Post by Jesse Hamlin, NW Noggin Resource Council member for music and performance.

Jesse is a Portland State University undergraduate in Psychology and completed this work as part of his honors thesis. He also organized Noggin Fest in fall, 2017, which helped bring 21 volunteers to Washington DC to present brains and art at the Society for Neuroscience conference, in the U.S. Congress, and to 750+ K-12 students in area schools!

LEARN MORE: From classrooms to Congress!

In the first year of the Trump administration, our government proposed the dissolution of nineteen publicly funded arts programs, including the National Endowment for the Arts. (Chu, 2017). According to the Nation’s Report Card (NAEP, 2016), art and music scores were already on the decline since 2008 and attendance in art and music programs dropped as well…

LEARN MORE: Statement from NEA Chairman Jane Chu (FY 18)

LEARN MORE: Nourishing cultural roots @ OAEA

The assault on arts education is not new. In 2001, following passage of the Bush Administration’s “No Child Left Behind Act,” there was a ~22% decrease in instructional time for art and music in public schools nationwide (Whitehorne 2006). Although the No Child Left Behind Act did identify art as a “core principle,” the progress measures used (e.g., standardized testing for math and reading), forced schools to direct their curricula towards helping students pass these specific tests.

LEARN MORE: STEAM: Better schools with improv & art

LEARN MORE: No Child Left Behind: A Study of Its Impact on Art Education

Now more than ever, students need affordable extra-curricular programs to stimulate the creativity, achievement, confidence, and neuroplasticity that the arts can deliver…

And while it is intuitive that arts integration in classrooms engages students through novelty and leads them to think about information in new ways (and as Noggin volunteers we see it happen regularly!)…

Cognitive neuroscience research offers evidence, revealing how considering information in multiple ways improves retention through deeper engagement with meaning (semantics), more relevant cues, enactment, oral production, emotional arousal, and pictorial representation (Rinne, et al., 2011). Long-term artistic training can “macroscopically imprint a neural network system of spontaneous activity…” and nurture the growth of more flexible and resilient networks in the brain (Limb, et al., 2014). During the process of creation, inhibitions are lowered, which encourages students to experiment, take risks, and learn without the fear of being wrong (Lopez-Gonzales & Limb, 2012). With this more evidence-based perspective, new doors are opened to educational research and practice, and more robust and substantial methods of teaching and learning can be established.

LEARN MORE: The Effects of Arts Integration on Long‐Term Retention of Academic Content

LEARN MORE: Why Arts Integration Improves Long-Term Retention of Content

LEARN MORE: Musical Creativity and the Brain

Shannon Entropy at Holocene: EPSPs & Entropy!

In addition, heightened brain activity during art and music creation link more parts of the brain, helping to create stronger, more distributed networks, and increasing long term memory of content (Rinne, et al., 2011). There is evidence to show that in only 15 months of instrumental music training, there are significant, visible, physiological changes that happen in developing young brains (Hyde et al., 2009). In fact, many of these changes can still be seen, and appear beneficial, more than 40 years after musical training ends (White-Schwoch, Carr, Anderson, Strait, & Kraus, 2013).

From Noggin at the Doug Fir with Moon Hooch

LEARN MORE: Musical Training Shapes Structural Brain Development

In a very interesting study by Kraus, Slater, Thompson, Hornickel, Strait, Nicol, & White-Schwoch (2014), the authors addressed the problem of high levels of ambient noise and fewer opportunities for complex language interaction in children who come from disadvantaged backgrounds by providing community music lessons. These lessons helped “spark” the neuroplasticity that many of the children from disadvantaged backgrounds would typically miss out on (Kraus et al., 2017). Another study found that children who actively engaged in instrument training had faster and more robust neural processing of speech sound as well as higher scores in literacy. The authors conclude that music-making promotes experience-dependent neuroplasticity and auditory learning (Kraus et al., 2014).

Jesse at Noggin Fest, Fall 2017

These findings were not new. In an older study that looked at the relationship between music training and reading skills such as phonemic discrimination, reading performance, and correct changes of pitch and timbre, it was found that discrimination of musical sounds gained from musical training is related to reading performance, literacy, and linguistic achievement (Lamb & Gregory, 1993).

