Post by Drew Sinclair, undergraduate student veteran at Portland State University and NW Noggin outreach volunteer

Brains use energy

Our brains require a lot of energy. Navigating, remembering, making decisions, responding to circumstances requires the coordinated activity of networks of linked brain regions, and the burning of sugar (glucose) to keep us engaged. Every effort of attention utilizes existing metabolic resources.

LEARN MORE: Brain Energy and Oxygen Metabolism

LEARN MORE: Cognitive cost as dynamic allocation of energetic resources

LEARN MORE: Mental Work Requires Physical Energy: Self-Control Is Neither Exception nor Exceptional

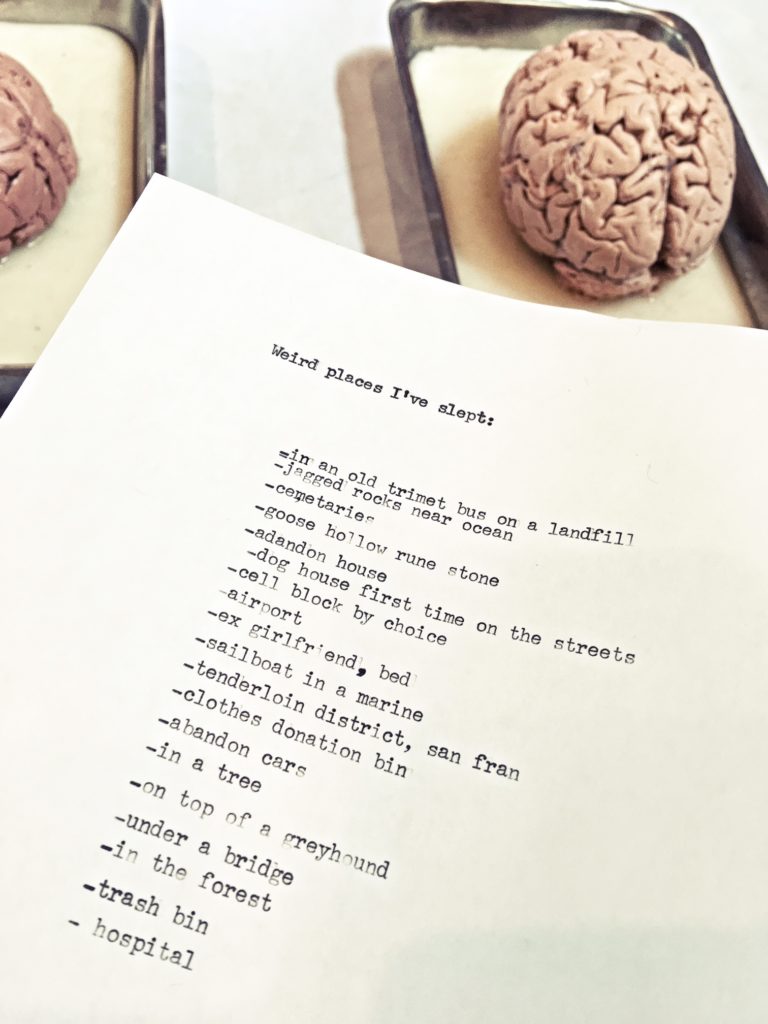

Those without housing work hard

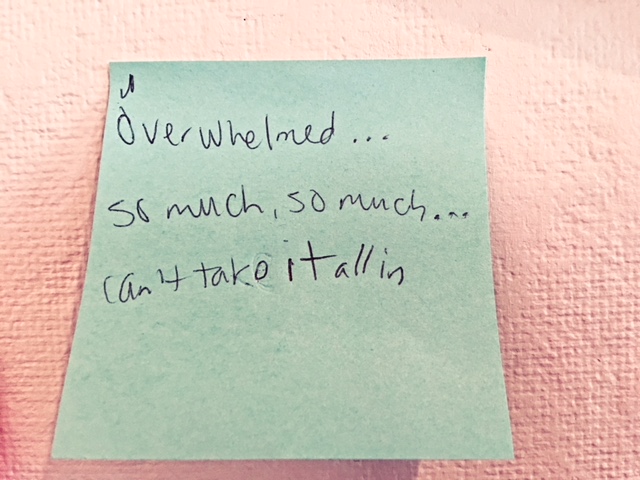

During outreach mornings at p:ear, a homeless youth center, I’ve had impactful conversations with young people coping with addiction, anxiety, depression, abandonment, bias – and often a sense that many, if not most people just pass them by, without notice, as if they somehow weren’t valuable human members of our own community.

