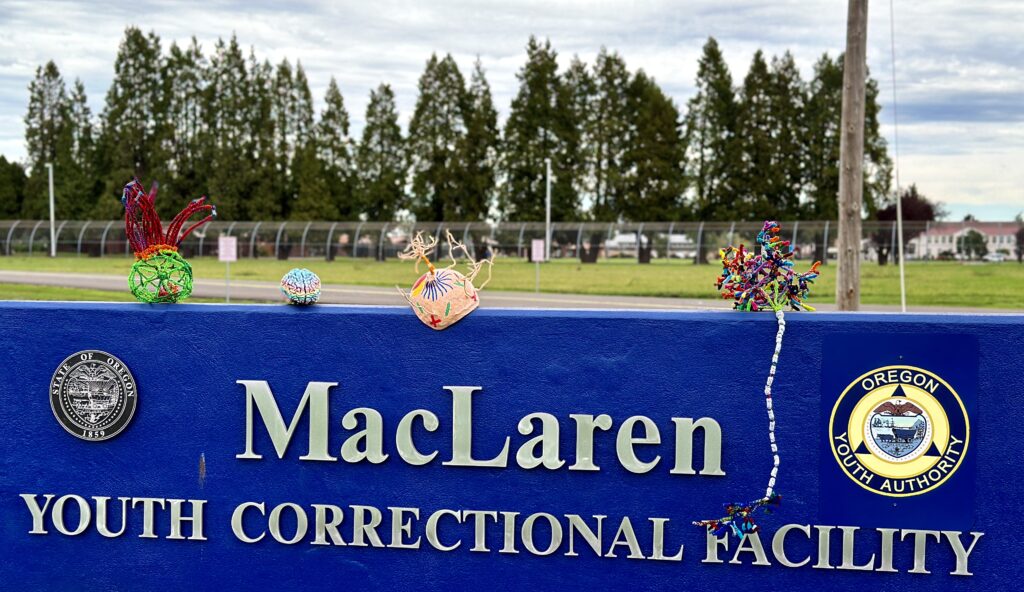

Northwest Noggin returned to the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility this fall, to meet with more young people curious about the brain, and the policy implications of ongoing neuroscience research on adolescent development, bias, trauma, drugs, and mental health in terms of education, healthcare, criminal justice and the law.

We’ve visited MacLaren on multiple occasions, and detailed descriptions, including questions youth asked, artwork we created and research we discussed are available at the following links:

Myelinating @ MacLaren!

LEARN MORE: Myelinating @ MacLaren!

