Post by Hosanna Broderick, undergraduate in Speech & Hearing Sciences pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

I was born in San Francisco and though I grew up north of the bay, I spent a lot of time in the city during my adolescent and young adult years. I experience profound nostalgia at the sight of thick maritime fog rolling over coastal hills into warmer inland valleys.

Perched on the cusp of two enormous bodies of air shifting under opposing pressures, my breath catches and I pause to contemplate the gulf between myself from long ago and myself in the present moment. I am truly not the same person though I am surrounded by the same fog. I am now someone with something lost but something gained. I feel sadness over the passing of time that has weathered my sense of youthful awe but satisfaction in knowing that the void has been filled with wisdom. The emotional push and pull of my past and present identities mirrors the graceful clash of thermodynamics and fluid movement in the air before me. I know the fog will soon surround me, bringing a darkening chill to a warm summer day, but I can’t help being excited by the return of that familiar sensation.

The coastal topography and sea currents coalesce each summer to form the ground-level cloud phenomenon that haunts the San Francisco bay and my memories of working and playing in the city. These tsunamis of atmospheric moodiness are a much rarer occurrence in my current life living on the edge of the Oregon Coast Range and Willamette Valley, but occasionally a maritime fog will roil over the ridges near my home, thrusting cold, gray tendrils of precipitation down the hillsides.

The sight of an encroaching fog bank can still transport me back to a time of romance, adventure and youthful urban mischief, even when my reality is a middle-aged me walking a geriatric dog down a rural Oregon dirt road.

SEE MORE: Elegant Figures – Time Lapse of San Francisco Fog

SEE MORE: Symphony of Fog – San Francisco Photography and Timelapses

LEARN MORE: What Causes San Francisco Fog? | Exploratorium Video

LEARN MORE: Another Foggy Day in San Francisco

LEARN MORE: Is San Francisco losing its fog? Scientists fear the worst

Northwest Noggin Outreach Program

This Winter, I briefly returned to middle school.

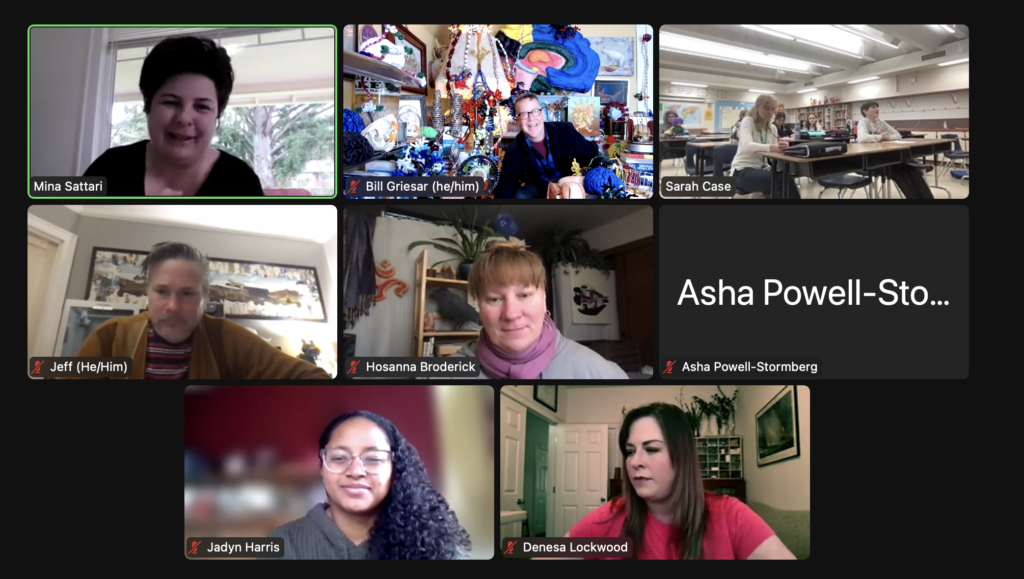

On a chilly February morning, I joined an 8th grade Journalism class at Kennedy Middle School in Eugene, Oregon for a Zoom discussion about nostalgia (and a random fire drill). I came along with other Northwest Noggin volunteers to be interviewed as part of a panel of ‘experts’ on neuroscience by one of their young student journalists, who had chosen the topic himself.

Each of us NWNoggineers brought a different combination of academic study, professional practice, artistic exploration and personal perspective on neuroscience. Our diverse team came ready to tackle questions about how and why nostalgia affects us.

“For every expert, there is an equal and opposite expert”

— Sir Arthur C Clarke

This quote by Sir Arthur C. Clarke transforms a famous Newtonian Law of Physics into a commentary on human nature, capturing the complex, sometimes paradoxical relationship between science and society.

