Post by Anna Traylor, an elementary school educator pursuing a minor in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience as an undergraduate in Psychology at Portland State University.

Pandemic closures

My return to Portland State University in 2020 coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and what turned out to be the ever-extending COVID- 19 closures.

LEARN MORE: Crafting Coronavirus

Like many other college students (and teachers), this meant my school experience was fundamentally different from my past schooling experiences, and expectations I had about what returning to college would look like were immediately challenged.

LEARN MORE: School closures and reopenings during the COVID-19 pandemic

Outreach brings us together

Participating in outreach with NW Noggin brought me a small sense of community in my final college years. In a larger sense, visiting K-12 classrooms, residential drug treatment facilities, art galleries and houseless youth nonprofits reminded me how important it is to interact, learn from and care for each other.

LEARN MORE: Noggin Bloggin

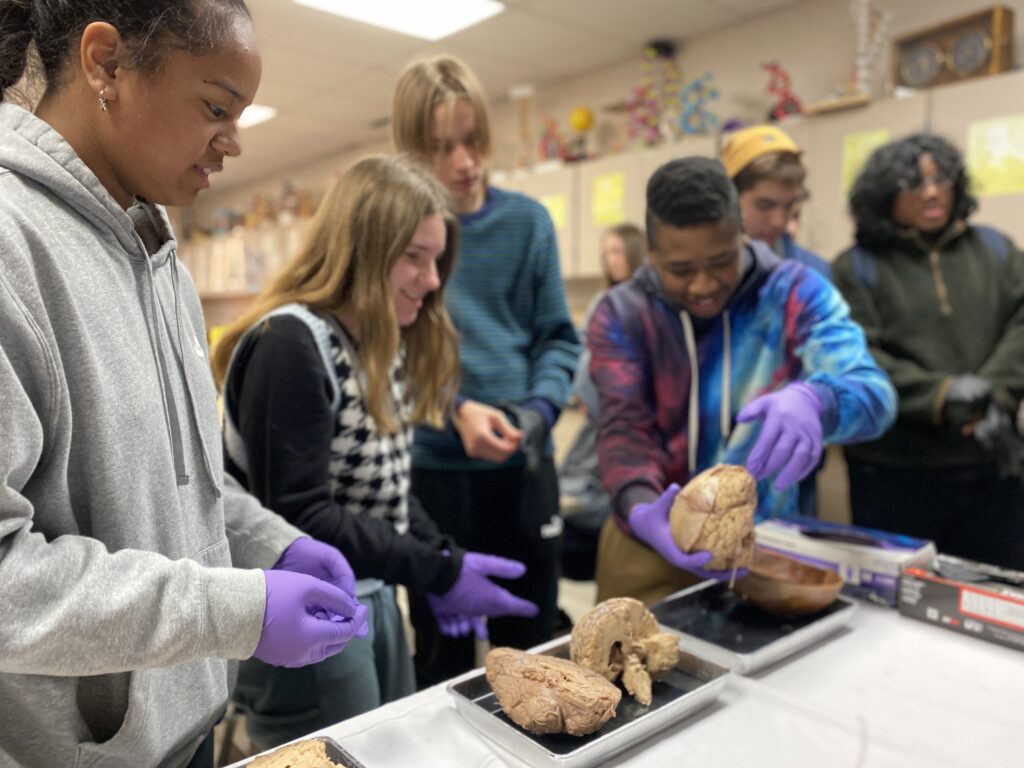

Visiting a classroom as a substitute or teacher’s aide is always fun. It was even more fun to visit a classroom with brains!

The students were engaged by the sheer novelty of having brains outside of bodies. From our mad scientist jars of cougar, macaque, and ferret brains to the human brains students (and teachers) could touch and hold, they were excited to learn and interact with us.

