Post and (most!) photography by Shae Zeimantz, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

“I feel like I’ve dreamed half of my life that hasn’t happened yet, so a lot of times I’m going along, and I do stuff, and I know that I’ve done it. I have déjà vus more than I have regular experiences. If half of your day is a déjà vu, then you start to wonder, ‘What is real and what isn’t?’”

— Marilyn Manson

What is déjà vu? Why do we dream?

Déjà vu is French for “already seen,” and it refers to a state in which one feels as though they have experienced something before while doubting that they ever have. It invokes a sense of familiarity without actual recollection of where exactly the feeling derives.

Are these inaccessible memories, supernatural occurrences – or something else entirely?

Such questions have circulated for as long as humanity has experienced such phenomena. However, with modern advancements in research on the brain we have started to learn more about what may be happening when we experience déjà vu, and also why we dream. While there are no definitive answers to our questions about the causes and mechanisms of conscious and unconscious experiences (yet!), there are now possible explanations that can be explored further through neuroscience research.

During an outreach session at Sunnyside Environmental School, a student asked me a very interesting question: What is déjà vu? The question immediately got my attention, as I had often wondered the same thing many times throughout my life.

However, now I had a different perspective to consider – a neuroscientific perspective.

Another student asked why we dream, and what are dreams? These two questions together stuck in my mind, circulating around and around until I wondered if they might be related. So, I decided to dive into some research articles to find out.

Experiencing déjà vu can feel like a memory is missing; as if you should be able to remember something specific, but can’t. You are just left with that sense of familiarity.

This close relationship to memory has led researchers to explore whether déjà vu is related functionally to memory structures in the brain. Thanks to modern brain imaging technology, we have gained further insight into what areas of the brain are active during various cognitive activities, including memory formation, consolidation, and recollection. What about déjà vu?

LEARN MORE: What is déjà vu? What is déjà vu?

LEARN MORE: What Causes Déjà Vu?

Memory

There are many different types of memory, but the most commonly known are short-term memory (a.k.a., working memory) and long-term memory. Long term memory branches into more types of memory, such as explicit (including episodic and semantic) and implicit (including procedural).

When we consider the concept of “memory,” we’re typically thinking about episodic memory and semantic memory. Episodic memory is our memory for specific events, and are unique to each person based on their experiences. They are what might be portrayed as a flashback in a movie. Semantic memory is our ability to recall facts such as word meanings, numbers, and concepts.

LEARN MORE: Cognitive Neuroscience of Human Memory

LEARN MORE: Working memory, long-term memory, and medial temporal lobe function

LEARN MORE: Conscious and Unconscious Memory Systems

Where is memory?

How are memories formed?

When we experience something in the form of stimuli, either external or internal, the signals are sent to our brains where they are perceived, processed, and eventually consolidated into long-term memory.