Clarke was a popular science fiction author, but also an outspoken science advocate. He wrote about science and technology advancements throughout his life and promoted research and exploration (most famously into space). Like Clarke before us, we who study science must commit ourselves to sharing our knowledge and working to create a future world where progress and innovations benefit everyone, not just the privileged and powerful. Representations of scientific progress can take many forms, from education and entertainment to sensationalism and propaganda, with the form following its creator’s perspective and intent.

LEARN MORE: Arthur C Clarke: science’s critical cheerleader

LEARN MORE: Science fiction: Shaping the future | Knowledge Enterprise

LEARN MORE: Center for Science and the Imagination

Journalists have a special job in our society to balance information and opinions in their reporting, which often requires cultivating diverse sources. They also have the potential to inspire and ignite scientific curiosity.

I am an artist, activist and mother with a passion for cognitive psychology, neurophysiology, language and learning. I am committed to promoting science appreciation and I was excited to be a part of this journalistic process.

Why does nostalgia affect people?

Nostalgia affects people because it evokes emotional responses.

Emotions are bodily responses to stimuli, in a sense beacons that shine light on relevant information critical to our immediate needs and/or our long-term survival. Similar to a floating icon in a video game, emotions can lead us toward safety and away from danger, toward treasures and away from thieves.

Emotional states drive physical and mental changes that alter our attention, perception, interpretation, and memory of events. These changes allow us to code our experiences for rapid retrieval and future reference. For example, if eating a certain fruit once made us violently sick, we are more likely to live a longer life if we can immediately recall the poisonous memory at the very next sight, smell, taste or even mention of that particular type of fruit, no matter how many years have passed.

LEARN MORE: Why the Tomato Was Feared in Europe for More Than 200 Years | Arts & Culture| Smithsonian Magazine

Emotions steer our behavior like a neurophysiological game of Hot-and-Cold. “You’re warm. You’re getting warmer, warmer, hot, hot. YOU’RE BURNING!”

“Emotional valence describes the extent to which an emotion is positive or negative, whereas arousal refers to its intensity, i.e., the strength of the associated emotional state…”

