Post by Mina Sattari, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University. Mina is a welcome and regular contributor to outreach visits through Northwest Noggin.

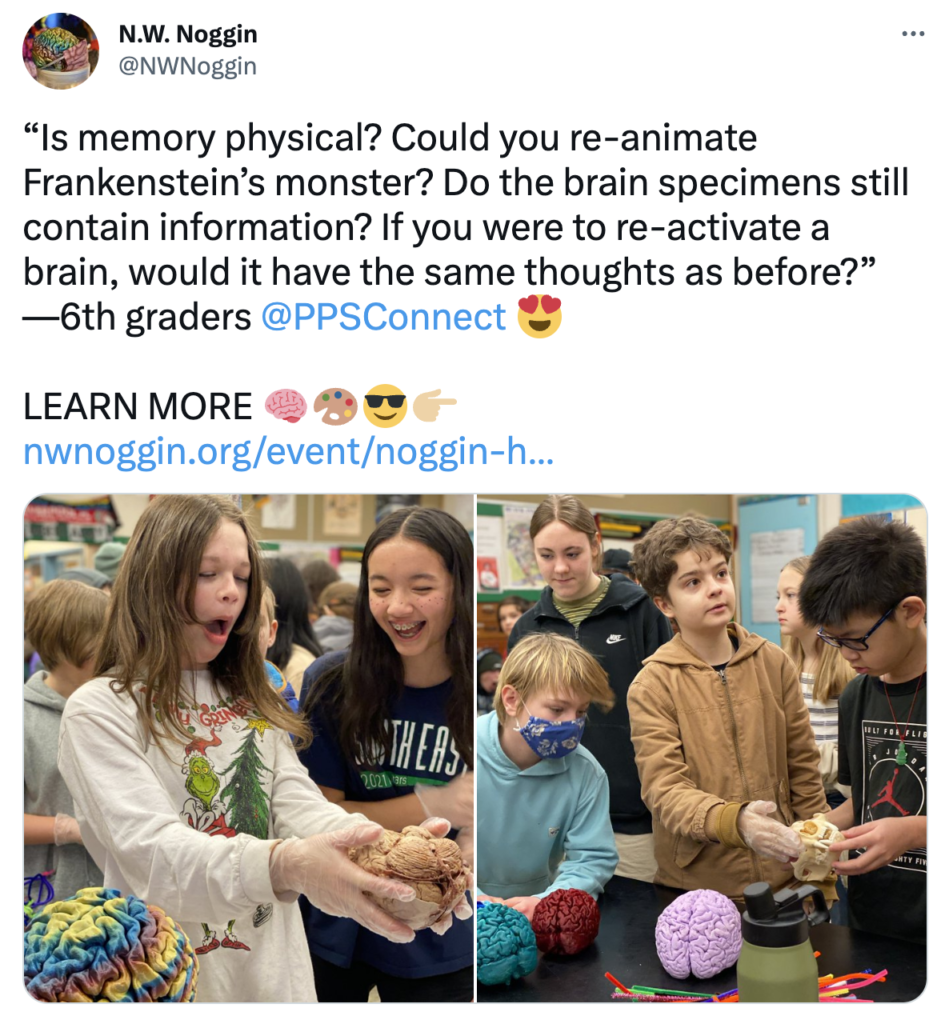

This winter I’ve had the pleasure of participating in outreach at Sacajawea Elementary School in Vancouver, Washington and at Leodis V. McDaniel High School, Hosford Middle School and Ron Russell Middle School in Portland, Oregon. All four visits offered wonderful insights into the thought processes and curiosity of young minds in Vancouver, Portland and David Douglas Public Schools.

LEARN MORE: How many neurons in a dinosaur brain?

LEARN MORE: Your Inner Worm Bin

LEARN MORE: Is memory physical?