LEARN MORE: Noggin @ p:ear

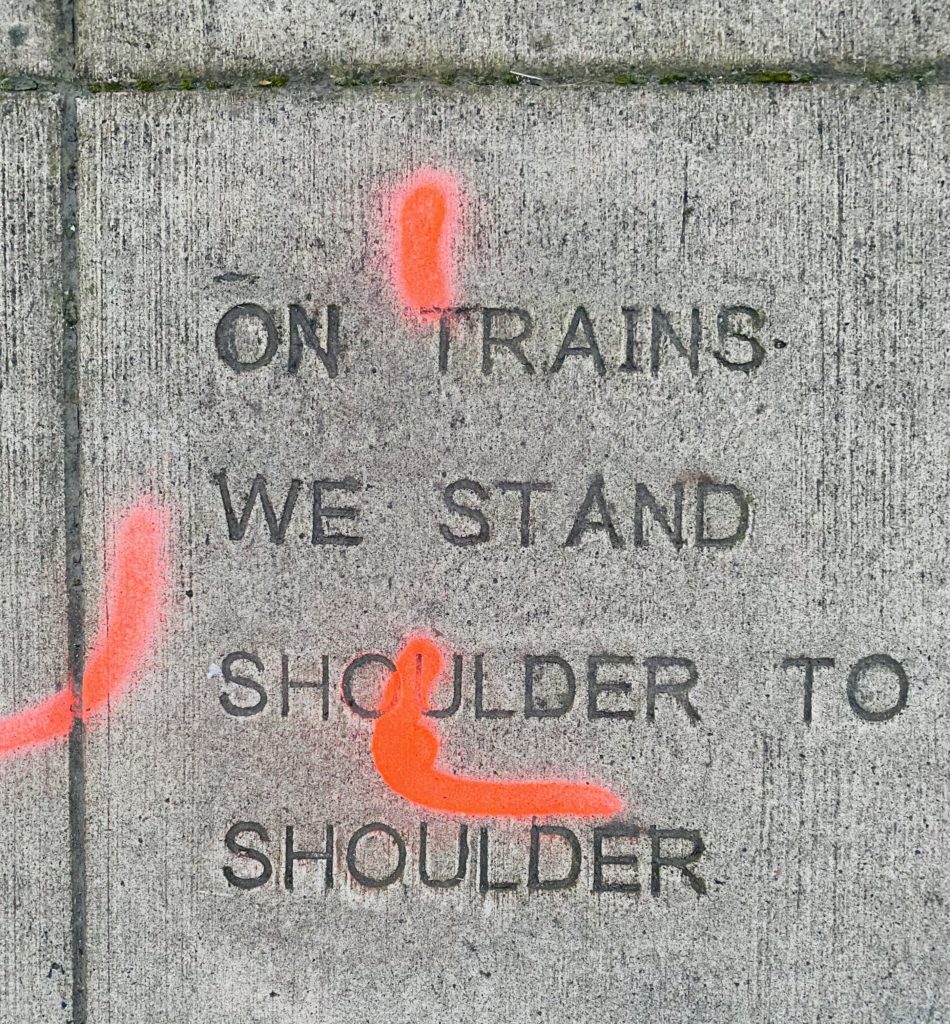

And when your environment demands survival it is unlikely that much attention will be paid to the less threatening details. One less compelling detail for individuals without housing – whose daily stress level is that of someone trying to survive – is navigating the minutia of TriMet’s HOP fastpass.

