“This is so cool! I love hands on stuff – even hands on BRAINS!”

—3rd grader at Washington Elementary in Vancouver Public Schools

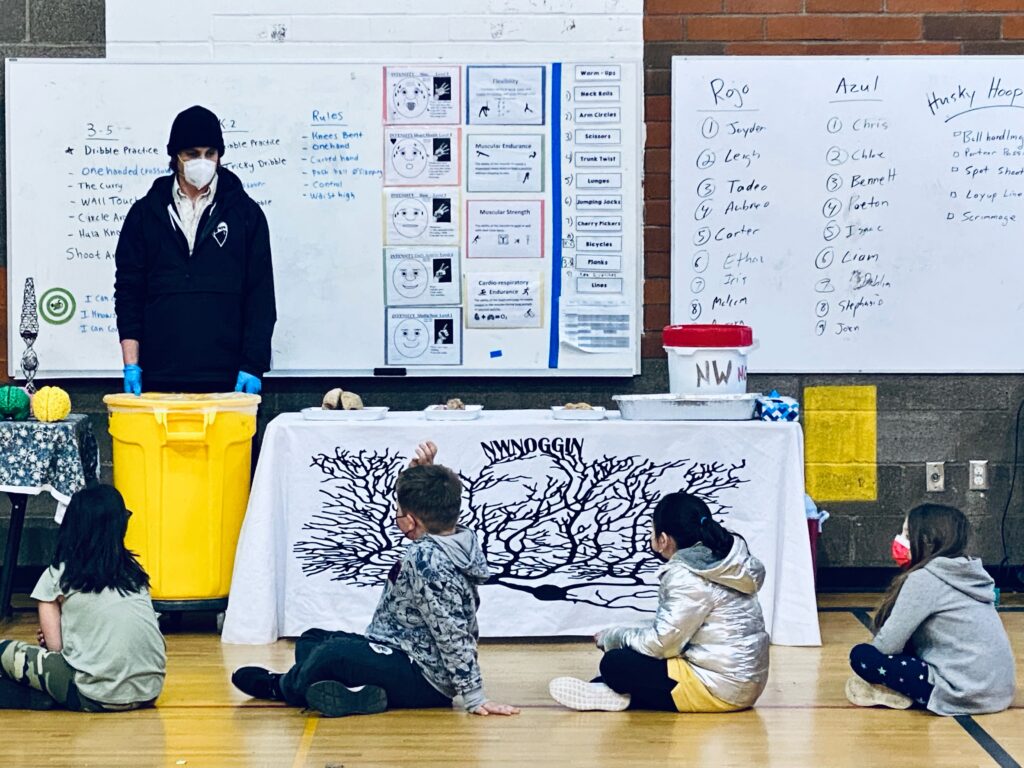

On a brisk, chilly, windy morning, with temps hovering around freezing, some awesome and talented undergraduate and graduate students arrived early at Washington Elementary in Vancouver to share their fascination for neuroscience research and art!

Arielle Isakharov joined us from Oregon Health & Science University, along with Bradley Marxmiller (an NIH BUILD EXITO student at Portland State University currently interning in a lab at OHSU), and Melissa DeMoura, Britta Harbury, Alex Heinrich, Ben Bolen and Rose Jardine from PSU. Ben and Rose are also officers in the Portland State University Neuroscience Club!