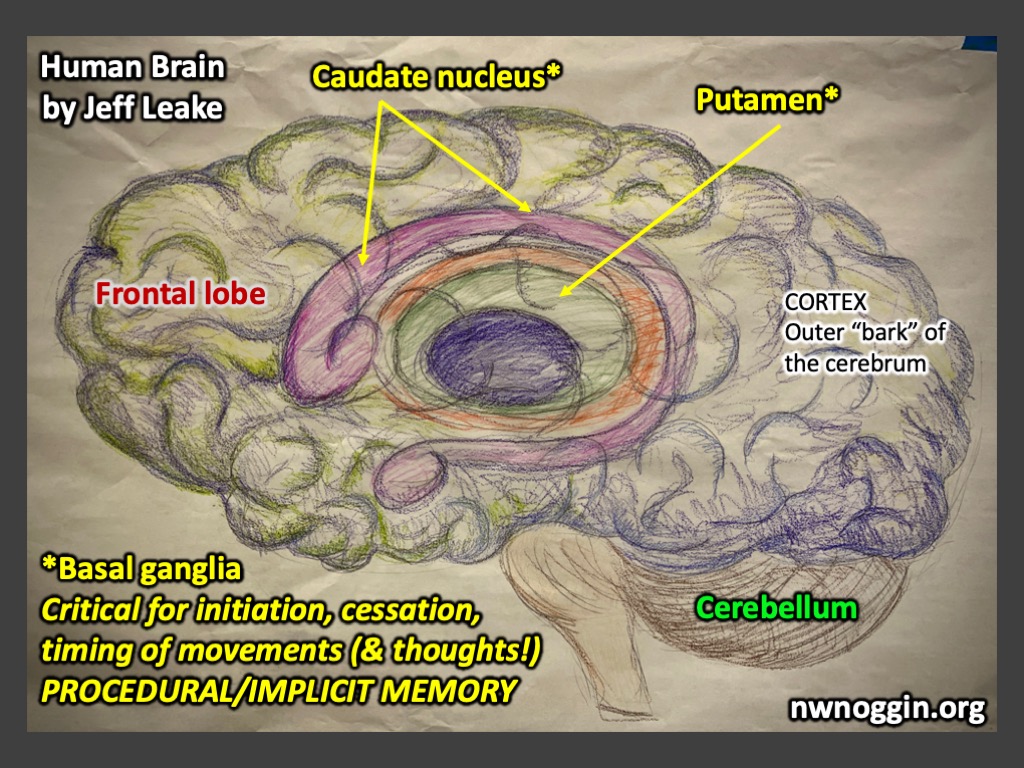

Different types of memories are processed and stored in different parts of the brain, and there is no single, distinct “memory center.” Rather, there are a few key areas that play vital roles in the formation and recollection of various types of memory, including the hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), neocortex in general, basal ganglia, and cerebellum.

The PFC is the main structure responsible for short-term, or working memory. The hippocampus is critical for the formation and initial storage (up to three years) of our episodic memory. The neocortex, or the wrinkled outermost layer of the brain, is the structure housing most of our general knowledge. It is where we form connections for long term memory retrieval after the knowledge is transferred over several years from the hippocampus.

The basal ganglia and cerebellum are involved in forming habits, coordinating and executing skilled movements and learning, but they are largely responsible for movement/motor activity and memory for skills, sometimes referred to as muscle memory.

The amygdala is heavily tied to how we attribute emotional significance to our experiences. In general, memories are stronger when tied to a strong emotion, such as fear, joy, sadness or shame.

LEARN MORE: Where are memories stored in the brain?

LEARN MORE: When I Grow Up: Learning, Memory, and LTP

LEARN MORE: Learning through mistakes!

LEARN MORE: A Dive Into Habits

LEARN MORE: Is memory physical?

LEARN MORE: Brain Structures and Memory

Theories of déjà vu

“Is déjà vu actually the specter of false timelines that never happened but did, casting their shadows upon reality?”

— Blake Crouch, Recursion

There are many hypotheses proposing that déjà vu is linked to memory, and how the experience might relate to and interact with memory networks in the brain.

False activation

One hypothesis is that there is a “false activation” of connections between memory structures and the parts of our brains responsible for perceiving our environment. The hippocampus, as noted, is involved in episodic memory, and the deliberate remembrance of things we have experienced in the past. Nearby parahippocampal structures, are thought to be responsible for distinguishing between what we know as familiar or unfamiliar. The false activation hypothesis posits that déjà vu may come from the activation of these parahippocampal regions without the activation of the hippocampus, leading to the trademark sense of familiarity without any actual recollection of having experienced something specific.

LEARN MORE: Déjà Vu: Possible Parahippocampal Mechanisms

Dual processing

Another similar hypothesis is dual-processing, where two normally coordinated, interactive processes in the brain are disrupted and become asynchronous. This hypothesis offers an explanation for both déjà vu and jamais vu, the opposite of déjà vu, in which one knows that they have experienced something before, but it feels unfamiliar.

According to the dual-processing hypothesis, the two cognitive functions that become asynchronous are familiarity and memory retrieval. When the retrieval of a memory is activated without the familiarity, we may experience jamais vu. We have memories of the experience but it still feels novel and unfamiliar. Alternatively, if familiarity is activated without actual retrieval of a memory, we may experience déjà vu.

LEARN MORE: Entropy, Amnesia, and Abnormal Déjà Experiences

LEARN MORE: A Review of the Déjà Vu Experience

LEARN MORE: Jamais vu all over again

Additional hypotheses

Finally, there are a few more hypotheses all relating to memory.

“We are able to find everything in our memory, which is like a dispensary or chemical laboratory in which chance steers our hand sometimes to a soothing drug and sometimes to a dangerous poison.”

— Marcel Proust

First, there is the theory of unconscious memory storage, which proposes that people do not always pay full or conscious attention to the information that they receive, and thus do not always have a conscious recollection when familiarity resurfaces later and they experience déjà vu. Essentially memory is stored without any awareness of storing it, and thus it feels novel when the memory is retrieved.

