“I just hope that more people will ignore the fatalism of the argument that we are beyond repair. We are not beyond repair. We are never beyond repair.” ~Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Noggin @ The Mac, McLoughlin Middle School, Vancouver WA

At NW Noggin, we don’t focus our science communication efforts on costly and exclusive conferences, programs, or events. The public pays for neuroscience research and education, income inequality is rising fast, and explicit and implicit bias still exclude far too many people from access to useful, genuine, actionable knowledge about their own brains and behavior.

And some of the most compelling, challenging, and effective ideas – and extraordinary art, stories, insights and action – come from going places, listening, and being present…

“I want to speak to people directly as much as possible.” ~Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

LEARN MORE: All is in motion, is growing, is you

LEARN MORE: Community Neuroscience: Interview with the Dana Foundation!

We particularly love visiting p:ear, a community center offering essential services and support for Portland’s homeless youth. P:ear provides a warm, welcoming, arts-filled educational space downtown, filled with caring staff and volunteers for young people, many of whom lack access to safe housing. This spring we witnessed an incident involving Portland Police that added to our evidence-based conviction that more public investment in places like p:ear would better address genuine community needs than current budgetary approaches…

A small fraction of our accomplished science communicators this month at p:ear!

LEARN MORE: Listening to testimony @ p:ear

SUPPORT P:EAR: How you can help

On a bright March morning bursting with the blossoms of spring, our host of eager young volunteer educators wheeled an artist-designed cart of noggins into the p:ear space at NW 6th and Flanders.

Over the last four weeks we’ve happily welcomed Aaron Eisen, Cam Howard, Greyson Moore, Kyle Stinson, Jordan Ray, Emily Burgess, Diane Duncan, Brenda Yan, Mary Lerner, Andrew Stanley, Darrin Lane, Madi Cho-Richmond, Isabella Maranghi, Jesus Martinez, Amber Schwartz and Isidro Chan from Portland State University (“Let Knowledge Serve the City”), Christine Lee-Roth and Anita Randolph from OHSU (“Where Healing, Teaching and Discovery Come Together”), Catherine Caine from Waikiki Elementary, and Joey Seuferling from NW Noggin (“Building Networks in the Community through Neuroscience Education and Art”)…

