From Night Owls and Morning Birds to Motivating Those with ADHD

Post by Sami Wagner, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

When I arrived at Hazelbrook Middle School for community outreach, I was a bit nervous because I was running a few minutes late. I have a bad habit of leaving the house later than I need to, because I struggle with time blindness due to my ADHD.

“…differences in time perception are a central symptom in adults with ADHD. Some of these differences include the feeling of time moving faster, which causes difficulties in prospective time tasks and inaccuracies in time estimation tasks.”

― Simon Weissenberger

LEARN MORE: Synapses and Seconds in Sisters

LEARN MORE: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (NIMH)

LEARN MORE: Clinical Implications of the Perception of Time in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Review

LEARN MORE: Time Perception is a Focal Symptom of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults

Little did I know, many of the students I would talk to and interact with at Hazelwood Middle School had experiences similar to mine, and they had questions!

“What is ADHD, and how do you motivate someone who has it?”

“How about Autism? Why do people with Autism like specific routines?”

“Why do some people wake up early while others stay up late?”

“Why do people tell you not to go on your phone before bed?”

“Why is it so hard to fall asleep sometimes?”

“How do some people wake up so early, but I can’t even fall asleep until late?”

“How do I make myself go to the gym when I don’t want to?”

“How do you get stronger – what does your brain have to do with working out?”

And in response I wondered: What is going on in someone’s brain when they engage in ANY kind of repeated pattern, like a habit? After many hours of insightful conversations with Hazelwood students, I was even more curious to investigate.

Might we actually get to choose which habits we develop, like whether we’re “night owls” or “morning birds,” or are habits just an unchangeable part of who we are?

What chronotype are you?

Are you a morning bird (up and ready early) or a night owl like me? Or neither?

These patterns are called “chronotypes,” and they impact our sleep, affecting when we feel most awake and most tired. Our lives are governed by biological rhythms, including the circadian rhythms associated with the critical 24 hour cycling of each day (from the Latin “circa diem,” meaning “about a day”). Many factors, including light exposure, exercise, diet, gender, age, school start times – and ADHD – can influence these rhythms, and lead us to different patterns of sleep and wake.

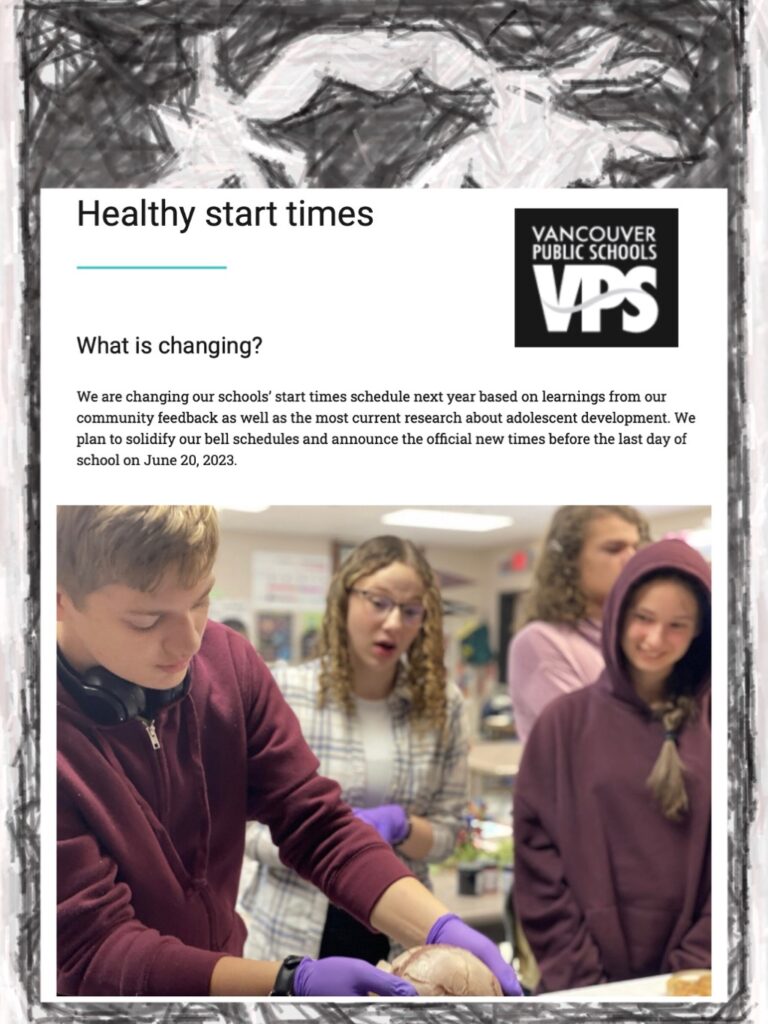

Noggin has discussed neuroscience research on the importance of later school start times for healthy sleep and brain development for years, and party due to this advocacy Vancouver Public Schools will shift from 7:25am to 8:40am for high schools this fall!