LEARN MORE: The Relationship between Music and Reading in Beginning Readers

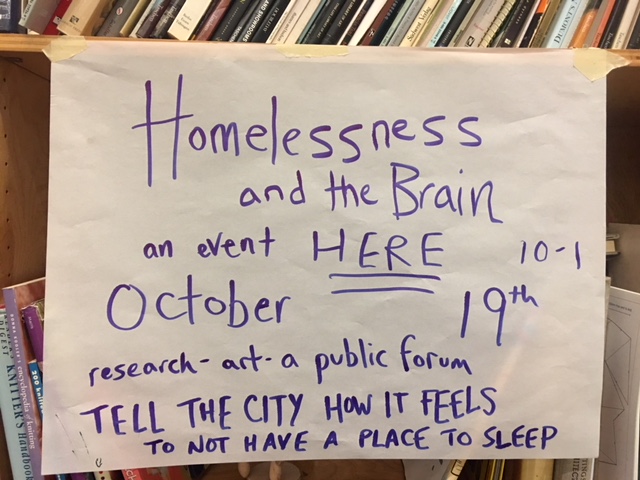

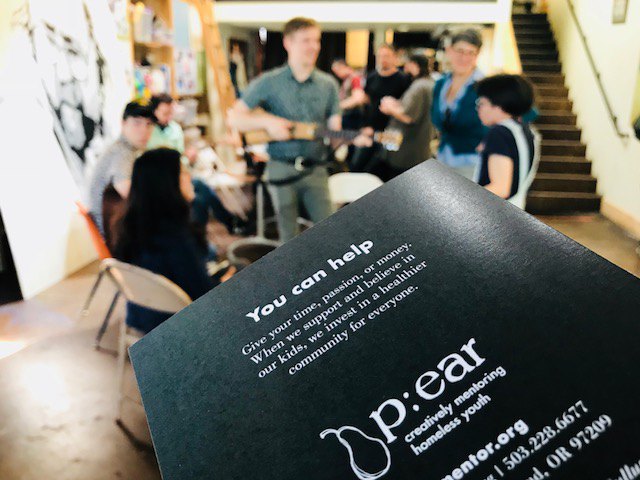

Last fall, NW Noggin collaborated with p:ear, a homeless youth organization in downtown Portland, to bring together graduate and undergraduate brain researchers and outreach volunteers, clinicians, policy makers and, as equal participants, valuable young members of our community who still lack safe, secure places to call home.

LEARN MORE: Landscapes of the Brain: Seeing us all through research & art

LEARN MORE: Noggin at p:ear

Those in our community without safe, secure housing not only struggle with sleep deprivation, high levels of ambient noise, and a lack of opportunity for complex language interactions or art-making, but are often dehumanized.

Neuroimaging shows that recognition of people belonging to “extreme out-groups” (e.g., homeless youth, those with drug use disorders) is processed in the brain differently than those from “in-groups.” The brains of subjects respond to images of those without homes as if they were potentially non-human “objects of disgust” rather than fellow human beings (Harris & Fiske, 2006). This represents a significant problem for those of us with safe beds to sleep in, too, for a failure to appreciate other people as people has consequences for the health of our society.

LEARN MORE: Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups

LEARN MORE: Dehumanized Perception: A Psychological Means to Facilitate Atrocities, Torture, and Genocide?

This level of dehumanization and social isolation, in combination with the variability of brains and brain networks involved in social and rational decision making during adolescence (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008), creates an environment that can be hostile to brain development.

Impairments have been found in visuomotor skills, problems solving skills, judgment, logical thinking, and processing speed. In addition, homeless children generally score lower on tests of verbal abilities, and have significant deficits in attention (Edidin, et al., 2012). Considering the high rates of mental illness, sleep deprivation, and inequities in access to resources (Smedley et al, 2001) within homeless communities, the need for intervention seems obvious.

