Post by Cameron McGrew, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor and a Chemistry minor at Portland State University.

The sun shone brightly on a warm spring morning as I opened my eyes, and contemplated the day ahead. I thought about the breakfast I’d fix, the coffee I’d pour, and the class I’d join for outreach, and I got out of bed to start my routine. This series of somewhat scripted but motivating habits began a new day filled with new experiences and wonderful opportunities to learn more about the world.

Yet I do not take these fleeting daily moments for granted, as life has not always been as warm and brilliant as that particular morning in spring.

I am a senior at Portland State University, working towards a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology with minors in both Interdisciplinary Neuroscience and Chemistry. I grew up in a mountain town called Conifer in Colorado, and if you had told me back then that I would come this far, I would have found it unbelievable. Had you told me the same thing four years ago, I would have believed it even less.

I’ve suffered personal family losses directly involving substances, and given the direction my life was going in Colorado, I would have thought myself incapable of achieving what I’ve done so far. I would later learn during my undergraduate studies what might lead to problems with drugs – including the role of an important neurotransmitter called dopamine.

Dopamine

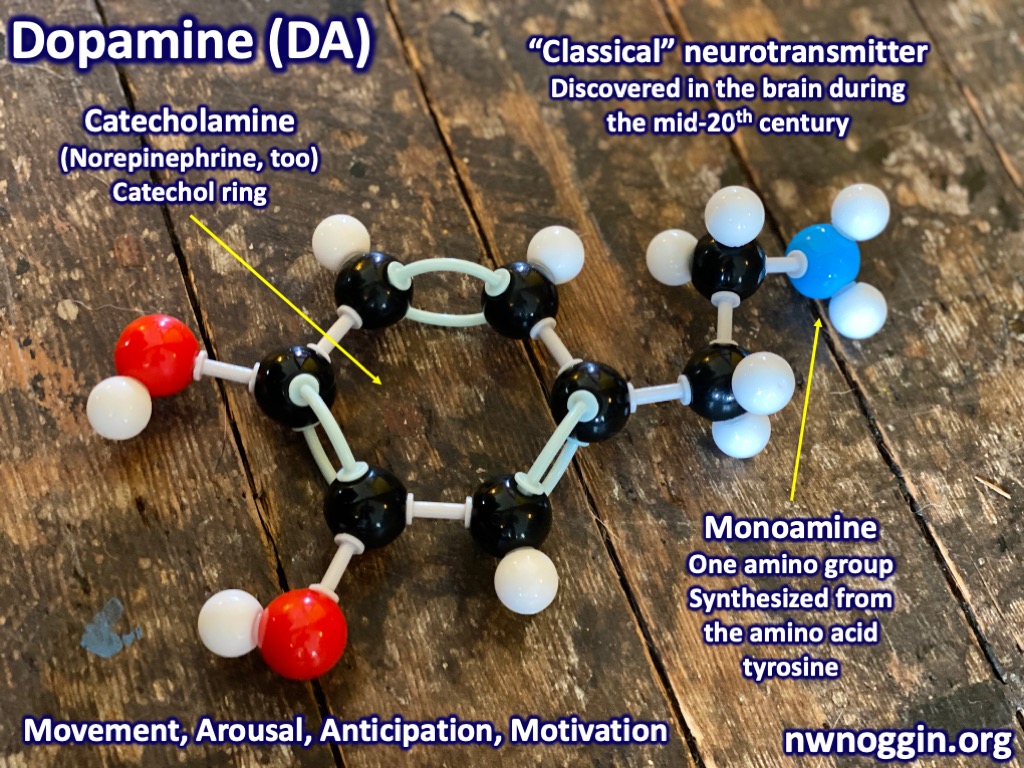

The synaptic release of this small molecule, composed of just eleven hydrogen atoms, eight carbons, two atoms of oxygen and a single nitrogen, is what drives many to fall into the path of a substance use disorder.

