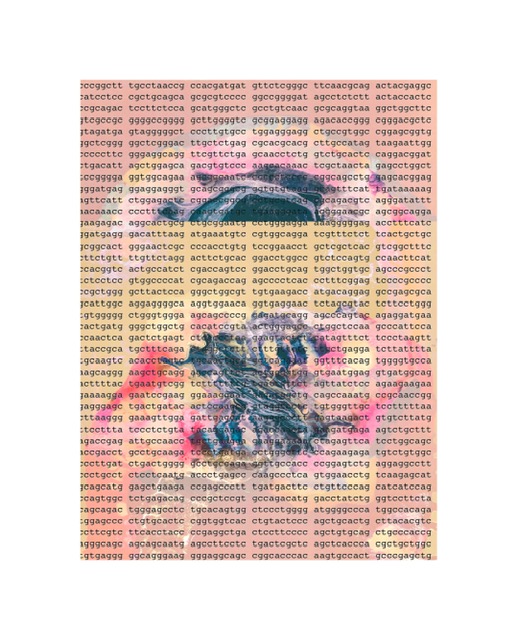

As Kit recounted her visit to the Imaging Facility at OHSU, she expressed how she saw a beautiful metaphor emerge regarding the symmetry of our genetic encoding process and where/how the lines break in a poem, through techniques like enjambment (“the running-over of a sentence or phrase from one poetic line to the next”) or caesura (“a stop or pause in a metrical line”).

LEARN MORE: Lineation – A Guide to the Line Break in Poetry

LEARN MORE: Learning the Poetic Line

“If the mind is wider than the sky, (and it is), the line can be (like a mind) larger than the space that contains it. I love that the making of the lines signal edges both made and found, and that for all of their possibilities in form, they move forward by breaking.”

—Kathleen Peirce

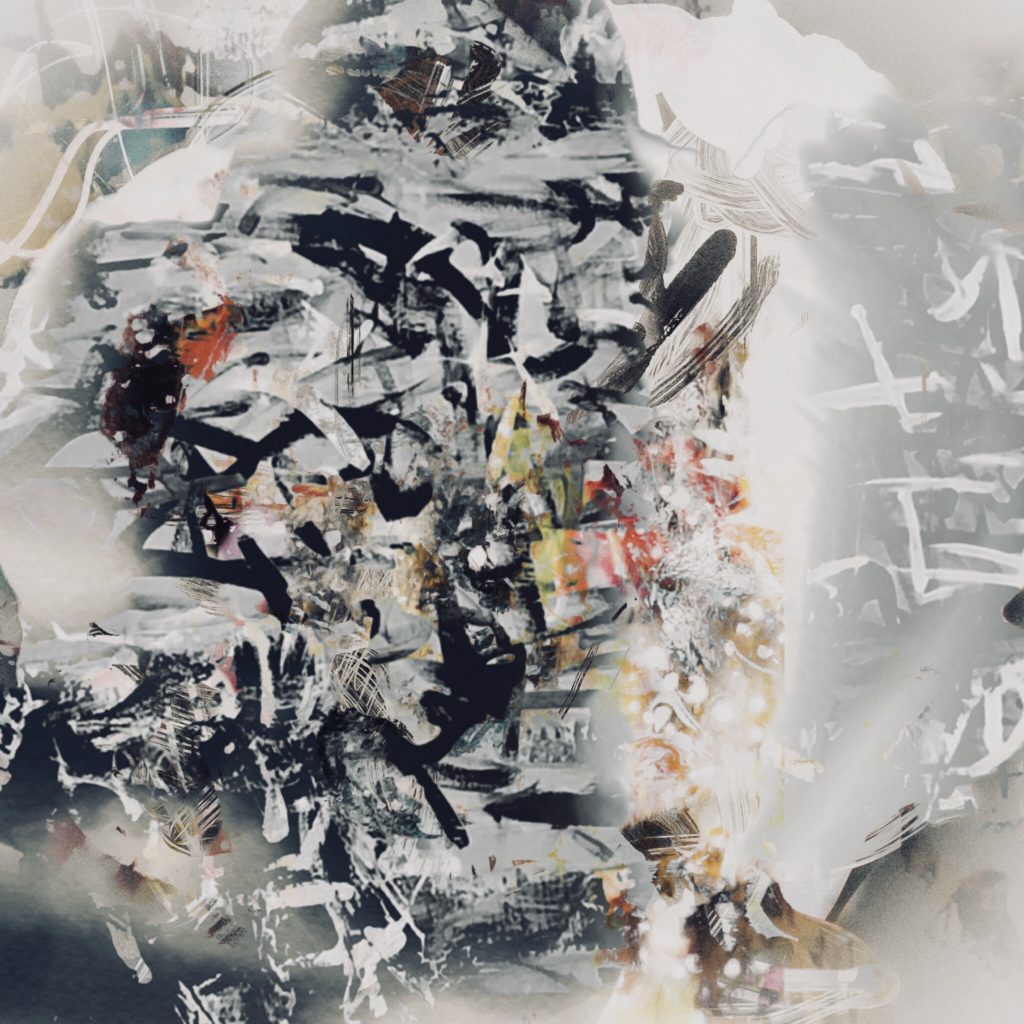

Acrylic, Digital Processing and Photo Transfer 40×40

Kit Carlton

The audience was introduced to two distinct forms of poetry: Ekphrastic and Dadaist. Thanks to Kit, attendees were invited to create their own lines & share them on a common poetry wall…

LEARN MORE: What is Ekphrasis? (Poetry Foundation)

LEARN MORE: What is Dada? (Poetry Foundation)

LEARN MORE: Discover how Dada artists used chance, collaboration, and language as a catalyst for creativity