Next, there is duplication of processing, which suggests that the content of a memory may not be what elicits the déjà vu experience, but rather the cognitive processes that took place during the experience. If the same or similar mental processes occur in a novel situation, we may feel a sense of familiarity despite knowing that we have not been in the same situation or environment before.

Finally, there is a theory called gestalt familiarity.

Put simply, gestalt is a principle in psychology stating that a whole is perceived as more than the sum of its parts. With regard to déjà vu, gestalt familiarity suggests that when the overall layout of a stimulus or stimuli is similar to what one has experienced in the past, we may experience déjà vu. Even though the individual parts are completely different, if the whole is similar enough to a past experience, we may perceive the scene as familiar despite knowing that we have not perceived it before.

For example, the two images below are clearly different.

However, there are similar elements in a similar enough arrangement that each individual image may feel familiar after viewing the other. Our minds subconsciously connect the two via our memories, and while the connection may seem obvious when the images are next to each other, it may not be so apparent if we viewed the images or approached the gates months or years later. We may not remember why it feels so familiar after significant time has passed.

IMAGE SOURCE: Digging into Déjà Vu: Recent Research on Possible Mechanisms

LEARN MORE: Familiarity from the configuration of objects in 3D space and its relation to déjà vu

Sleep

Many of us, including curious 4th graders, have wondered what exact purpose sleep serves, and we are still looking for definitive answers. We do know the consequences of not sleeping and the side effects of not getting restful sleep, but we do not know exactly what sleep does for our brains and bodies that makes it so vitally important to our ability to function, remember and live healthy lives.

Some theories such as the restorative theory state that sleep gives the body time to repair itself and replenish the components it needs for biological functions during the day. Other theories, such as the brain plasticity theory, focus more on the brain itself rather than the body as a whole, and state that sleep allows the brain to reorganize and grow neural connections. There is extensive evidence that sleep has an important role in memory, specifically memory consolidation.

LEARN MORE: Physiology of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Noggins in Nod: The Science of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Memory and Sleep: How Sleep Cognition Can Change the Waking Mind for the Better

LEARN MORE: Sleep, dreams, and memory consolidation: The role of the stress hormone cortisol

LEARN MORE: Marcel Proust: genius and insomnia

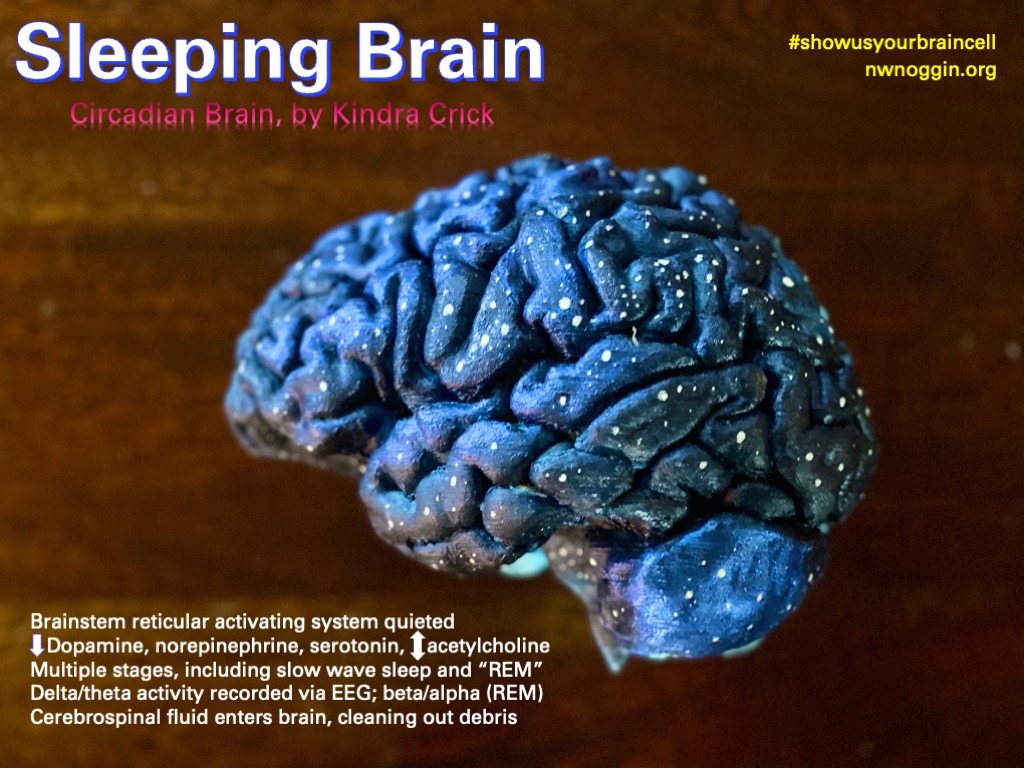

When we (or my cat) sleep, our brain activity cycles through multiple different sleep stages throughout the night. These stages can be divided into two main phases of sleep: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM).