— Francesca M.M. Citron et al

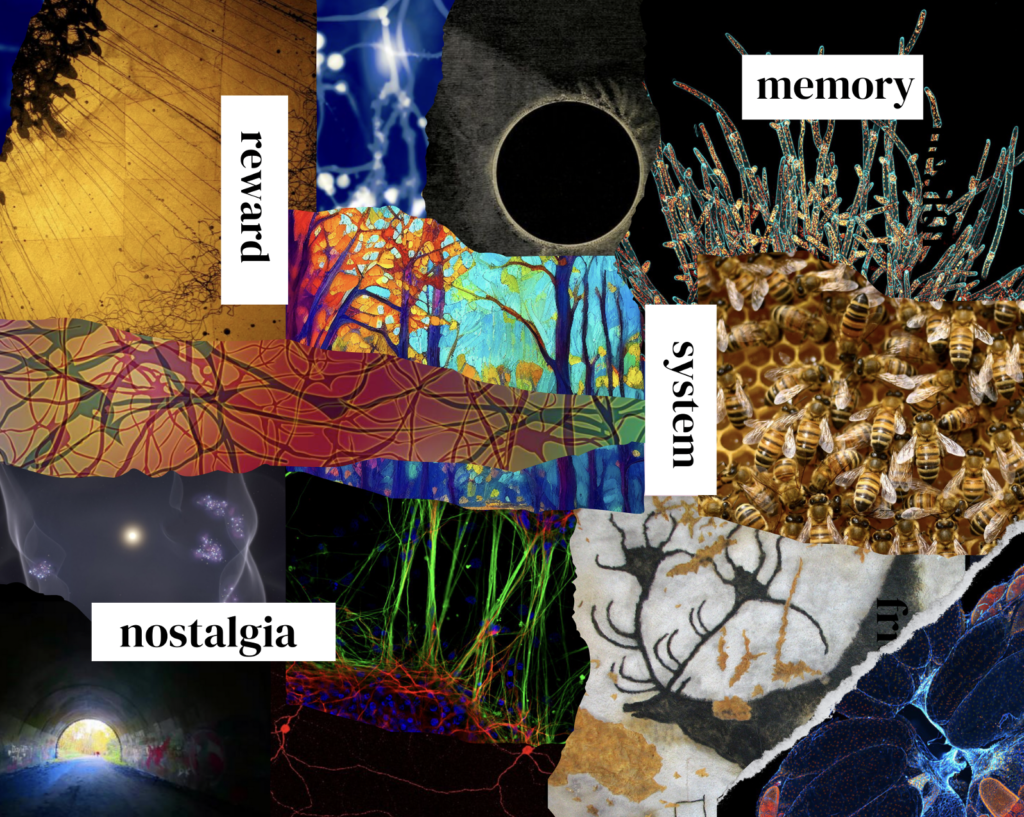

Emotions play a key role in establishing the memories of events and circumstances that evoke feelings of nostalgia. The intensity and valence (spectrum of negative to positive) of emotional coding at the time of the original experience has direct impact on the strength of every pathway leading back to that memory and the amount of neural associations that increase the likelihood of it being re-accessed efficiently.

The significance of low intensity emotions on memory retrieval should not be underestimated. Our minds are exquisitely tuned to the well-being of our bodies, so things like full bellies, nights of good sleep or afternoons of peaceful puttering leave permanent signposts guiding us back to experiences of goodness and comfort.

Along with emotional information, sensory data from past experiences also gets cataloged in our memories with (sometimes) shocking accuracy and detail. Nostalgia can arise suddenly when sensory data like smells, sounds, images, textures, etc. are triggered, effectively autoloading and hitting the play button on past experiences. One of the most surprising aspects of nostalgia is how mundane it can seem. The smell of a certain dish soap can jumpstart the memory of warm evenings in the kitchen of your childhood home. The simplicity does not make it boring. In fact, with nostalgia, the recalled memory is often startlingly more emotional in the present, even if it was unremarkable in the past. This is because nostalgia also triggers the release of dopamine, a reward-system neurotransmitter that motivates action, amps up desire, improves mood and focus and generally feels really good (like from eating, kissing, winning money, etc).

“The past is a candle at great distance: too close to let you quit, too far to comfort you.”

— Amy Bloom

LEARN MORE: The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory

LEARN MORE: Preface – Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward

LEARN MORE: Locating nostalgia among the emotions: A bridge from loss to love

Does everyone feel nostalgia?

The nostalgic response is a normal part of a larger social-emotional process that helps individuals develop a sense of belonging.

Concepts like ‘home,’ ‘family’ and ‘community’ are fundamental to the scaffolded relationship between a person’s self identity and their group identity. Nostalgia gives added weight to memories from childhood, adolescence and early adulthood because they are intense periods of individual and collective development. For people who are in close contact with the people and places of their youth, nostalgia can be milder because of the relative proximity to the source of their memories. People who don’t have a strong bond to any particular people or places from their past would likely experience nostalgia in a more abstract and positive way. People whose connections to their past are profoundly meaningful but made irretrievably distant by factors of time or space are at risk of experiencing nostalgia the most negatively and intensely. Children feel nostalgia too for objects, environments and relationships that have social-emotional importance to them.

Nostalgia is almost always described as having mixed aspects of emotions from both ends of the spectrum. Love and regret. Fear and loyalty. Safety and loneliness. The effect of nostalgia on mood or mindset is also mixed. It can cause people to feel better in the present but it can also cause people to feel worse. It can provoke feelings of social connectedness or feelings of isolation. Both hope and despair can be left in the wake of a wave of nostalgia.

Is nostalgia an illness?

The scientific opinion about the fundamental nature of nostalgia has gone through major transformations in the past half century. Today, most people consider it a positive emotion but in the mid 1600s the term nostalgia was created to describe a pathological sickness that could be fatal.

People reportedly suffered from painful longings so severe that they no longer had a will to live and were even in danger of death from wasting away or by succumbing to wounds, illnesses and trauma.

LEARN MORE: Death by Nostalgia, 1688

Nostalgia affected soldiers, migrants, enslaved and other displaced people, with potentially fatal consequences if left untreated. Indeed, for roughly two hundred years, people died of nostalgia, on battlefields and plantations, in industrial cities and on colonial frontiers.

People living and dying far from their native homelands and cultures struggled to make peace with their memories and nostalgic triggers were often devastating. The social phenomena of collectively feeling nostalgic for an idealized time or place was another aspect of this historical danger. The viral spread of nostalgia could be a public health crisis under the ‘right’ conditions of mass despondency.

LEARN MORE: Nostalgia, and what it used to be

LEARN MORE: The Nostalgia Bone

“There is no pain as great as the memory of joy in present grief.”

— Aeschylus

Aeschylus is known as the Father of Tragedy. The Greek playwright lived 2,000 years before physician Johannes Hofer ‘created’ the disease of Nostalgia, but he would easily recognize the agony of isolation and loss and he would have understood the meaning of the term nostalgia, too.