All is in motion, is growing, is you

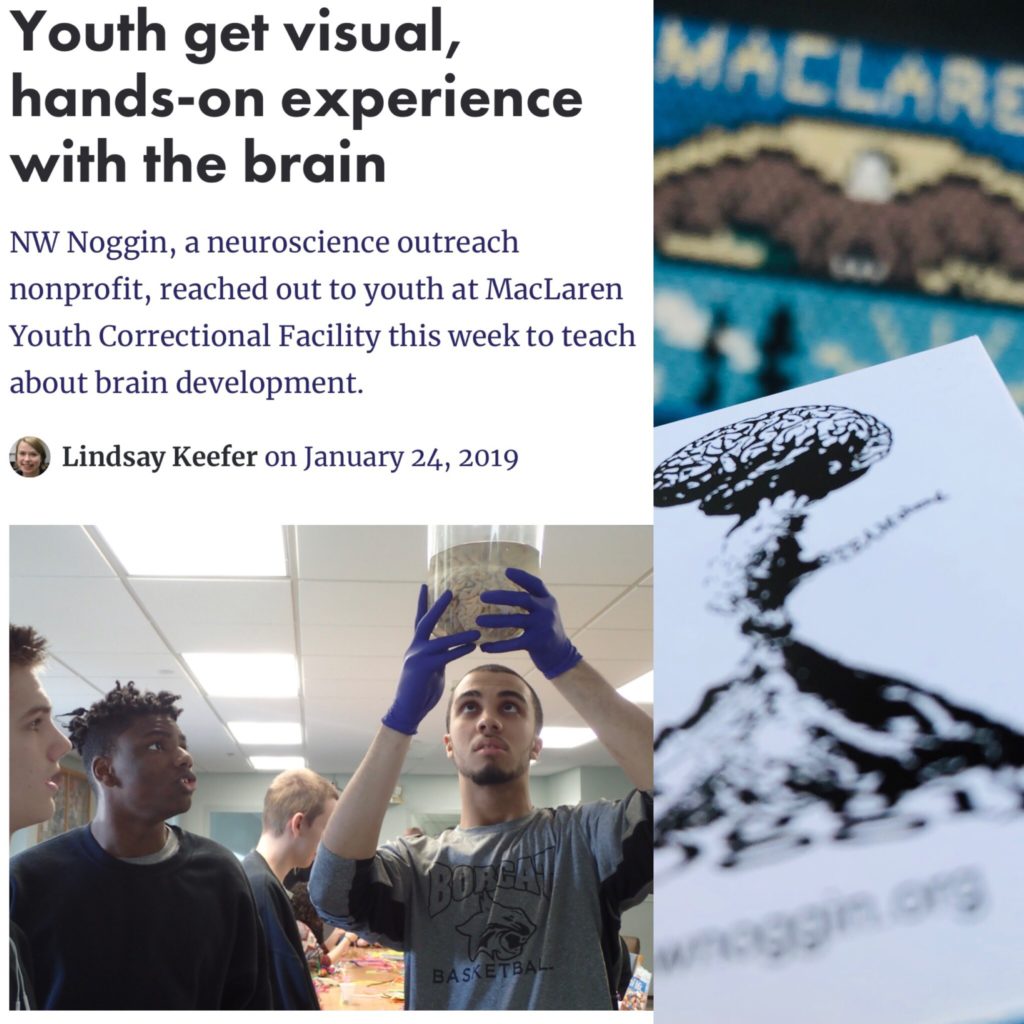

LEARN MORE: Youth get visual, hands-on experience with the brain

LEARN MORE: All is in motion, is growing, is you

Corrections, Bias & Brains

LEARN MORE: Corrections, Bias & Brains

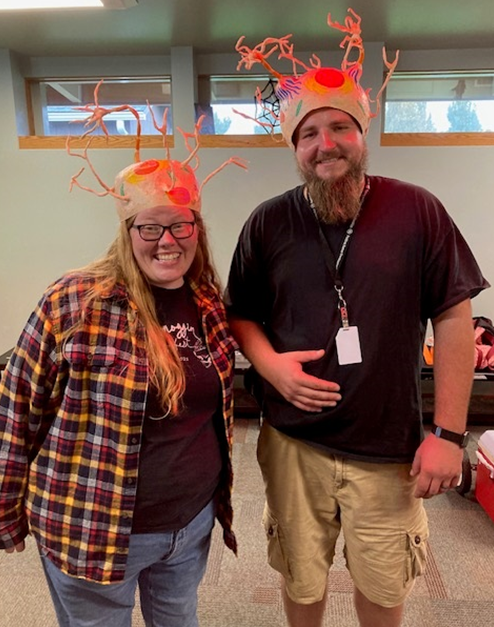

This time we were joined by undergraduates Alexandria Bills, Emilee Brnusak, Martin Lemke, Julian Rodriguez, Conner Corbett, Brooke Hyland, Khelen Walsh, Anthony Nguyen, Eric Nguyen and Kadi Rae Smith from Portland State University, along with Angela Hendrix, Bill Griesar and Jeff Leake from Northwest Noggin.

“It was a great trip full of inquisitive minds I was very grateful to be part of it.”

— Martin Lemke, undergraduate at PSU

FROM CONNER CORBETT

I heard some great practical questions about perception asked by young people at MacLaren, including:

“How does sound travel through my brain?“

“What does the back of my brain have to do with my listening to sounds?”