LEARN MORE: Health Problems of Homeless People

LEARN MORE: Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: A review of the literature

LEARN MORE: Traumatic stressor exposure and post-traumatic symptoms in homeless veterans

LEARN MORE: Capacity for Survival: Exploring Strengths of Homeless Street Youth

LEARN MORE: Trauma Among Unaccompanied Homeless Youth

LEARN MORE: Tackling Health Disparities for People Who Are Homeless? Start with Social Determinants

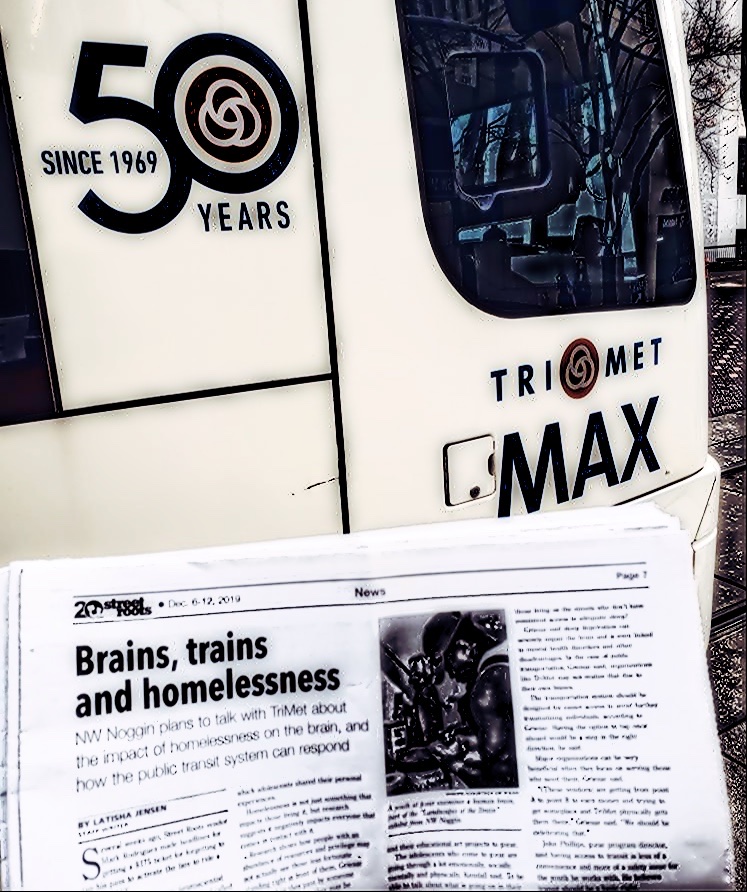

This issue recently hit public consciousness after TriMet security issued a $175 fine for a Street Roots vendor who had acquired an ‘Honored Citizen’ HOP card. He pre-loaded it with $28 (what he needed to spend for unlimited rides for a month) but forgot to ‘tap’ his card before boarding a MAX train.

LEARN MORE: Brains, trains and homelessness: How public transit can respond to neuroscience

LEARN MORE: A Homeless Street Roots Vendor Was Fined $175 by TriMet For Not Tapping His Hop Card When He Boarded the MAX

HOPcards are complex

TriMet’s new fare system requires passengers to ‘pre-load’ money on a HOP card and then ‘tap’ their card before riding any bus or streetcar (where the tap recorder is found on board) or a MAX light rail (where the recorder is somewhere along the platform). Tapping withdraws money for a fare, and that fare is, according to Tri-Met, good for 2.5 hours of transit.

TriMet spokesperson Tia York described the HOP card as “like a gift card.” After spending a set amount of money (for an Honored Citizen that’s $28), the rest of that month’s rides are free. Neglecting to tap for each and every ride, however, may result in a fine – although specific information on fines is not easily accessible on the TriMet website (the announcement of the specific policy is buried in their website under ‘News’).

LEARN MORE: TriMet Board of Directors approves fare evasion penalty changes

Punishment isn’t effective

“A serious issue with negative punishment is that while it might reduce the unwanted behavior, it doesn’t provide information or instruction on more appropriate responses.”