Many people have heard of REM sleep as this is when most dreams occur. When we sleep, our brains are cycling through very different levels of activity and performing different types of tasks than when we are awake. These special conditions allow our brains to better transfer and store recent memories, in a sort of “offline” memory consolidation process.

LEARN MORE: Sleep On It: How Snoozing Strengthens Memories

LEARN MORE: About Sleep’s Role in Memory

Why do we dream?

“Yesterday is but today’s memory, and tomorrow is today’s dream”

— Khalil Gibran

The purpose of dreaming is still largely unknown. However, there are a few ideas.

One idea is the activation-synthesis hypothesis, which suggests that dreams do not have any real meaning, but are driven by random electrical activity that triggers visual and motor hallucinations, and chaotically pulls details from memory. This is potentially why our dreams often feel so bizarre.

LEARN MORE: What is a dream?

LEARN MORE: Dreaming: a neuroimaging view

LEARN MORE: Dreaming Breaks Science…

Various imaging studies have shown that many parts of the brain that are important for memory formation are particularly active during sleep.

Some are more active during NREM sleep, such as the hippocampus and parahippocampal regions. Some are more active during REM sleep, including areas relating to motor memory and motor learning.

In REM sleep, the basal ganglia (motor control and motor memory) and the amygdala (emotional memory) are active. These increases in neural activity are thought to be interpreted by the brain as sensory stimuli, leading to visual and motor hallucinations. These hypotheses and observed activation of these areas of the brain may explain why our dreams are often filled with strong emotions (amygdala activation), why they often feel familiar (memory structure activation), and why they are often chaotic and random (activation-synthesis hypothesis and random electrical impulses during sleep).

LEARN MORE: The Neurobiology of Dreaming

LEARN MORE: The Art and Neuroscience of Narrative

LEARN MORE: Dreaming and the brain: from phenomenology to neurophysiology

LEARN MORE: Investigation on Neurobiological Mechanisms of Dreaming in the New Decade

Are Déjà Vu and Dreams Related?

How are memories, déjà vu, and dreams all connected?

Poring over this research made me realize that these experiences all utilize the same networks in the brain, so perhaps the processes behind them are more connected than we think. Often, déjà vu feels like a dream. Does the sense of familiarity we feel come from a dream that we’ve forgotten?

We have come a long way in our understanding of how the brain works, particularly in relation to memory, but there is still a lot we do not know about the deeper mechanisms of these processes, and how they may be playing hidden roles in our daily lives.

What about déjà-rêvé?

There is also another phenomenon that is not as common as déjà vu or jamais vu, but is equally fascinating. It is called déjà-rêvé, or “already dreamed” in French, and it can be described as re-experiencing prior dreams. Has this ever happened to you?

Those who experience epileptic seizures are more likely to have déjà-experiences, such as déjà vu, jamais vu, and déjà-rêvé. In short, it is thought that epileptic seizures trigger these déjà-experiences when bursts of electrical activity in the brain stimulate parts of the brain involved in memory.

Interestingly, both déjà vu and déjà-rêvé can be induced by using electrical brain stimulation (EBS), but it appears that the brain areas stimulated to provoke each type of response differs, implying that these two phenomena are in fact distinct. Unfortunately, there is very little research on déjà-rêvé as its own phenomenon, so we still do not have much information on this compelling experience.

LEARN MORE: Déjà-rêvé: Prior dreams induced by direct electrical brain stimulation

The complexity and mystery surrounding these déjà-experiences is truly enthralling to learn about and ponder. I find it incredible to think that we can stimulate our brains and relive dreams we might not have remembered otherwise.

Is it possible to unveil other hidden memories using similar methods? When we discover more about the intricate workings and mechanisms of our memories, what will we be able to accomplish in the scientific and medical realm?

Experiences like déjà vu and dreaming can sometimes feel like something out of a sci-fi movie, so I am extremely grateful for the chance to explore these topics further through brain research and classroom questions, something that would not have been possible without NW Noggin and the neuroscience outreach they provide.