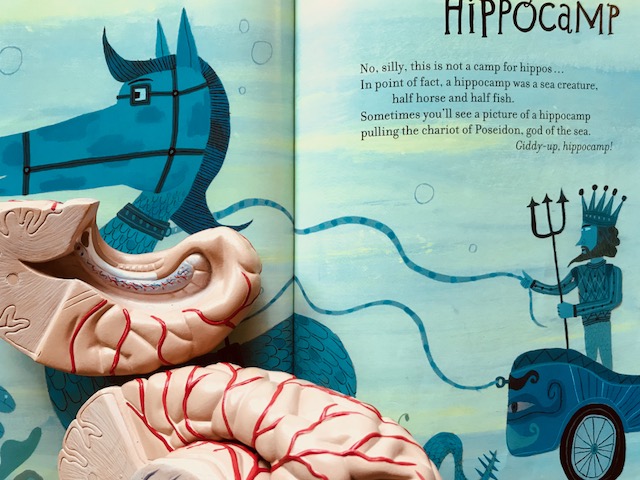

What do zombies have to do with neuroscience? What might vampires teach us about addiction? How does the repeated trauma of losing family members, friends – and werewolf lovers – impact our hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and our hippocampus? And why hasn’t the Hippocamp made an appearance on the show? (or am I just forgetting?)…

LEARN MORE: Memory function and the hippocampus

Millions of people have tuned in to watch the popular CW series Supernatural since the show debuted in 2004. It’s now in its 14th season, and returns for a 15th year this fall! Viewers are drawn to its menagerie of monsters, but also by the age old struggle against seemingly devastating and insurmountable odds faced by so many battling demons of their own…

“Carry on my wayward son

For there’ll be peace when you are done

Lay your weary head to rest

Don’t you cry no more”

–Kerry Livgren / Kansas

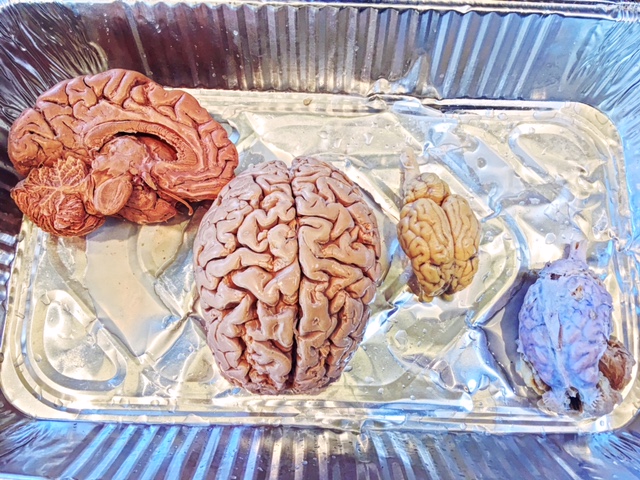

We were delighted to carry extra brains into the Oregon Convention Center this weekend! Bill Griesar of NW Noggin, Portland State University and OHSU joined Erin Currie, Adjunct Assistant Professor at PSU and Consultant at MyPsychgeek, and Janina Scarlett, a clinical psychologist, author and the originator of Superhero Therapy at Wizard World Comic-Con for a “spirited” discussion of Supernatural Psychology!

After our panel, we brought a table of brains into the Convention Center lobby for those curious to ask more questions about current neuroscience research on grief, trauma, sleep, memory, drugs, anxiety, depression, PTSD, biases, resilience and other aspects of our remarkable brains and behavior…

SO MUCH FUN – loads of neuroscience (and great costumes) at Comic-Con!

Noggin volunteers Joey Seuferling, Andrew Stanley, and Art Coordinator Jeff Leake were excited (depolarized even!) to talk more about research and the powerful influence of art…

Thank you Joey and Andrew for wrangling noggins with Freddy Krueger! Teenagers (and many adults) need more sleep (LEARN MORE: Brains, biofeedback & SLEEP @ Fort Vancouver!)

A definite highlight of the Comic-Con experience – The Unipiper!!!