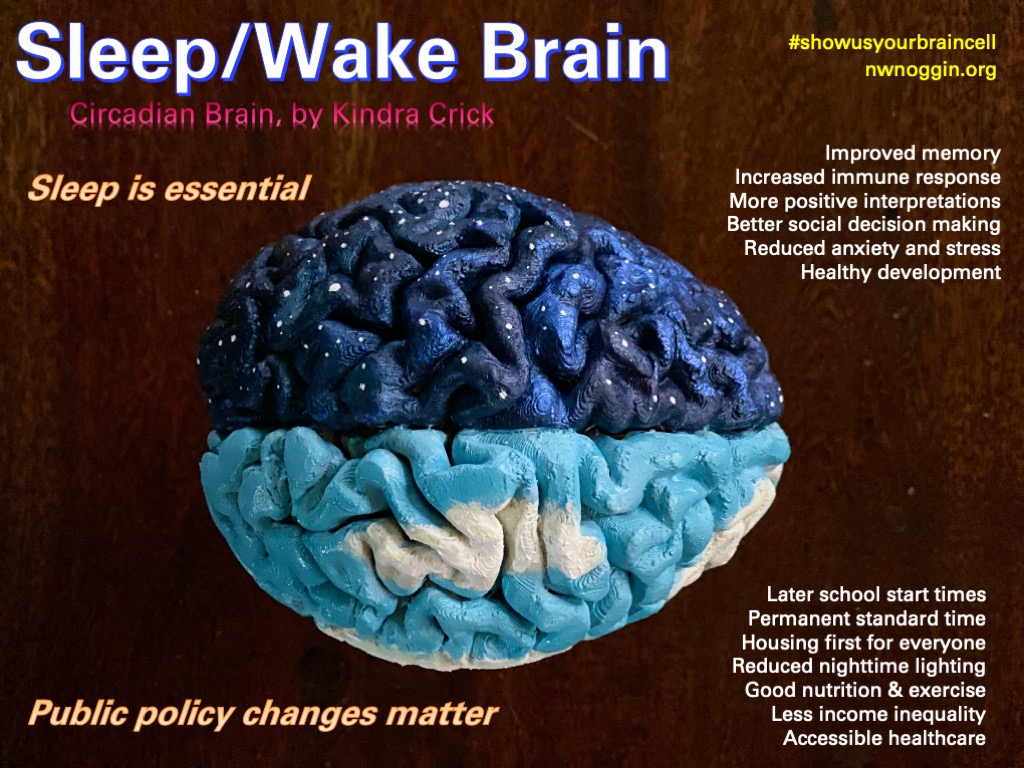

We were grateful to arrive in sunlight, a few weeks before our region takes the unnecessary and dangerous plunge back into morning darkness with the March 13 arrival of “Daylight Savings” Time. No daylight, of course, is saved – we just have to get up an hour earlier in the dark, which leads to clearly documented declines in health and wellness.

THE RESEARCH IS CLEAR: Permanent Standard Time is best for our brains.

LEARN MORE: The US wants to increase sleep deprivation and winter misery

LEARN MORE: American Academy of Sleep Medicine calls for elimination of daylight saving time

LEARN MORE: Why should we abolish Daylight Saving Time?