LEARN MORE: Substance Use and Co-Occurring Mental Disorders

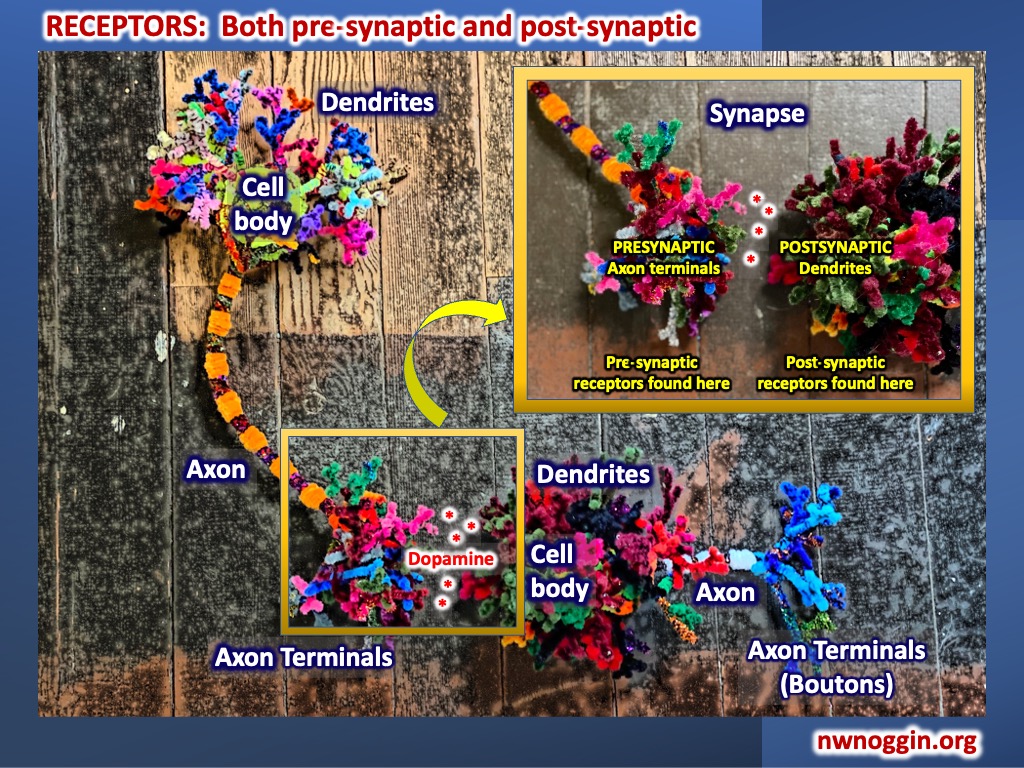

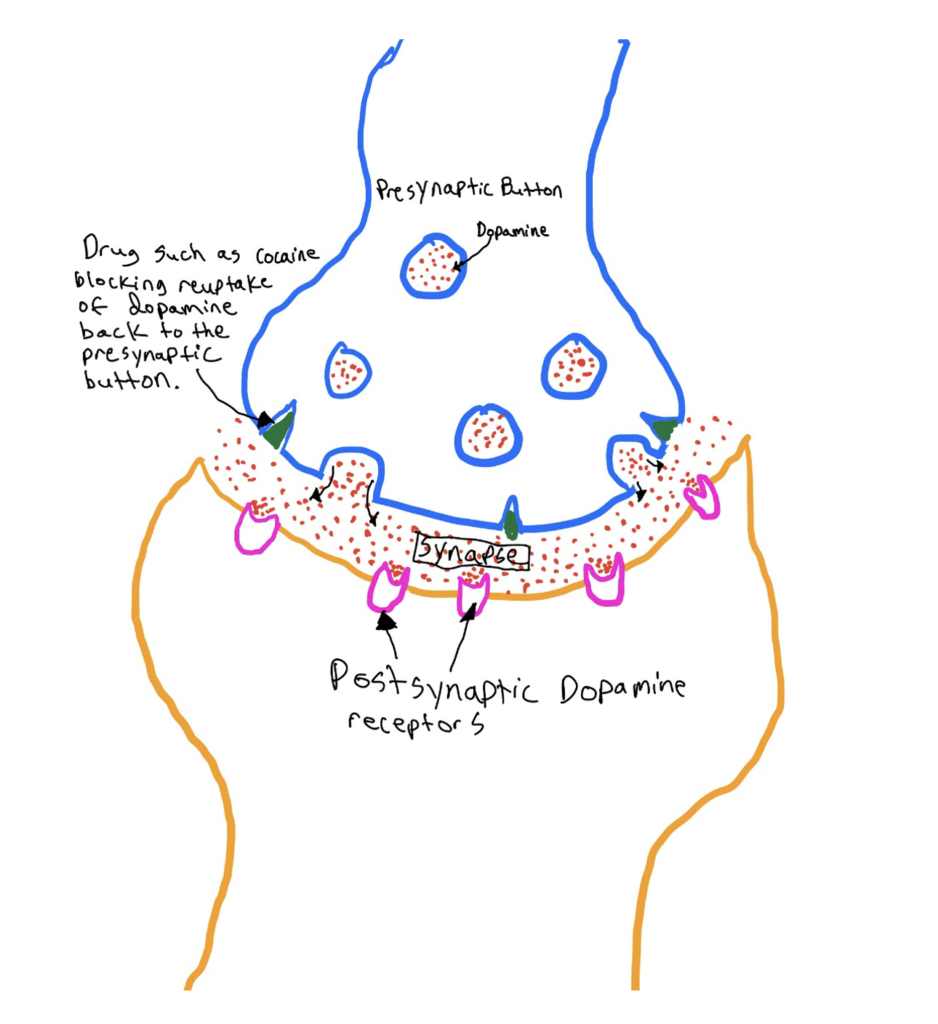

Dopamine is synthesized and stored at the ends of neuron axons, in the axon terminals, or synaptic boutons (French for “buttons”) and released into the synapse where it binds to and impacts protein receptors, many on the next (or “postsynaptic”) neuron to help carry the message along.

Dopamine functions in complex ways but its release is strongly tied to movement, motivation and learning, invigorating and encouraging behaviors in the present and invigorating and encouraging future behaviors too.

Dopamine is removed from the synapse after release, forcibly pulled back into the bouton by protein machines called re-uptake transporters. When removal of dopamine is prevented by a substance like cocaine, which blocks the dopamine re-uptake transporter, it allows more dopamine to accumulate, generating more action at dopamine receptors, and (often) encouraging more motivation and movement. Our brains also learn and remember how to get to this place again.

Dopamine creates anticipation – an excitement and willingness to expend effort – motivating us to re-engage in actions that initially led to its release. Dopamine is released when we do things that bring us unexpected rewards, or that are novel or unpredicted. It helps reinforce these behaviors (including drug use behaviors) to keep us coming back again, and again, and again, and again, and…

