“We have a tendency sometimes to almost take for granted or think it’s normal” that so many young people have been locked up. “It’s not normal,” he said. “It’s not what happens in other countries. What is normal is teenagers doing stupid things. What is normal is young people making mistakes.” -Barack Obama after visiting El Reno federal prison in Oklahoma, as reported by The New York Times.

LEARN MORE: Obama, in Oklahoma, Takes Reform Message to the Prison Cell Block

In this post, you will find…

- Teenagers are not adults

- Trauma impacts brains

- Oregon voters passed Measure 11 in 1994

- Racial disparities in Measure 11 are stark

- Trump DOJ flies blind

- Noggins and HOPE

- “Where are Latinos?” -Tyler Braly (PSU)

- Your brain is electric -Jordan Ray (PSU

- Faces of races -Binyam Nardos (OHSU)

- “I-Thou”: Labeling and language -Taylor Stewart (UP)

NOTE: We return to MacLaren on January 23, 2019!

LEARN MORE: Noggin @ MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility

Teenagers are not adults. A 15, 16 or 17 year old – and even those years older – are undergoing dramatic, consequential changes in brain anatomy and function, responding to diverse environments and making lots of mistakes. All of us make mistakes. How others respond to inevitable youth errors – some minor, some devastating – impacts development, and can benefit or undermine the trajectory of promising young lives.

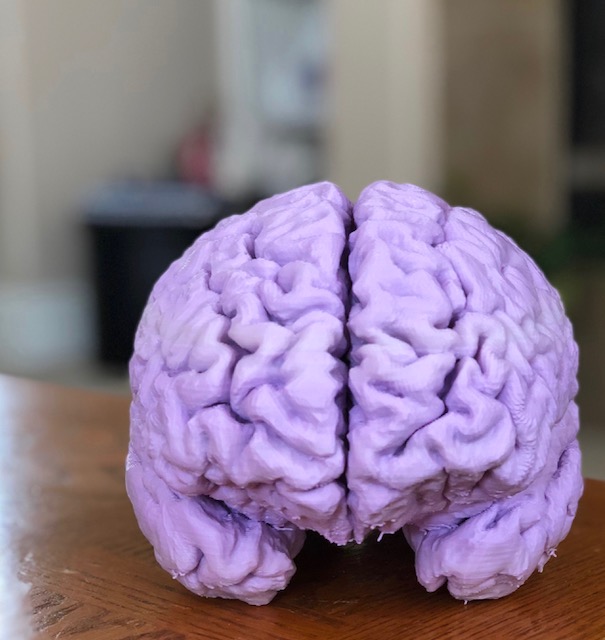

3D printed brain based on an MRI of an Oregon teenager: “The adolescent brain is structurally and functionally vulnerable to environmental stress, risky behavior, drug addiction, impaired driving, and unprotected sex…” –Mariam Arain et al

LEARN MORE: Maturation of the adolescent brain

LEARN MORE: Adolescent Risk Taking, Impulsivity, and Brain Development: Implications for Prevention

LEARN MORE: NIH releases first dataset from unprecedented study of adolescent brain development

LEARN MORE: The Teen Brain: 6 Things to Know

LEARN MORE: Dancing, Parkinson’s & Mistakes

Accountability and consequences are important. Consequences offer feedback with emotional significance, and drive critical, necessary changes in neuronal connectivity and behavior. During adolescence, networks of brain regions that permit sustained and directed attention, reflection and rumination, the informed consideration of risks – and the ability to inhibit inappropriate behavior (depending on the context, and social rules) are all developing, and both mistakes and their consequences help force necessary change and maturation of the brain…

“Because the brain is undergoing such rapid, fundamental changes at this stage of life, adolescents have a heightened capacity to learn and to [grow] out of risky behavior. Given an environment and supports appropriate to their developmental stage, most young offenders have the potentialto become law-abiding adults.” — The MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience

The social rules we’re expected to learn during adolescence are complicated. They depend on who you are, and who you’re with, and also your race, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, class status, language, neighborhood, national origin, height, weight, and a host of other individual factors. Learning to “code switch” depending on the social context is a challenge for the developing brains of teenagers – particularly neural networks in their malleable frontal lobes.

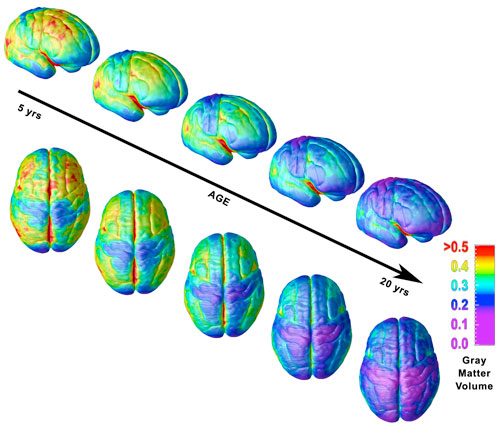

IMAGE: It may seem counter-intuitive, but the volume of “gray matter” (i.e., the number of neurons, and number of synaptic connections) actually drops in the frontal lobes during adolescence, as our neural wiring grows more specialized and efficient for the activities and behaviors we pursue…and are able to prevent.

LEARN MORE: The Adolescent Brain

LEARN MORE: Frontal Lobe GABA Levels during Adolescence: Associations with Impulsivity and Response Inhibition

LEARN MORE: Connectivity Gradients Between Default Mode & Attention Control Networks

LEARN MORE: How Code-Switching Explains The World

A recent study of new teachers heading to public schools found that a neutral emotional expression on white male faces was perceived as neutral, while the same expression on young black faces came across as angry.