Perception, cognition and behavior depend on brains and bodies. Neuroscience research is illuminating the rich diversity of our unique, developing – and also changeable – neural networks, and the personal and shared experiences which shape who we are…

“A Noiseless Patient Spider” 40×48 charcoal and graphite on paper 2011 by Jeff Leake

LEARN MORE: Supernatural Science: Battling Demons in the Brain

READ THE BOOK: Supernatural Psychology: Roads Less Traveled

HEAR THE PODCAST: Superhero Therapy Episode 14: Psychology of Supernatural

Dustin McGinnis, a musician, filmmaker, podcaster, and self-described “all-around fanboy” moderated Saturday’s panel, and offered thought-provoking questions on the relationship between storytelling in Supernatural and our own behavior and brains…

Dr. Janina Scarlett and Dustin McGinness

We were excited to discover audience interests, and enjoyed exploring the psychological and neuroscience aspects of battling demons, perceiving ghosts, and the power of family support and storytelling to illuminate, guide and heal. Some specific questions from Dustin below…

1. So, we’re all here because we’re family. Not family by blood, but family in our connection and reverence for this amazing TV show. “Family don’t end in blood,” right? Sam and Dean may be a family but they also consider others like Bobby and Cas to be their family too. What defines family and how does social support affect the characters and people in real life?

LEARN MORE: National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program

Families are complex. We all know this. As a gay, married father of two adopted Cambodian-born teenagers and one of the plaintiffs in the federal case (Geiger v. Kitzhaber, 2014) that brought marriage equality to Oregon, I am acutely aware of this complexity, too. People form strong bonds for many reasons, including shared interests, experiences, and history. There are efforts underway to better capture this diversity in psychological research; some examples are at the links below…

LEARN MORE: The Family and Family Structure Redefined for the Current Times

LEARN MORE: Family Complexity among Children in the United States

And while “family don’t end in blood,” knowledge of close biological relations can be useful for predicting or anticipating issues with your own health, including your mental health. A family history of alcohol use disorder (AUD), for example, increases the risk of excessive drinking, and knowing this might let you consider changes in behavior or environment to avoid dependence…

Image of Dean drinking from Giphy

“A wise man once told me family don’t end in blood, but it doesn’t start there either. Family cares about you, not what you can do for them. Family’s there through the good, bad, all of it. They got your back even when it hurts. That’s family” – Eric Kripke

LEARN MORE: Family History is Important for Your Health

LEARN MORE: What’s a “drink..?” At the Newmark for beer & brains

LEARN MORE: Genetics of Alcohol Use Disorder

LEARN MORE: Genetics and alcoholism

Members of a family (in Kripke’s sense, genetically linked or not) rely on each other, protect each other, understand each other, and trust each other. There is now fascinating research on some brain networks potentially involved.

“Masquerading as a man with a reason

My charade is the event of the season

And if I claim to be a wise man, it surely means that I don’t know…”

–Kerry Livgren / Kansas

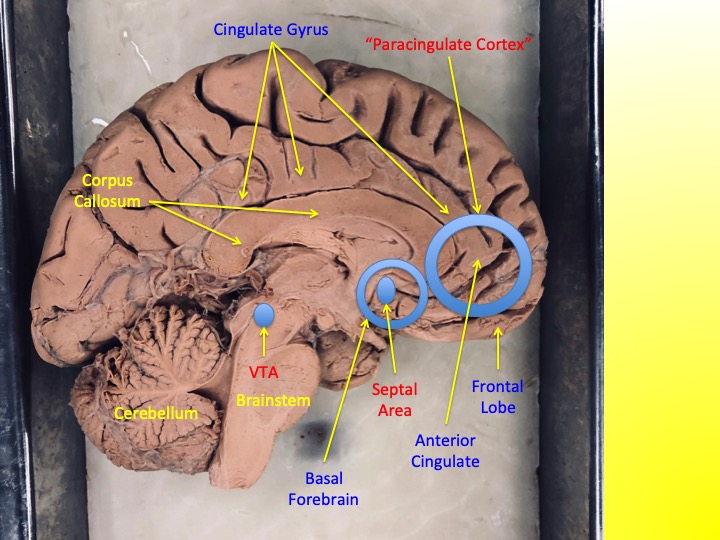

For example, one study found that conditional trust (“my trust depends on what you do next – Rowena“) and unconditional trust (“I believe in you Bobby“) are both associated with activity in frontal lobe brain networks involved in assessing the social intentions of others.