LEARN MORE: The mental and physical health of homeless youth: a literature review

LEARN MORE: Inequality in Teaching and Schooling: How Opportunity Is Rationed to Students of Color in America

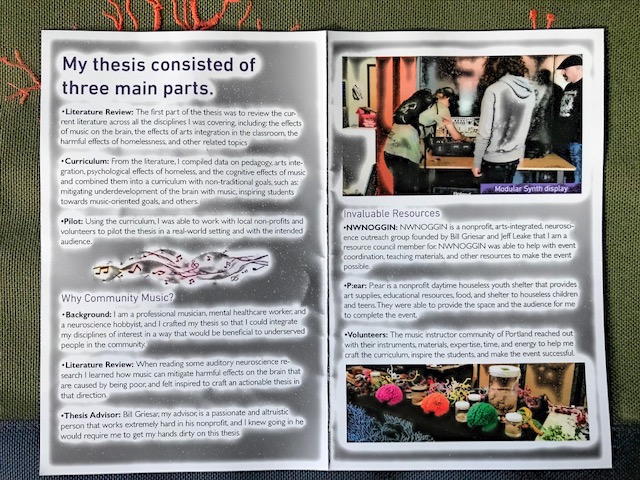

In order to address this need in our own community I crafted a music instruction curriculum designed to impact the problems that homeless youth face because of their situation. I crafted this curriculum to focus on 3 main principles..

- Potential/Mastery – because long term musical training is necessary to fully compensate for the compromised cognitive development of homeless youth, giving students a sense of mastery and musical potential will address the goal of inspiring students to continue to seek out opportunity to learn and make music.

- Performance/Collaboration – in order to address the harmful effects of systematic dehumanization and social invisibility of homeless youth, the curriculum provides students with opportunities to collaborate and perform, helping them to be seen, communicated with, and have a sense of importance.

- Future Orientation – in an effort to address the hopelessness, depression, and suicidal ideation related to homelessness, as well as to encourage students to seek out further musical training, the curriculum aims to provide ways to help students make long-term musical goals, and inspire musical ambitions.

Through NW Noggin, we piloted this curriculum with its targeted audience for three hours at p:ear this spring, teaching community music to houseless youth. We set up various work stations for students to explore basic musical ideas and techniques, including rhythm, and to inspire them to pursue music further. One station was an “Intro to modular synthesis,” which let students make synthetic sounds using a variety of analog hardware modules that changed the electrical music signals in unique ways. There was also an “Intro to signal chain processing,” which involved taking a sound from a guitar or keyboard or other traditional instrument, and running it through a chain of effects that alter it before amplifying it. For example, we used a guitar going through various effects pedals that create sounds like wah, reverb, delay, fuzz, distortion and pitch modulation…

There was lots to do, and explore! Additional stations included Intro to Latin rhythm/melody, Basic guitar techniques, and Basic instrument building from recycled materials.

The first thing that got young people interested in the workshops were all the unique (and occasionally loud!) noises coming from our side of the event space. A bit of novelty and surprise was helpful to spike initial interest…

Once people approached, the volunteer music instructors demonstrated their mastery of the discipline, which inspired confidence in the students towards the instructors, and encouraged some to ask questions about achieving similar levels of mastery.

“This is loud, we’re used to loud. But it’s a good loud…”

Next, the instructors handed off instruments and let kids do as they would, but after a short time started teaching a few basic techniques. This was helpful because the students were able to creatively explore the instrument but were also given some tools to give them a sense of direction, before losing interest. We also had other art stations for painting, some EEG demonstrations of brain activity in response to music, and of course a chance to examine real human brains…

We are indebted to Brendan Deiz, Jake Soffer, Gaile Parker, Eric Sterling, Jade Osilla, Jordan Ray and Oak Alger for joining us. Letting these instructors (many are local Portland musicians) craft their own workshops, and shape their teaching objectives rather than their subject and methods was helpful, especially in a volunteer setting, because the instructors were able to teach confidently, and expertly, whilst still achieving the desired outcome of outreach in musical training.

The students’ response was positive. There were about twenty houseless youth participating, and several inquired about further musical and instrumental training related to their favorite work stations. Administrators and volunteers at p:ear reported that several more asked about purchasing instruments and instrument building kits after having their interest piqued, and p:ear is already in the process of accommodating those requests! In addition, several instructors signed up for p:ear trainings in order to continue volunteering and do more advanced one-on-one lessons with those who maintain interest.

In conclusion, the curriculum was effective for outreach, for connecting houseless youth to musical instruction, inspiring them towards instrumental training, and introducing them to new musical ideas. The hope is that these effects will continue and grow, helping to reduce, at least to some extent, the glaring gap between socioeconomic status and opportunities for achievement.

LEARN MORE ABOUT JESSE’S HONORS WORK AT PSU…