How does that affect a child’s social experience, how they are treated, and the expectations they develop, or the consequences they face? How does this impact their brains?

LEARN MORE: Preservice teachers’ racialized emotion recognition, anger bias, and hostility attributions

LEARN MORE: Prospective Teachers More Likely to View Black Faces Than White Faces as Angry

LEARN MORE: Neighborhood effects on use of African-American Vernacular English

LEARN MORE: To Educate or To Incarcerate: Factors in Disproportionality in School Discipline

LEARN MORE: Closing the Racial Discipline Gap in Classrooms by Changing Teacher Practice

LEARN MORE: Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Differences in School Discipline among U.S. High School Students: 1991-2005

LEARN MORE: School Opportunity Hoarding? Racial Segregation and Access to High Growth Schools

Research also highlights the significant ethnic and income differences in youth (and lifetime) experiences of trauma. Black and Hispanic participants report more traumatic events (“polyvictimization”) compared to non-Hispanic Whites. In addition, many young Northwesterners lack the resources (including legal, educational, health care/mental health,…) available to those from more privileged, higher income backgrounds…

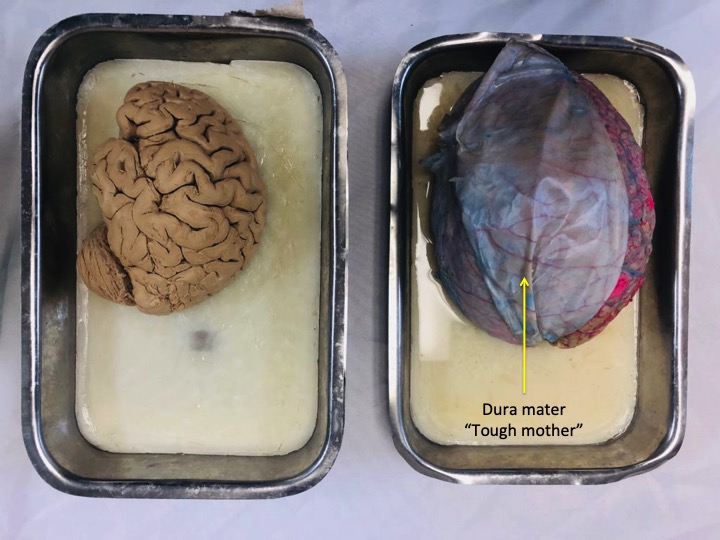

Rubylith brain and painting by Joshua Abraham. For more from Joshua and Eileen Torres on how stress affects the brain, see Feeling stressed? a Noggin presentation at Velo Cult.

LEARN MORE: Polyvictimization, Income, and Ethnic Differences in Trauma-Related Mental Health During Adolescence

LEARN MORE: Polyvictimization: Latent profiles and mental health outcomes in a clinical sample of adolescents

LEARN MORE: Childhood adversity and the continued exposure to trauma and violence among adolescent gang members

LGBTQA+ youth are also selectively traumatized, victimized, and criminalized in the United States.Youth may be rejected by their families, demonized and/or abused by religious organizations, and are more likely to be homeless. “These youth, particularly gay and bisexual boys, report higher rates of sexual victimization compared to their heterosexual peers. Sexual minority youth…were also 2-3 times more likely than heterosexual youth to report prior episodes of detention lasting a year or more.” Many of these young people remain largely invisible, fearful of identifying themselves or discussing their experiences with those in the criminal justice system.

Carla Rossi, ME, MYSELF & IT@Littman Gallery, Portland State University

LEARN MORE: Disproportionality and Disparities among Sexual Minority Youth in Custody

LEARN MORE: UNJUST: HOW THE BROKEN CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM FAILS LGBT PEOPLE OF COLOR

LEARN MORE: The Unfair Criminalization of Gay and Transgender Youth

LEARN MORE: The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents

LEARN MORE: Religious Conflict, Sexual Identity, and Suicidal Behaviors among LGBT Young Adults

LEARN MORE: State Settles MacLaren Sex Abuse Cases

HOW TO HELP: The Trevor Project (Saving Young LGBTQ Lives)

Yet in 1994, Oregon voters passed Oregon Ballot Measure 11, a law that established mandatory minimum sentences for “serious crimes against persons” and required defendants aged 15 and older to be tried as adults. Most decision making power now rests in the hands of prosecutors, who are often rewarded for tackling more cases, gaining more convictions, and imposing longer sentences, while judges in Measure 11 cases have limited discretion in how sentences are handled. Measure 11 also mandates exceedingly high bail amounts (typically $250,000). According to Multnomah County, “any person charged with a Measure 11 crime is usually held in custody until the court process is complete.”