Increased blood flow in paracingulate regions associated with trust behavior

LEARN MORE: Neural correlates of trust

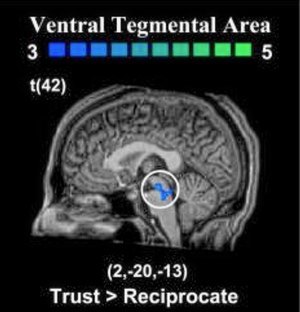

However, in situations eliciting conditional trust, the authors saw correlated activity in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a brainstem nucleus involved in anticipation and evaluation of reward…

LEARN MORE: Dopamine and reward seeking: the role of ventral tegmental area

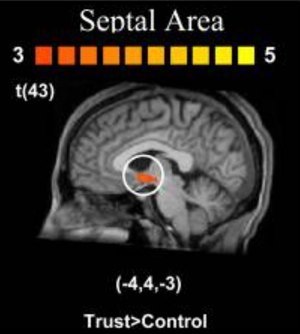

In contrast, unconditional trust (as measured in this particular study by the continued willingness to trust another subject to behave in your (shared) best interest in a “voluntary trust game”) lit up another area in the basal forebrain of the frontal lobe, the septal area, described by the authors as “a limbic region that has been demonstrated to modulate various aspects of social behavior including social memory and learning…”

Is this family? Different subcortical networks engaged by different degrees of social trust…

LEARN MORE: The septal region and social behavior

LEARN MORE: Neuroanatomical Substrates of Rodent Social Behavior

However these specific regions (basal forebrain, anterior cingulate) are deeply interconnected with additional parts of our brains absolutely critical for memory, decision making, attention, emotion, and knowing who we are, feeling what we want, understanding how and where we fit in…

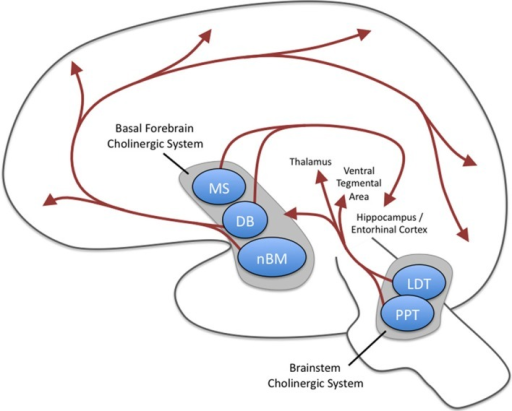

The septal area is part of the basal forebrain cholinergic system (those arrows are axons connecting it with different regions of the brain). Image from: Cholinergic modulation of cognitive processing

The basal forebrain, for example, is among the first regions lost in the development of Alzheimer’s dementia, while damage to the anterior cingulate can lead to a condition known as akinetic mutism (no moving, no talking, no apparent volition…). Brains (and families) are networks, and networks (both neural and social) ideally communicate, support each other, and share…