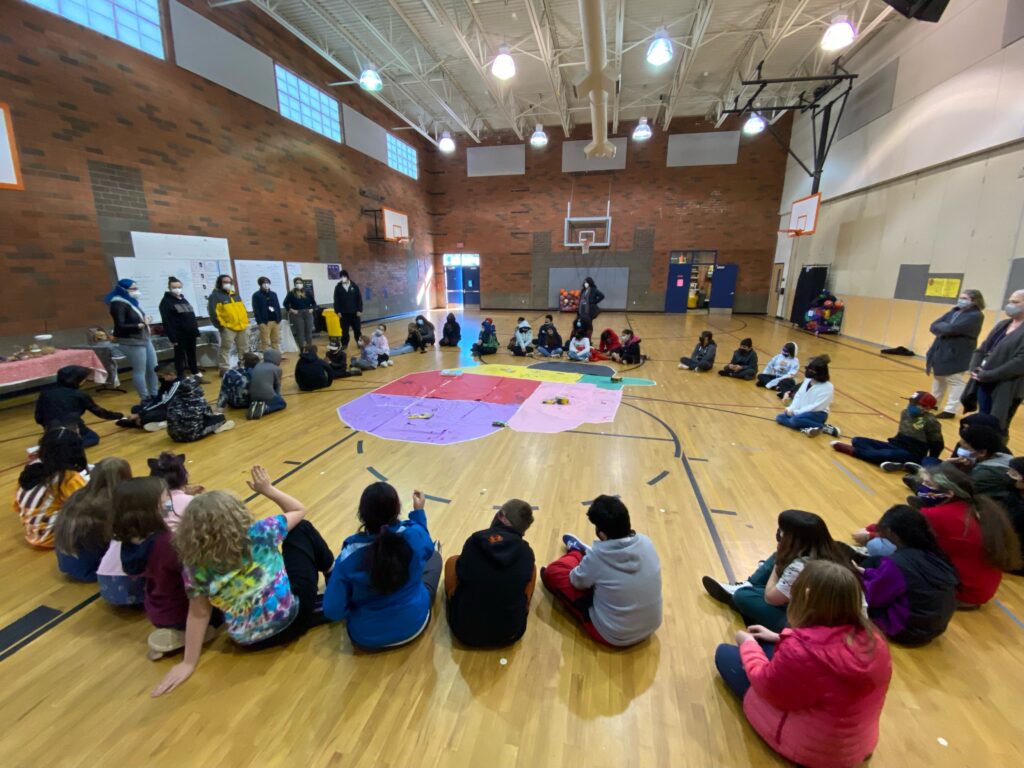

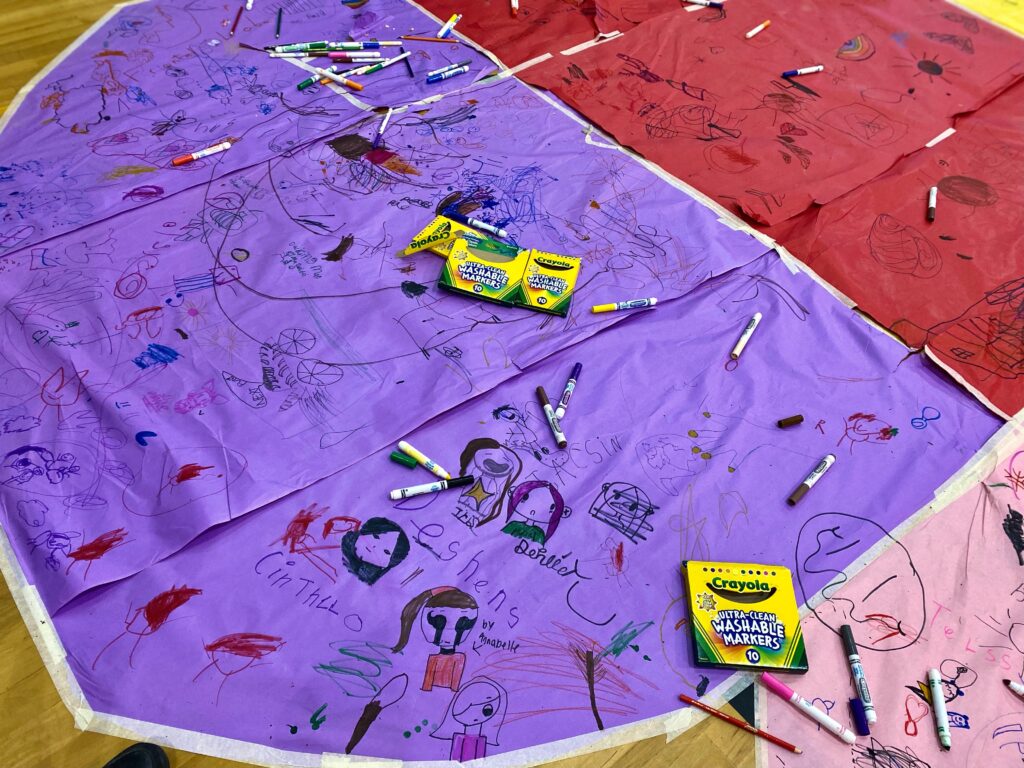

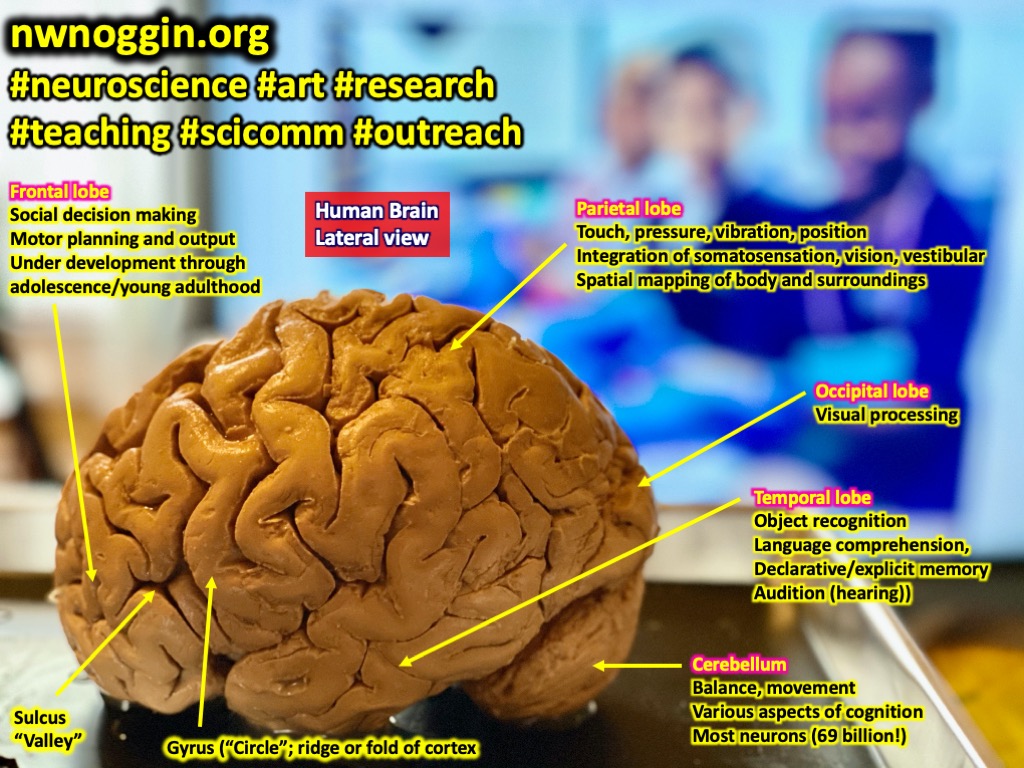

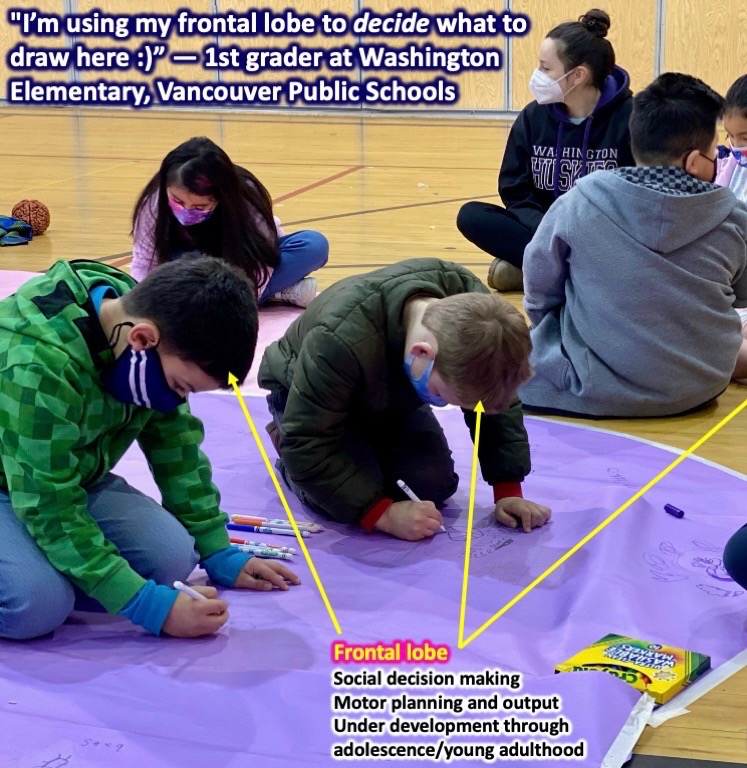

Acknowledging the cold temperatures, biting wind and kindergarteners scheduled that morning, we pivoted from a shaded outdoor location to a well-ventilated gymnasium – with doors propped open at both ends there was a substantial draft! The shift allowed us to quickly tape a large “brain map” on the floor, with bright colors delineating the cortical lobes, brainstem and cerebellum. Our volunteers introduced themselves and described these various brain regions and what they do.