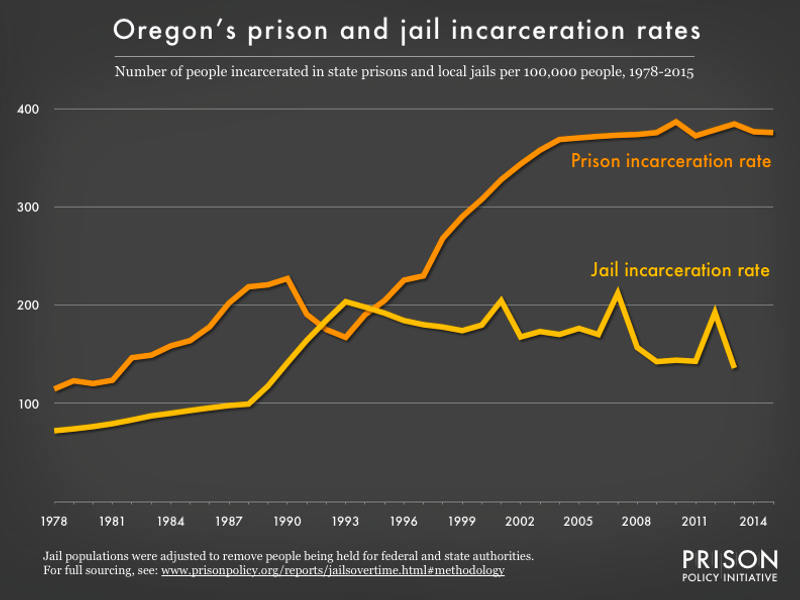

Oregon’s prison and jail incarceration rates, 1978 – 2015 (Prison Policy Initiative)

LEARN MORE: What is Measure 11?

LEARN MORE: What happens if my child is arrested for a Measure 11 crime?

LEARN MORE: The prosecutor: the most powerful person in the room

LEARN MORE: To Blame or to Forgive? Reconciling Punishment and Forgiveness in Criminal Justice

Some prosecutors and district attorneys have argued that Measure 11 is an unqualified public good.The crimes involved are those “against persons,” and have traumatic, potentially catastrophic effects on the lives of victims and their families. According to a 2011 op-ed by retiring Clatsop County DA Josh Marquis, “Oregonians want there to be truth in sentencing,” and “Measure 11 offenses include the higher degrees of homicide…and more serious sex felonies such as rape and child molestation.” Others, including Multnomah County DA Rod Underhill, claim to have altered their approach after backlash following high profile sentencing of young teenagers in Portland.

LEARN MORE: Debunking myths about Measure 11

LEARN MORE: The only way to tackle mass incarceration is to address the issue of those convicted of violent offenses

LEARN MORE: District attorney adopts new Measure 11, juvenile policy

Yet Oregon now has one of the highest youth incarceration rates in the country. Many young Oregon teens take questionable plea deals to avoid the more excessive outcomes threatened by prosecuting authorities.

LEARN MORE: Oregon Incarcerates Youth At Higher Rate Than Most States

LEARN MORE: Report blasts Measure 11’s ‘harsh sentences’ for Oregon youths

LEARN MORE: Red Justice in a Blue State

LEARN MORE: America’s Justice System Has the Wrong Goals

LEARN MORE: Youths branded by Measure 11

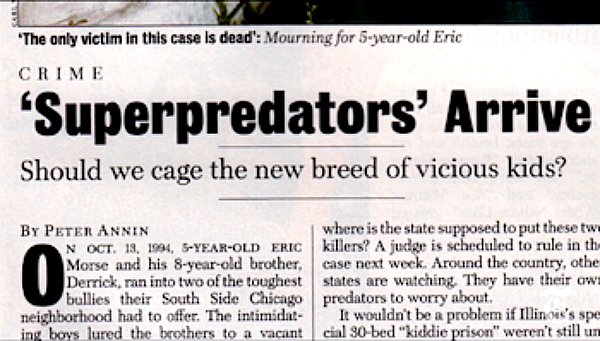

Measure 11 passed during a decade of acknowledged media sensationalism over high profile crimes by minority youth. John J. DiIulio Jr. at Princeton (now at the University of Pennsylvania), who went on to lead the newly established White House Office of ‘Faith-Based’ Initiatives during the George W. Bush administration, infamously wrote (along with two co-authors), “…here is what we believe: America is now home to thickening ranks of juvenile ‘superpredators‘ – radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters, including ever more preteenage boys, who murder, assault, rape, rob, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, join gun-toting gangs and create serious communal disorders.” Hillary Clinton also used the term superpredator to tout President Bill Clinton’s signing of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, during a 1996 speech in New Hampshire.

Newsweek, 1/22/96 (via Poynter)

LEARN MORE: Superscapegoating – Teen ‘superpredators’ hype set stage for draconian legislation

LEARN MORE: When Youth Violence Spurred ‘Superpredator’ Fear

LEARN MORE: As Ex-Theorist on Young ‘Superpredators,’ Bush Aide Has Regrets

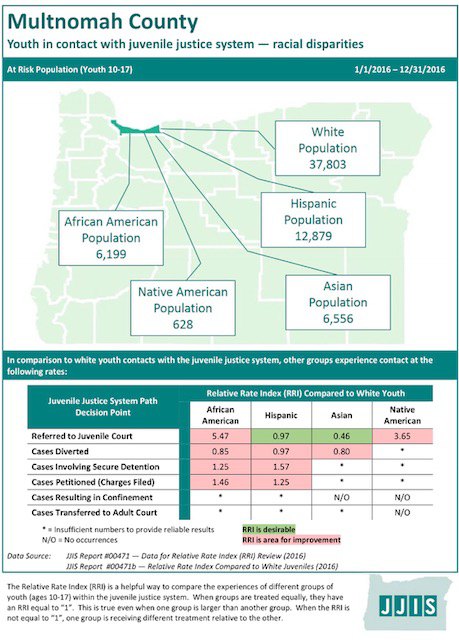

The racial disparities in the application of Measure 11 are stark.The Relative Rate Index (RRI) is a proportional measure used by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention to compare “rates of juvenile justice contact experienced by different groups of youth,” including white young people and youth of color (specifically, African American, Asian American, Native American, and Hispanic).

