Post by Brooke Searle, regular Northwest Noggin outreach participant and undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

“Then after lunch it’s puzzles and darts and baking, papier-mâché, a bit a ballet and chess…”

— Rapunzel (from Disney’s “Tangled”)

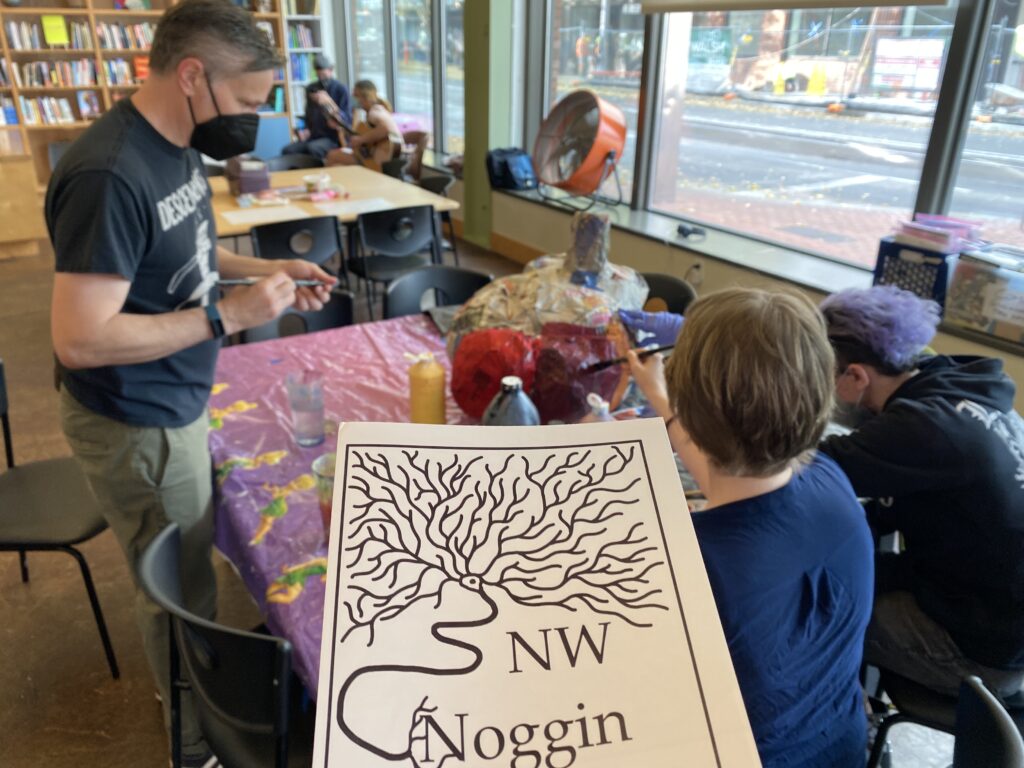

On two days in October, NW Noggin came to the extraordinary and inspiring houseless youth nonprofit p:ear with a new goal of creating a papier-mâché brain, and I volunteered for the task. The funny part about it is that I had to shape my brain or adjust my ways of thinking to be up for the challenge.

LEARN MORE: NW Noggin + p:ear

LEARN MORE: How to Make Papier Mâché

LEARN MORE: How to Create Papier Mâché (with pictures!)

Day One

Here is a thing about me: I usually create art alone with no deadline.