LEARN MORE: When I Grow Up: Learning, Memory, and LTP

The Pause

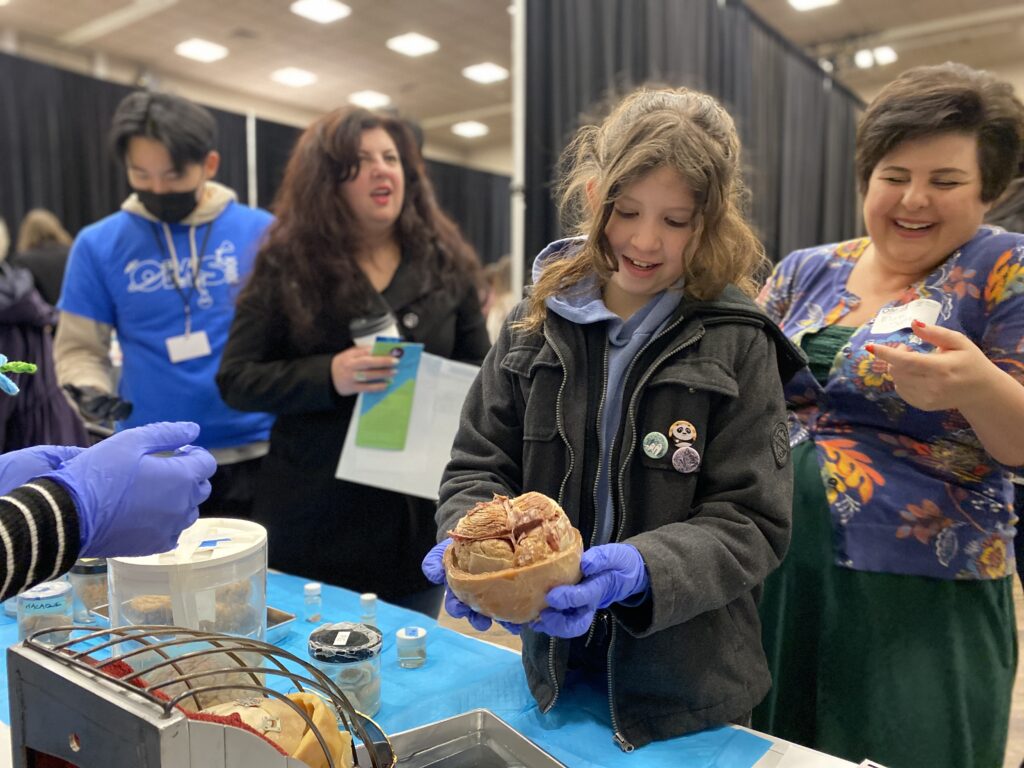

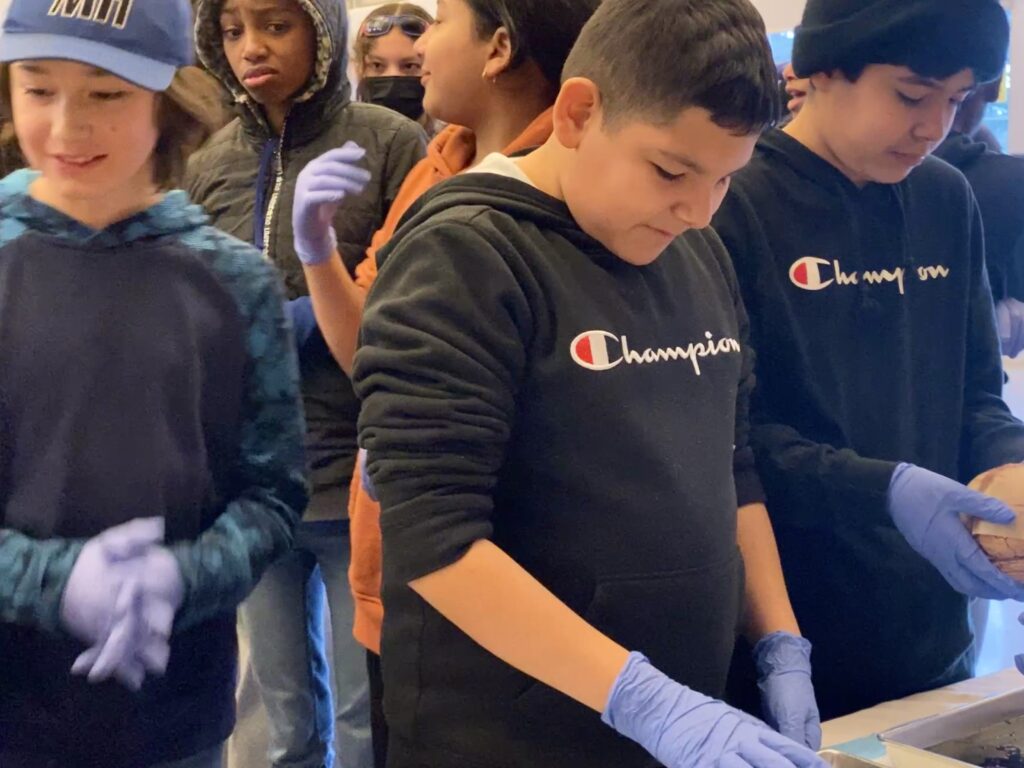

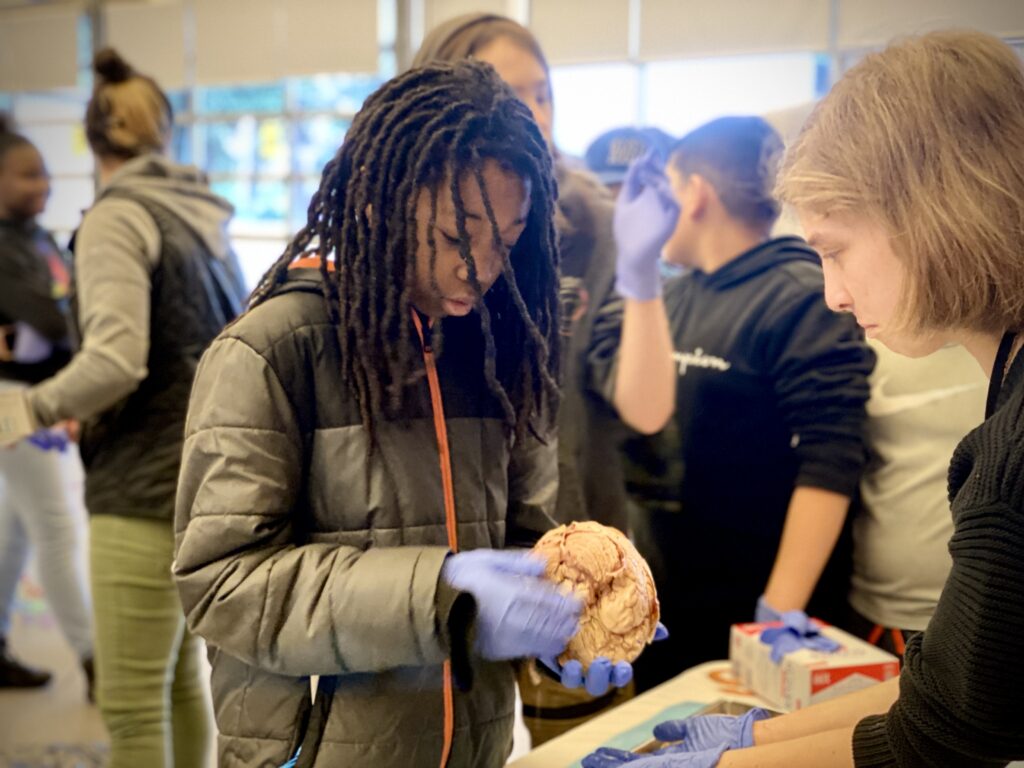

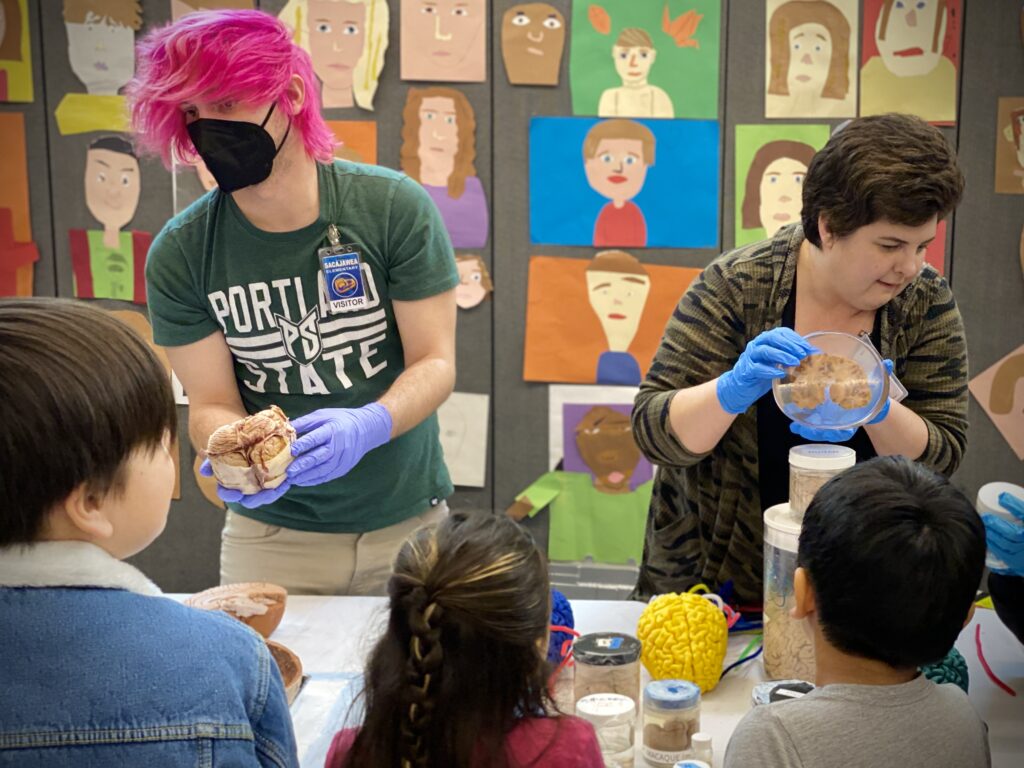

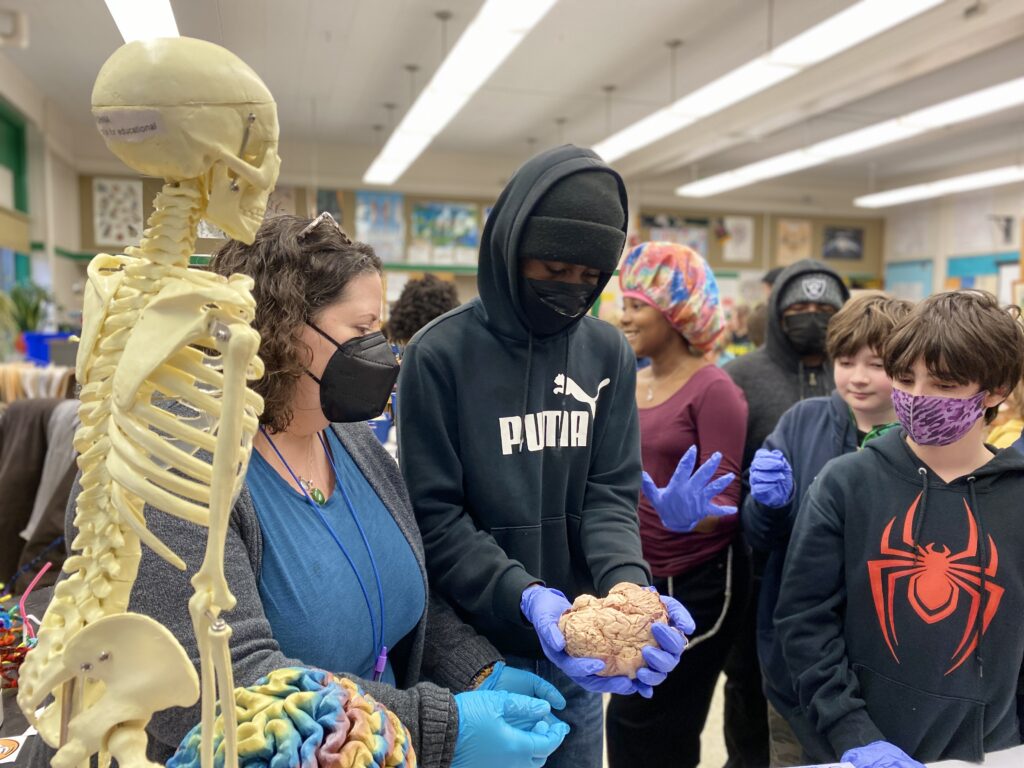

When we introduce Northwest Noggin to a rapt audience of