LEARN MORE: The Starry Night

Poetry is memorable speech

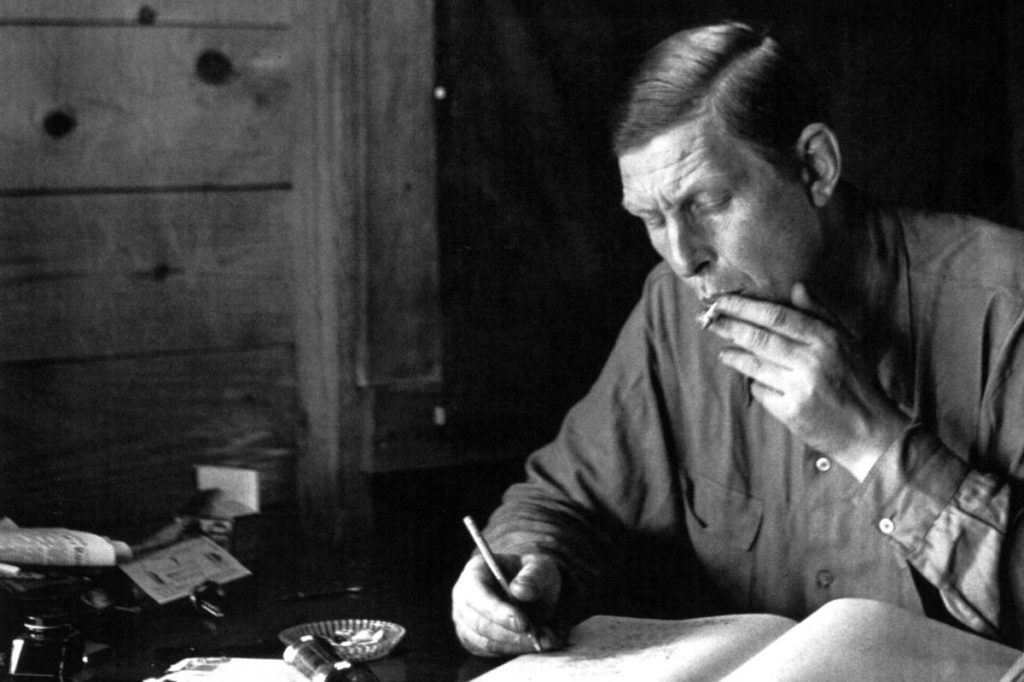

W. H. Auden, one of the most celebrated poets and literary essayists of the 20th century, famously defined poetry as ‘memorable speech’— and he is not alone in his assessment.

Some scholars hypothesize that the aforementioned poetic elements (rhythm, refrain, and also kennings) are essentially literary techniques (e.g., parataxis) which enable a reciter to later recreate the poem from memory.

“Of the many definitions of poetry, the simplest is still the best: ‘memorable speech.'”

—W. H. Auden

LEARN MORE: A master of memorable speech

LEARN MORE: There’s Parataxis, and Then There’s Hypotaxis

LEARN MORE: Memory for Poetry – More than Meaning?

LEARN MORE: The emotional power of poetry: neural circuitry, psychophysiology and compositional principles

“A professor is one who talks in someone else’s sleep.”

—W. H. Auden

What we know about memory

Memory, according to Sydney, is far more complex and dynamic than it might first appear.

There is no one single type of memory, she emphasized. There are multiple categories, which Sydney walked through with the audience at Floyds.

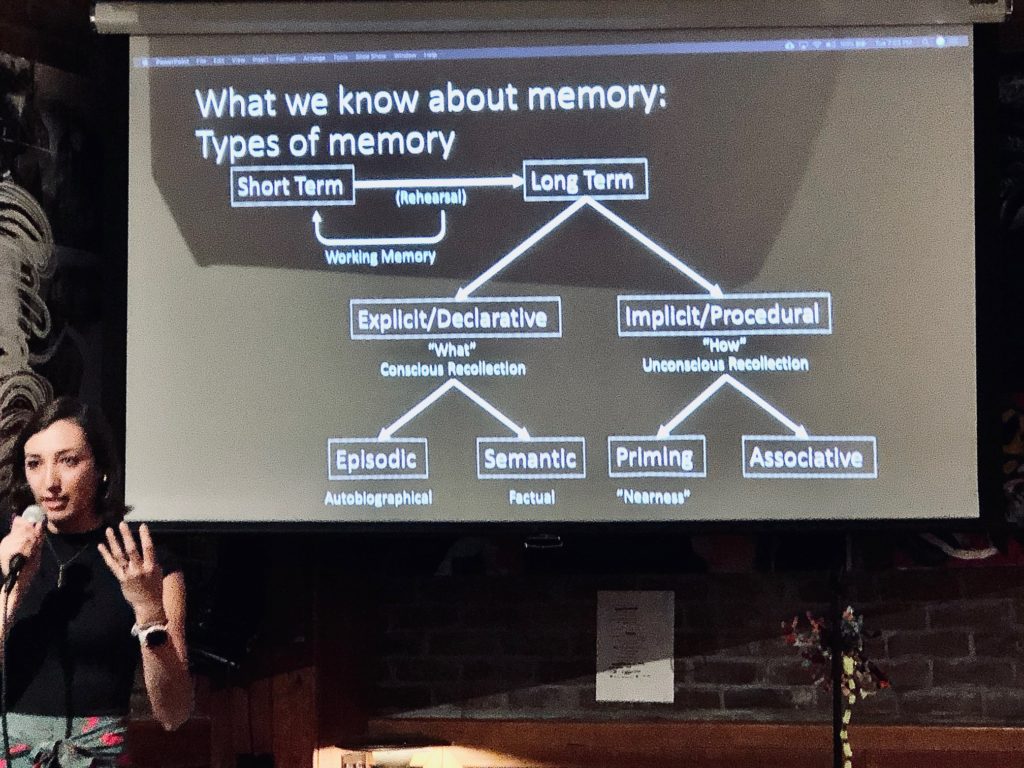

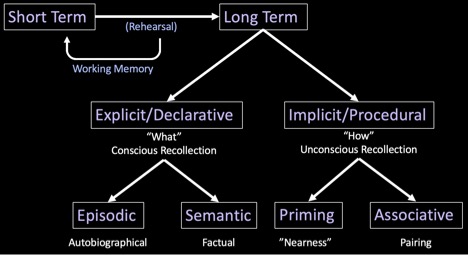

Memory, for example, is divided into “short-term” (STM) and “long-term” (LTM) forms.