“The mismatch between internal timing and social schedules results in desynchronization of an individual’s habits: adolescents and young adults need to fit their chronotype around work/school schedules that impose wake-up times and activation timing contrary to their intrinsic circadian preference.”

― Angela Montaruli et al (2021)

LEARN MORE: Hey Vancouver: Let Kids Sleep!

LEARN MORE: Biological Rhythm and Chronotype: New Perspectives in Health

LEARN MORE: Sleep-Wake Timings in Adolescence: Chronotype Development and Associations with Adjustment

LEARN MORE: Relationship between chronotype and mental behavioural health among adolescents

Patterns and Habits

When a pattern is ingrained in our daily lives, it becomes a habit, for better or worse.

Night owls may stay night owls for long periods of time because going to bed earlier can be difficult, and the same goes for morning birds, who may have a hard time staying up late. In short, while we might be able to change our chronotype if we are determined enough, most of us don’t.

Some habits, like which hand we write with (a.k.a. “handedness”) are even more ingrained in the brain and aren’t as easily changed. To do so involves extensive learning and practice, which typically isn’t very practical. Other habits, like regularly working out or leaving the house at a particular time, are things we may have more control over if we decide to do them. We have the power to create or extinguish habits based on what we want to do, though there is a somewhat strict process for habit formation that we must go through in order to encode a new pattern of behavior as a habit in the brain.

LEARN MORE: Are there differences in brain morphology according to handedness?

LEARN MORE: Left-Handers Are Less Lateralized Than Right-Handers for Both Left and Right Hemispheric Functions

Why do we need habits?

Why are they so hard to establish and break?

There’s a lot more to forming or changing habits than just doing something out of sheer willpower, because your brain works to make it easier for you to move throughout your day using reflexive habits.

This is because making conscious, considered decisions uses a lot more energy, so patterns of behavior in response to specific circumstance wire together certain parts of the brain to more automatically engage our habits – so we can use less.

Creating habits can be a long and challenging process because your brain needs time and energy to associate patterns of behavior with given stimuli. It takes practice. Likewise, breaking habits takes a lot of sustained mental energy and effort because your brain is forced to alter connections between areas linking past circumstances and behavior, which is often very hard to do.

Some researchers suggest that people who have Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) exhibit differences in how easily their synapses can change (i.e., synaptic plasticity), somehow leading to repetitive, habitual behaviors and strong preferences.

LEARN MORE: Autism Spectrum Disorder (NIMH)

LEARN MORE: The Intense World Theory – a unifying theory of the neurobiology of autism

LEARN MORE: Molecular Mechanisms of Aberrant Neuroplasticity in Autism Spectrum Disorders

LEARN MORE: Fundamental Elements in Autism: From Neurogenesis and Neurite Growth to Synaptic Plasticity

So, how do habits (like chronotypes) form?