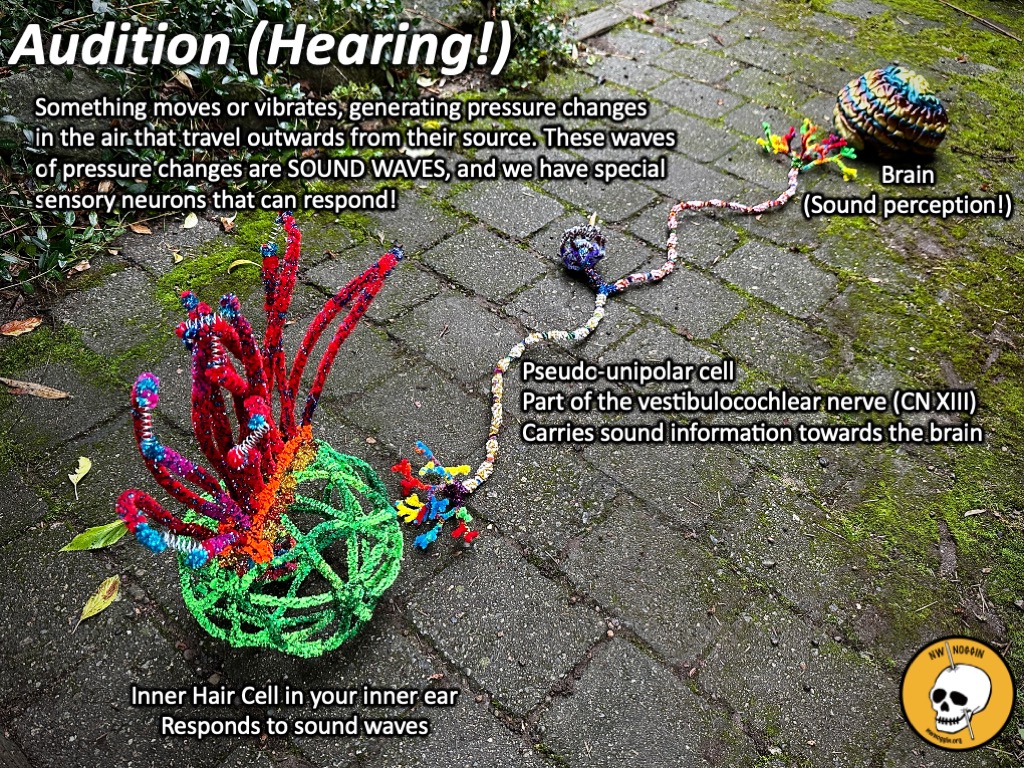

Here is where I got to elaborate a bit on the neural networks involved in auditory processing. Sound waves are traveling waves of pressure set off by something moving or vibrating. Sound waves typically propagate (move) through the air, but they can also travel through other substances, including liquids like water (can you hear underwater?).