Short term is exactly what it sounds like – it’s SHORT. How short? Typically less than 30 seconds! Short term memory also has a limited capacity. People can hold about 7 things in their short-term memory (and perhaps fewer), give or take a couple. Sydney shared a short poem to illustrate the natural connection between poetry and short-term memory…

Our DNA: A Haiku

—Sydney Boutros

I remember you

Broken for all to observe

Fixed again, hiding

Haikus are a good way to grasp the way poetry unwittingly uses our ability to temporarily store information – three lines of 5/7/5 syllables, or about our maximum short-term capacity. Sydney then decided to change her poetry, challenging the audience to update their memory!

Our DNA: A Haiku

—Sydney BoutrosI remember youBroken for all to observe

Fixed again, hiding

You come out to play once more

Reconsolidate

This updating of information, she explained, is called working memory.

LEARN MORE: About the Distinction between Working Memory and Short-Term Memory

Clearly information does not stay in this limited-capacity, limited-time state. Through rehearsal, short-term memories may ultimately become long-term memories. Repetition! Repetition! Repetition! Long-term memory is thought to have unlimited capacity and unlimited duration. Here, we can become even more specific about different types of memory.

LEARN MORE: What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory?

LEARN MORE: Regular Rehearsal Helps in Consolidation of Long Term Memory

Sydney explained how long-term memory branches out quickly into two broad categories: Explicit (or Declarative), and Implicit (or Procedural). Think of explicit as those things you consciously bring forward, and implicit as those that you never think about, but just know. Another way to put it is that explicit memory is the “what,” and implicit memory is the “how.”

LEARN MORE: Brain Systems Underlying Declarative and Procedural Memories

LEARN MORE: Conscious and Unconscious Memory Systems

Diving deeper into these sub-divisions, explicit memory can be further divided into “episodic” and “semantic,” which are very fluid categories that often intermingle. For example, think of the terror attacks on 9/11. If you were alive and aware at that time, you can probably picture exactly where you were and what you were doing. This is an episodic memory. You also probably know some facts about 9/11, like date, location, time – and these pieces are semantic memories.

LEARN MORE: Interdependence of episodic and semantic memory: Evidence from neuropsychology

LEARN MORE: The Episodic Memory System: Neurocircuitry and Disorders

On the unconscious side of things, implicit memory can also be broken down further into “priming” and “associative” memory.

Dr. Ivan Pavlov was a key player in the study of associative memory: he rang a bell every time he fed his dogs. He realized soon that the dogs began to pair (or associate) the bell with getting fed, and would salivate whenever the bell rang – this is textbook associative learning!

Priming is also unconscious.

For example, if I ask you to fill in these words:

Po____

Br________

Me_____

Ab_________

You may recall words like “poetry,” “broken” (or “brains” :), “memory,” “abstract.” You could have filled in “pork,” “breakfast,” “mean,” “absolutely,” or many, many other words! But since you have been reading about the first set of words throughout this post, they were “nearer” in your mind, and so you recalled them quicker. Tricky!!