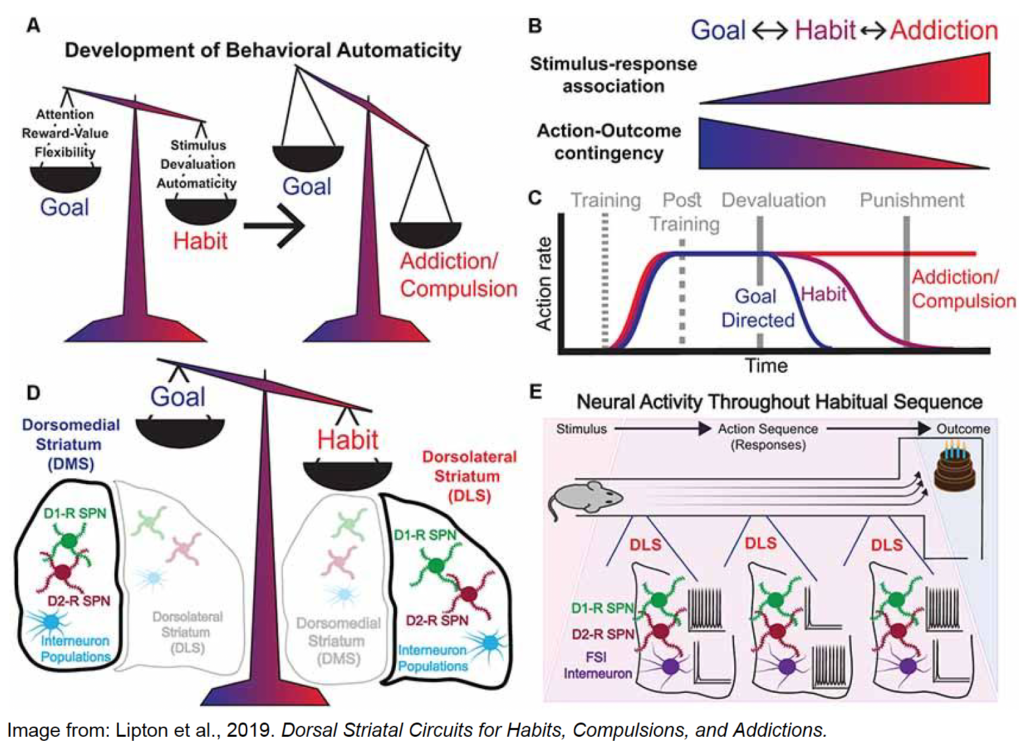

Habits, also referred to as examples of “behavioral automaticity,” are an important way for the brain to decrease the demand for energy-consuming decision-making tasks.

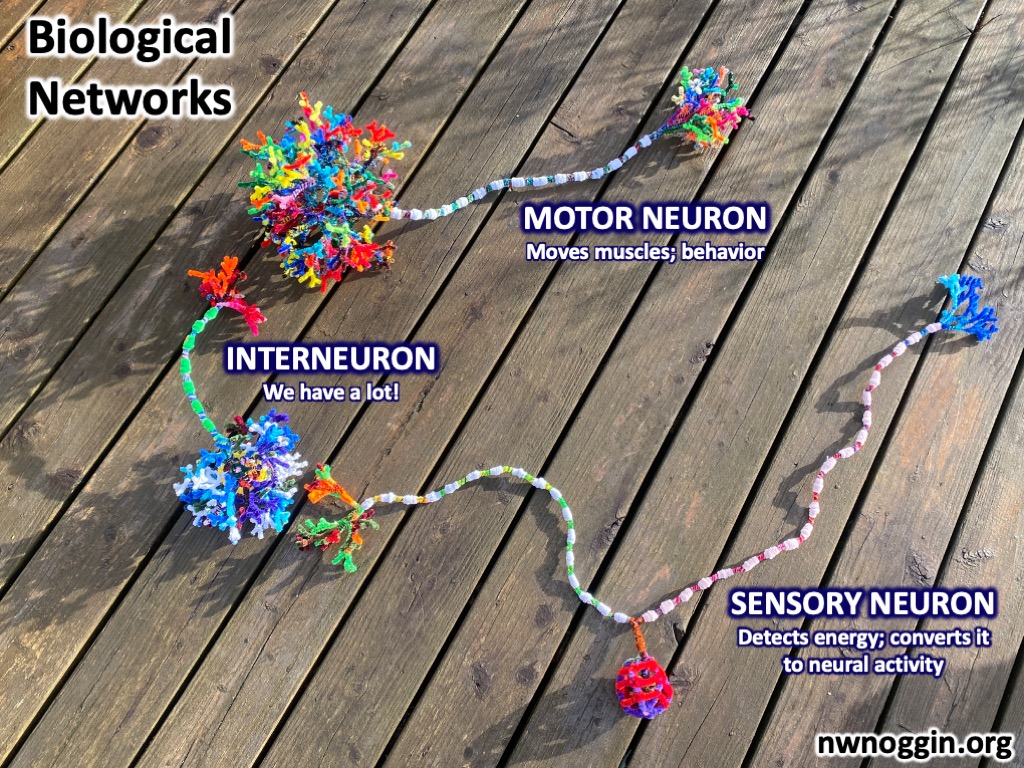

The process for habit formation is pretty familiar; you do something regularly for long enough that it becomes an automatic part of your routine. As a behavior becomes a regular process, especially in a certain context (like brushing your teeth every night before you go to bed, or waking to an alarm clock at a certain time each day), microcircuits form through repetition and the behavior and context essentially get networked in parts of your brain that are really good at pattern-recognition and initiating actions.