LEARN MORE: Dopamine affects how brain decides whether a goal is worth the effort

LEARN MORE: Dopamine does double duty in motivating cognitive effort

LEARN MORE: What Is the Relationship between Dopamine and Effort?

LEARN MORE: Dopamine release drives motivation, independently from dopamine cell firing

LEARN MORE: What does dopamine mean?

But that increased dopamine alters gene expression and changes receptors and synapses. This is where an addiction (now properly termed a substance use disorder) can begin. My personal goal is to help individuals reduce their dependence on the quick and easy drug-induced release of dopamine, because many other wonderful pursuits can release our dopamine too. I want to become a psychiatrist who helps people, and specializes in researching and treating substance use disorder (SUD).

LEARN MORE: Neuroscience of Addiction

LEARN MORE: Drugs, Brains and Behavior: The Science of Addiction

LEARN MORE: Addiction and the brain: the role of neurotransmitters in the cause and treatment of drug dependence

LEARN MORE: Rhesus Monkeys and Biological Addiction

LEARN MORE: How an Addicted Brain Works

Language and Speech

Through outreach I’ve gotten to talk about dopamine, and drugs, and I’ve enjoyed lively conversations with students. And we never know what questions we’ll get at school. That novelty and unpredictability is compelling, and releases a lot of dopamine!