LEARN MORE: Priming and the Brain

LEARN MORE: The neuroscience of mammalian associative learning

LEARN MORE: Memory processes in classical conditioning

LEARN MORE: Associative memory cells and their working principle in the brain

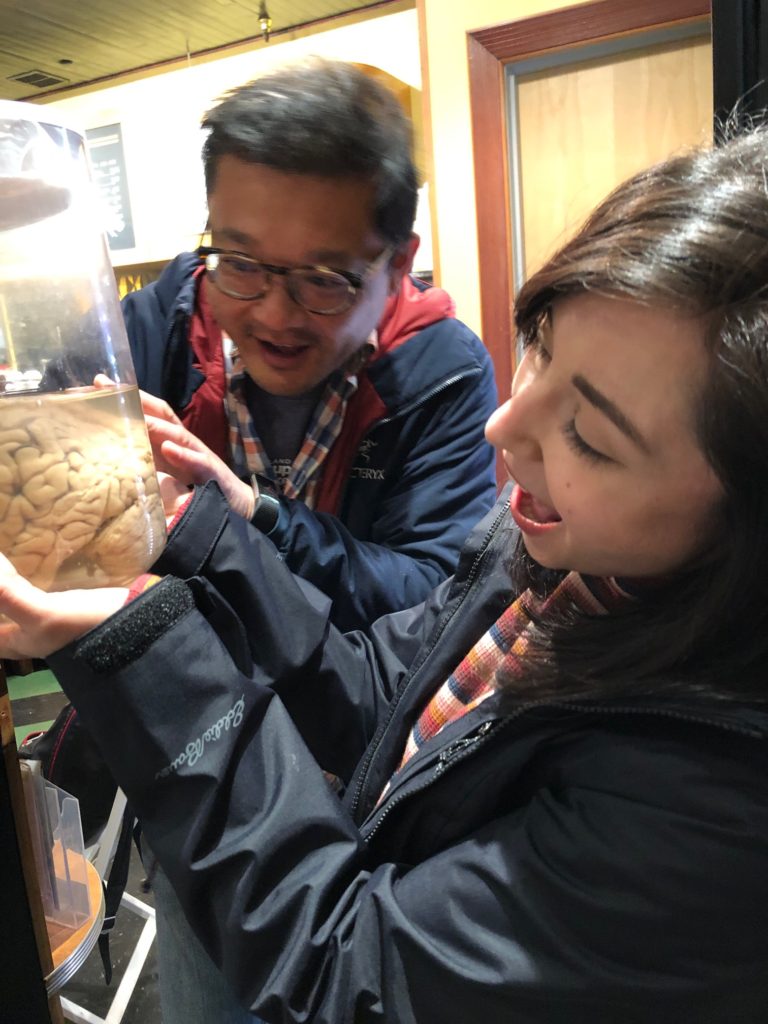

The (Brief) Neuroanatomy of Memory

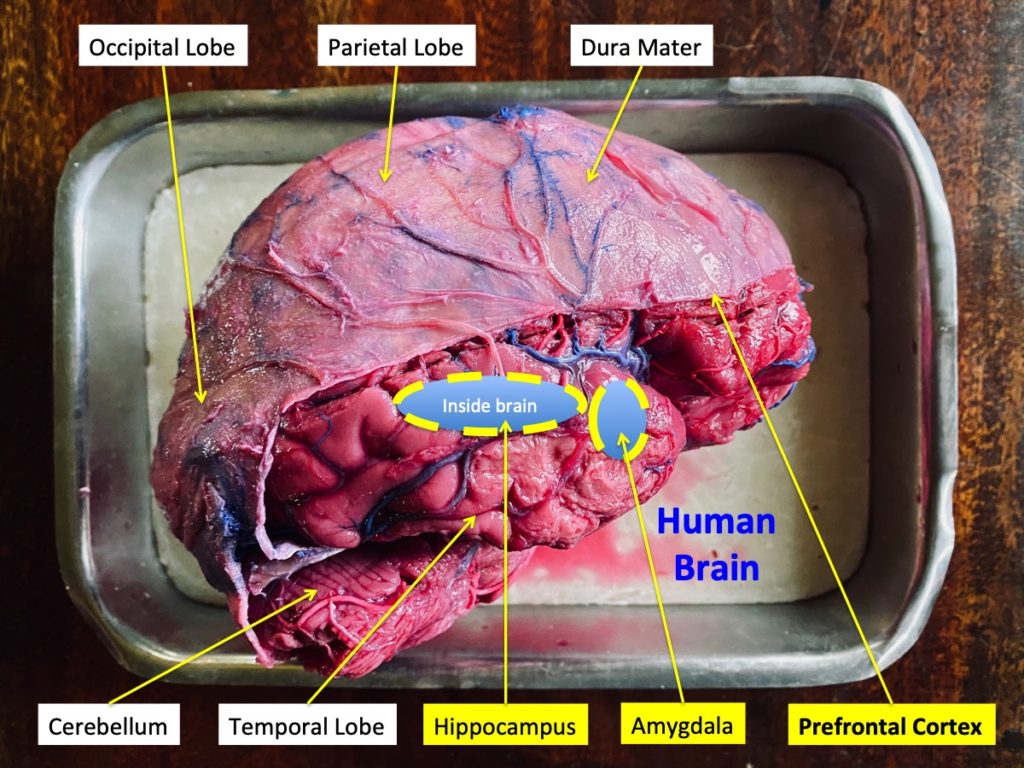

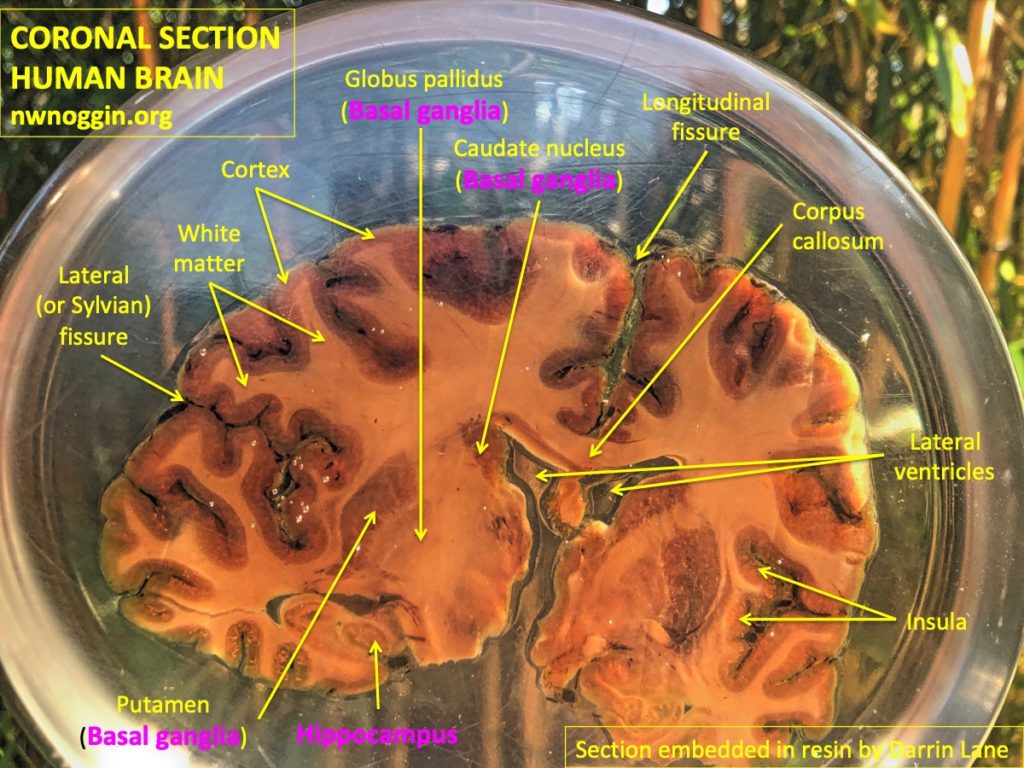

Once Sydney walked everyone through these different types of memory, she also touched on some of the important parts of the brain that we know are involved.

- Prefrontal Cortex: a major contributor to memory (particularly working memory). You wouldn’t be you without your PFC! It is especially important for modulating and updating information.