–Kendra Cherry

Do fines effectively promote payment for rides?

Psychologists sometimes refer to a fine as ‘negative punishment.’ ‘Punishment‘ aims to decrease unwanted behavior (like forgetting to tap a Hopcard before boarding the MAX), while ‘negative‘ means the taking away of something valuable (in this case $175, because of the fine).

However not everyone is in a position to receive or respond to TriMet’s attempts at punishment in the same way.

LEARN MORE: Behavior Modification

In the case of a forgotten ‘tap,’ the implied appropriate reaction to the fine is to pay more attention and tap your HOP card in the future before you get on the MAX. The problem, though, is that expecting more attention from those without a safe place to sleep is not reasonable.

Many people in our community face significant trauma, sleeplessness, stress, poor nutrition, and the elements. If we faced similar circumstances, we’d forget to ‘tap’ on occasion; in fact, I’ve forgotten to tap even after a good night’s sleep!

Neurophysiologically, it wouldn’t be entirely inaccurate to claim that asking someone experiencing chronic homelessness to be even more vigilant is like asking someone in a combat environment to stop and flip a coin every time they get in their humvee. And the coin is actually like a gift card. And you’ve never used a gift card because you’ve been on the fringes of society for many years. And sometimes you run out of coins but you can’t tell because you don’t have a smartphone to check your gift card balance.

It really can be this confusing for someone in that situation. Having the “curse of knowledge” – understanding how things work merely because we’ve experienced them – gives us an incorrect sense that we understand what it’s like for people in different situations. It isn’t impossible to adapt to these requirements, but it takes time and positive social, environmental, and behavioral reinforcement. Punishment is not the answer.

Is there bias in enforcement?

“We all have cultural bias, racial bias. One of the difficult things around this subject is to deny that we have places we go to subconsciously, and unless you consciously decide that that’s wrong and you’ve got to do something about it, especially if you’re in a position of power, it won’t change.”

– David Oyelowo

And what about bias in fare enforcement?

We all exhibit bias – it’s how our brains cope with an overwhelming amount of information. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky first described the ‘representativeness heuristic’ – a shortcut for making quick judgments based on mental prototypes. For example, we might jump to conclusions about what a typical “fare evader” looks like, or how they’ll behave. Certain individuals could be targeted based on their physical appearance, or body language.

LEARN MORE: NIH on Implicit Bias

LEARN MORE: Subjective Probability: A Judgment of Representativeness

LEARN MORE: The development of the representativeness heuristic in young children

LEARN MORE: Psychologist wins Nobel Prize – Daniel Kahneman is honored for bridging economics and psychology

LEARN MORE: Race, Bias & Brain: You Can’t Control Art

LEARN MORE: Listening to testimony @ p:ear

TriMet’s response to accusations of bias is a study published in 2016 titled, “Analysis of Racial/Ethnic Disparity in TriMet Fare Enforcement Outcomes on the MAX 2014-2016.”

LEARN MORE: Analysis of Racial/Ethnic Disparity in TriMet Fare Enforcement Outcomes on the MAX 2014-‐‑2016

From the study: “Differences between the fare evasion survey results and enforcement outcomes are small and indicate little disparity. Thus, it does not appear TriMet fare enforcement on the MAX is systemically biased towards certain races and ethnicities, however the elevated percentage of African American riders being excluded should be examined more closely.”

LEARN MORE: Study: Black MAX riders more likely to be banned from TriMet for fare evasion

But how was this study done?

The author, Brian C. Renauer of the Criminal Justice Policy Institute at Portland State University, compared two surveys commissioned by TriMet to examine whether there was “systemic racial bias.”

For the “Ridership Survey,” “Surveyors approached transit riders and asked them to voluntarily fill out a 24 question survey,” including questions on race. The distribution of those who chose to respond was compared with results from a second “Fare Evasion Survey.” “Contractors hired by TriMet shadow inspection personnel and note the number of passengers with valid fares, no fares or invalid fares. The perceived race/ethnicity of persons with no fares or invalid fares is recorded by the contractor.”