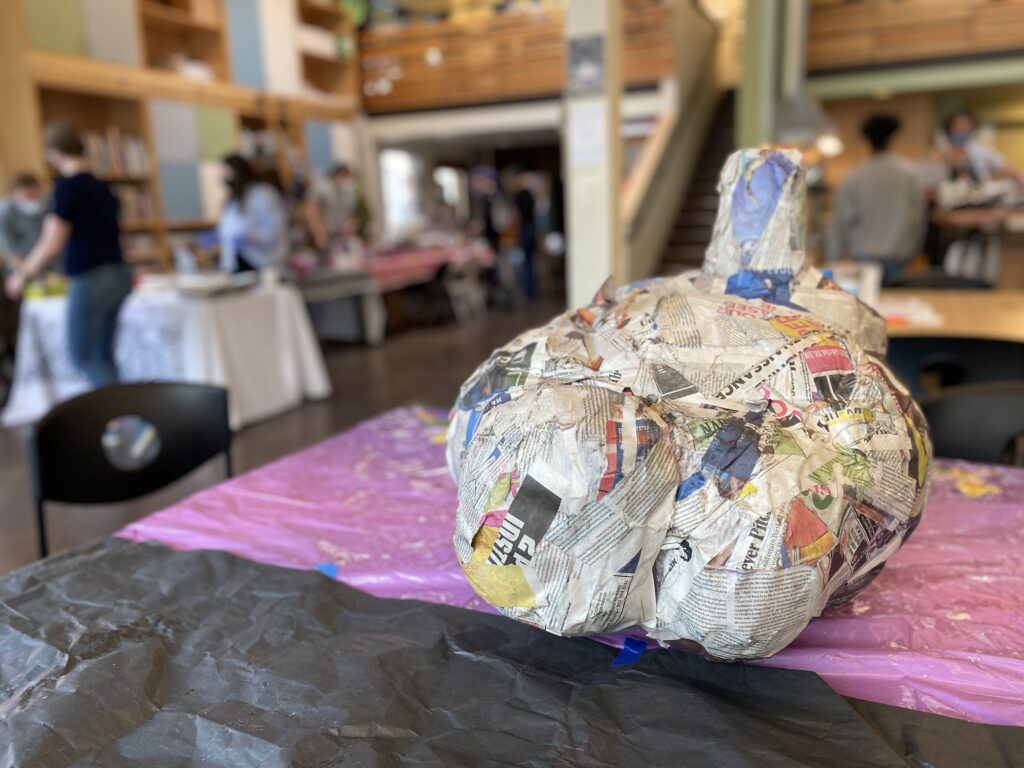

I can finish my own art pieces whenever I want, but not this papier-mâché brain. We had three hours on two days to work together and create a masterpiece. Okay, so it wasn’t much of a masterpiece. The right hemisphere was more significant than the left one (more on that later), but making it was fun and taught me new skills I wasn’t so good at before. In other words, it helped shape my brain.

You need paper for papier-mâché, so a couple of other NW Noggin volunteers and I went on an Old Town Portland scavenger hunt for newspapers. We started by finding newspapers to crumple up. You think this would be easy, but in the digital age, newspapers are printed less, and finding a newspaper bin isn’t as easy as you might guess. We looked by coffee shops and cafes with no luck. Then finally, we stumbled on a newspaper bin, headed back to p:ear, and began crumpling up paper to put into a trash bag.

LEARN MORE: Over 360 newspapers have closed since just before the start of the pandemic