- Basal Ganglia: several interconnected subcortical brain regions (structures deep below the cortex, or wrinkled outer “bark” of the brain) that are critical for implicit, procedural memory, like riding a bike (don’t forget to wear your helmet!).

- Amygdala: sometimes called the “fear center” of our brain. This almond-shaped subcortical nucleus in our temporal lobe is important for emotional and associative memories.

- Hippocampus: A BIG PLAYER – and essential for developing our long-term, explicit memories.

LEARN MORE: Memory & Learning with Noggin @ PAM

LEARN MORE: The Role of Prefrontal Cortex in Working Memory: A Mini Review

LEARN MORE: The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala

LEARN MORE: The Physiology of Fear: Reconceptualizing the Role of the Central Amygdala in Fear Learning

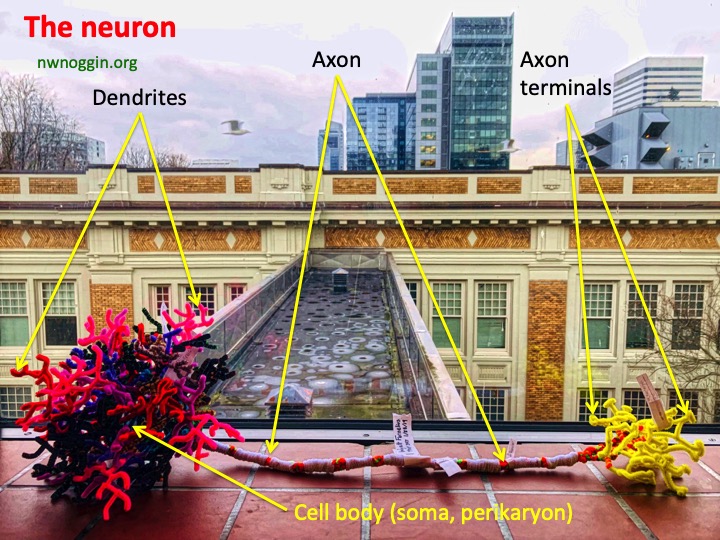

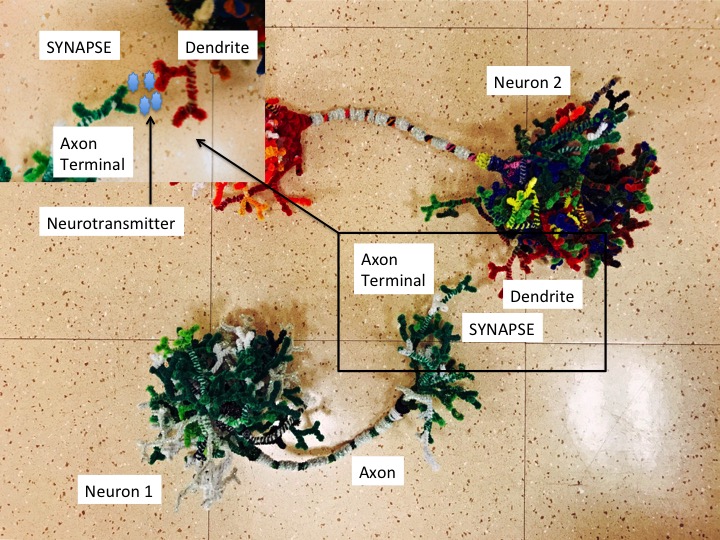

Diving down farther, Sydney described the building blocks of the brain: neurons (though of course don’t forget the glia!). Neurons make up a lot of the big, pink organ in our heads, and are incredibly dynamic. They communicate in so many ways, constantly growing and trimming connections with each other, sending information with millisecond precision.

Synapses matter

The classic neuroscience mantra has been “cells that fire together, wire together.” In other words, neurons that talk to each other a lot will grow strong, efficient connections, while those that don’t will quit trying and retract their communication lines.

But genes matter too

“I’m a recovered synapto-holic.”

—David Glanzman, UCLA

Much of the learning and memory field has focused on synapses: how chemicals from one neuron span this tiny gap and provoke responses and changes in the next. The complexities here are amazing, but we haven’t been able to describe everything about the process of encoding a memory.

And synapses become efficient because of proteins, the construction crews of the body. And proteins, of course, are built from instructions in our DNA – the master architect. DNA lives in the nucleus of the neuron, meaning if we really want to understand memory, we need to start looking there.

This is where we truly delve into the unknown.

Historically, DNA has been perceived as unchangeable. We inherited it from our parents, who received it from theirs, and we pass it on to our offspring. It IS us!

Recent evidence doesn’t dispute this, but highlights how the expression of genes does change. DNA sends blueprints to RNA (think of them like contractors), who then send them to proteins (the construction crew).

LEARN MORE: Central Dogma of Biology

LEARN MORE: 60 years ago, Francis Crick changed the logic of biology

LEARN MORE: Central Dogma of Molecular Biology

Yet which particular RNA blueprints or how many copies our DNA sends (or transcribes) WILL change based on our life experiences, changing which proteins get built (or translated).

You may have heard of “epigenetics” – this is how our own life experiences can change our gene expression, and our brains.

Life experiences – like forming new memories!

LEARN MORE: What Do You Mean, “Epigenetic”?

LEARN MORE: Epigenetics across the human lifespan

LEARN MORE: Carry on my wayward son

Breaking DNA to form memories

A new hypothesis that has “broken” into the field is that DNA may quite literally break in order to form some new memories. These breaks (called double strand breaks, or DSB’s) are seen (in mice!) after exploring new places that are later recalled, and they facilitate different gene expression, based on where and when they occur.

DSB’s are implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases, yet they may also be critical for learning and memory.