“Family’s everything you know” -Dean

2. What is it about this show that resonates with such a large and diverse group of fans?

“On a stormy sea of moving emotion

Tossed about I’m like a ship on the ocean…“

–Kerry Livgren / Kansas

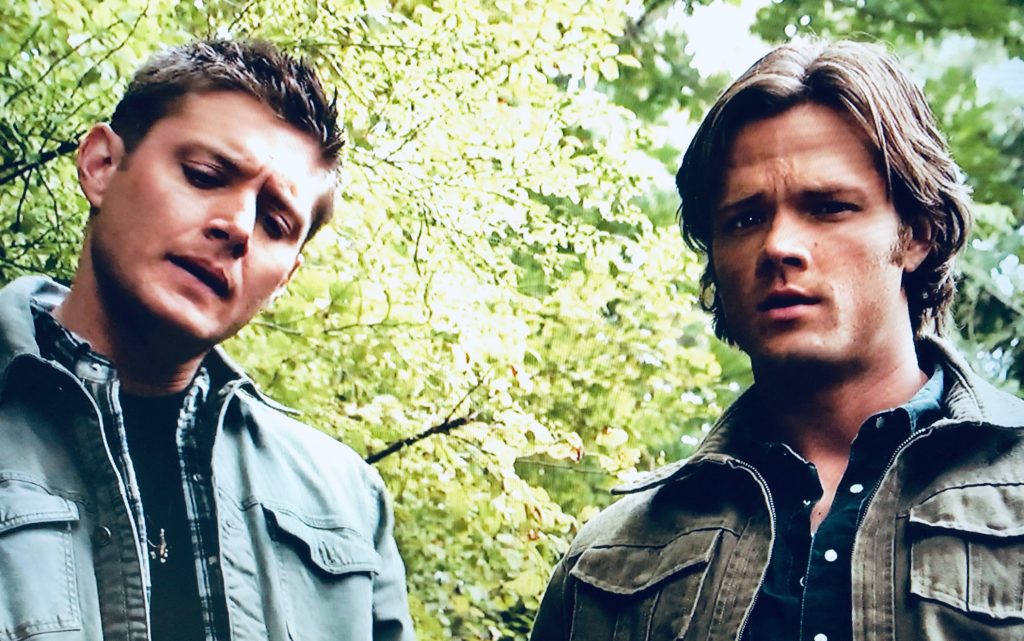

Brothers Sam and Dean suffer multiple traumatic losses throughout 14 seasons of this popular series, and cope with their pain differently, in both adaptive and maladaptive ways.

“You’re tailspinning man, and you refuse to talk about it and you won’t let me help you” -Sam to Dean, from Heart (season 2, episode 17)

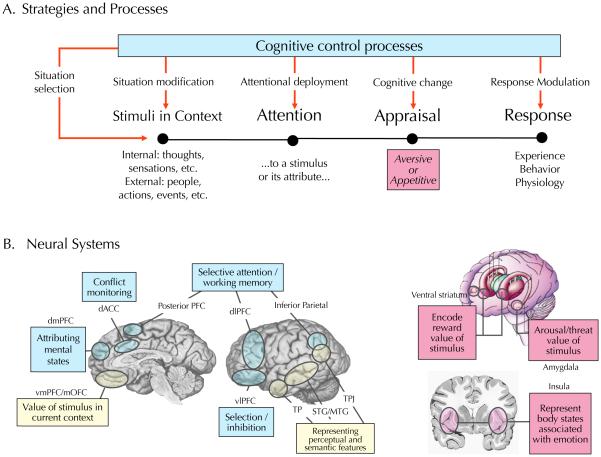

And certainly we all struggle to regulate our emotions, in response to the many uncertainties and tragedies in our own lives. Sam often aims for a strategy known as re-appraisal, by talking situations out with other people, including his brother, to consider new approaches. Dean, in contrast, tends towards suppression and distraction through alcohol and one night stands.

Re-appraisal is often a more effective strategy, partly because it prepares you to respond less fearfully or impulsively to (for example) a hex bag or a crossroads demon, rather than trying to clamp down on your emotions once a “fight or flight” response is in full swing.

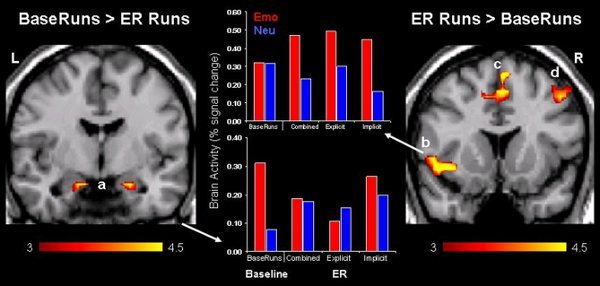

Cortical networks (indicated in blue) are involved in perceptual aspects of what you’re experiencing, attending to and deciding, while networks in red (involving both subcortical and cortical regions) drive faster, more impulsive, emotional responses…

There are many moving, therapeutic conversations between the brothers, and between the brothers and other characters (including fellow hunter Bobby Singer and the angel Castiel), involving efforts to remind each other of family loyalty and support, and consider more positive and effective options.

Efforts to regulate emotions through re-appraisal and suppression tend to decrease activity in a brain region known as the amygdala (a), while increasing the activity of networks in the frontal lobe, including the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC) (b), dorsolateral PFC (d), and medial PFC (c) that are critical for inhibiting impulsive emotional responses…

LEARN MORE: Brain Imaging Investigation of the Neural Correlates of Emotion Regulation

When we see characters struggle on a celebrated TV show, it resonates with our own traumatic experiences. You are not alone in experiencing stress, and one way to cope is to find meaning – through connection with others, loyalty to family, a life purpose,…

3. The show is full of monsters and demons. How can these be used to help us understand our own experiences?

First off, there are several published case studies of “vampiristic” behavior!