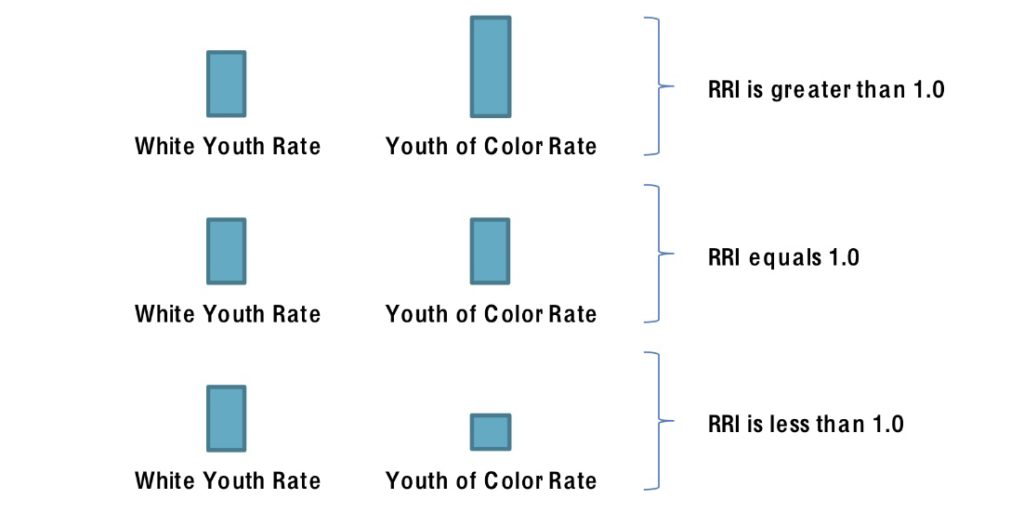

Racial and Ethnic Disparities: If groups being compared are treated equally, the RRI is 1.0. Higher and lower RRI values indicate differences in treatment by the juvenile justice system.

LEARN MORE: What is an RRI?

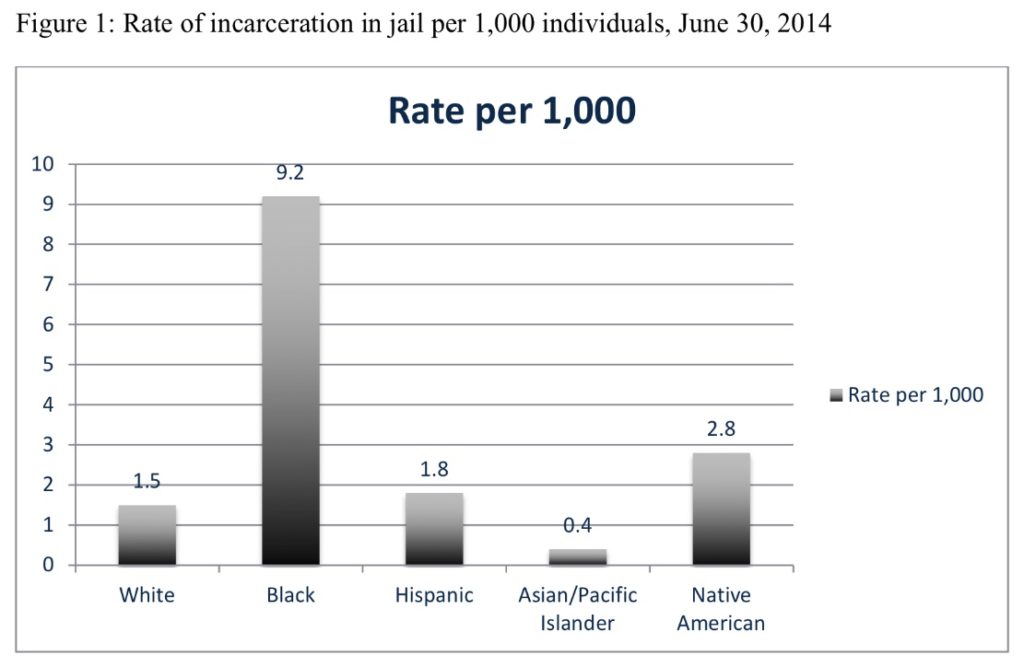

Native American, Hispanic and particularly Black Oregonians are incarcerated at disproportionately higher rates relative to white people. This is reflected in RRI values that are often well above 1.0 (e.g., a value of 5.47 for African Americans in Multnomah County during 2016).

FROM: Racial & Ethnic Disparities Relative Rate Index Multnomah County (2016)

FROM Multnomah Country, OR: Racial and Ethnic Disparities and the Relative Rate Index (RRI)

“Minority youth [in Oregon]…have higher rates of involvement in the juvenile system than their white counterparts and receive more intensive and intrusive dispositions, including higher rates of detention, lower rates of diversion, higher rates of placement in correctional facilities, and higher rates of transfer to adult court.” — Dr. William Feyerherm

LEARN MORE: Youth and Measure 11 in Oregon

LEARN MORE: Over- Representation of Minority Youth in Oregon’s Juvenile Justice System

LEARN MORE: Prisons of Poverty – Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned

LEARN MORE: Race, Bias & Brain: You Can’t Control Art

LEARN MORE: The insidiousness of unconscious bias in schools

LEARN MORE: Are “Stand Your Ground” Laws Racist and Sexist? A Statistical Analysis of Cases in Florida, 2005–2013

Statue by Ronald S. McDowell, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama

“Who’s they?

that’s interesting,…

Even the times that I have been arrested

they always make comments

about God, you look like Mr.,

uh,

all-American white boy.