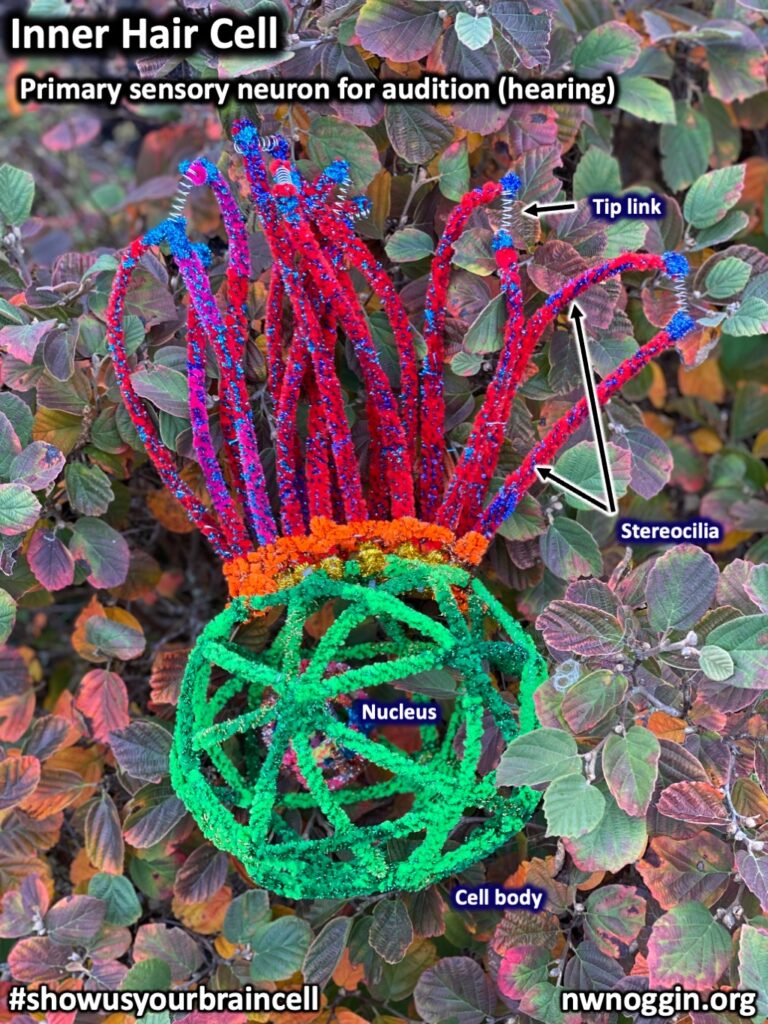

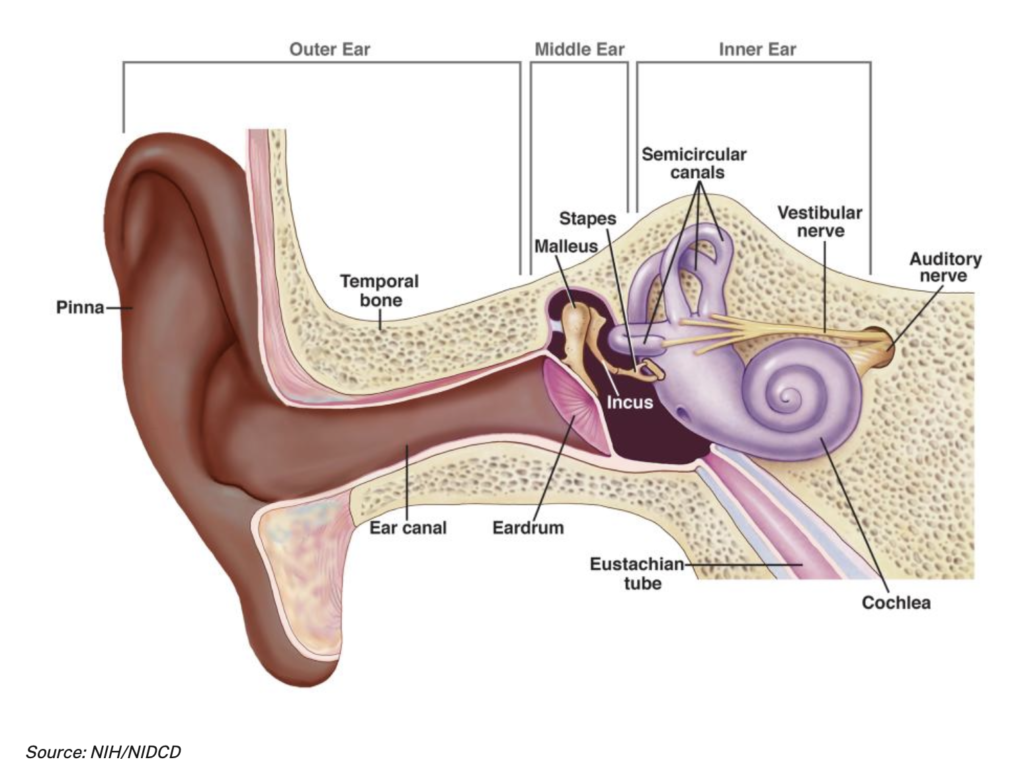

Deep inside your ear there are specialized sensory neurons known as inner hair cells that physically move in response to those pressure waves of sound, waving their hair-like stereocilia in response, which pulls on springs at their tips (stretching the spring-like tip links), which open and close tiny protein channels in the cell’s membrane and let electric currents pass through!

These inner hair cells are found inside a coiled, snail-like structure in your inner ear known as the cochlea (Latin for “snail”).

LEARN MORE: How Do We Hear? (from the NIH)

Once activated by sound waves, these inner hair cells release chemicals (neurotransmitters) on to other, longer cells that carry currents (and information about sound!) into the brain. The wire-like processes of these longer cells (known as pseudo-unipolar cells) form the auditory cables of your vestibulocochlear nerve, or the eighth cranial nerve CN XIII), which carries details about both audition (hearing) and vestibular function (balance and acceleration).