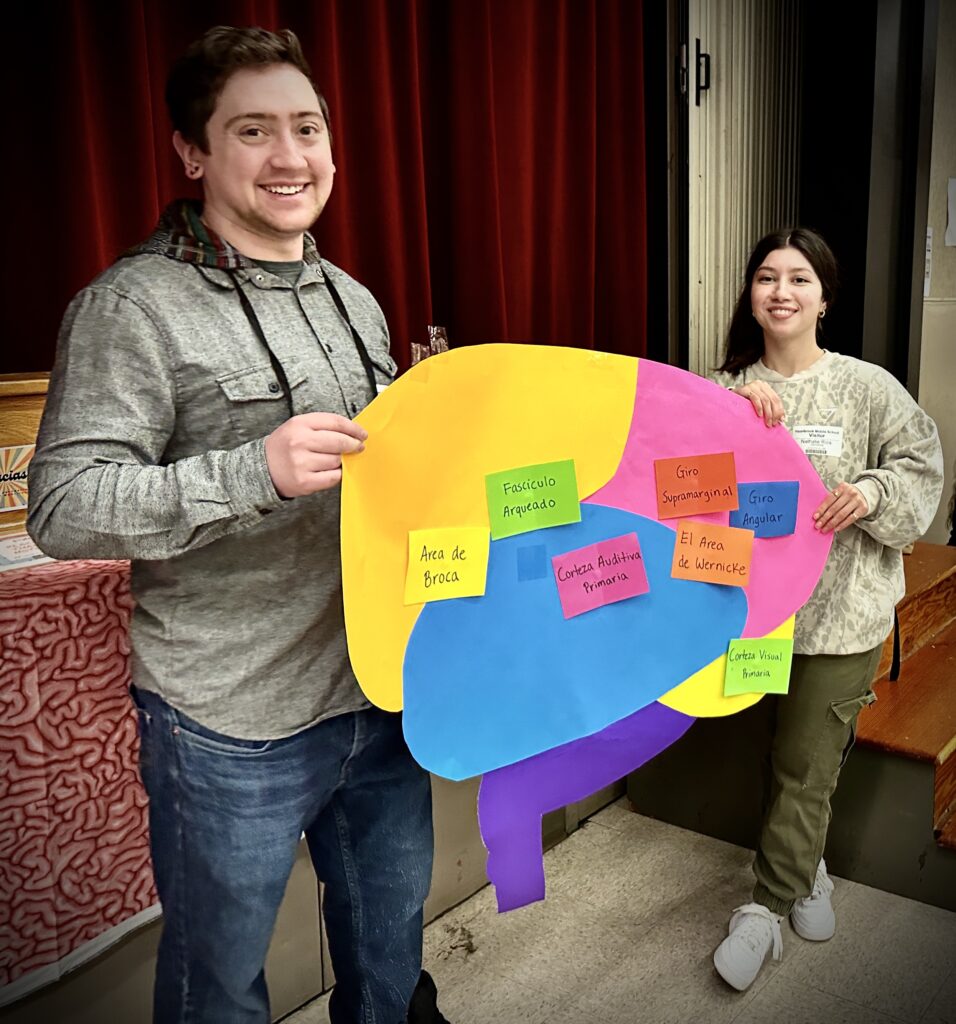

At Hazelbrook Middle School in Tualatin, Oregon, 8th grade students, teachers and staff wanted to discuss language, specifically multilingualism and the impacts of knowing multiple languages on the brain. While preparing for this event, I found a lot of neuroscience research reporting benefits!