That has actually been said to me

by a…by a

cop…

I remember being arrested in Santa Barbara one time

and

driving back

in the cop car

and having a conversation about tennis

with the cops.

So,

ah,

I’m sure I’m seen by the police totally different

than a black man.”

-Excerpts from “They,” Anna Devere Smith in Twilight Los Angeles 1992

Infuriatingly, the recently appointed director of the DOJ Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention has moved to **cut** data reporting requirements for states, including several Southern states which have repeatedly failed to provide the relevant statistics. Regarding the relevance of neuroscience research, Director Caren Harp has stated that “I would have to see the scientists…on the witness stand being questioned and seeing if their science meets the minimum standard for admissibility in a court of law.” She also suggests that “Scripture provides a wealth of guidance for criminal law.” Harp is an Arkansas prosecutor and a former law professor at the evangelical Liberty University.

LEARN MORE: OJJDP Head Caren Harp Wants to Rebalance System From Focus on ‘Therapeutic Intervention’

LEARN MORE: ‘Marshall Project’ Report Highlights Racial Gap In Juvenile Detention Centers

LEARN MORE: This Agency Tried to Fix the Race Gap in Juvenile Justice. Then Came Trump

LEARN MORE: Juvenile Injustice: OJJDP Dismantles Protections for Youth of Color in the Justice System

LEARN MORE: Do Moral Communities Play a Role in Criminal Sentencing? Evidence From Pennsylvania

LEARN MORE: Crime and punishment and rehabilitation: a smarter approach

LEARN MORE: How Liberty University Built a Billion-Dollar Empire Online

In addition, neuroimaging research reveals that recognition of people belonging to “extreme out-groups” (e.g., incarcerated youth, and the homeless) may be processed in the brain differently than those from “in-groups.” Brains of some subjects respond to images of those without homes, for example, as if they were potentially non-human “objects of disgust” rather than fellow human beings (e.g., Harris & Fiske, 2006). Epithets like ‘superpredator,’ or the venomous language of President Donald Trump towards Mexican immigrants (e.g., “These aren’t people. These are animals.“) encourage what is known as ‘dehumanized perception,’ and this failure to appreciate other people as people may have severe consequences for societal health.

LEARN MORE: Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups

LEARN MORE: Not yet human: implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences

LEARN MORE: The Roles of Dehumanization and Moral Outrage in Retributive Justice

LEARN MORE: Dehumanized Perception: A Psychological Means to Facilitate Atrocities, Torture, and Genocide?

LEARN MORE: A hypothetical neurological association between dehumanization and human rights abuses

LEARN MORE: Landscapes of the Brain: Seeing us all through research & art

The experience of dehumanization, racial and other bias, punitive “spare the rod, spoil the child” religious opprobrium and stress, in combination with the variability of growing brains and brain networks involved in social decision making during adolescence (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008), can create an environment that is hostile to healthy brain development.

There are kids in here…

Perception: From Prison To Purpose | Trailer from Perception Doc on Vimeo.

“Adversity is our biggest asset. Once you understand that, you have taken your power back.” -Noah Schultz

LEARN MORE: Noah Schultz: Incarcerated at 17, writer and poet at 18, TEDx speaker at 23

This week we returned to the city of Woodburn, Oregon, to visit with close to 100 incarcerated young people at the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, where over 200 boys and young men (ages 12 – 25) are currently confined. MacLaren is administered by the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), a state agency with a mission “to protect the public and reduce crime by holding youth accountable and providing opportunities for reformation in safe environments.”

“You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them” –Maya Angelou

The Hope Partnership, a collaboration between OYA and Janus Youth Programs, provides classes and community networking opportunities for young people to help build self-confidence and the skills needed to transform their lives. HOPE has arranged for multiple artists, musicians, activists, tradespeople – and now neuroscience outreach volunteers – to visit with, listen to, and enrich the experiences of incarcerated youth at MacLaren.

“That’s what Hope Partnership is. It builds connections.” –Kathleen Fullerton

Kathleen Fullerton is the Program Coordinator for HOPE. We’d met with her and MacLaren youth leaders earlier this summer, and were invited back after an initial discussion of bias in judicial and law enforcement systems, pathways in psychology for counseling and research, and what role neuroscientists play, or might play, in judicial and legislative reform.

LEARN MORE: Correctional Connections

LEARN MORE: Hope Partnership unlocks a future for incarcerated youths

LEARN MORE: Hope Partnership Celebrates its Fifth Year Anniversary

LEARN MORE: Janus Youth Programs – Residential & Re-Entry Services

LEARN MORE: HOPE Partnership – Janus Youth Programs

This time we gathered a larger group of interested graduates and undergraduates in neuroscience, including Jordan Ray, Jade Osilla and Tyler Braly from Portland State University, Kayla Townsley from both PSU and Oregon Health & Science University, Eileen Torres, Binyam Nardos, Brittany Alperin, Jessica Patching-Bunch and Emma Schifsky from OHSU, Taylor Stewart from the University of Portland, and Elsa Gomez and Ruth Marigomen from WSU Vancouver...

We were there to discuss research, show brains, and answer questions. Young people at MacLaren are studying both the law and aspects of neuroscience (including adolescent brain development) that are relevant to how our justice system operates, in order to bolster a case for changes to Measure 11.