From Nosferatu (1922)

LEARN MORE: Vampirism—A Clinical Condition

LEARN MORE: Vampiristic behaviors in a patient with traumatic brain injury induced disinhibition

There is quite a long history of reported encounters with werewolves…

LEARN MORE: Battling demons with medical authority: werewolves, physicians and rationalization

Dean Winchester, of course, in addition to his drinking (which Sam also appears to do more and more as their traumas accumulate) clearly copes by fighting vampires, werewolves, and other monsters (“My peace is helping people, working cases; that’s all I want to do”)…

Certainly a quicker, well-placed, fear or anger-driven emotional, impulsive response is essential for the many life-threatening circumstances encountered in Supernatural…

Ahhh…hell no! Amygdala activation and impulsive lashing out are guaranteed…

If a Wendigo is racing towards you at lightning speed, you’ll want all the fight or flight activation you can get! And of course, a Rakshasa dressed as a clown is going to increase Sam’s heart rate and blood pressure (mine too!) no matter how much re-appraisal he’s done…

But where is the Hippocamp? Image/text from Greece! Rome! Monsters! by John Harris. Illustration by Calef Brown. LEARN MORE: White Matter on Wy’East

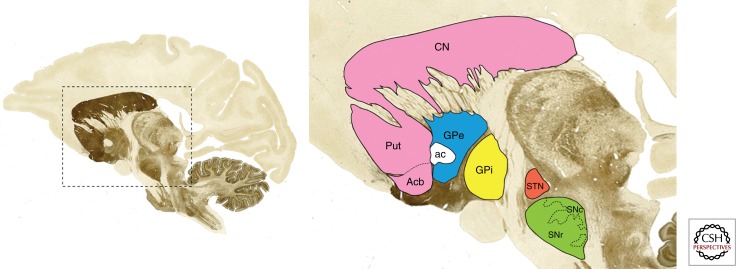

Through trial and error, risk and consequence, and a lot of initially conscious struggle, Dean has developed useful fighting skills, and clearly enters a flow state when engaging with monsters in the show. Much of his quick, adroit responses to often grisly, deadly “stimuli” are now likely dependent on proficient subcortical networks, like those in a set of circuits known as the basal ganglia…

Muscle memory for fighting monsters is in the brain – at least partly in the basal ganglia!

LEARN MORE: Functional Neuroanatomy of the Basal Ganglia

LEARN MORE: Basal ganglia @ Beaumont!

And of course these are gripping stories, with elements drawn from Greek, Native American, Egyptian, Celtic and Biblical tales, which offer us training in actions and consequences, as we viscerally follow the travails and conflicts of the Winchesters and their extended family. Stories are guides, roadmaps, and representations of genuine human struggles and experience. Stories structurally and functionally change our brains to reflect the social and cultural expectations of our own community…

Again, you are not alone…

LEARN MORE: Maturation of the adolescent brain

LEARN MORE: Diamond advice: brains, art, stories & play

LEARN MORE: Until the story takes shape

4. Sam and Dean, as well Castiel and other hunters, like Bobby have all faced and sometimes run away from their own traumatic origins. What does the show teach us about coping with trauma?

Traumatic, stressful experiences are very common, and also re-wire brains.

Rubylith brain by artist Joshua Abraham…

LEARN MORE: Feeling stressed?