Evidence suggests that bilingualism improves executive control and memory in people throughout their lives. There is also evidence to show that a significant benefit to being bilingual or multilingual is that it may offer protection from a decline in cognition, and reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

LEARN MORE: Bilingualism boosts the brain, NIH study finds

LEARN MORE: The effect of bilingualism on brain development from early childhood to young adulthood

LEARN MORE: Evidence for cognitive and brain reserve supporting executive control of memory in lifelong bilinguals

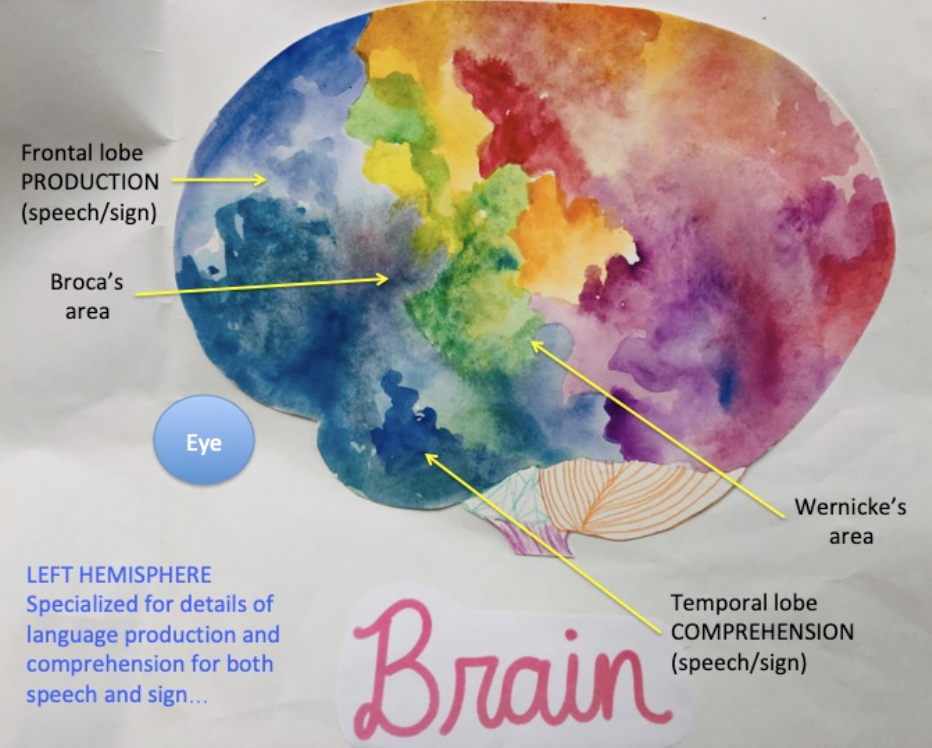

Language is rooted in networks of brain regions, including Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe and Wernicke’s area in the left temporal lobe, with Broca’s more involved in producing language (speech, sign or writing), and Wernicke’s more critical for comprehension. These areas work together, and ultimately contribute to speech output (or sign, or writing) from our primary motor cortex.

While Broca’s and Wernicke’s play a significant role in language, they are each a part of larger networks, more specifically the anterior expression network (frontal lobes) and the posterior comprehension networks (temporal and parietal lobes). These more extensive networks help generate expression and understand speech, sign, writing and Braille.

LEARN MORE: Human brain language areas identified by functional magnetic resonance imaging.

LEARN MORE: Bidirectional connectivity between Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area during interactive verbal communication.

LEARN MORE: The Brain Basis of Language Processing: From Structure to Function.

While at Hazelbrook Middle School, I spoke with students about these brain areas and what might happen if they are damaged or disrupted. Students were even able to create their own neurons in a bilingual presentation during our visit, and I was able to show them a real skull from someone who’d undergone surgery, which garnered so much clear enthusiasm (and dopamine!)!

New questions motivate me

These outreach discussions have been so organic, whether the conversation was with 8th grade students, a 3rd grader, or an adult wanting to know more about how our brains work. NW Noggin has shown me the power of outreach and teaching about the structure and physiology that make up our very consciousness. Seeing the wonder and watching as the gears really begin to turn as students perceive what is being told to them, is a fundamentally unique and worthwhile experience.