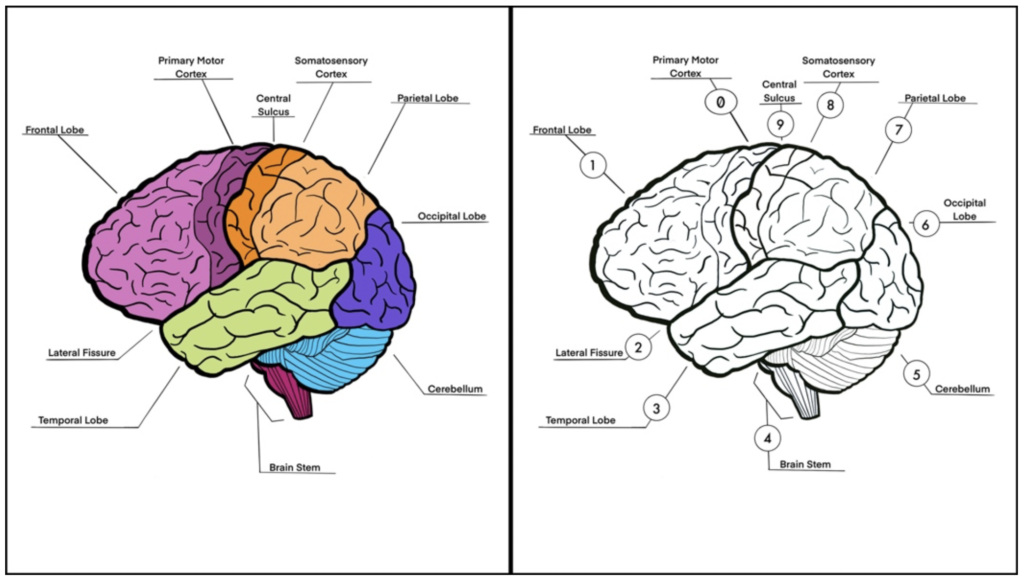

Engaging with the basics: Brain BINGO!

As a former teacher, I know how much work educators put into trying to create engaging activities for our students. So when I started volunteering with NW Noggin, I thought about how a class might prepare for a NW Noggin visit.

I also wondered how introducing some brain basics could plant seeds of neuroscience excitement in students. Since working with younger students is my forte, games, like bingo, seemed like the obvious winner when it came to introducing students to some brain basics. I created a few cards:

BRAIN BINGO Instructions:

