Ahhh…elementary school! The questions are the best!

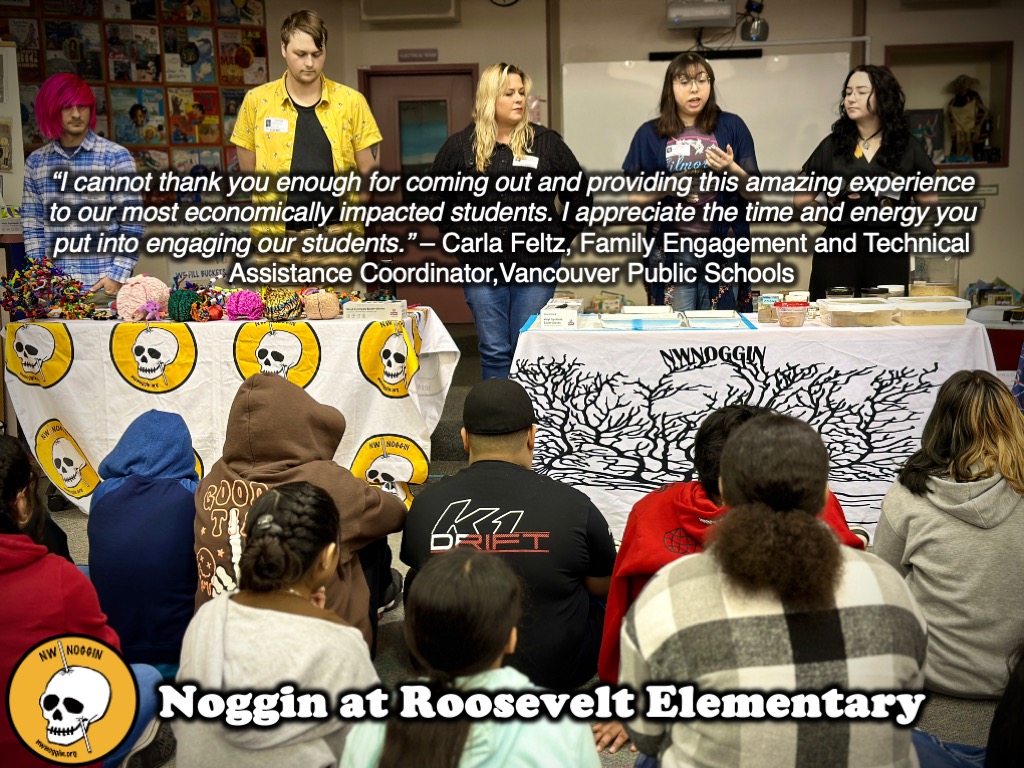

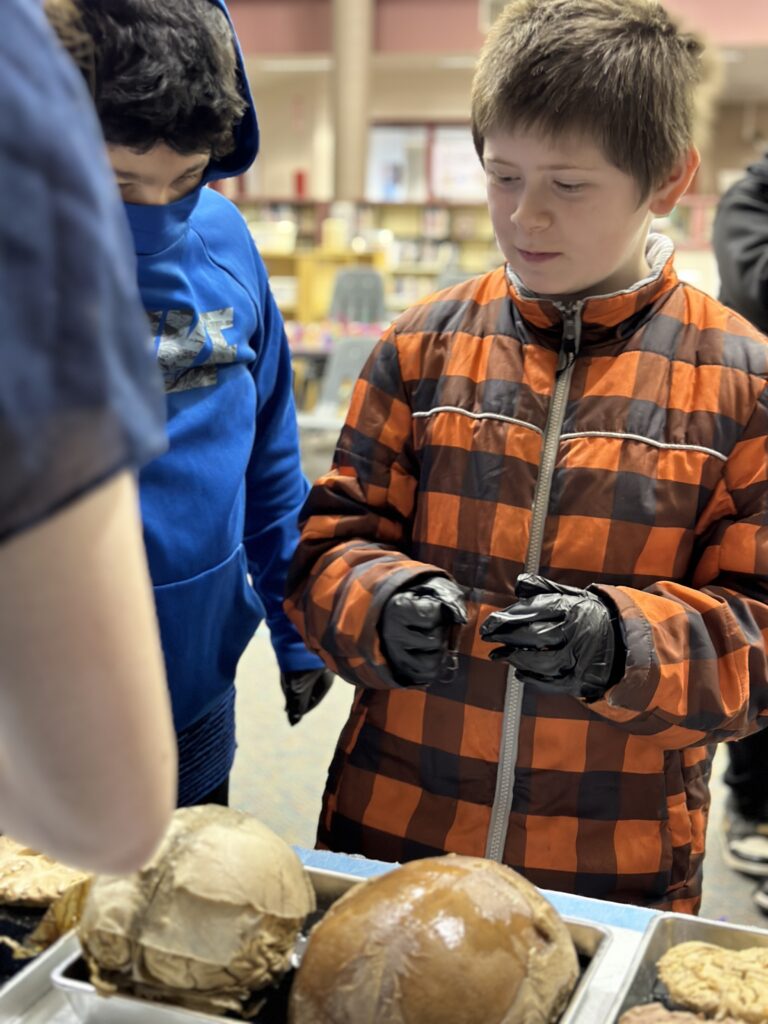

Northwest Noggin volunteers took the Interstate Bridge over the Columbia River north to Vancouver Public Schools, for a morning with energetic students at Eleanor Roosevelt Elementary.

Our community-engaged participants included Bradley Marxmiller and Dr. Denesa Lockwood from OHSU, along with Justin Benner, Brin