In the medical tradition of the period, Hofer had combined the Greek root ‘nostos’ which means homecoming or return with the Greek root ‘algos’ which means pain or sorrow.

LEARN MORE: Aeschylus – World History Encyclopedia

LEARN MORE: The Idea of Nostalgia

LEARN MORE: Locating nostalgia among the emotions: A bridge from loss to love

LEARN MORE: The Negative Interactive Effects of Nostalgia and Loneliness on Affect in Daily Life

What goes on in our brains when we feel nostalgia?

Nostalgia accesses memories from our long-term memory storage, combines current emotional state and sensory information with the past emotional state and sensory information and adds a kick of dopamine to boost desire and initiate seeking behaviors.

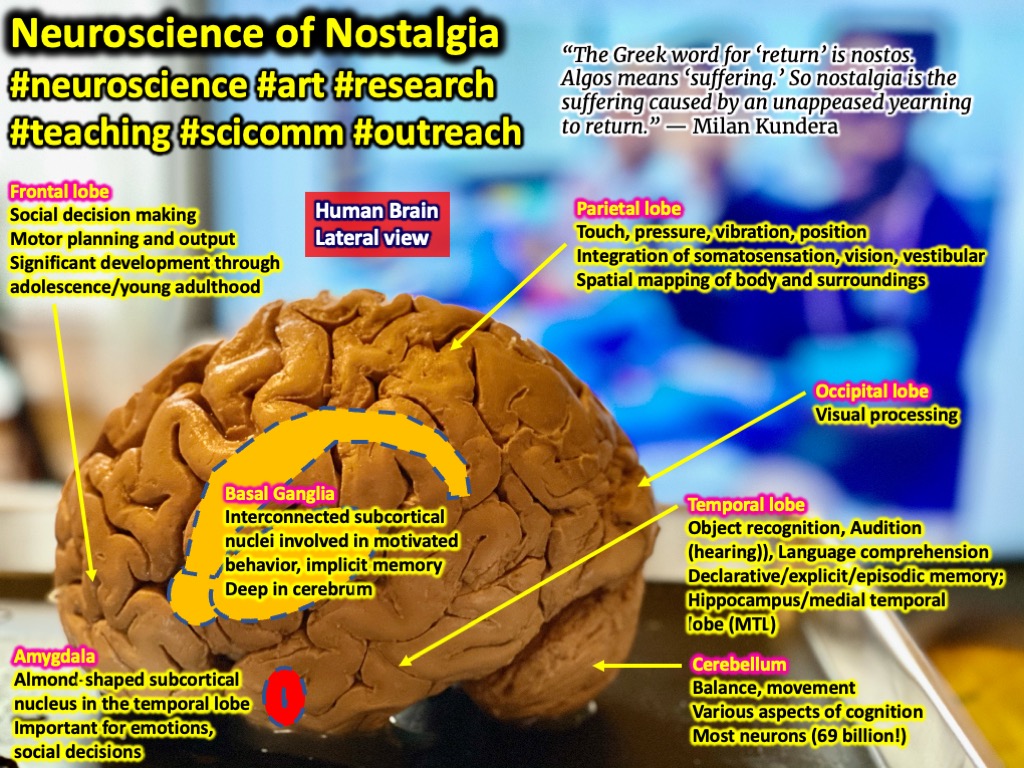

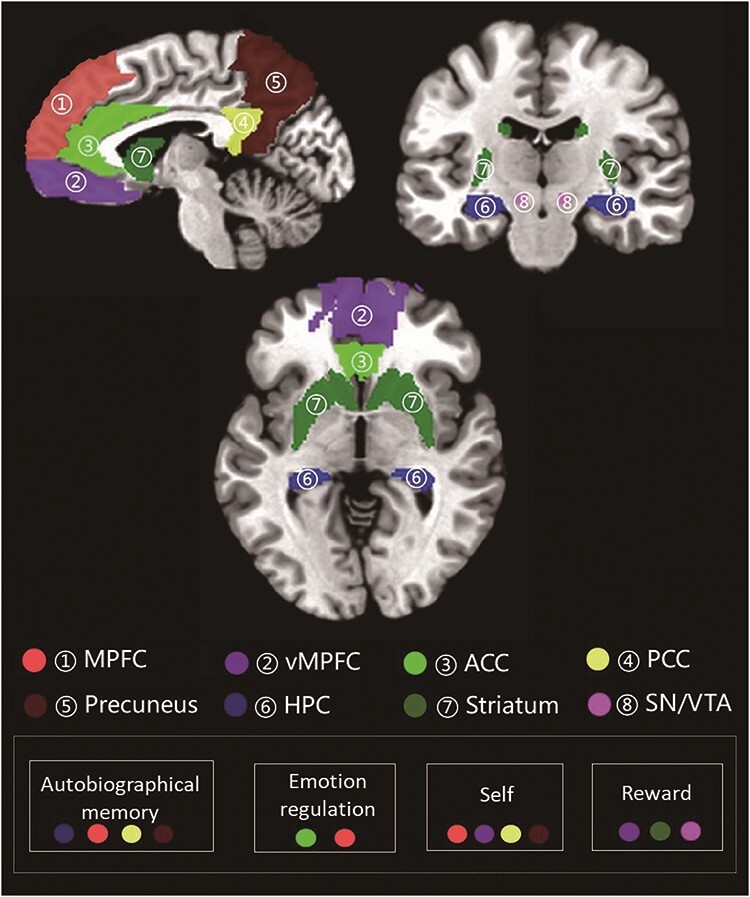

Experiencing emotionally motivating memories activates the amygdala, hippocampus, and areas in the MTL (medial temporal lobe) while the brain’s reward system increases activity in the basal ganglia and ventral striatum. Sensory information, from internal and external sources, is processed in the insula and the diencephalon (hypothalamus and thalamus) and all these emotional, sensory and regulatory signals interact, influencing higher order processing and information integration. The coordinated activation of all these regions is a key feature of learning, goal-directed behavior and nostalgia

LEARN MORE: Patterns of brain activity associated with nostalgia

Constant progress in neuroanatomical studies and brain imaging technology has given researchers greater insight into the where, when and how of cognitive functions like memory, emotion, and motivation.

We have identified specific regions involved in these processes as well as the presence of coordinating regions organized into functional networks. This kind of knowledge expands our understanding of the local and distributed connectivity required for particular processing tasks. The discovery of patterns of rhythmic brain activity has shown researchers that coordination is not only spatial but temporal too. The timing signatures of the synchronized waves of neural firing occur at specific frequencies for different types of brain activity and arousal levels. Interactions between different frequency brain waves support further cognitive functioning.

“Nostalgia involves neural substrates known to be engaged in self-reflection, autobiographical memory, emotion regulation and reward processing.”

— Ziyan Yang et al

LEARN MORE: Nostalgia and BRAINS!

Nostalgia induced seeking can be an impossible itch to scratch.