But not everyone answered the Ridership survey. Cultural factors, language differences, a perceived threat from official TriMet contractors, unfamiliarity and/or distrust may have selectively impacted participation and skewed the results. Second, in the Fare Evasion survey, “unknown” was chosen for race about 2,000 times (6.4%) in those without valid fares.

LEARN MORE: Survey Nonresponse

LEARN MORE: Indirect Estimation of Race/Ethnicity for Survey Respondents Who Do Not Report Race/Ethnicity

And this study says absolutely nothing about bias against those who lack access to safe, secure housing – of any race.

Lasana Harris and Susan Fiske found that people respond harshly to in “extreme outgroups,” including people without homes, perceiving them as less “warm” and “competent” than others. They “…elicit disgust, an emotion that is not exclusively social, being directed both at people and objects that seem repellant.” In addition, networks in frontal lobe areas (including medial prefrontal cortex), which are essential for social cognition and for responding to others as human beings with relatable hopes, thoughts, dreams, lives – respond less to images of those who lack housing.

LEARN MORE: Landscapes of the Brain: Seeing us all through research & art

TriMet also revealed evidence of their own bias in a tweet…

A public records request by Oregon Public Broadcasting found an underwhelming 8 complaints during a period in which the transit agency accommodated 16 million trips!

From OPB: “Nearly all of the grievances TriMet documented had the same issue with lax fare enforcement: the alleged abuse of public transit by people experiencing homelessness.”

At the end of the TriMet study, three principles are outlined that have received little recognition in the discussion about possible biases in fare enforcement that are equally relevant to those who are homeless. The last two lines of the study are: “Given the results of this report, the third principle is particularly important. The possibility for bias is real and efforts to ensure practices in enforcement are fair for all should continue.”

And what is the “third principle?”

“Principle 3: Even if the results are not indicative of a pattern of systemic bias it does not mean a transit agency should be any less vigilant in ensuring its enforcement practices are fair and un-biased through continued training, data monitoring, and policy reflection.”

If only to highlight the need for scientific best practices, this advice should be considered as TriMet continues to reference a single, un-replicated 2016 study about racial bias for proof of a more thoroughly unbiased system.

Fines are traumatic

Demanding $175 from someone without resources is an enormously threatening experience. It can induce a stress response that can’t be easily mitigated. If honored citizens pay less, why aren’t they fined less? If one has qualified for that status, then why doesn’t it remain consistent in both fares and fines? If TriMET wants to alleviate the financial burden by offering a lower-tier fare bracket, then why aren’t there lower-tier fines?

In the case of fines that are impossible to pay, “free-riding” can seem like the only reasonable choice. This casts people further out of “normative” society and gives them more reason to distrust the system and seek simply to avoid it altogether. Personally, I’ve witnessed individuals who keep watch out the train window for TriMet officers, and hurriedly get off the train before the officers board to check tickets and fares. This is essentially adding another reason for these individuals to watch their backs, as if they already didn’t have enough.

LEARN MORE: Feeling stressed?

LEARN MORE: Effects of Acute Stress on Decision Making

LEARN MORE: Decision-making under stress: the importance of cortico-limbic circuits

Furthermore, these programs are newly in place for TriMet, and not everyone is familiar with practices that are standard in more privileged communities (e.g., swiping or tapping a card). And there are also changes that occur with age. “Increasingly, human factors and ergonomics specialists have argued that attention needs to be paid to age-related changes in basic human abilities, to ensure that the demands made by the technology fit the capabilities of the user.”

LEARN MORE: Aging and Information Technology Use: Potential and Barriers

In our Street Roots vendor case, “tapping” might seem simple, but “tapping” when one is already burdened by the crippling stress and anxieties of homelessness is very easy to forget.