students, there is a point where we tell them that we brought a real human brain specimen, one they can actually examine closely and even hold if they like.

There is always a pause, and the crowd is decorated with faces of excitement, dread, surprise and confusion as they process what they just heard.

This is clearly a powerful moment.

“My brain is still having trouble comprehending it held another brain. My brain is thinking about itself and about another brain in relation to each other.”

— Nina Knight

Nina Knight, at the time a teaching assistant at Stanford University, described how her own classroom brain wrangling experience had intense personal impact: “Another [classmate] was simply in awe of the ‘specimen’ before them. I, on the other hand, was having an existential crisis.”

LEARN MORE: Holding a human brain

LEARN MORE: How science helped me overcome my fear of death

The Question

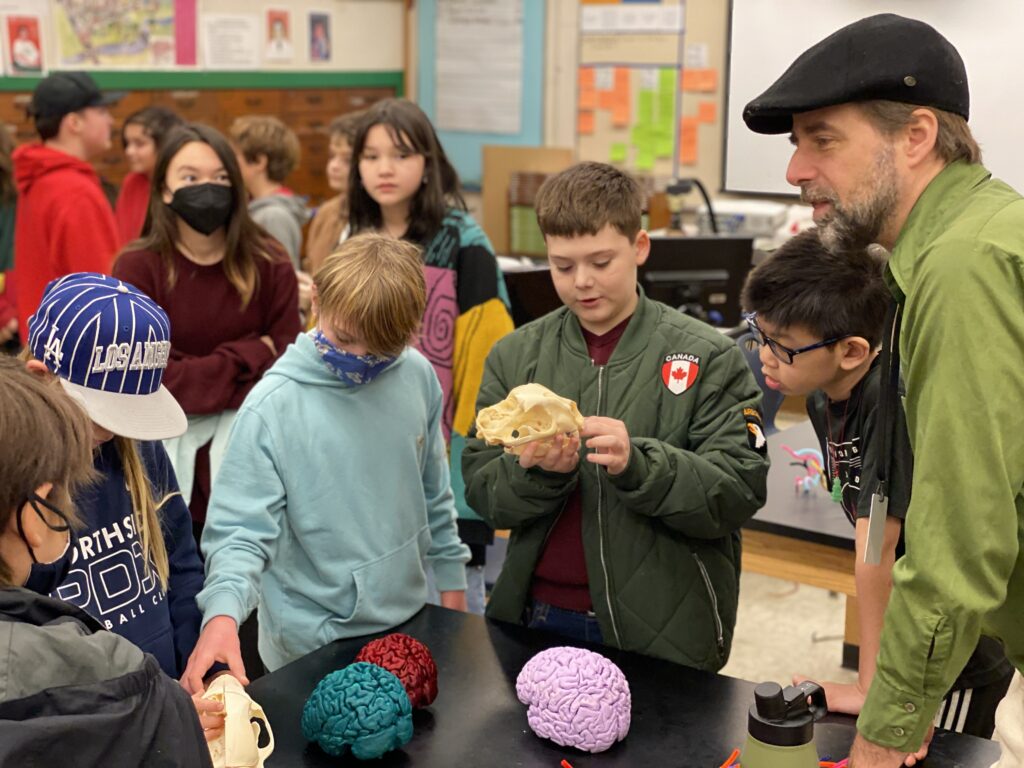

One brave soul will often ask THE question: “How did you get the brain?”