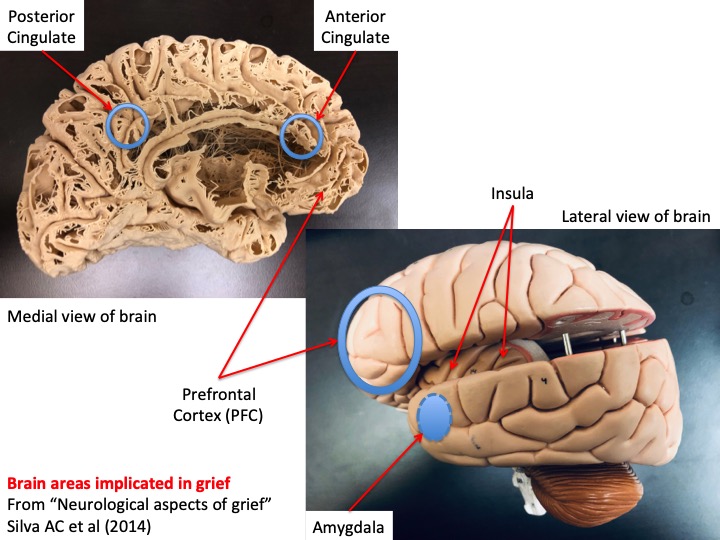

Grief from bereavement, for example, often leads to hallucinatory sightings of lost loved ones, or people may hear their voices after they are gone. Areas of the brain involved in the perception of faces and voices are active in these circumstances; it’s as if a limb has been cut but the brain areas in this case mapping memories and details of the lost partner or friend persist, creating phantoms…

Mary appears to Dean; Image from Supernatural Fandom

LEARN MORE: Bereavement hallucinations after the loss of a spouse

LEARN MORE: Neural correlates of evoked phantom limb sensations

LEARN MORE: Neurological aspects of grief

However, not everyone responds to stresses in the same way. Some are excited and, like Dean, Mary and other hunters, may appreciate the surge in available energy and leap to attack. In contrast, some may panic, sweat, withdraw, and feel tense, anxious, nervous and depressed.

“Dripping rainbows,” by Qu’ran @ p:ear, from Homelessness & the Brain

“It’s not stress that kills us, it is our reaction to it.” –Hans Selye

Stress is, first and foremost, a bodily emotional response – as that Wendigo circles, there are palpable, physical changes in our bodies, including changes in heart rate, blood pressure, circulating hormone levels, facial expressions and posture. These body changes are also mapped in brain regions which support conscious perceptions (or feelings) of our emotions – the anxiety, perhaps the terror, or in some cases the excitement and exhilaration of an experience where the body is prepared and ready for action…

Supernatural — “Alpha and Omega” — Jared Padalecki as Sam and Jensen Ackles as Dean — Photo: Katie Yu/The CW © 2016 The CW Network, LLC. All Rights Reserved; Image source

LEARN MORE: Physiology of the Autonomic Nervous System

“Carry on my wayward son

For there’ll be peace when you are done”

–Kerry Livgren / Kansas

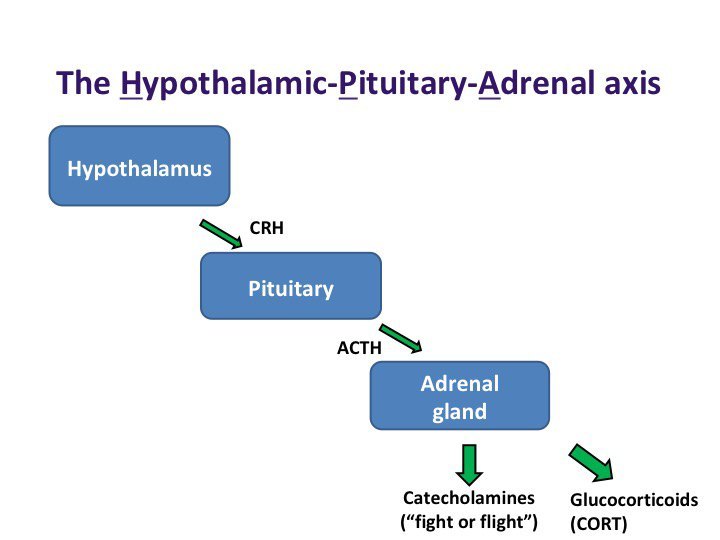

But not just yet! The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (or HPA) axis is a core biological component of our stress response. These three structures, two (the hypothalamus and pituitary gland) found in the brain and one (the adrenal glands) located on top of each kidney, talk with each other through the release of chemicals called hormones, which travel through the blood to reach and influence their targets…

Slide from Velo Cult presentation by Eileen Torres, OHSU Behavioral Neuroscience

HPA activation is critical for survival, and prepares you for handling demanding situations. One brain target of cortisol (CORT), a stress hormone released by the adrenal glands, is the hippocampus, a region essential for memory. Acute (short-term) stress improves memory – our memories are enhanced by emotionally significant events…

Stress physically changes our brains, and the HPA axis is found in many species as a highly conserved biological network which helps translate limited stressful experiences into neural plasticity (the ability of neurons to form new connections, and change how you remember, feel and respond). Mild stressors can even lead to neurogenesis – the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus, part of a network of brain regions important for (remember..?)…memory!