Reward works better

“…that their merely being there

–John Ashbery

Means something;…”

Offering rewards can be a more compelling behavior management technique. TriMet does an extraordinary job moving people around the region, providing essential access to services and employment. This Street Roots vendor was trying to reach his job, and he’d put $28 on his card in anticipation of a full month of rides. That should be celebrated!

Why not offer more incentives for tapping, instead of punishment for forgetting to do so? Since the MAX is where most fare evasion occurs, why hasn’t TriMet added tap recorders to the trains? And why are those without housing or other resources, who suffer from the consequences of trauma, bias and lack of sleep, fined at all for a missing tap – or for the ride itself?

“…that soon

–John Ashbery

We may touch, love, explain.”

LEARN MORE: Opposing effects of reward and punishment on human vigor

LEARN MORE: Differential modulation of cognitive control networks by monetary reward and punishment

LEARN MORE: Traveling Towards Disease: Transportation Barriers to Health Care Access

LEARN MORE: Why Decriminalize Fare Evasion?

LEARN MORE: Washington Will Decriminalize Fare Evasion. Better Idea: Free Transit

LEARN MORE: Kansas City becomes first major U.S. city to make public transit free

LEARN MORE: Free Public Transit: And Why We Don’t Pay to Ride Elevators

LEARN MORE: The Case for Leaving Fare Beaters Alone and Making Public Transit Free

This is clearly a nuanced topic of discussion, but one that needs better solutions based in research, evidence, understanding and compassion for the circumstances of us all.

TESTIMONY FOR TRIMET BOARD MEETING, Wednesday, December 11, 2019

“The return on investment for equality, compassion, empathy and social justice outweighs the return on investment for concrete.”

– Robbie Makinen on OPB’s Think Out Loud

From Drew Sinclair, undergraduate at PSU:

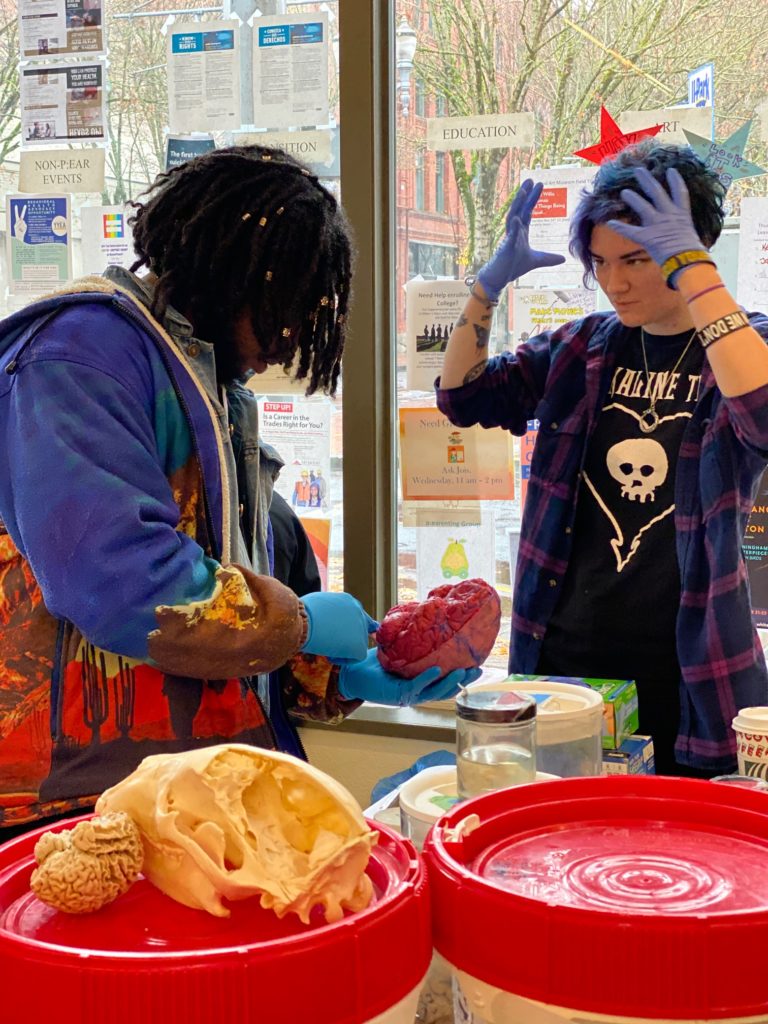

Hello. My name is Drew Sinclair, and I’m a senior undergraduate psychology major and student veteran. I’m also a part of a neuroscience outreach group called NW Noggin. Recently, I’ve sat down with homeless youth at p:ear to talk about brains and their experiences with trauma, addiction, legal issues, and just generally navigating a world that doesn’t seem made for them.