“That which does not kill us, makes us stronger.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche

LEARN MORE: Physiological Roles of DNA Double-Strand Breaks

LEARN MORE: Activity-Induced DNA Breaks Govern the Expression of Neuronal Early-Response Genes

LEARN MORE: Physiological Brain Activity Causes DNA Double Strand Breaks in Neurons — Exacerbation by Amyloid-β

LEARN MORE: Early neuronal accumulation of DNA double strand breaks in Alzheimer’s disease

This hypothesis is what Sydney is working on as a graduate student in Behavioral Neuroscience – so please stay tuned!

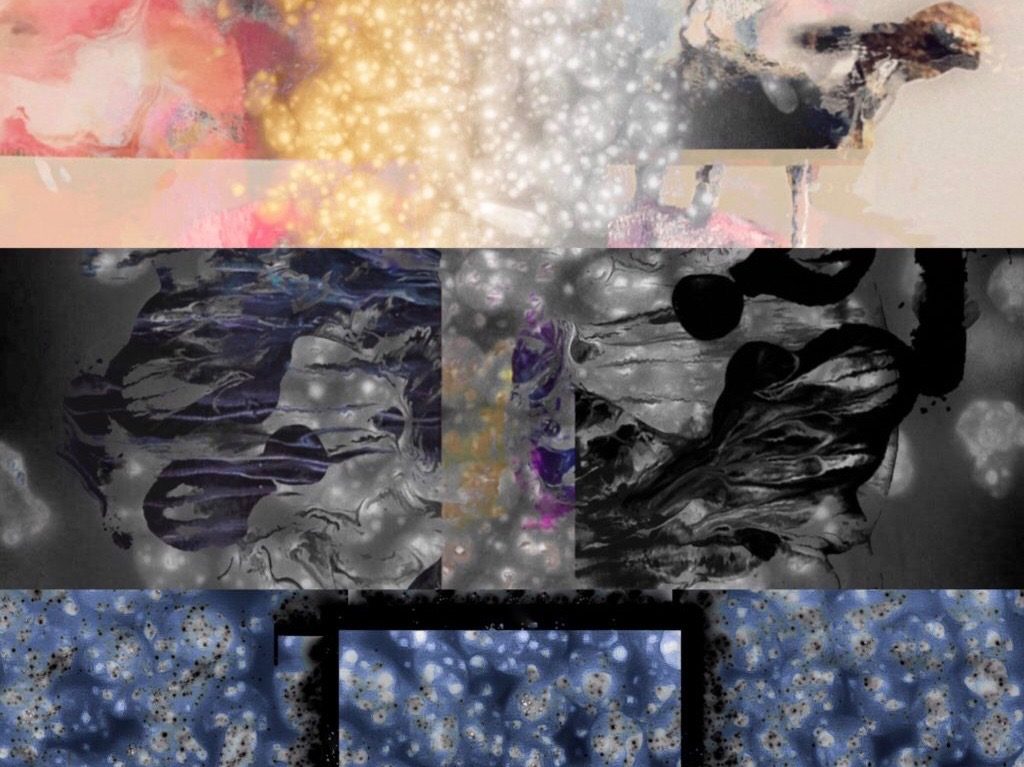

Acrylic, Graphite, Magazine Clippings, Digital processing and Photo Transfer on Wood Panel, 48×48, Kit Carlton

“What one must paint is the image of resemblance — if thought is to become visible in the world.”

—Rene Magritte

Kit connected this developing scientific concept to aspects of abstract art.

She described how painters and poets also structure language, and break lines, and explore and experiment to affect our experience and memory. Language itself is an abstraction, with words and phrases signifying concepts and ideas drawn from multiple life experiences.

And Art, Kit emphasized, is also a form of language!

“Figurative language uses figures—that is, images, ‘pictures’ of things—to provide clarification and intensity of thought. For grace, for illumination, for comparison, to create a language that is vibrant not only with ideas but also with the things of the world that we know through our sense experiences”

—Mary Oliver

LEARN MORE: Poets and Painters

LEARN MORE: Language is more abstract than you think, or, why aren’t languages more iconic?

LEARN MORE: Why I Am Not a Painter

Sydney’s process

It’s sometimes easy to see how art and science intersect. Science is often achingly beautiful.