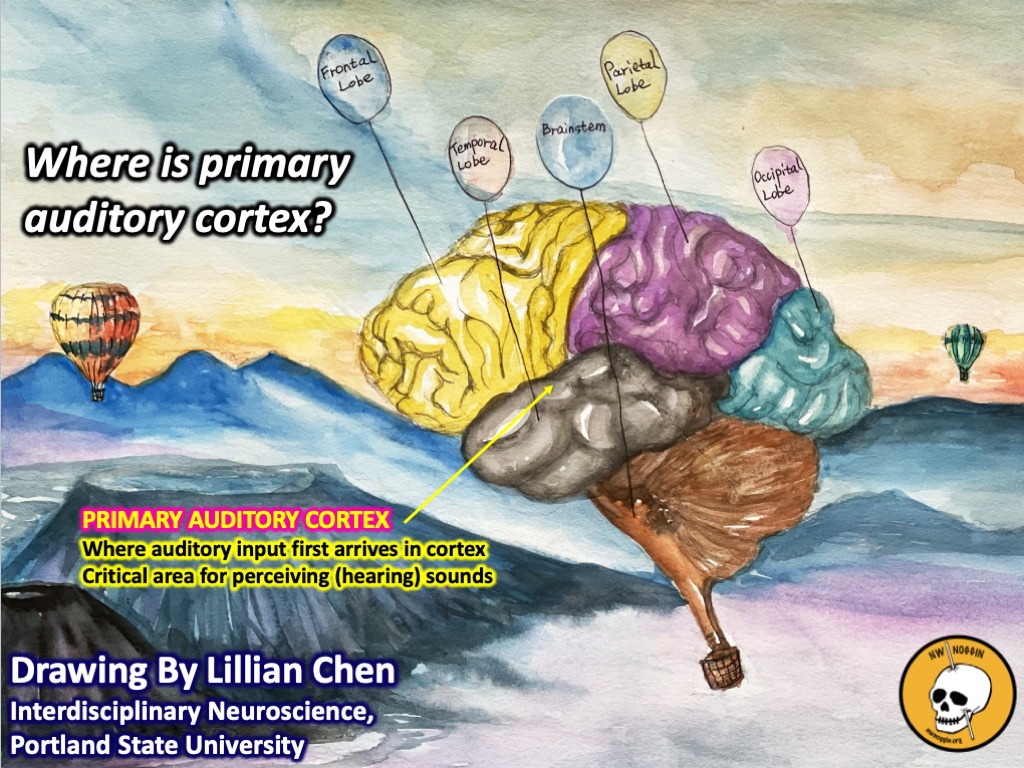

Once in the brain, the sound information is carried along an additional network of interconnected neurons, from your brainstem where the sound information initially arrives ultimately into the temporal lobes of your cortex, which support your ability to perceive (consciously hear) the sounds.

LEARN MORE: Helping Hair Cells @ Velo

LEARN MORE: Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology

LEARN MORE: Hands on Brains!

“Does this brain I’m holding today have the same texture as the one in my head?“

Not at all – the cadaver brains we bring have been fixed in a chemical bath that toughens them up so they can be held by lots of people. The living brain is much softer, and milky pink, fed by blood vessels that make it move rhythmically with changes in blood pressure. When surgeons need to remove part of the brain for medical reasons, they don’t typically use scalpels – but rather suction!

LEARN MORE: What is brain surgery like?