Rey, Xander Hawkins, Becky Callos and Jennie Terranova from Portland State University.

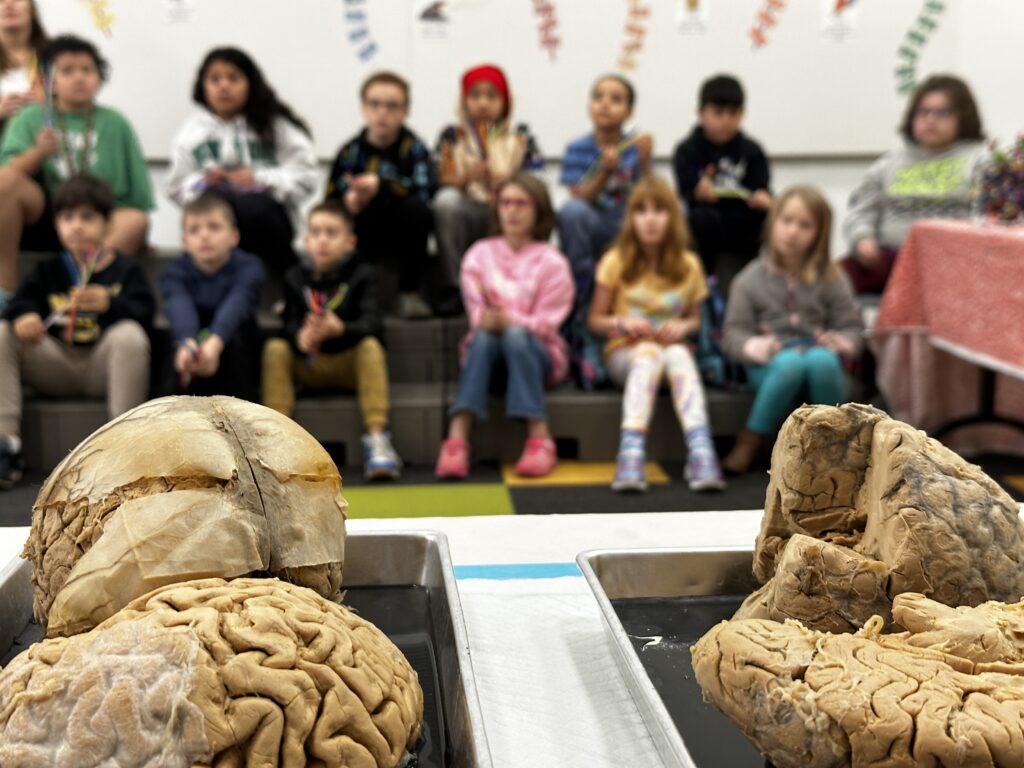

Students had just completed a round of state testing, which teachers described as “demoralizing” and “unpleasant,” and they were thrilled that we’d arrived with extra brains, art projects and volunteers with a genuine interest in the questions and knowledge that students themselves brought to the conversation.