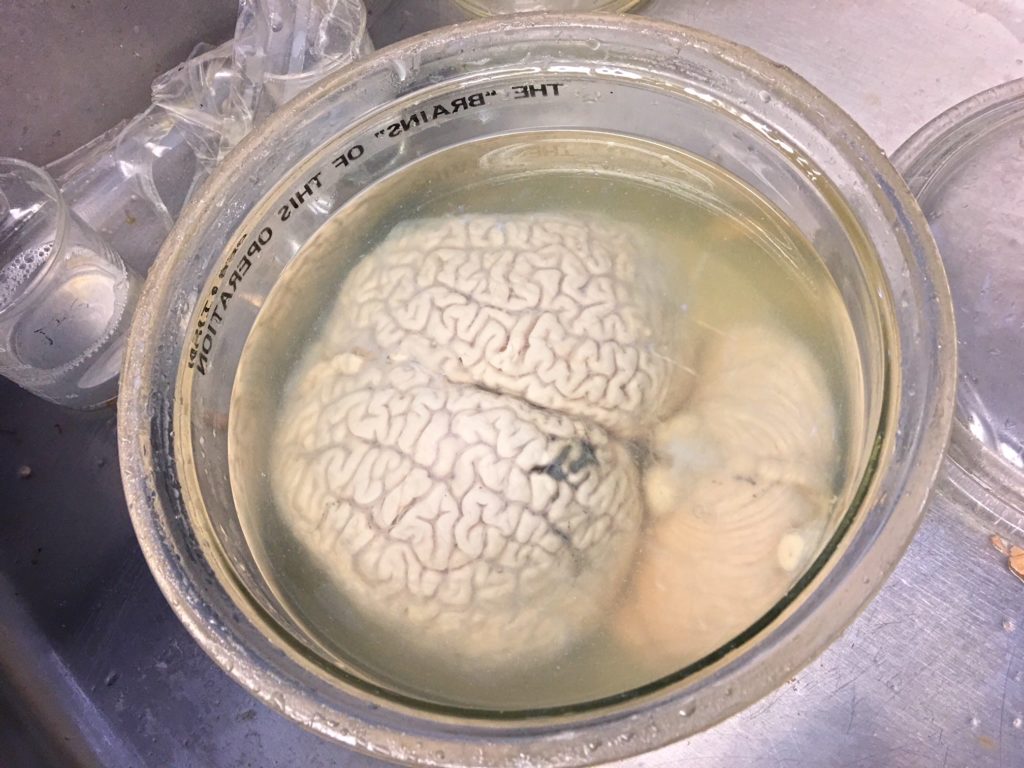

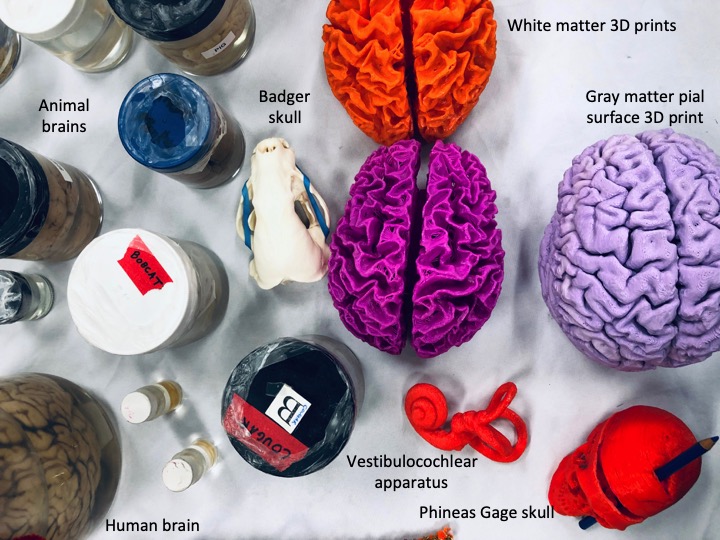

This particular morning, as we set out more jars of real brains, brains in acrylic, brains in 3D printed PLA, pipe cleaners, skulls, electrodes and electrophysiological equipment, p:ear Art Director Will Kendall introduced us to a young man who had been struck in the back of his head – with an axe!