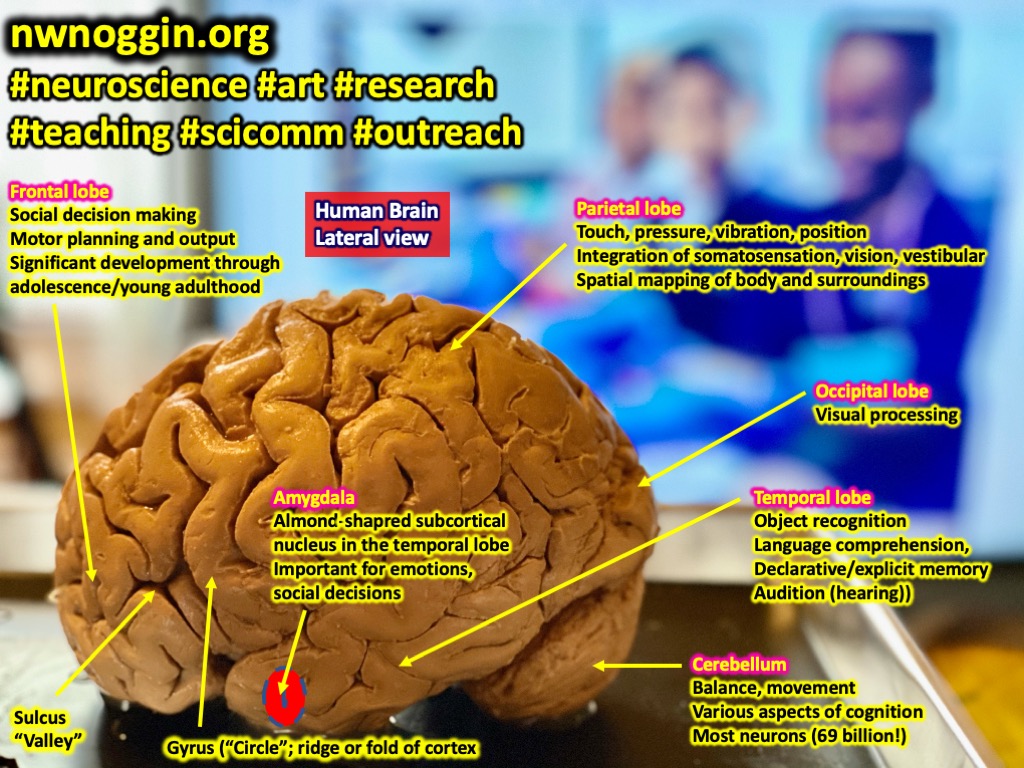

Once the trash bag was full of newspaper, we tied off the bag, so it was one big ball. Then we wrapped a long string around the middle of the plastic bag to divide up the two hemispheres of the brain – the left hemisphere and right hemisphere. We even tied a string around the back part of the brain where the cerebellum goes.

Now that I think about it, many things impacted our brains during this experience, as we attempted new tasks and tried out new skills. Neuroscientists have reported that a neurotransmitter known as dopamine is released in our brain if we do something novel, or new. I was doing something new. I had never created anything out of papier-mâché before and I had rarely created art pieces with others.

LEARN MORE: Dopamine Modulates Novelty Seeking Behavior During Decision Making

I think about the other tasks that our brains were doing. We were bringing something from our imaginations into reality. Second, we were doing this in a team setting, so we had to communicate our visions and our creative solutions with one another. Creating the brain together triggered areas of our minds involved in social decision-making. We use specific networks of linked brain regions, including a pathway from the amygdala to our frontal lobe when making social decisions.

LEARN MORE: Prefrontal-Amygdala Circuits in Social Decision-Making

This article examines how social decision making was once thought to be localized in one brain area, primarily the frontal lobe. Yet this is too simplistic, as complex social choices seem to occur through the actions of many brain regions working together. Making a papier-mâché brain at p:ear definitely meant working together, and using many parts of our brains, including frontal cortex and subcortical (“below” the cortex) structures important for our emotional experience and expression.

LEARN MORE: Neuronal Circuits for Social Decision-Making and Their Clinical Implications

LEARN MORE: Neural mechanisms of social decision-making in the primate amygdala

LEARN MORE: Breaking human social decision making into multiple components and then putting them together again

LEARN MORE: A brain network supporting social influences in human decision-making

And as we worked together, we could better come up with creative solutions together. One of those innovative solutions came from another volunteer, to attach an empty glue bottle to form the brain stem.