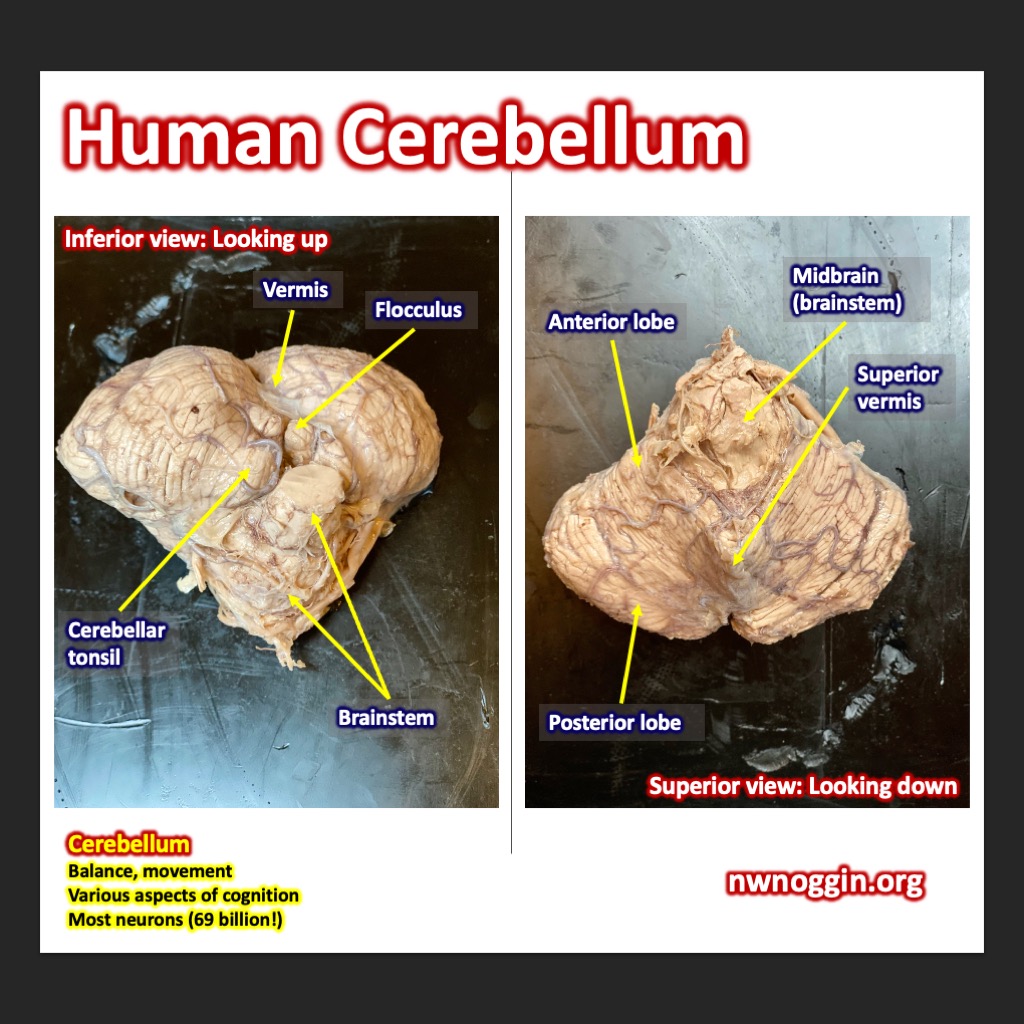

“What does the cerebellum do?”

The cerebellum (Latin for “little brain”) is a fascinating brain area that contains by far the most neurons (it’s home to 69 billion out of the 86 billion found in the typical human adult!). Neural networks here are known to support the coordination of our movements, repetitive emotional expressions like laughter and crying, and the integration of vestibular information (balance and acceleration) into how we move. However researchers are finding compelling evidence of cerebellar involvement in a host of other complex cognitive abilities, from language to decision making.

LEARN MORE: Physiology of the cerebellum

LEARN MORE: New Findings Reveal Surprising Role of the Cerebellum in Reward and Social Behaviors

An amazing statement from an 8th grader at MacLaren: “I think of the brain as a network of cells that is important for every part of our functioning, when I go to high school next year I plan to take human biology classes.” This same student proceeded to compare the brain he was holding, to the brain diagram and identify the different parts. He was hungry for learning science.

FROM ALEXANDRIA BILLS

It is a unique experience to hold a human brain and talk about brain cells to begin with, so to be able to bring that to the youth at the correctional facility I think is pretty impactful.

One conversation that struck me was talking about one of the youths’ family members’ goals to go into the healthcare field and that because of this he wanted to as well. I think it’s important to note that some kids do have an idea of what they want to do with their lives, but many do not.

Many adolescents are looking for some stable ground and a sense of direction. Sparking curiosity and getting ideas flowing at such an impressionable age is important for fostering growth, inspiring ambition, and brain development.

There is an adage, “You don’t know what you don’t know” and I will add: until you learn from experience or until someone teaches you. I am grateful to have been a part of both!

FROM EMILEE BRNUSAK

After going to Maclaren I came out amazed by the experience.

The kids were lovely. They were engaged in conversations about the brain, fun and upbeat and loved hearing me sing for them. Getting to sing to these kids was the highlight of this trip for me because I felt I was able to connect through emotion and music. After singing I even had one young person run back into the room to tell me how much they enjoyed my performance. This meant a lot to me, because these youth do not always get to communicate through other mediums like art or music very frequently.

Wolf (Emilee Brnusak) performs at NogginFest 2023

I am also currently working on my honors thesis at Portland State University which is centered around kids in youth facilities and their attachment injuries. Getting to go to Maclaren engaging with youth one on one really helped better inform my research. I was able to learn at least a bit about their backgrounds, hopes and struggles which I will carry with me when writing my thesis.

LEARN MORE: Trauma History and PTSD Symptoms in Juvenile Offenders on Probation

LEARN MORE: Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: A systematic review

Overall, I SUPER enjoyed this experience. Connecting to kids who look like me and have similar struggles to mine was an honor and I look forward to doing more work with youth at MacLaren in the future.

Many thanks

Huge thanks to the young people at MacLaren for their curiosity and questions, and to Vanessa Bucio, the Project Coordinator at HOPE Partnership, and all the welcoming staff at MacLaren and the Oregon Youth Authority. We look forward to returning next spring!