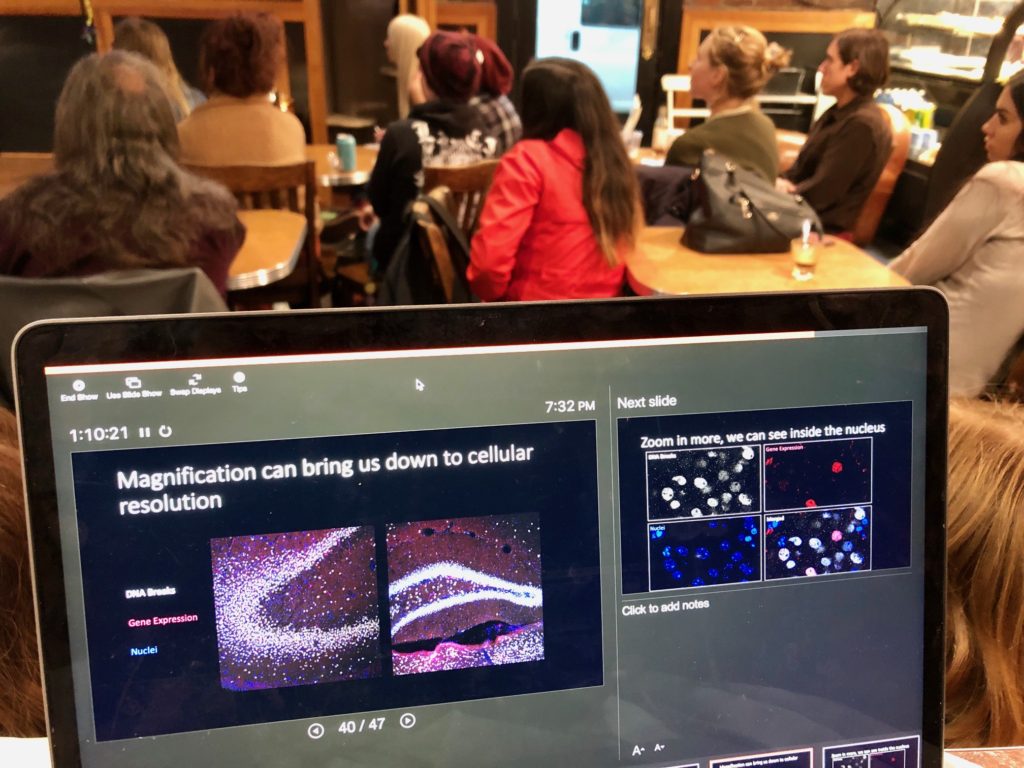

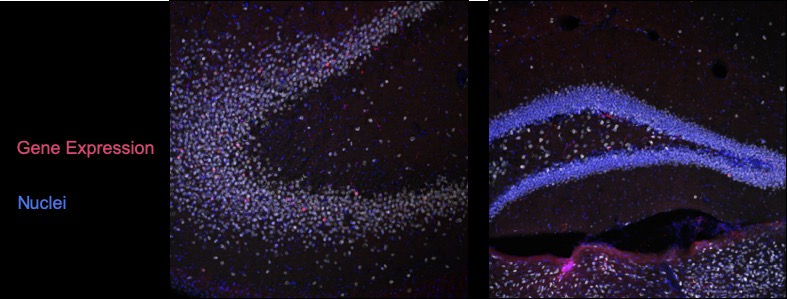

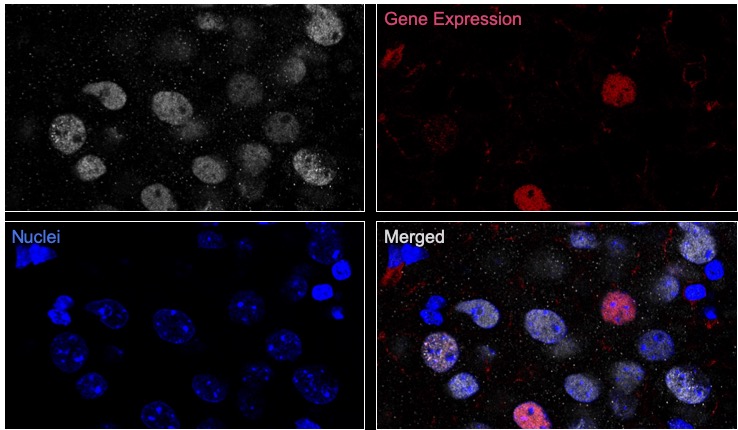

A common technique used by neuroscientists to visualize microscopic pieces of the brain is called immunohistochemistry. We ask questions about small things, so we need ways to AMPLIFY the signals in order to actually visualize them – immunohistochemistry is one way to do that.

Going back to Latin, we can see what this approach entails: “immuno” (use of antibodies) + “histo” (tissue) + “chemistry” (reactions) – using antibodies on tissue to cause reactions and make small signals visible and BIG!

A previous OHSU intern of Sydney’s (named Sydney Nagy – same first name, though not on purpose!) made this great video to describe the details of immunohistochemistry…

LEARN MORE: Immunohistochemistry as an Important Tool in Biomarkers Detection and Clinical Practice

LEARN MORE: Applications of immunohistochemistry

In short, this leads to beautiful, colorful images of brains!