We spent over six hours with multiple groups of MacLaren youth, who asked some of the most insightful, informed, and challenging questions about anxiety, bias, mental illness, drugs, and development. Below are some thoughts from our outreach participants. More observations are coming soon…

“I think it’s important for us as a society to remember that the youth within juvenile justice systems are, most of the time, youths who simply haven’t had the right mentors and supporters around them – because of circumstances beyond their control.” –Q’orianka Kilcher

From Tyler Braly, Portland State University

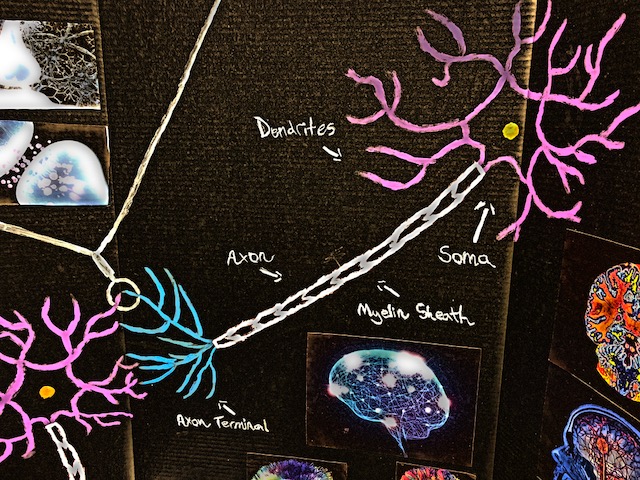

“I spent a lot of time with the brains talking about the anatomy of the neuron, cortical layers, and what different networks in your brain do. I got to show off a model of the newly discovered rose hip neuron made of pipe cleaners! At least a half dozen kids enjoyed making ‘This is your brain’ jokes on their friends using the chicken brains we brought.

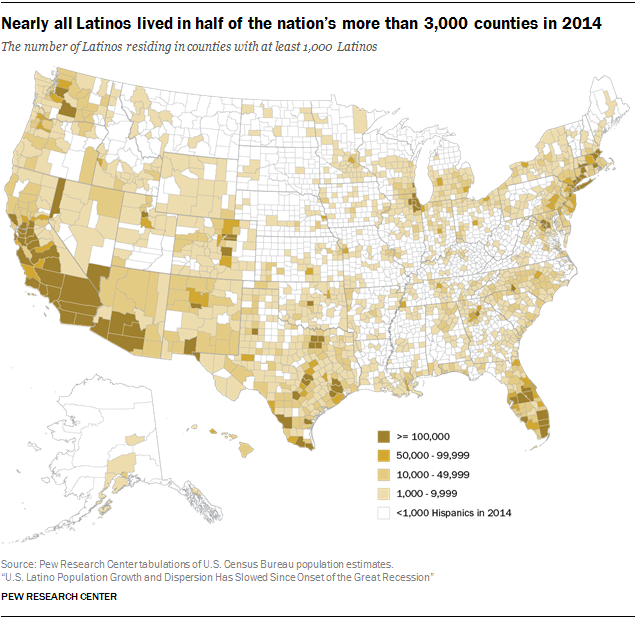

During a long discussion about implicit bias and representation, one boy asked where Latinos were in all these studies. Why was it only comparisons between white and black faces? What about people with mixed heritage and race?

LEARN MORE: Key facts about how the U.S. Hispanic population is changing

“Categorizing Hispanics as a minority group, becomes much more difficult once you realize this population is almost evenly divided between those who identify with the white majority and those that have trouble seeing themselves in any of the standard racial categories. It is not that some are more Hispanic or Latino than the others because they all have taken on that mantle. Nor are they saying that race does not matter to them. Rather, the message seems to be that Latinos in the United States experience race differently. For them, it is not something that pertains exclusively to skin color, let alone to history and heritage.” –Pew Research on Hispanic Trends

I agreed that Hispanics and Latinos were underrepresented in these studies, and pointed towards the complex ways in which ethnic identity is constructed within specific cultural contexts, and how this can change over time. Research often ignores this complexity, particularly with regards to Latino, Hispanic, and Chicanx identities.

LEARN MORE: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Research Studies: The Challenge of Creating More Diverse Cohorts

LEARN MORE: Underrepresentation of Hispanics and Other Minorities in Clinical Trials

LEARN MORE: Latino Beliefs about Biomedical Research Participation

LEARN MORE: Racial Identity and Racial Treatment of Mexican Americans

LEARN MORE: Shades of Belonging (Pew Research on Hispanic Trends)

LEARN MORE: Latino Network Learning & Lobes

We encouraged him, and others, to keep asking questions, and keep challenging researchers and research.”