And oh my, all the questions!

I have found through going places with NW Noggin that some of the best and most unique questions often come from the most unexpected sources, such as a group of 3rd grade students at Lakeshore Elementary in Vancouver, Washington.

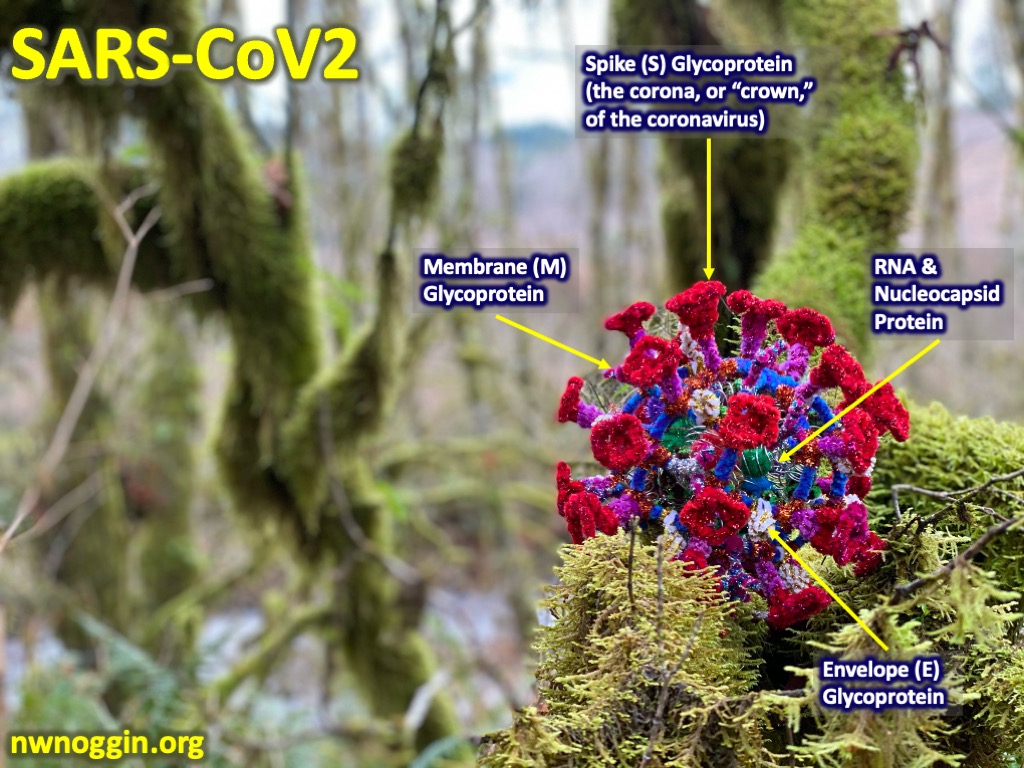

“What’s inside COVID-19?” asked one student, examining a pipe cleaner coronavirus. “What is that jellyfish thing?” asked another, pointing to a hair cell from the cochlea.

During this visit, I was able to expand on many student questions. For example, I was able to draw an ear on the whiteboard and show where the hair cells are located. This discussion came from research I had previously done on hair cells and specialized ribbon synapses that are associated with these cells.

We also discussed the structure of the COVID-19 virus using a coronavirus model crafted for us to use during outreach events. Students wondered what was on the inside of the coronavirus and we were able to explain a bit of how these infective agents work, how they gain access to our cells with their spike proteins, what their RNA does, and how they can reproduce themselves within a body, in a way that these curious 3rd graders could easily understand.

LEARN MORE: Hair cell ribbon synapses

LEARN MORE: SARS-COV-2: Structure, biology, and structure-based therapeutics development

LEARN MORE: Are viruses alive?