Some nostalgic feelings are very sweet with just a slight tinge of bitterness, whereas other nostalgic feelings are very bitter with just a tinge of sweetness. (Newman, 2020)

LEARN MORE: Locating nostalgia among the emotions: A bridge from loss to love

LEARN MORE: Nostalgia and well-being in daily life: An ecological validity perspective

How these feelings affect an individual or group’s well-being depends on the intensity and quality (valence) of the nostalgic stimuli and the context in which the nostalgia is cued.

Recent research suggests that experiencing nostalgia increases a person’s dominant, pre-existing mood and disposition. So it can prompt purposeful actions and hopeful pursuits when it occurs within a positive context.

Unfortunately, in an already negative context, the craving for a return to a physically or psychologically unattainable place can exaggerate negative feelings like hopelessness and grief. Misdirected distress can fuel maladaptive coping strategies. Many addiction scientists believe compulsive habits that lead to harmful consequences can evolve out of the most benign impulses if the reward system is highly activated and unchecked. Romantic love activates the same pattern of brain regions as drug use disorders and both compulsions feature emotionally charged, goal driven, pleasure seeking behaviors. Nostalgia shares this same pattern.

So what kind of habituation is nostalgia driving?

It seems to be urging us to reconnect with ourselves, revisit our origins and re-read key chapters from our personal narratives. Since our identity, our sense of self, is built on our history and our feelings about our experiences, this habit of continually re-examining the mental maps of our life may be the underpinning of personality maintenance. Where we’ve been, what we’ve done and who we did it with is all information that our brains expend significant resources to store and maintain for us to access so it must be important beyond just finding food and companionship. Nostalgia uses neurochemical rewards to preferentially promote the integration of past selves with the present self. Research on multicultural nostalgia shows us that self-continuity suffers when people feel disconnected from their past identities.

Nostalgia is the instinctual drive to stay connected with who we once were and it ensures that our past remains relevant to who we are now.

LEARN MORE: Editorial: Beyond Reward: Insights from Love and Addiction

LEARN MORE: Nostalgia and Acculturation

Many thanks to Journalism teacher Sarah Case and her students at Kennedy Middle School, and to my fellow outreach volunteers Mina Sattari and Jadyn Harris from Portland State University.