LEARN MORE: Northwest Noggin Brain Map Project

Students Have Questions

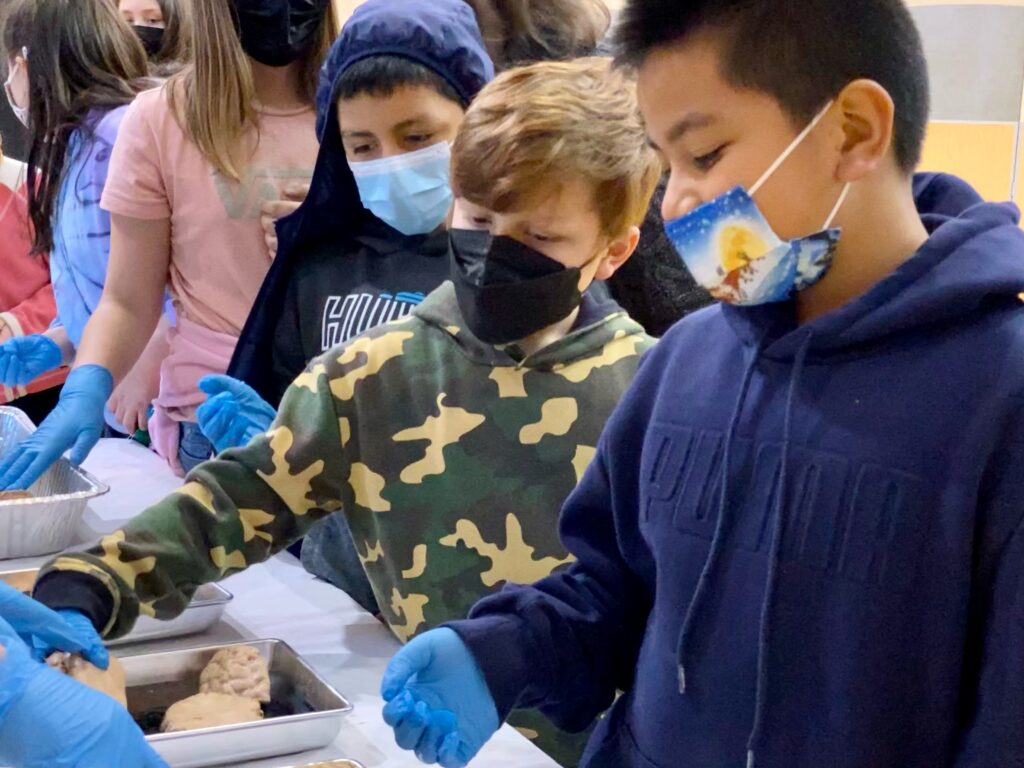

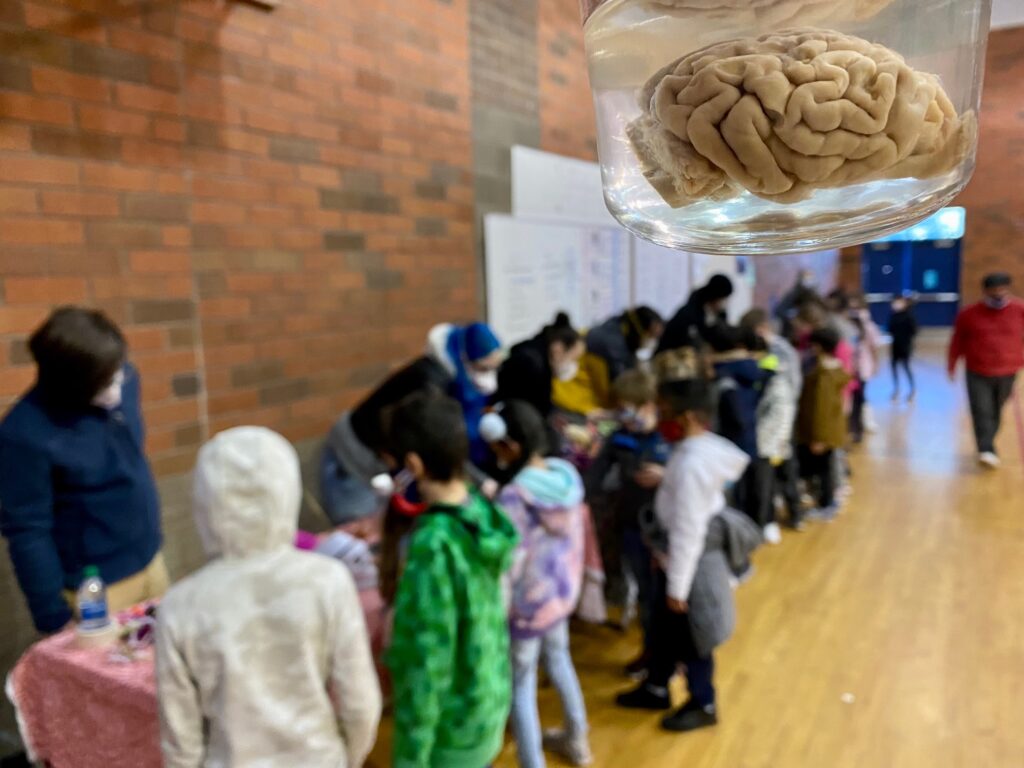

We also examined real brains and drew our own visual interpretations of what various brain regions accomplish, but it was the questions from over 300 K-5 students that drove the day’s agenda!

We are always struck by what people already know about brains, and what they want to discover, and the excitement, engagement and enthusiasm that results from being acknowledged and heard.

Northwest Noggin is thankfully not a canned institutional marketing effort that relies on memorized “elevator pitches” (we learned all about that approach here). We do not deliver boring corporate lesson plans (for profit) aimed at subjecting students to boring corporate tests (for profit), with every genuine piece of interesting, relevant and motivating information softened, redacted or banned.

Our undergraduate and graduate volunteers clearly love these genuine, student-driven experiences, and enjoy getting challenged by compelling student interests and ideas. We thrive on listening and sharing our own stories from labs and classrooms where they potentially (and quite often!) intersect.

So check out these questions!

What were dinosaur brains like?

The field of paleoneurobiology examines casts of the interior of ancient skulls (known as cranial endocasts) to determine the volume and potential structures of extinct animal brains, from hominids (like close human ancestors) to dinosaurs!

LEARN MORE: Are endocasts good proxies for brain size and shape in archosaurs throughout ontogeny?

LEARN MORE: Endocranial anatomy of the ceratopsid dinosaur Triceratops

LEARN MORE: First palaeoneurological study of a sauropod dinosaur from France

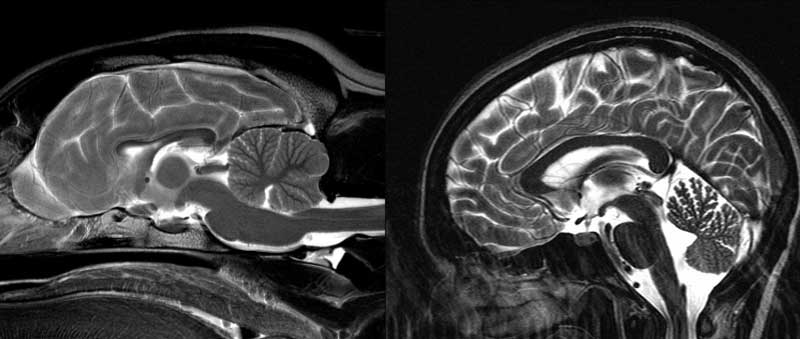

Are dog brains like our brains too?

“…we can see from an MRI of a dog brain that even though it is smaller than a human brain, all of the same basic structures are present. This is true for large regions like the cerebral cortex and the cerebellum, as well as for smaller, subcortical structures like the brainstem, hippocampus, amygdala, and basal ganglia, which have important roles in movement, memory, and emotion.

“Dogs also have large olfactory systems, comprising about two percent of the total brain weight (compared to 0.03 percent in humans). Where dogs fall short is in the cortex. Apart from being smaller, there are fewer folds, which means less surface area and fewer neurons. The frontal lobe, which in humans occupies the front third of the brain, is relegated to a paltry ten percent in dogs…”

LEARN MORE: Decoding the Canine Mind

LEARN MORE: Dogs Have the Most Neurons, Though Not the Largest Brain

How do you get the brains out?