This question comes in many forms, revealing the depth of children’s imagination and wonder. “Did you murder someone?” they might ask. “Were they dead when you took their brain?” “How did you get the brain out of the skull?” and, “Do you know the person’s name?” It’s clear that people are processing their moral, ethical and social feelings about someone bringing in another person’s brain.

LEARN MORE: A Neurologist Looks at Mind and Brain: “The Enchanted Loom”

NOTE: The noggins we bring are donated (no murder involved), and we did not remove them ourselves.

LEARN MORE: A BioGift of Brains

The realization

I started to understand that behind the varied expressions were equally varied realizations.

There is, I believe, a general realization: that a living human being will someday become a dead body. Knowing that this brain on the table in front of you was another person changes your perspective, and confronts you directly with the reality of our existence. For example, at Hosford Middle School, I could see that students were fascinated by this awareness in an immediately accessible and even humorous way, excitedly asking questions about re-animating Frankenstein’s famous monster and perhaps accessing memories in a brain when it is no longer attached to a body.

LEARN MORE: Is memory physical?

Abstraction

Understanding the concept of death and what happens to the body after death is complex.

From a neuroscience and developmental psychology perspective, research shows that young children do not fully grasp the finality of death until they are at least around 6 or 7 years old. Understanding abstract concepts like permanence and irreversibility develops slowly in the brain, starting with none in babies, to fully grasping the often devastating loss of another human being.

LEARN MORE: Helping children understand death

LEARN MORE: Sources of children’s knowledge about death and dying

LEARN MORE: A New Instrument to Assess Children’s Understanding of Death

LEARN MORE: Children’s understanding of death: from biology to religion

Should I be ok with this?

From a social science perspective, the understanding of death and the body after death is influenced by different cultural and religious beliefs. Different cultures offer varied stories and explanations about what happens to the body after death, and engage in different practices including burial or cremation, and these beliefs and traditions can impact how children understand and process death.

LEARN MORE: Discussing Death with Children

LEARN MORE: A Child’s Concept of Death

LEARN MORE: Can you be an organ donor and donate your body to science?

The social science perspective

Understanding that a brain came from a dead person can be a challenging ethical dilemma for students. It might evoke strong emotional responses and raise uncomfortable questions about mortality and death. When I witnessed both the concern and excitement of seeing, touching, and being near a brain that was no longer attached to a person, I knew that an explanation was required.

Many students are aware of organ and body donation, but being so directly confronted with its reality contributes to “the pause” I witnessed and encourages deeper thought about something they may have only briefly considered before.

The neuroscience and arts perspective

“Neuroscience is by far the most exciting branch of science because the brain is the most fascinating object in the universe. Every human brain is different – the brain makes each human unique and defines who he or she is.”

— Stanley Prusiner

One way we’ve explored this topic is by explaining organ donation, beginning with facts that are age appropriate. For example, we understand that everybody dies. We often let that lead into a discussion of how some people choose to donate their bodies for medicine and research. Organ donation sometimes means quickly saving another life but it can also mean that doctors are able to practice surgery on a donated body, while scientists can learn, explore and understand more about who we are.

LEARN MORE: A Child’s Concept of Death

LEARN MORE: “What do we tell the children?”

LEARN MORE: Talking With Children About Organ/Tissue Donation

LEARN MORE: Organ Donation: Pass it On

LEARN MORE: Why people donate their brain to science

LEARN MORE: Brain Donation: A Gift for Future Generations

LEARN MORE: 10 tips on working with human body donors in medical training and research

LEARN MORE: Human body donation: How informed are the donors?