From Jordan Ray, Portland State University

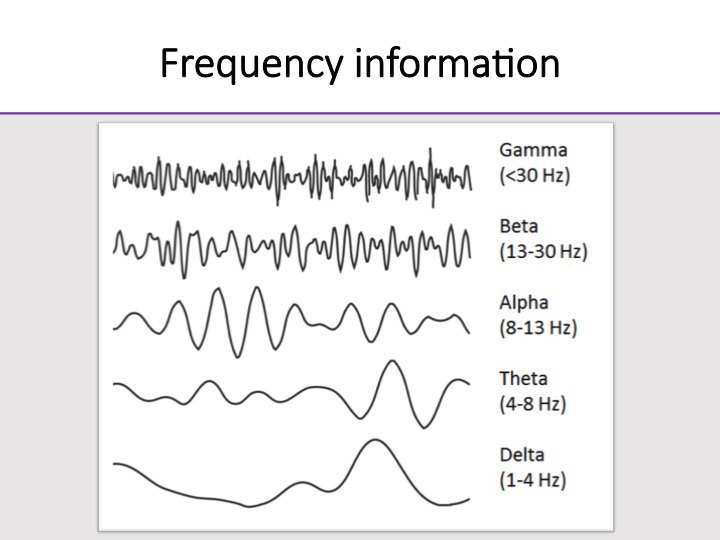

“I staffed an electrophysiology table, and we set out on an exploration of the brain’s electrical activity. Our brain cells utilize electric currents, which in aggregate can be detected in rhythmic activity through electrodes placed on the scalp…

LEARN MORE: Changing Brain Waves of Depression

By using a four-channel OpenBCI biosensing Ganglion Board, we were able to discover both electroencephalography (EEG, from the brain) and electromyogram (EMG, from muscle) signals and record them. For the first couple groups, I set up the equipment, but by the end of the visit, many participants were gelling and placing the electrodes, testing the impedances, and analyzing the signals: pretty impressive!

Here’s some of what we found:

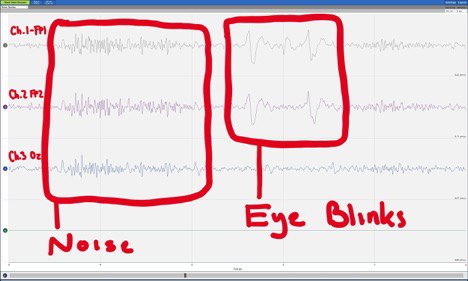

After ensuring impedances would be acceptable for recording, we decided to test the set up by looking at the difference between scrunching a forehead and blinking an eye. We found a clear difference between the two as shown here in Fig. 1:

Fig. 1: Differentiating signal noise from muscle tone vs eye blinks

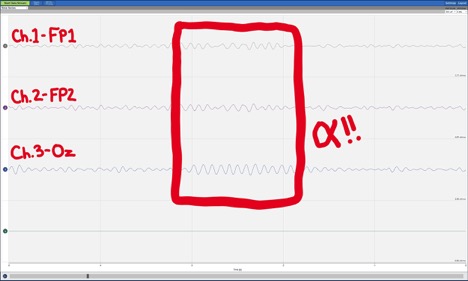

From here, we decided to test our meditation power by looking for alpha (wave activity after eyes closing. Alpha wave generation begins in the visual cortex, found in the occipital lobe. In Fig. 2, we can see alpha onset approx. 10 seconds after eye closure in not only the Oz (Occipital Zero) electrode, but also over Fp1/Fp2 (Frontal Pole 1 & 2). This participant was very good at focusing despite the noisy environment; very impressive!

Fig. 2: Alpha wave activity (7.5-12hz) over all three electrodes (FP = frontal pole; Oz = occipital lobe) approximately 10 seconds after eyes closed. This participant was able to focus in quite well, even in a pretty loud room…

LEARN MORE: Review of the Neural Oscillations Underlying Meditation

LEARN MORE: EEG Derived Neuronal Dynamics during Meditation: Progress & Challenges

LEARN MORE: Brains, biofeedback & SLEEP @ Fort Vancouver!

From Binyam Nardos, OHSU

Unofficial reports by some media outlets and community outreach organizations that track and document police violence demonstrate that more than any other demographic group, young black males are at a particularly heightened risk for fatal police encounters.

The underlying causes for the reported violent interactions between police and black individuals are likely multifactorial. To shed light on the issue, one approach taken by psychologists and neuroscientists has been to investigate potential behavioral and intrinsic brain-based biases when perceiving black vs. white faces. One notable study (B. Keith Payne, 2001) reports that brief presentation of black vs white faces as racial cues can actually “prime” a quicker response to weapons or items of danger. The same manipulation increases misidentification of tools as weapons for black, relative to white, face cues. This occurs even if the face cue was flashed so quickly that the participant doesn’t even know it was there.

Several parallel studies have been conducted to investigate the implications of these types of effects on ‘real world’ actions. These studies use virtual reality games that simulate the police officer’s dilemma of whether to shoot a suspect (criminal vs. innocent) who may be holding a (weapon vs. harmless object) (Correll, et al 2002; Correll et al., 2007; Greenwald et al, 2003). The findings from such studies are chilling, and indeed capture the chilling disparity with which people of color fall victim to fatal encounters with police, relative to their White counterparts. The noted studies show that participants are faster at shooting armed black targets than armed white targets, and faster at deciding not to shoot unarmed white targets relative to unarmed black targets. Similarly, participants show a greater tendency to shoot unarmed targets when those targets are black rather than white.

The above and similar findings point to race as an important construct that drives perception, which may, at least in part, drive the actions taken by law enforcement. Our research, funded by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscienceasks an additional question. Are these types of relationships dependent, or even enhanced, based on the emotional state of the subject making quick decisions?

To investigate the effects of race and emotional context on face perception, our study used black and white faces as stimuli in a functional MRI task (emotional go/no-go task) designed to study impulse control in black and white young adults. Three emotional contexts were induced in a group of African American and European American participants: rewarding, threatening, or neutral contexts. Behaviorally, regardless of their race, participants exhibited greater impulsive actions (more false alarms) to black faces. This response was enhanced in threat contexts.