An important question! Our brains are well-protected, both by bony skulls and a thick leathery sack known as the dura mater (or “tough” “mother”), one of the meningeal layers that surround our brain and spinal cord. You can learn more about where our noggins come from at the link below.

LEARN MORE: A BioGift of Brains

LEARN MORE: Cross-Country Noggins!

What are those wrinkles and bumps on the brain?

The outer surface of the brain is known as the cortex (“bark” in Latin), and is a sheet of multiple layers of interconnected brains cells, including neurons and glial cells. In some animals, like rats and mice, the cortex is smooth, but animals like dogs, raccoons and humans have a wrinkled cortex. A gyrus is a surface ridge or fold, while a sulcus is a valley, where the cortex bends below the brain’s surface.

The wrinkling allows for MORE cortex to fit inside our skulls.

“I want to study brains – AND I want to be an organ donor!”

—4th grader at Washington Elementary

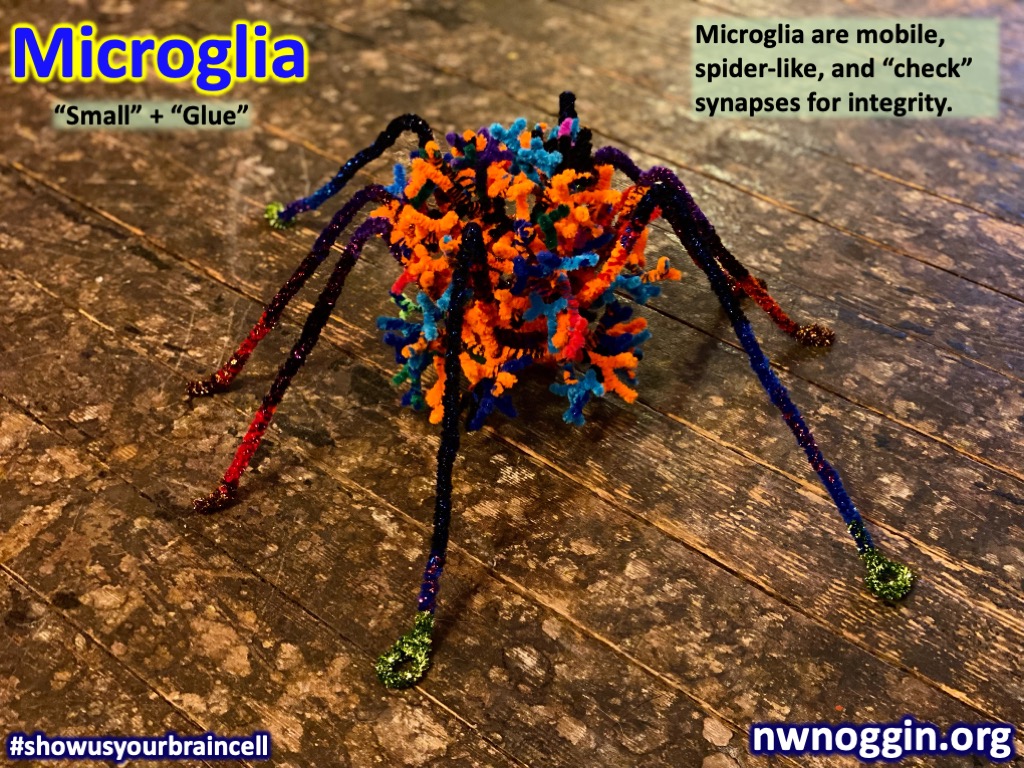

Do the “spider cleaners” fight coronavirus?

One of our pipe cleaner brain cells was the spider-like microglia, a critical component of the immune system in our brain and spinal cord. Microglia move about our web-like brains, touching synapses, the points of near contact between neurons. If they find something they don’t like, including cells infected by viruses, they’ll literally hulk up and attack, breaking them down for removal!

Several kids dubbed them the “spider cleaners.” And in some cases, the over-activation of microglia (too much cleaning) might worsen the neurological symptoms of COVID-19.

“We discuss how microglia may be involved in the neuroprotective and neurotoxic responses against CNS insults deriving from COVID-19. We examine how these responses may explain, at least partially, the neurological and psychiatric manifestations reported in COVID-19 patients and the general population.”

LEARN MORE: Microglia Fighting for Neurological and Mental Health

LEARN MORE: Microglial Implications in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19

LEARN MORE: COVID-19-related neuropathology and microglial activation

LEARN MORE: The link between microglia and the severity of COVID‐19

So many MORE questions!

“Ok because of you guys I want to study neuroscience.”