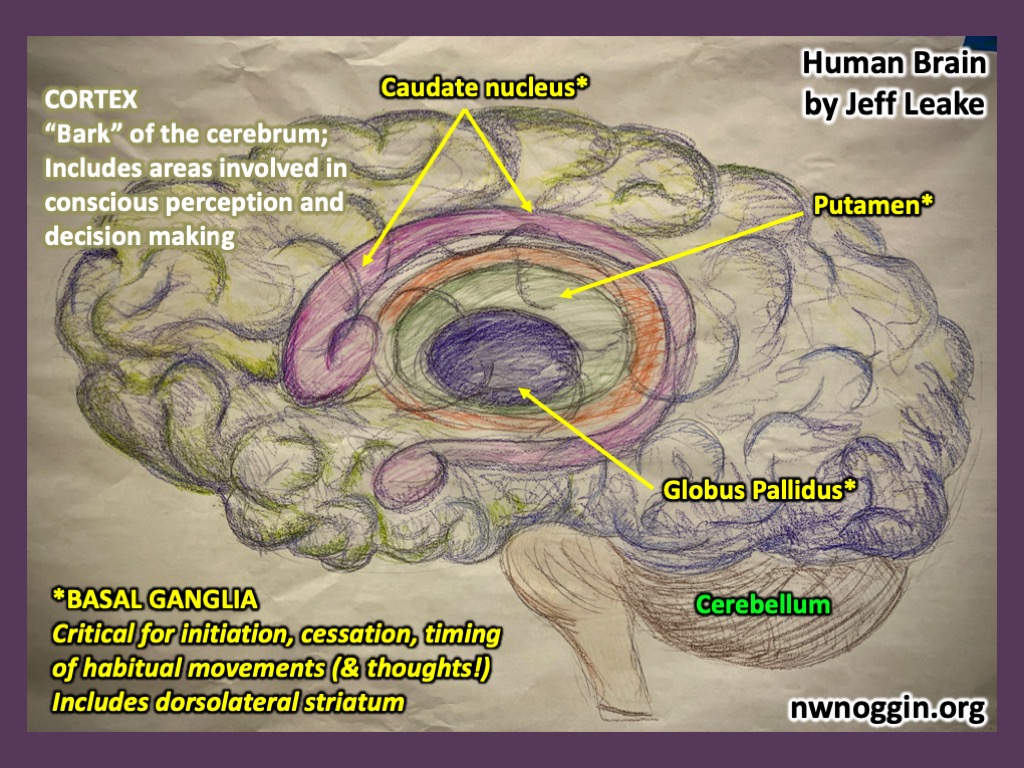

Habitual behavior is linked to the corticostriatal sensorimotor loop, which links two important brain areas: the sensorimotor cortex (cortical areas involved in conscious perception and considered social behavior) and part of the basal ganglia (a set of interconnected subcortical structures) known as the dorsolateral striatum.

The sensorimotor cortex is the mediator that allows us to sense things and move around or, in the case of habitual behaviors, perceive stimuli or situations and initiate action, while the dorsolateral striatum can be thought of as our “habit manager” that helps us perform our habitual behaviors in familiar settings by recognizing the patterns of stimuli associated with a behavior and just doing it.

For everyone, this might mean having a strong preference for a familiar routine, or habit.

LEARN MORE: Dorsal Striatal Circuits for Habits, Compulsions and Addictions

LEARN MORE: Sensory Processing in the Dorsolateral Striatum: The Contribution of

Thalamostriatal Pathways

In addition to neural habit pathways, other factors influence us, including hormones.