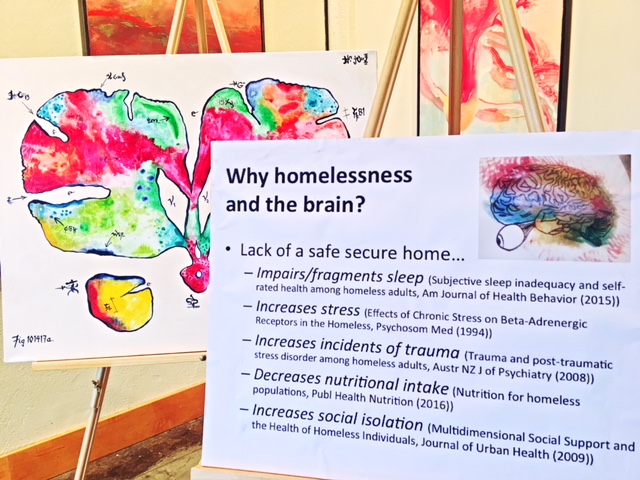

It may seem intuitive to say that a study showed that Marines with PTSD had significantly higher rates of demotions, drug use, and punitive punishments (Highfill-McRoy et al., 2010). I think we’d expect that. We’d expect people who’ve previously suffered enormous traumas to do poorly with following rules and norms. It feels much less intuitive to offer that another study showed that 83% of homeless youth surveyed in Seattle were sexually victimized on the street, and nearly 20% met diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Stewart et al., 2004). Now maybe that’s not quite what we’d expect – or possibly something we just tend not think about.

Neurologically speaking, PTSD may come in degrees of severity, but the types of dysfunction that are on the menu for those suffering are generally the same. The reason I use PTSD as my example is simply that most people are familiar with it. Studies are clear, though, that being homeless correlates with and exacerbates mental health disorders, and the longer one remains in these conditions, the worse the disorders are likely to become and the more difficult it is for recovery. Again, you all are probably feeling that this somehow intuitively makes sense.

What we are trying to suggest here is that if TriMet has an interest in bringing equity to our tri-county area, then the Board should have an interest in understanding what it means to make a commitment to providing transportation to the people who live here, which I have no doubt you do. In this commitment, I’m granting that you realize the importance of learning about the populations and demographics you serve — which I believe is why we’re being given the opportunity to stand here this morning. What I won’t grant is that the individuals who are suffering the most from homelessness are necessarily aware of, or fully capable of following the procedures laid out by the HOP system – or make their way to this meeting at 8:30am to explain why they can’t. I don’t think it’s intuitive for them to understand exactly what is happening to their brains (or to ours) or why it’s hard for many to follow certain procedures that seems reasonable to those with more resources. I hope, though, that you’ll find it a logical next step to take the growing body of research in neuroscience into consideration when you create the next iteration of your fare program. I’m grateful for your time.

From Bill Griesar at PSU/OHSU/NW Noggin:

Thank you for the opportunity to testify this morning. My name is Bill Griesar, and I teach about the brain and behavior (neuroscience) at Portland State University. Like many here, my family and I rely on TriMet to get around. My spouse and I board the bus daily to PSU and OHSU, and our two boys reach their own jobs by transit. I’m deeply aware and respectful of how important TriMet is to the economy and health of our community.