LEARN MORE: Defining Life: The Virus Viewpoint

LEARN MORE: Coronavirus and the Nervous System

Speaking with all the students reminded me that each one has a family, people that love them, and statistically it is likely that some of them know someone close with a substance use disorder. This thought drove me even more to pursue a life in psychiatry.

Research has identified several genetic risk factors for addiction, and it is important that we begin to have serious conversations about substance use disorders, where they come from, and identify some of the most at-risk populations to educate about what happens chemically and physically to the brain and body when chronically exposed to certain drugs. If I am even able to help even one person avoid what I experienced, or get their life back, then my life and the work that I do will have been worth it.

LEARN MORE: Children Living with Parents who have a Substance Use Disorder

LEARN MORE: Child Welfare and Alcohol and Drug Use Statistics

LEARN MORE: Addiction science and its genetics

LEARN MORE: The impact of Substance Use Disorders on families and children: From theory to practice.

Is there a videogame use disorder?

I also had the opportunity to visit Paragon Arts Center at Portland Community College (PCC). We convened to support Dr. Bill Griesar’s co-teaching colleague, the artist Jeff Leake and talk with students and gallery visitors about the brain, art and art making and narratives – the stories we tell each other and ourselves that motivate and drive our own thinking and behavior.

LEARN MORE: April is the Cruelest Month by Jeff Leake

During this event, our group had a conversation about video games and the benefits and drawbacks of playing them. There are some definite benefits to the brain in playing video games such as a decrease in reaction time, improved problem solving, enhanced visuomotor performance, and much more depending on the game played and what the mode of action is in that game.

“…children who reported playing video games for three or more hours per day were faster and more accurate on both cognitive tasks than those who never played…children who played video games for three or more hours per day showed higher brain activity in regions of the brain associated with attention and memory…children who played at least three hours of video games per day showed more brain activity in frontal brain regions…associated with more cognitively demanding tasks…”

―NIH Press Release (2022)

LEARN MORE: Video gaming may be associated with better cognitive performance in children

LEARN MORE: Increasing Speed of Processing With Action Video Games

LEARN MORE: Association of Video Gaming With Cognitive Performance Among Children

LEARN MORE: Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review

LEARN MORE: Video Game Playing: Its Effects on Divided Attention, Encoding and Retrieval Processes of Human Memory

LEARN MORE: Video games don’t cause violence

While video gaming has documented benefits, it also has the potential to dominate our time and attention, with the brain releasing dopamine to motivate long days of engagement at the expense of other beneficial pursuits. It is also possible that playing video games too often may lead to a state of “hyperarousal” or a “revving up” of the brain, so it is important to regulate screen time.

This hyperarousal may impact behavior in complex ways, but in some studies it’s been linked to trouble managing emotions, difficulty with impulse control, paying attention, tolerating frustration and more.

Like most things, I feel that we should always strive for balance in benefits and costs.

LEARN MORE: Are video games, screens another addiction?

LEARN MORE: Structural brain changes in young males addicted to video-gaming

LEARN MORE: Impact of Action Video Gaming Behavior on Attention, Anxiety, and Sleep Among University Students

LEARN MORE: Neural Basis of Video Gaming: A Systematic Review

Dopamine is more than drugs

The art gallery event and our days in K-12 classrooms gave me so many opportunities to consider topics I feel strongly about, including video games, neuroscience, and of course addiction and drugs.

And my motivation for these encounters was high!

I realized that dopamine is not just released when we encounter stimuli linked to past drug use, but when we genuinely see each other, listen to and help each other, and when we make art and experience novelty, awe and wonder in galleries and classrooms while holding brains.

And of course, I’ve been lucky to “synapse” with some amazing people along the way!

While I have a long way to go, I will never forget my outreach visits, and the stories I’m now motivated to share. This time in my life is a big stepping stone on a longer road, and I am taking one small step at a time. When reflecting on my days with NW Noggin I find I’m thrilled to have been part of this experience, and I’m more excited for my future helping others to overcome addiction and achieve their full potential in memory of my dad.