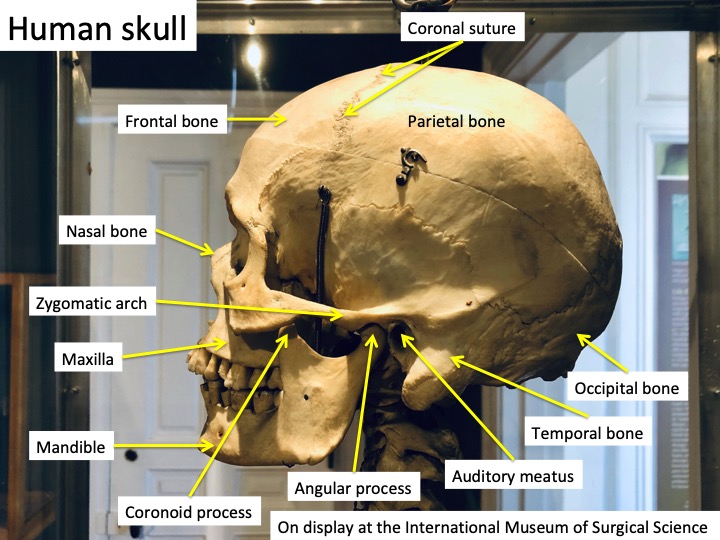

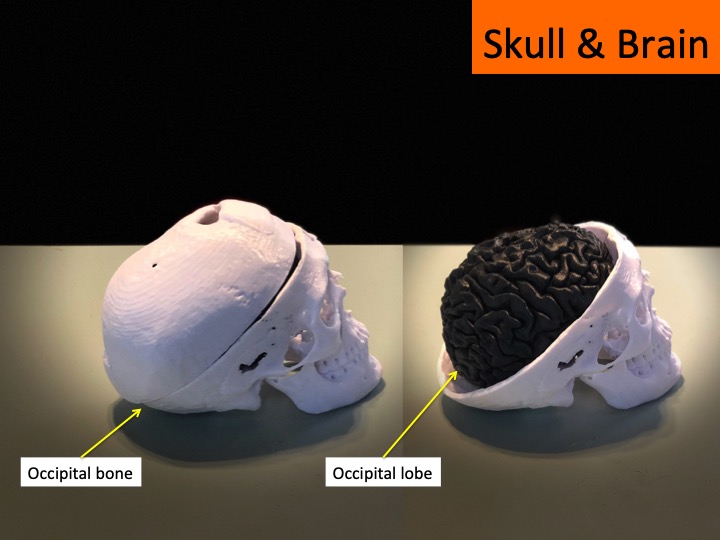

People without homes are more likely to suffer a traumatic brain injury (TBI), and this youth was apparently assaulted while sleeping outdoors. We asked if he’d tell his story, and he showed us the vicious scar across the back of his head. The force of the axe had shattered his occipital bone, and he spent two days in a hospital before waking up.

LEARN MORE: Head injury and mortality in the homeless

LEARN MORE: The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people

LEARN MORE: Traumatic brain injury among people who are homeless: a systematic review

We asked if he’d experienced any changes in vision since the assault, and he said yes. “Now I see bright, blinking, sharp and jagged lines, forming part of a circle, starting small and then expanding. In the middle of this space it gets darker and I can’t see anything.” We asked if it ever stopped, allowing him to see, and he said yes. “It doesn’t happen all the time. It happens a lot when I’m tired. And I’m tired a lot.”

Each TBI is different. Yet two common consequences are slower information processing and fatigue. A traumatic impact will transit through bone (in this case a shattered bone) and reverberate across the brain, yanking at complex neural connections, initiating inflammatory responses and undermining the ability of distributed brain regions to collaborate. It now takes more effort to properly coordinate these networks, which are essential for perception, cognition (including regulation of our emotions) and behavior…

Giving yourself time to rest helps your brain begin the long process of recovery. Letting others know about your TBI, and your need to take time and withdraw from social engagement when you’re feeling tired and overwhelmed promotes the reestablishment of brain networks, and a healthier outcome…