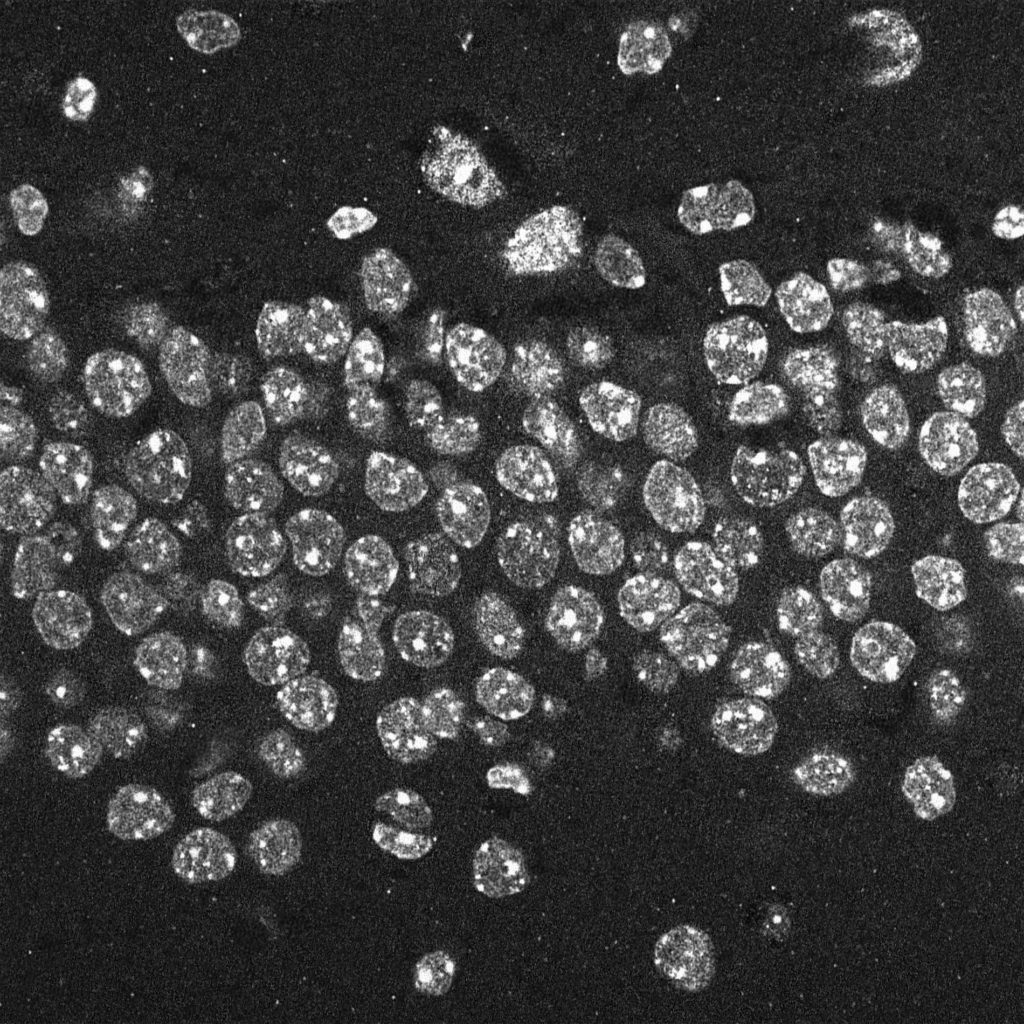

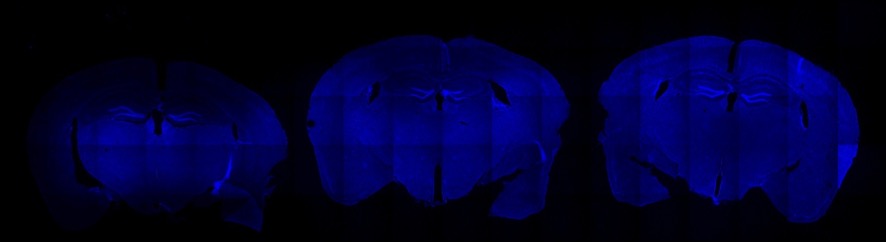

Sydney described her results for normal hippocampal neurons (shown in blue), DNA breaks (white), and gene expression (red). We can look first at low magnifications (4x the normal eye)…

And then zoom in closer to 10x magnification…

And, finally, up to 63x magnification!

Kit integrated these memory-related neural images into several compelling works that hung in Old Town Portland at Floyds.

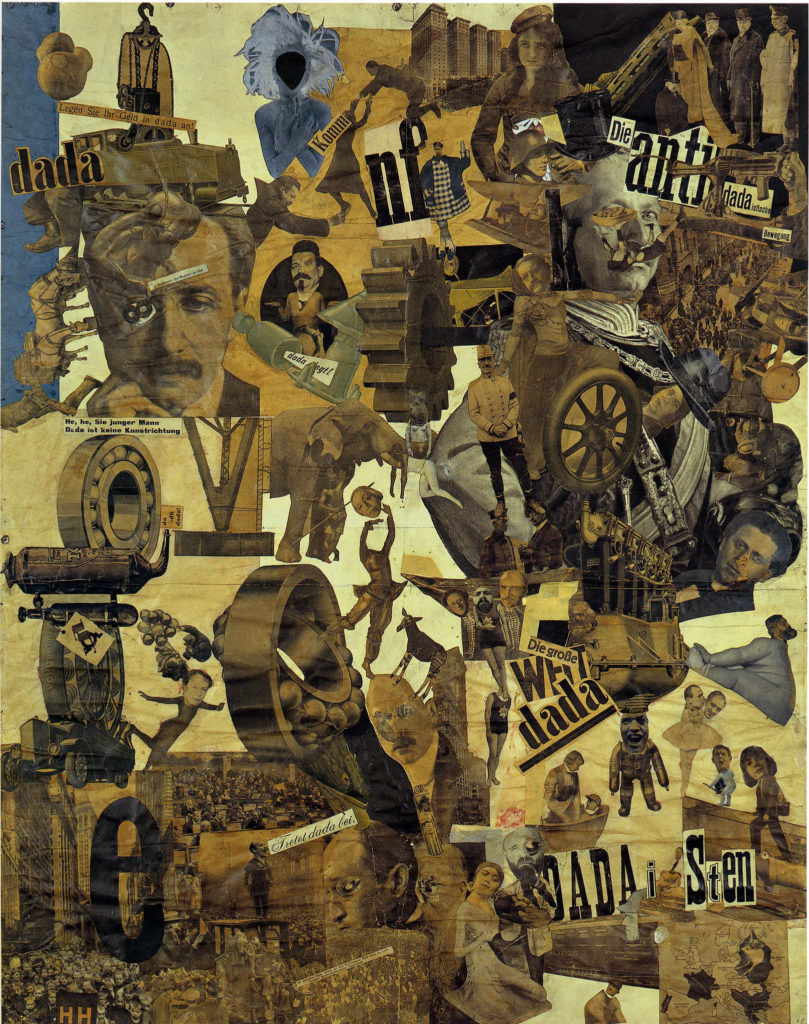

Kit also spoke about how Hannah Höch, a Berlin Group Dadaist who pioneered the photomontage technique, was integral to understanding her own artistic process and what she sometimes refers to as her digital montages.

LEARN MORE: Hannah Höch

LEARN MORE: Hannah Höch: art’s original punk

“…let us think about this new organic system—a pure result of the limpid mechanical process, irretrievable outside a clear photographic creation…in addition to the implacable rigor to which photographic data subject our mind, they are always and ESSENTIALLY THE SUREST VEHICLE OF POETRY”

—Salvador Dalí

At the end of the night the brains in the crowd buzzed with new ideas, abstractions and a charge to ‘Remember’ from our Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo.

Remember you are all people and all people

are you.

Remember you are this universe and this

universe is you.

Remember all is in motion, is growing, is you.

Remember language comes from this.

Remember the dance language is, that life is.

Remember.

—Joy Harjo

READ THE POEM: Remember by U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo

So many thanks are due Nicole Tignor, the owner of the incomparable and welcoming Floyds Old Town Coffee! And sincere thanks to our creative collaborators at the Portland Alcohol Research Center (PARC) at OHSU for generously purchasing art supplies for this event!

Editing and (most) photos by Bill Griesar