Brain Stories

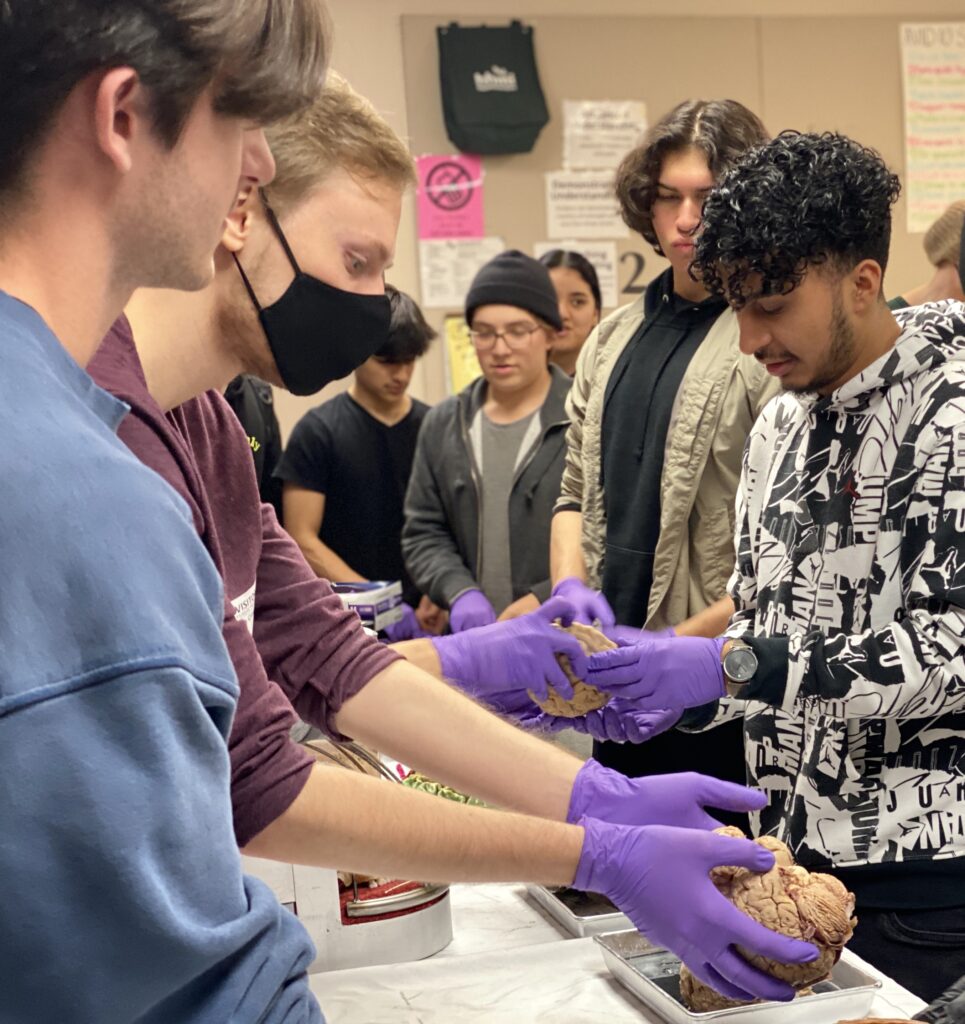

However, nothing came to mind on how to engage high school students in an introduction to neuroscience. Yes, we could use bingo, but I feared their cooler-than-thou attitude might stifle the playful learning game. While at Fort Vancouver High School I wanted to see how the students engaged with the opportunities to create prints and touch brains.

I was amazed by how students who might have zero interest in touching the brains still engaged in the experience through a kind of storytelling.

“We are the storytelling animal.”

— Salman Rushdie

Some students brought up philosophical questions such as, would they ever eat a brain or could they be friends with someone who had eaten a brain? They proposed multiple scenarios in which someone might eat a brain out of necessity, for example, or as a delicacy, or a joke – or if their perspectives might change based on who was eating the brains (e.g., parent, friend, or their teacher James).

Others wanted to know how Northwest Noggin had procured these brains, and many wanted to know about the people the brains belonged to. The statement “I was reminded about the human side to the science I read every day” from Jean Zarate, an editor at Nature Neuroscience, resonated with my experience with the storytelling students.

LEARN MORE: A BioGift of Brains

They made quick work of creating their short tales!

In one story, after a young man had fallen, we immediately snatched him up to harvest his brain to study any possible brain damage that had occurred. In another story, a student surmised that we must have concocted a very elaborate scheme to kidnap a granny right off the sidewalk with the intention of stealing her brain for scientific experiments!

LEARN MORE: Dialogues: The Science and Power of Storytelling

Their dramatic scenarios sparked my interest in how to engage high schoolers in some brain basics. I couldn’t help but sit down and prompt them to expand their stories about where they thought the brains were kept while not in use or how did they think the brains felt traveling overland to San Diego last week for the Society for Neuroscience conference.

LEARN MORE: Observing Art & Brains @ SfN

LEARN MORE: Brains Beyond SfN

I later learned that their innovative and compelling musings could be called micro-stories. These short, to-the-point stories are easily incorporated into a class and have been shown to help with information retention by capitalizing on our ability to empathize.

LEARN MORE: Leveraging Micro-Stories to Build Engagement, Inclusion, and Neural Networking in Immunology Education

LEARN MORE: The Storytelling Brain: How Neuroscience Stories Help Bridge the Gap between Research and Society

I feel honored to have learned about possible engagement strategies from the students at Fort Vancouver. By interacting with the brains present, the students taught me how to better interact and engage with brains in the future.