LEARN MORE: Acute stress enhances adult rat hippocampal neurogenesis

However, too much stress – chronic stress – is detrimental.

For example, chronic immobilization stress (in rats) causes their hippocampal brain cells to lose dendrites, and thus their synaptic connections, impairing memory.

Supernatural — “Alex Annie Alexis Ann” — Pictured (L-R): Jared Padalecki as Sam and Reilly Dolman as Connor — Credit: Katie Yu/The CW — © 2014 The CW Network, LLC. All Rights Reserved, Image Source

In contrast, neurons in the amygdala respond by extensively branching, forming new connections. The amygdala is a major player in our emotional response to threatening external stimuli, increasing sympathetic “fight or flight” reactions, and causing us to freeze in fear. It also directly activates the HPA axis…

Kids at Ogden Elementary drawing what scares them on a paper amygdala…

LEARN MORE: Occipital lobes at Ogden!

LEARN MORE: Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons

LEARN MORE: Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD

Chronic stress also impairs hippocampal neurogenesis, so we get fewer new neurons. It can also kill off neurons, and stress-related neurodegeneration may contribute to certain diseases like Alzheimer’s…

LEARN MORE: Chronic Stress and Glucocorticoids: From Neuronal Plasticity to Neurodegeneration

We’ve also referenced actor Jared Padelecki’s powerful, important and effective efforts to educate about depression through our outreach with NW Noggin…

LEARN MORE: The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress

“So tell me about it.” – Sam to Dean. “No…I’m not gonna talk about it…You really think some heart to heart, a little sharing and caring, is going to change anything? I’m not talking about a bad day here…” From Wishful Thinking (Season 4, episode 8)

Brittany Alperin from Behavioral Neuroscience at OHSU and artist Sienna Morris explored ways to better cope with our own demons resulting from trauma, depression and anxiety, through (among other approaches) the practice of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku), and creating and viewing art…

Bathing your brain @ Velo

5. No character is truly good or bad. Crowley is a demon but is honorable at times. Castiel is an Angel, but evil sometimes. What does it say about a show where so many beloved characters exist in the grey?

Families are complex, and people are too. And people (and demons, and monsters, and angels) can sometimes surprise you, and change (you included).

6. What can you tell us about the neuroscience of facing monsters?

Powerful traumatic experiences can not only physically change our brains, but also our chromosomes – not by changing the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA (the “code” itself), but by adding or removing specific chemical constituents that alter the future expression of genes. This changes which genes are subsequently expressed, and/or to what extent – thus changing the very structure and function of our brains and bodies…

Some of these epigenetic (“above the genome”) alterations are heritable…

LEARN MORE: What Do You Mean, “Epigenetic”?

LEARN MORE: Epigenetics across the human lifespan

LEARN MORE: Topical Review: The Emerging Field of Epigenetics: Informing Models of Pediatric Trauma and Physical Health

LEARN MORE: The intergenerational effects of war on the health of children

LEARN MORE: Epigenetics and memory: causes, consequences and treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction

LEARN MORE: Epigenetic transmission of Holocaust trauma: can nightmares be inherited?

LEARN MORE: Paternal transmission of early life traumatization through epigenetics: Do fathers play a role?

7. Is there a message you would hope to leave to our fellow Supernatural fans here today?

All this also suggests that current experiences matter, and not just for us. How we act today and the challenges and consequences we face and how we respond not only impacts our own brains, but can influence the brains and futures of our own children and grandchildren. Positive influences, choices and decisions also chemically tag chromosomes, and perhaps some epigenetic changes promote recovery – and the ability to cope, and even thrive.

Social engagement and connection contribute to our resilience, through the families we make, the communities we build, the art we create, and the shared stories that offer entertainment, direction, guidance and support…

“Carry on my wayward son…”

–Kerry Livgren / Kansas

Thank you Erin, Janina & Dustin!

Supernatural Science: Battling Demons in the Brain