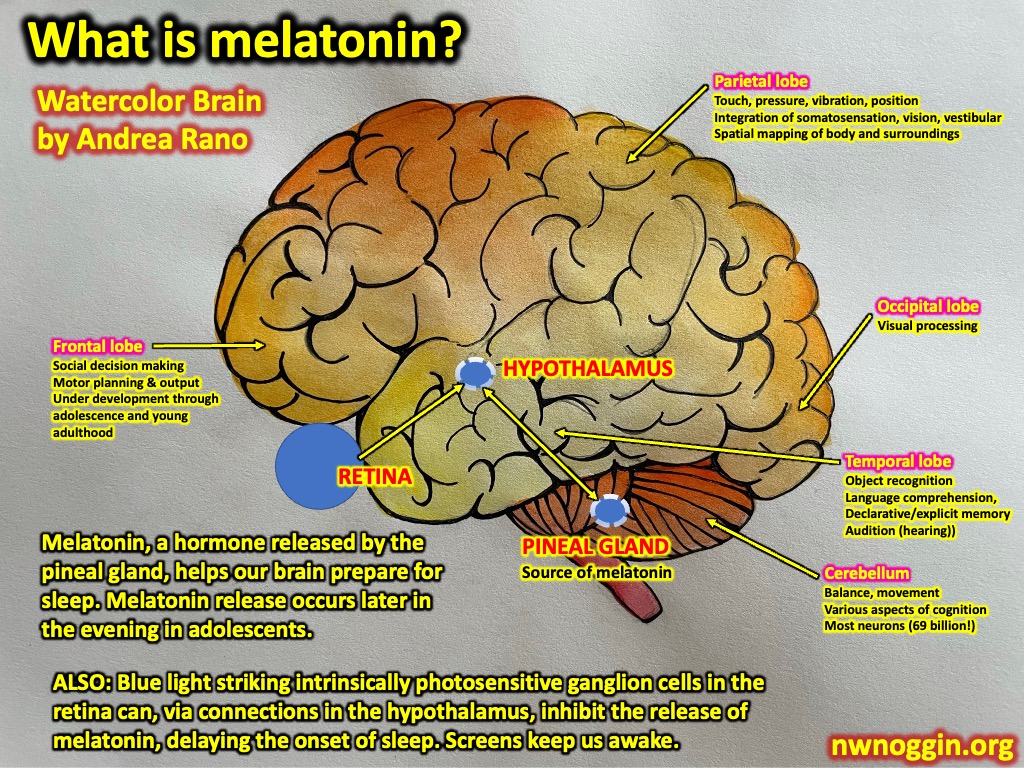

The pineal gland on the back (or the dorsal surface) of our brainstem secretes the hormone melatonin in response to declining levels of light, which signals the brain to prepare for sleep. Exposure to bright/blue light, however, stops that release. So the questions “Why do people say you shouldn’t go on your phone before you go to sleep?”, “Why do I have such a hard time falling asleep?” may be partly answered by considering this powerful impact of light.

Turn off your phone and close the curtains if you want to sleep.

LEARN MORE: The influence of blue light on sleep, performance and wellbeing in young adults

LEARN MORE: Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin

How do you break a habit?

Breaking a habit is hard work, but it is fairly simple (usually).

Stopping habitual behavior means inhibiting the automated response from the dorsolateral striatum, which can be difficult, but is nevertheless doable. This means that in order to break a habit, you just don’t do it. Very simple and very unhelpful advice.

A better approach can be identifying alternative behaviors to engage in or motivators for stopping. This is due to another network in the brain, the corticostriatal associative loop, which is responsible for goal-driven behavior, and can help redirect habitual behavior by presenting a more enticing alternative.

This pathway connects the prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex, the parts of the brain that activate during reward-seeking, with the dorsomedial striatum, which is very close to the pattern-recognizing dorsolateral striatum, in order to facilitate action to obtain or achieve something rewarding (a goal).

LEARN MORE: The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience

In other words, goals can form AND break habits

Goal-directed behaviors require substantial motivation, so having a goal you care about is a great starting point for engaging or not engaging in a behavior.

Goals can take on a multitude of forms, but they can be boiled down into two categories: tangible reinforcement (rewards) and bigger picture motivators (traditional goals or ideals). This is especially helpful information for those with ASD and/or ADHD who may experience more enduring patterns of behavior and have a harder time breaking unhelpful or distressingly rigid habits, and who require different approaches for forming healthy, supportive habits.

Some brilliant questions came up during outreach at Hazelbrook Middle School, which tie in really well with this concept. A student asked about how ADHD works and how to get motivated when you have ADHD.

Personally I think of ADHD as a bunch of goblins in my brain that really need reinforcement and stimulation, which can make attending to boring things really difficult and focusing on exciting things really easy. My little brain goblins (which actually involve an imbalance of certain neurotransmitters) can be bribed with tangibles like fruit snacks, or other preferred rewards, but it can sometimes take awhile to find “bigger picture” motivators. So, if you have ADHD you might motivate yourself to do something you don’t really want to do by providing little rewards for getting things done, while better sleep (including less light at night) and in some cases medications can help address the chemical imbalance.

LEARN MORE: Creatures of Habit: The Neuroscience of Habit and Purposeful Behavior

NOTE ONE: I, Sami, got myself to work out consistently by rewarding myself with a package of fruit snacks every time I completed a workout. To this day, a year later, it has stuck, no fruit snacks needed.

NOTE TWO: I, Sami, am indeed staying up late to write this post as we speak. It is my bedtime, but alas, finals never rest, so neither do I. But huge thanks to the students at Hazelwood! You motivated my noggin, and I accomplished my goal.