—5th grader at Washington Elementary

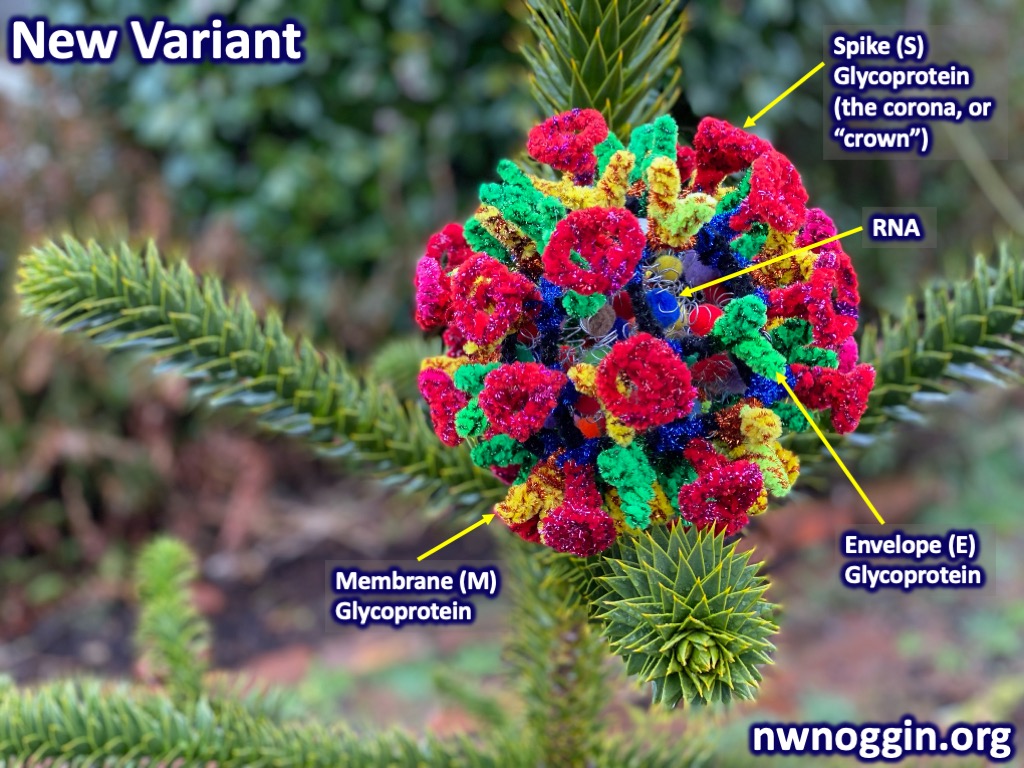

What are the spirals inside the coronavirus?

How does the brain work?

What are headaches?

Why don’t you see your nose?

Why don’t I feel my clothes?

Do you think our brain changes with the environment?

How does a baby’s brain know things?

What happens when you lose your sense of touch?

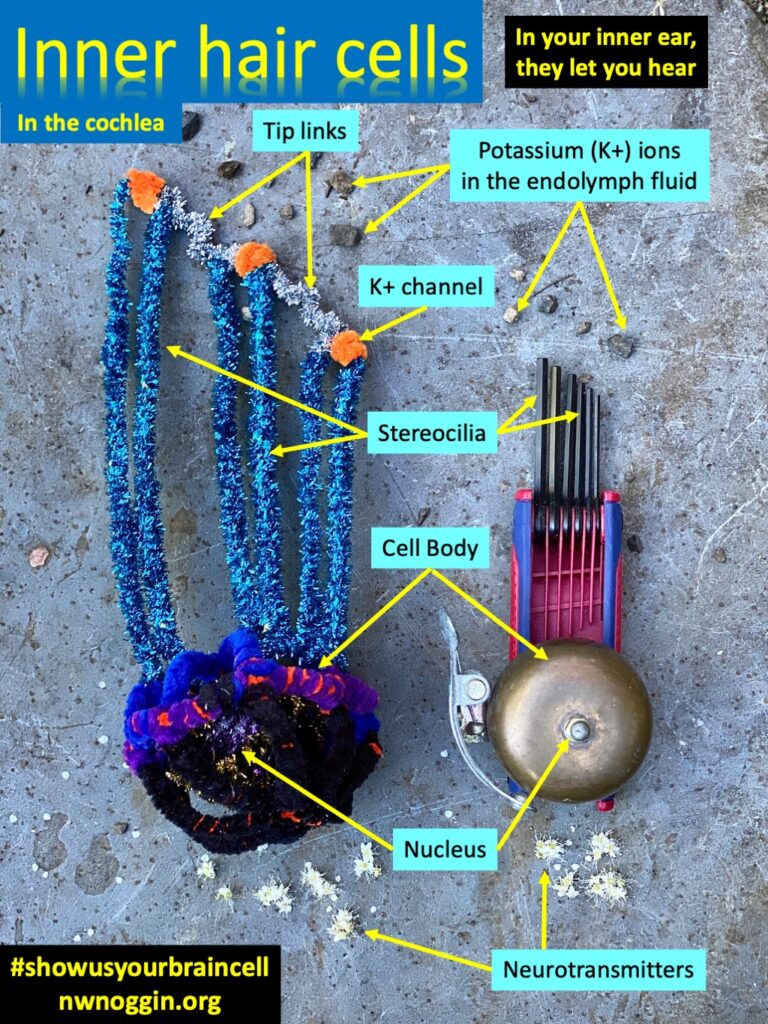

What parts of the brain are involved in auditory processing disorder?