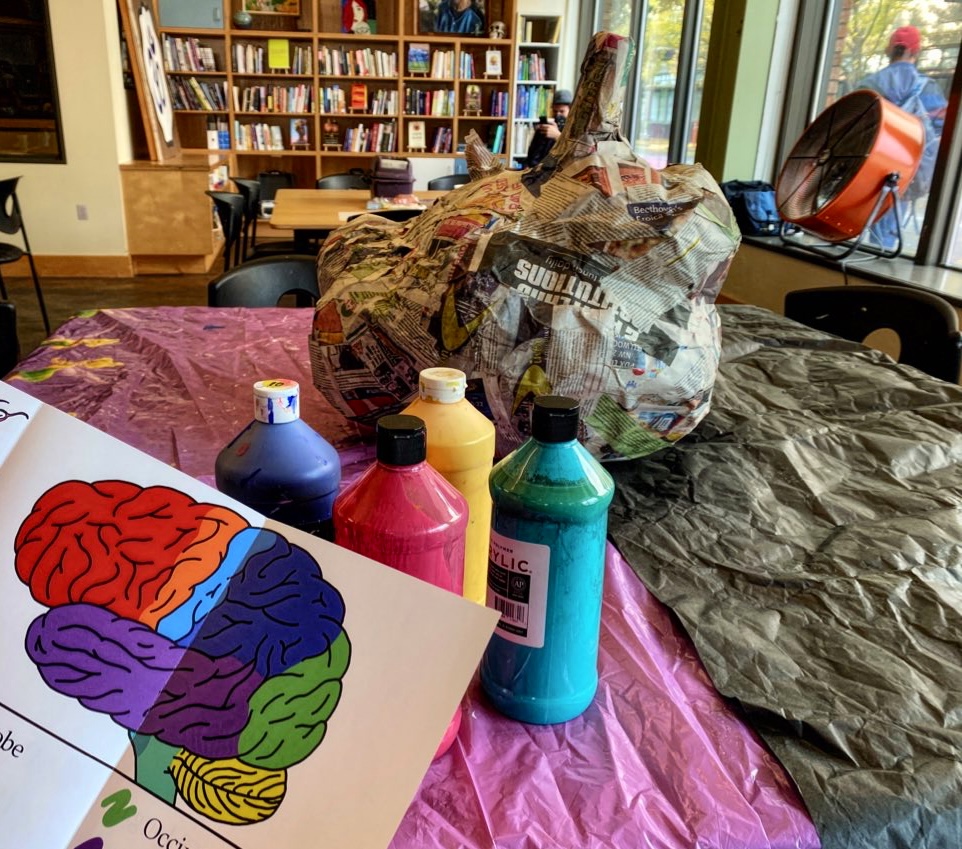

We then mixed glue and water, dipped newspaper strips in, and plastered the saturated newspaper strips directly on to the plastic bag. From Noggin Art Director Jeff Leake: “We didn’t measure the glue though we just mixed it with water. I think the ratio is somewhere around 3 parts glue to 1 part water but we just mixed glue with warm water until it was thick enough to stick to our fingers.” After covering the bottom portion of the bag (a.k.a. the brain), we had to cover the top part of the brain. To do this and allow the papier-mâché to dry, we turned on a fan and placed our “developing brain” on a bucket.

This was the part that was really cool, seeing our vision (that at that point was mostly in our imaginations) start to come to life. This was the part where all our brains were firing off dopamine as we anticipated rewards coming from our communication skills and teamwork. It was for me anyway; I remember being very excited. I found the newspaper brain to be fantastic.

Yet, once we turned our brain over, we realized that one hemisphere significantly larger than the other. At this point, our first day was almost up. So, this was but another practice in shifting my habits, from my tendency to make everything perfect to learning to let go and enjoy the process. So, I did just that.

We finished up day one of brain making and came back the following Thursday to finish our new noggin.

Day Two

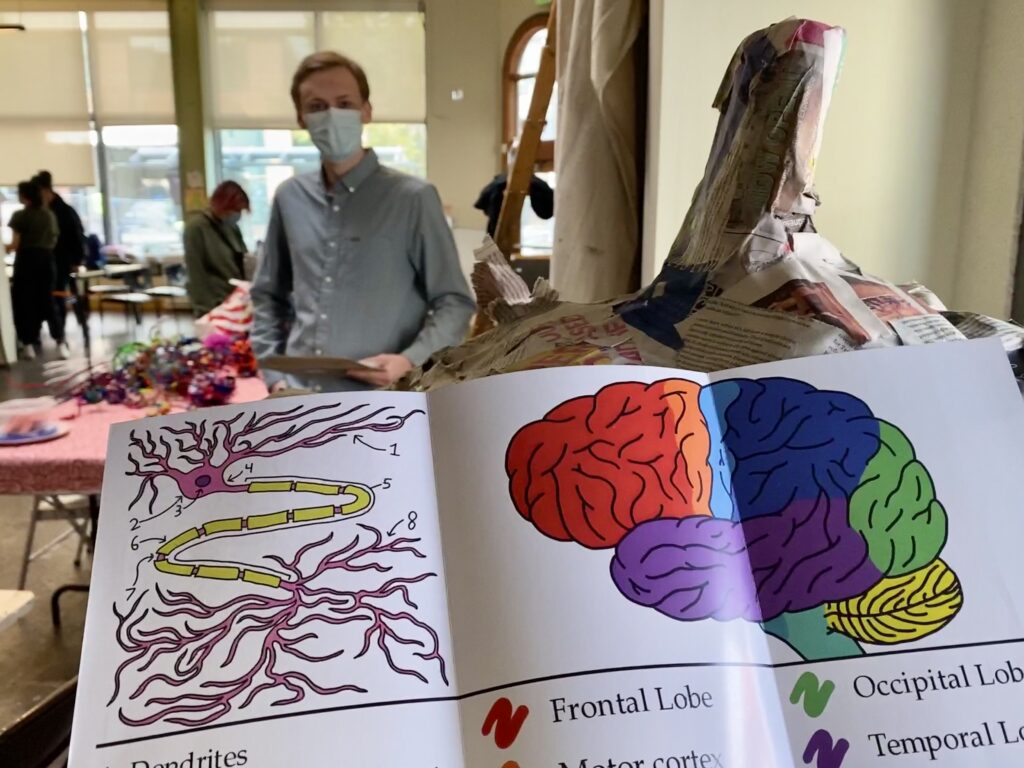

Day two was straightforward – painting the brain. And what could be more convenient than having another Noggin volunteer, fellow PSU undergraduate Roman Cimkovich, bring his colorful and informative new brochure on the brain for “painting the brain” day?