LEARN MORE: Redefining TBI through Art

LEARN MORE: Traumatic Brain Injury Information Page

LEARN MORE: Traumatic Brain Injury: Hope Through Research

LEARN MORE: Addressing TBI through research, outreach & art

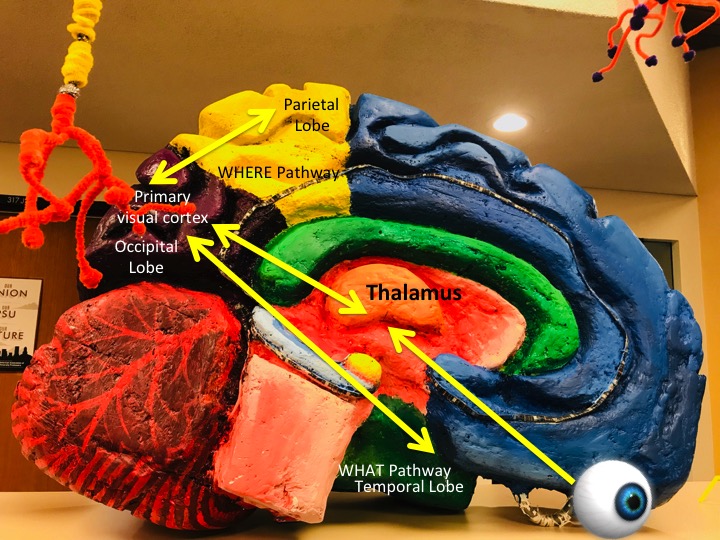

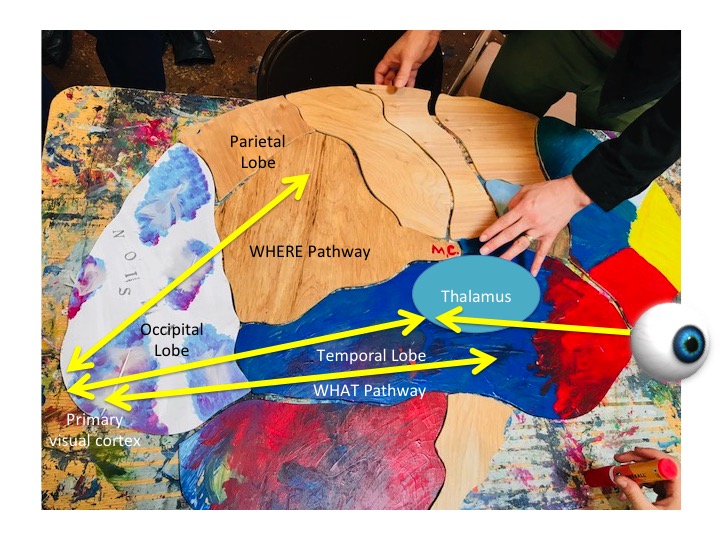

Visual changes may happen, too, especially after a blow to the back of the head. The occipital lobes lie beneath the occipital bone, and these are the first neocortical regions to receive visual details from our eyes. Trauma may impact our perception through potentially dangerous changes in blood flow and/or intraocular pressure, so it’s extremely disturbing that a young man suffering this sort of injury remains homeless, without access to additional medical care.

LEARN MORE: Head trauma can cause transient elevation of intraocular pressure in patients with open angle glaucoma

LEARN MORE: Hypovolemic ischemic optic neuropathy

However the fact that his shimmering, jagged visual experience – what’s known as a scintillating scotoma – only appears occasionally, while at other times he sees normally, is positive. Scotomas are often associated with subsequent migraine headaches, but this young man said he didn’t experience headache pain following his vivid scotomas…

SOURCE: Visual Aura and Scotomas: What Do They Indicate?

LEARN MORE: Migraine aura pathophysiology: the role of blood vessels and microembolisation

LEARN MORE: NIH NINDS Migraine Information Page

We did ask if he ever saw anything else during these visual interruptions. He looked at us quizzically. “What do you mean?” “Well,” we replied, “maybe something unexpected – something you weren’t used to seeing, or perhaps something familiar but in an unusual place…”

“I haven’t told anyone about this,” he said. “They’d think I’m crazy, or on drugs. But…I seriously saw – like it was right here – a dolphin leap in front of me, in the middle of the sparkling lights!”

A minke whale brain, courtesy of Debbie Duffield, Portland State University

“I’ve also seen faces sometimes – but faces with big teeth, or stretched out ears and noses…”

Neural networks in our brain’s temporal lobes make up our visual “What Pathway,” and become organized with visual experience to allow us to perceive what’s there, be it a bicycle, a brain, or a dolphin. When there is a loss of visual sensory input (in this case due to scotomas following TBI), brains are sometimes freer to activate these networks that underlie our conscious visual perception of various objects in the world.

LEARN MORE: Hallucinations @ HeLa High

These vivid visual hallucinations characterize a disorder known as Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS). CBS remains an under-reported condition, as many people are concerned, like this young man, about their mental state, perceptions of their mental state, and/or about the consequences of being mis-diagnosed with dementia or other serious disorders.

“For reasons that remain unclear, about 20 percent of people with neuro-ophthalmic vision loss develop the vivid, recurrent visual hallucinations that characterize Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS).” – eyewire

LEARN MORE: Highlights from The American Academy of Ophthalmology annual conference

LEARN MORE: Hallucinations Experienced by Visually Impaired: Charles Bonnet Syndrome

However, knowing about the neurophysiological underpinnings of CBS helps people learn to live with these occasional symptoms and reduces stress, improving health and quality of life. This young man, who suffered an appalling injury, was very interested in examining the brains we’d brought to p:ear, identifying the location of the occipital and temporal lobes, and asking questions about his experience. Young brains have extraordinary plasticity, and ability to appropriately re-wire with proper care and support.

LEARN MORE: Impact of Age on Long-term Recovery From Traumatic Brain Injury

After about 15 minutes, he was tired. But he now knew he needed to give his brain a rest, and that was ok.

Our volunteers are learning too. What they study and research, often with public dollars, has great value and importance to many people in our community, including Portland youth without safe places to sleep. Instead of subsidizing exclusive “science communication” conferences for isolated academics, or paying tuition to practice another scripted, inflexible “elevator pitch,” these young volunteers go places, leave the classroom, lab and conference, genuinely discuss relevant neuroscience, make art, connect and listen to those who might teach them something and benefit most from federal research…

Come join us!

Applied neuroscience and STEAM outreach can be practiced everywhere… 😉

LEARN MORE: Synapsing in San Diego

LEARN MORE: Community Neuroscience: How to Build an Outreach Organization

LEARN MORE: Noggin @ p:ear