Teachers generously provided our volunteers with coffee and snacks, and we took questions!

“I don’t like testing, and sometimes it makes me throw up. Why do we throw up?”

Throwing up, also known as vomiting or emesis, is usually protective, resulting from exposure to something threatening, including drugs, rotted food, fungi, bacteria, poisons and viruses. If something gets in you that shouldn’t be there, throwing up is a quick way to get it out!

Many other animals vomit, including our fellow primates, and of course dogs and cats. However mice and rats have a different gastrointestinal architecture, and aren’t able to puke! This has made it difficult to study vomiting in rodents.

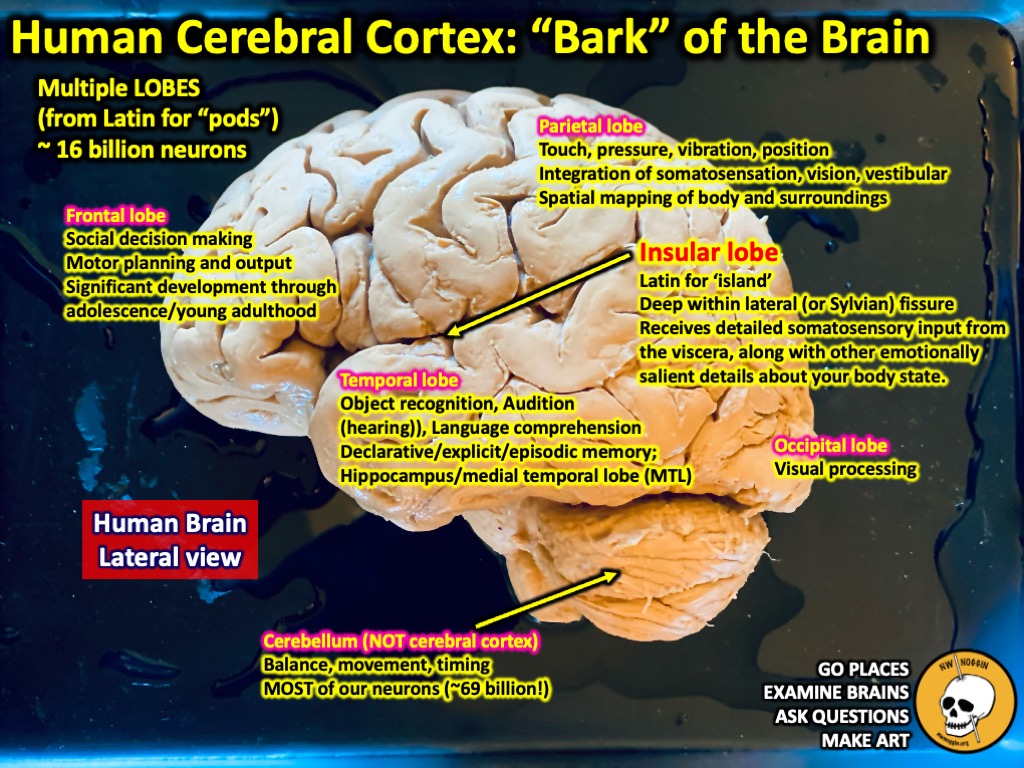

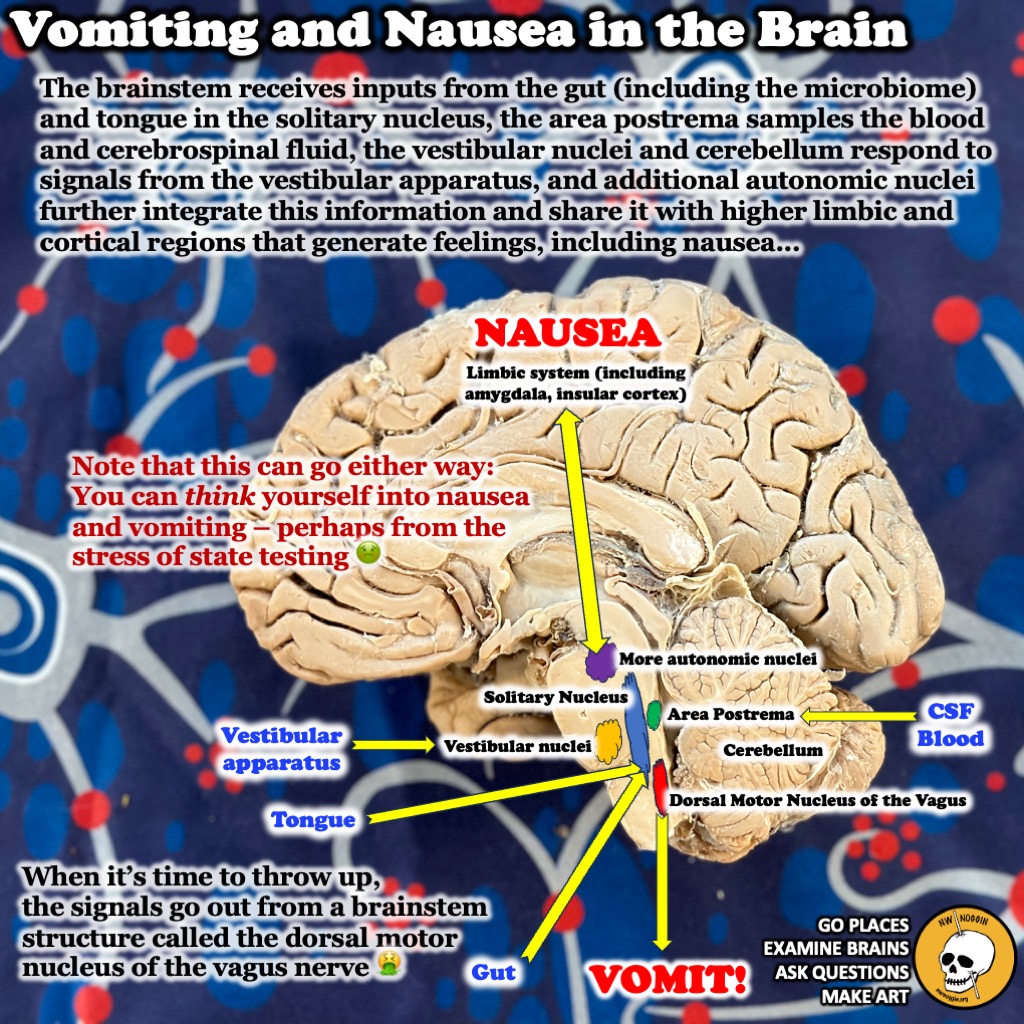

There are many brain and gut areas involved in how we feel viscerally, and how our bodies respond to the foods we consume and the experiences we have, including the fear and stress provoked by state testing. Generally our felt perceptions of our body state – including nausea – involves areas in the cortex, that “bark” of the brain, including an important cortical lobe known as the insula.

“In recent years, tract-tracing studies have supported the view of a central viscero-somatosensory role for the insula, which is now known to receive visceral afferent projections conveying interoceptive information from all over the body. Later studies of direct electro-cortical stimulation confirmed Penfield’s findings. Visceral sensations were described as unpleasant feelings of constriction ranging from a simple breathing discomfort to painful paresthesia, and motor responses included borborygmi and vomiting.”

— LEARN MORE: Structure and function of the human insula

LEARN MORE: Motion sickness increases functional connectivity between visual motion and nausea-associated brain regions

LEARN MORE: Insular Cortex is Critical for the Perception, Modulation, and Chronification of Pain

But there is a lot more going on under that cerebral “hood,” particularly in the brainstem!

LEARN MORE: Why is the neurobiology of nausea and vomiting so important?

LEARN MORE: The role of vagal neurocircuits in the regulation of nausea and vomiting

“Stimulation of the CNS by stress has a direct effect on (the) GI (gastro-intestinal)-specific nervous system…”

— LEARN MORE: The impact of stress on body function: A review

LEARN MORE: Psychosocial stress and abdominal pain in adolescents

LEARN MORE: Symptoms & Causes of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

LEARN MORE: Cyclical Vomiting Syndrome: Psychiatrist’s View Point

LEARN MORE: Treatment of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

There were so many other intriguing and challenging questions that morning, as we met with over 200 elementary school students who held brains, made brain cells, and followed their own interests, enthusiastically challenging us with fantastic insights, queries and observations.

And not one person – despite the noggins – threw up! (For that you may need a state test…)