The fusiform cortex is a region of the brain implicated in face perception. Studies show that this region of the brain has a greater neural response to faces of one’s own race relative to other-race faces (Gobly et al. 2001). In the current study, we hypothesized that emotional context would influence the relative neural activity to own- vs. cross-race faces in the fusiform cortex. Indeed, the functional MRI observations in the fusiform cortex suggest that context influences the functional responses to black vs. white faces, but interestingly, in a manner dependent on the race of the participant. African American participants exhibited similar responses across all contexts. Specifically, they exhibited higher activity for the same-race, i.e. black, relative to cross-race, i.e. white faces; as would be expected from previous studies. European American participants exhibited the expected pattern (higher activity for same-race, i.e. white, relative to cross-race, i.e. black faces) for the neutral and reward contexts, but not for the threat context. In the threat context, the pattern was reversed. Instead of responding with increased neural activity to members of the same race, European Americans demonstrated increased activity for black faces.

Our preliminary results demonstrate the importance of emotional context as an essential factor that influences impulsive decision making to racial cues, i.e. faces. Further investigations are underway to uncover the factors underlying the differential effect of context on African American vs. European American participants. The above described and similar investigations should assist in ongoing efforts to increase awareness of race disparities in law enforcement and ultimately a reduction in preventable violent encounters.

From Taylor Stewart, University of Portland

“The world is not comprehensible, but it is embraceable: through the embracing of one of its beings.” –Martin Buber

My name is Taylor Stewart and I am a Civil Rights Advocate and I graduated with a degree in Communication. This means that I don’t know much about the brain or neuroscience, but I know a few things about how we, as humans, use language to create, construct, and categorize our world. Thus, as the dissimilar personality in the group that visited MacLaren, I wanted to share the perspective of a Communication professional on the topic of the brain, bias, and branding.

To begin, the Framing Theory of Communication identifies the way with which individuals perceive the world. Analyzing these “frames” reduces the complexity as it’s through these frames that individuals interpret, construct, and reconstruct their reality. How an individual frames their reality, their self-perception, and the “others” in their reality will directly affect how they make attributions about themself, other people, and their relationships overall within that world. Martin Buber, a major 20th century philosopher, highlighted two ways that relational dispositions toward others can be framed: I-Thou and I-It. I-Thou refers to an attitude and orientation toward another that acknowledges his or her individual uniqueness and capacity for holistic responsiveness. I-It, on the other hand, regards persons as to be measured, appraised, judged, and understood merely as members performing a role within a larger group. Thus, I-Thou and I-It represent attitudinal different frames for interpreting and conceptualizing the actions of a person from the actions of an individual.

LEARN MORE: Healing relationships and the existential philosophy of Martin Buber

LEARN MORE: Framing Theory

LEARN MORE: I and Thou

So why is this important? This is important because this sets the stage for how people frame and, thus, make attributions about the various actors and roles those actors play in this constructed stage of life. The outside world has limited awareness, exposure, and insight to the actors and the roles within the youth correctional system. Thus, this lack of knowledge contributes to a relational frame toward youth corrections that more reflects the I-It disposition than the I-Thou disposition. Hence, limited interaction and narrow media exposure can lead individuals to start making generalizations about any group people such as, “They all act like that,” “That’s just the way they are,” or “They are all dangerous.” Now imagine the way with which an individual with a limited I-It dispositional frame will make attributional conclusions about those who interact with the youth correctional system. Now factor in implicit biases. Now factor in race. As you can see, it gets complicated fast. So when someone with a limited knowledge, an I-It frame, and implicit biases begins to make attributions about someone within the youth correctional system, this pseudo-encounter is affected by their interpretation of the other’s behavior. Thus, this outside observer of youth corrections is more predisposed to make conclusions based on dispositional attributions—attributions inferred as a product of the observed person’s personality, attitude, upbringing, i.e. characteristics of who they are—especially when that individual is already labeled “offender.” This label affects both the “offender” and the observer, as the observer automatically has their perception of the individual colored by the title of “offender” and the “offender” has their own self-perception affected as they attempt to process and attribute their own behaviors as being consequential to them as an individual or “an offender.”

LEARN MORE: Attribution Theory

LEARN MORE: Critical Discourse Analysis

Language and labeling are powerful forces that construct the social and cultural world as we know it. The way in which we actually talk about topics is equally as important. The discourse behind these topics is how ideologies are constructed, maintained, and reinforced. So how we talk about youth correctional facilities and their residents matter. Because behind those walls at MacLaren, there are young men with bright smiles and equally bright minds who must constantly face a uphill battle with a system that is stacked against them. Did you know that, when controlled for population, Black and Native American youth face staggering representational disproportionality throughout Oregon’s Juvenile Justice System? Did you know that Oregon has the second-highest rate of sending youth to adult court, which are also primarily minority youths? Did you know that the literal structural development of youth’s brains underlie much of their impulsivity and this isn’t considered when they’re tried as adults? I didn’t. That is until days before visiting MacLaren. However, now I do and, while I can’t change the whole Oregon Juvenile Justice System, I can tell people about my experience at MacLaren and the uphill battle that many of the residents have to face both now and when they get out. Thus, at the very least, I can influence the discourse about this topic and, fortunately, so can you, the reader. So share this post; share this story. They are also always looking for volunteers, guest speakers, and other groups like NW Noggin to visit MacLaren; they can be contacted through the Hope Partnership with the Janus Youth Program. Together you and I can try and change the predominant frame toward youth corrections from one of I-It to one of I-Thou. We just have to share their story first.