For example, we discuss how studying brains and bodies helps scientists understand diseases, and develop more effective therapeutic approaches to help the living. In the case of outreach and education, brains can inspire others to ask their own questions, lead to knowledge about further education and career opportunities and deepen understanding of neuroscience and research.

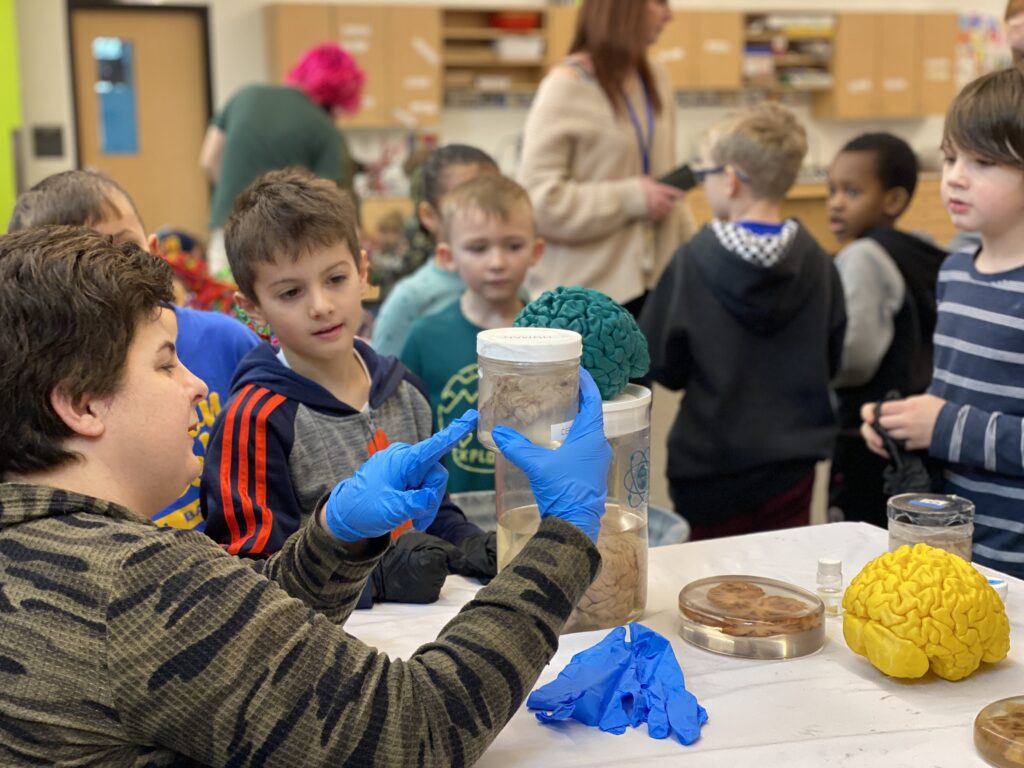

After going places with Northwest Noggin I strongly believe that the neuroscience perspective is a genuine and authentic way to approach the realization that we all have a brain, and a body. There was always palpable surprise, curiosity, attention, involvement and a flood of insightful questions.

“No one ever told me that I was made of something physical, something that was growing and changing in response to my experiences. That was a powerful moment, and for me, an inspiring realization.”

— Bill Griesar, NW Noggin

We also made brain cells from pipe cleaners, and sometimes printed them with ink, and the chance to make art led to more reflection, discussion and questions about who we are and how we function.

It was amazing to see this happening for the first time with many students I met this year.

LEARN MORE: Pipe Cleaner Brain Cells!

LEARN MORE: Brain Cell Gel Prints

I witnessed so much more than youth engaging with neuroscience.

Watching students process their emotions and wrestle with concepts about life and the brain was a beautiful experience. It showed me the power of outreach and how awareness about our minds and bodies might genuinely help us all.