LEARN MORE: Neuroscience for all: Creating a Brain Brochure

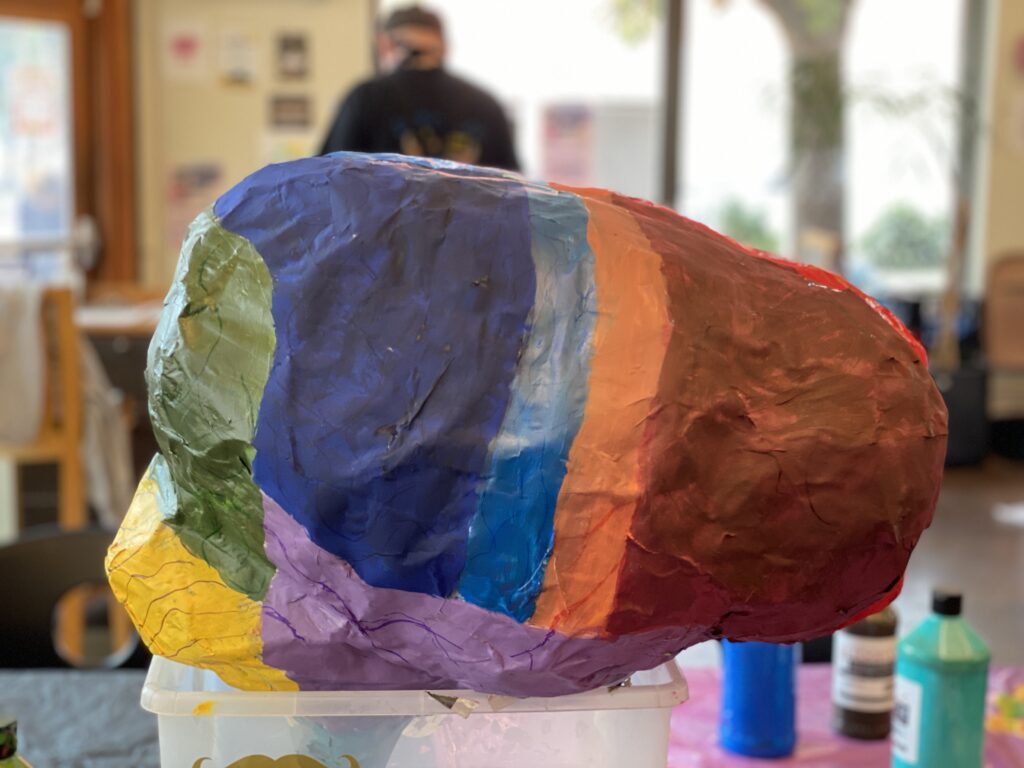

We decided to paint the brain regions the same colors as in the brochure.

We also chose to paint one side of the brain a little darker than the other side of the brain. This took some time and color-matching. Eventually our brain sort of looked like the brain on Roman’s brochure (emphasis on “sort of”).

We even had enough time to take some colored markers and draw in the gyri, or folds, of the brain.

We often joked about what kind of individual we were creating.

As you can see, our papier-mâché brain was lopsided. One idea we had was if someone’s brain had a larger right hemisphere, like our papier-mâché brain, maybe they’d be better at seeing the big picture, grasp the emotional aspects of what others are saying, or arrive easily at the point of a story. And if that person had a diminished left hemisphere, they could have trouble speaking or focus less on details.

LEARN MORE: Left Brain, Right Brain: Facts and Fantasies

What can I say, the papier-mâché brain was not perfect, yet I did enjoy it, and in fact, I can’t help but wonder if we continue making papier-mâché brains if “practice would make perfect,” so to speak. I can’t say we’d want to make a perfect papier-mâché brain, but it would be fun to create again and watch our skills improve.

In cognitive neuroscience, they talk about how practice helps complex tasks to become easier over time. Every time we do a task, neurons in our brains communicate with one another to change and strengthen specific neural networks. And the more often we do the task, the stronger the connections become.

LEARN MORE: Does practice really make perfect?

LEARN MORE: Experts bodies, experts minds: How physical and mental training shape the brain

LEARN MORE: What’s the Connection Between Art and Brain Development?

I learned a lot about how to papier-mâché and create art with other people. I grew some friendships, and not only did I get to shape a papier-mâché brain, but I got to shape my brain. I walked away, shaping a papier-mâché brain and my own.

Join us at NW Noggin. We’d love to see you!

Check out our homepage!