There is still apparently significant debate over whether a single “auditory processing disorder” exists, given the complexity of the relationship between the sensory detection of sound waves by specialized neurons known as inner hair cells, and the subcortical/cortical networks involved in the conscious, perceptual experience of what we hear.

“It may be impossible to separate fully the sensory and cognitive components of hearing. And the separation becomes more difficult as stimulus and task complexity become increasingly realistic. To make a verbal or other report of what an individual hears it is necessary for a sound or its neural representation to pass through the various elements of the middle ear, cochlea, brainstem, midbrain, thalamus, auditory cortex, the many multimodal parts of the cortex with their heavy, bidirectional interconnectivity and, finally, the motor (action) centers and their effector systems that all play a critical role in even the most simple auditory-verbal tasks.”

LEARN MORE: Auditory processing disorder (APD)

Are you Bill Nye the Science Guy?

Will robots ever have the exact same brain connections as humans?

FROM Ben Bolen @ Portland State University: “In short, no. The exact same connections would require the exact same cells and we can’t just get a dead brain and make the synapses start firing again. There is some research on bio-inspired synthetic neural pathways that approximate brains like what I study at PSU. Besides that I don’t see how it would work. However, “never say never” as the saying goes.”

LEARN MORE: Bio-circuitry mimics synapses and neurons in a step toward sensory computing

LEARN MORE: Synthetic biology routes to bio-artificial intelligence

LEARN MORE: Bioinspired Networks of Communicating Synthetic Protocells

LEARN MORE: BIOMEDICAL SIGNAL PROCESSING LAB @ Portland State

If you want to stop thinking about something how do you get rid of it forever?

What happens if you have no amygdala?

Where is creativity in the brain?

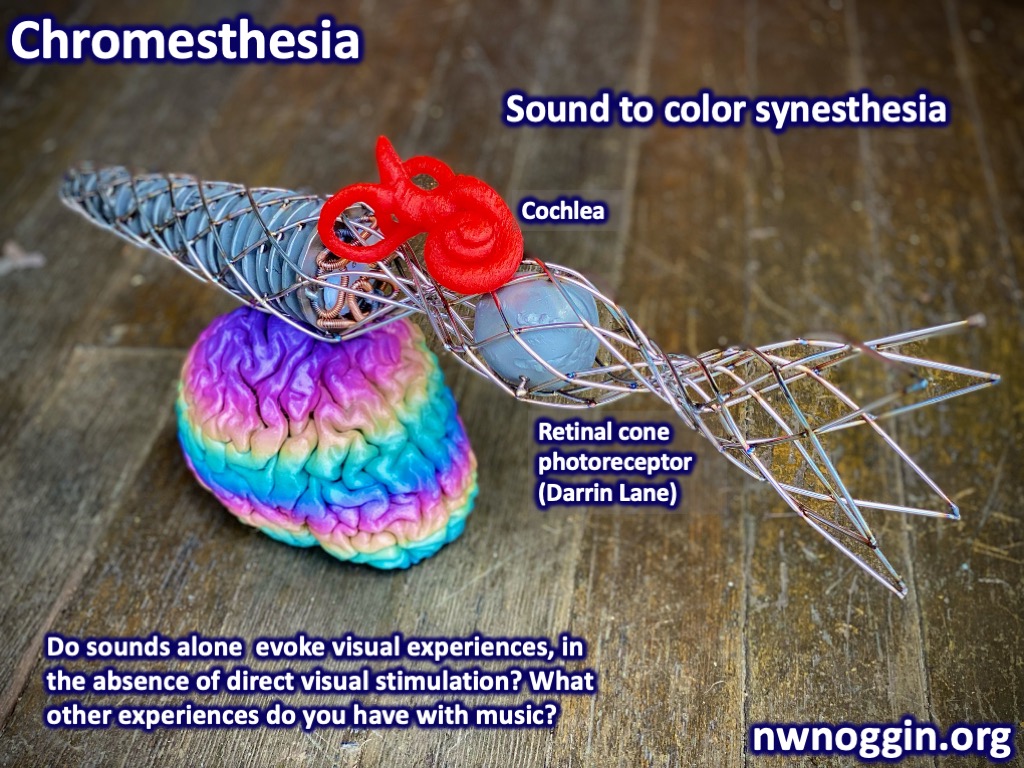

Is it true that you can see sounds?

LEARN MORE: The Qualia in Chromesthesia

“I’m only touching a brain because I want to be a surgeon!”

—3rd grader at Washington Elementary

“I want to be like you guys when I grow up!”

—3rd grader at Washington Elementary

STAY TUNED: We’ll keep updating responses to student questions!

THANK YOU

“Are you the brain people?! My kids cannot stop talking about the brain people!!”

—Parent driving by as we loaded up the car with brains at Washington Elementary

Our sincere thanks to all the students, teachers and staff at Washington Elementary, and our own Northwest Noggin volunteers, for sharing your questions, insights and enthusiasm for brain research and art!