I’m also the Neuroscience Coordinator for an all volunteer outreach nonprofit known as Northwest Noggin (nwnoggin.org). My artist colleague Jeff Leake and I bring area college/grad students studying neuroscience and art – and real (extra!) human brains and art projects – into classrooms, youth correctional facilities, museums, pubs, coffee shops, tribal majority schools, the (Obama) White House, the US Congress, and rural public schools in Davenport, Grants Pass, Astoria and La Grande. When we visit K-12 students in PPS, or Beaverton, or Hillsboro, or David Douglas, many of our volunteers also rely on TriMet to join us.

One place we go is p:ear, an extraordinary Portland refuge for youth lacking access to housing. We’ve had powerful conversations with young people struggling with sleep, trauma, addiction, anxiety, depression, abandonment, bias – and often a sense that many, if not most people pass them by, without notice, as if they somehow weren’t valuable human members of our own community. We’ve discussed the dangers of being homeless – more traumatic injury and sleep deprivation, to name two – and how this impacts brain development and function.

Sleep deprivation, for example, prevents the nightly shrinkage of cells in the brain that wrap the tiny capillaries delivering blood. When that shrinkage does occur, for those of us getting good sleep in safe homes, the fluid that surrounds our brain and spinal cord (known as CSF) can penetrate and remove toxins that build up during the day. But in those of us without homes, there is no good sleep, no shrinkage, and the toxins stay. This makes everything our brains do more difficult, including how we perceive situations, memory, and coping with additional trauma and stress.

And if you or I were in similar circumstances, we’d have the same difficulties remembering, attending, planning, making decisions – or tapping a TriMet HOP card.

I’d like to call on the Board for more understanding, and more compassion for those experiencing homelessness, and for the stressful, even traumatic consequences of high punitive fines. During a recent visit to p:ear, we talked about the Street Roots vendor fined $175 for missing one “tap” on a MAX train. This is someone in severe circumstances, who despite these circumstances, was trying to reach his own job – and had pre-loaded his HOP card with $28 for the month! This is a success story, and deserves support – not a fine.

If you’re curious about how being homeless impacts our brains – and not just brains of those without homes, but our brains too, where we don’t see other people or appreciate them as fellow human beings, as the youth at p:ear experience – we’ve got a thorough post with relevant federally funded research up on our homepage at nwnoggin.org. I encourage you to check it out. Thank you for the opportunity to speak.

From John Phillips, Program Director at p:ear:

Good morning and thank you for your time.

My name is John Phillips and I am the Program Director at p:ear. At p:ear, we work with young people experiencing homelessness and housing instability. We work to build an inclusive community and celebrate the uniqueness and beauty of every individual the enters our space. We acknowledge that living on the streets exposes our youth to trauma daily and that every day is about survival. We offer them a space to have their physical and emotional needs met and perhaps begin to hope and dream of a future beyond homelessness. We assist our youth every day in navigating services related to healthcare, mental health, housing, addiction, education, nutrition, clothing, hygiene, parenting and many others.

An essential part of this process is reliant on Trimet. Trimet is the only mode of transportation the majority of our youth use to travel to and from these services. Trimet not only offers them transit, but safe transit. Taking the Max or hopping a bus allows our young people to avoid many of the threats they face walking the streets. We offer fare when possible but the need is too great. It has been my experience that many of our youth find themselves unable to pay fare on a daily basis, due to lack of income or access to resources.

Without fare, they must make a decision: a) They can take transit to their appointments, shelters, schooling, and other services, and risk a large fine b) they can possibly travel on foot and risk their safety or c) they can do remain where they are. Our youth choose to take the risk. Our youth choose to move forward. However, if they are stopped on transit without fare, the enormity of the fine is too great. If you do not have $1.25 or $2.50 to pay fare, a massive fine is insurmountable. They cannot pay. It creates another barrier for our youth and is a crushing defeat to their drive, motivation, and movement. I believe that supporting those in experiencing homelessness and housing instability is a community responsibility. I ask for compassion, more inclusive solutions, and equitable solutions; not higher fares and extreme fines for those without fare. Thank you.

Post edited by Bill Griesar, NW Noggin