Post written by Kayla Townsley, OHSU (a recent graduate of Portland State University and an NIH BUILD EXITO scholar)

“Hunger only for a taste of justice

Hunger only for a world of truth”

–Tracy Chapman, All That You Have Is Your Soul

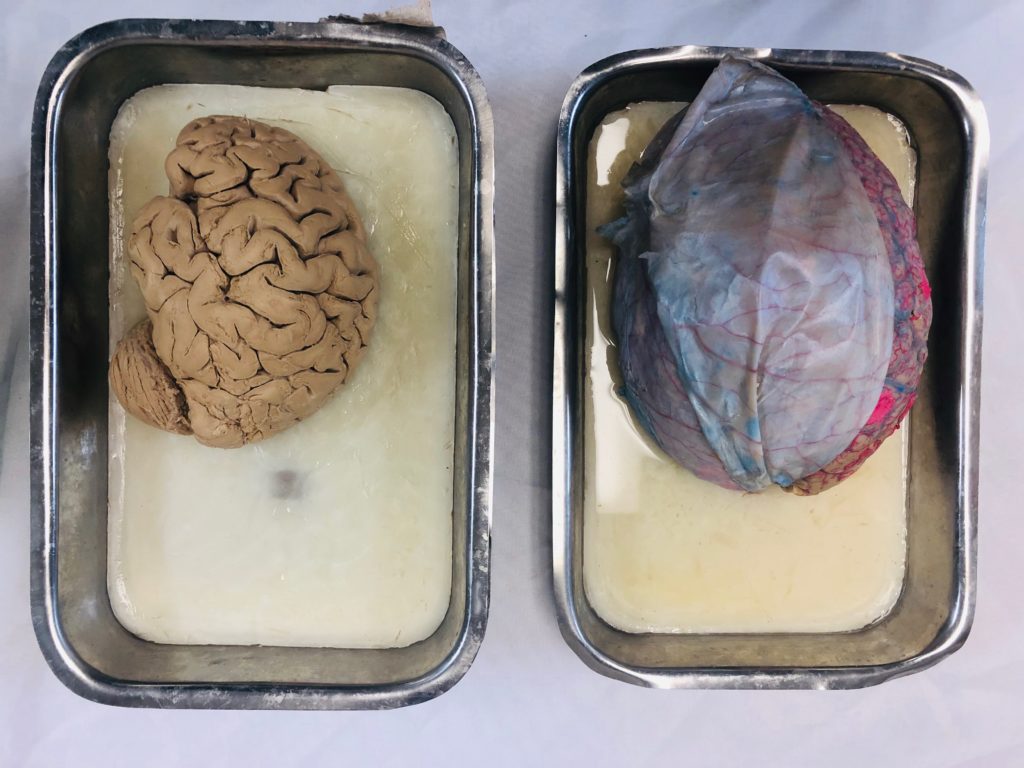

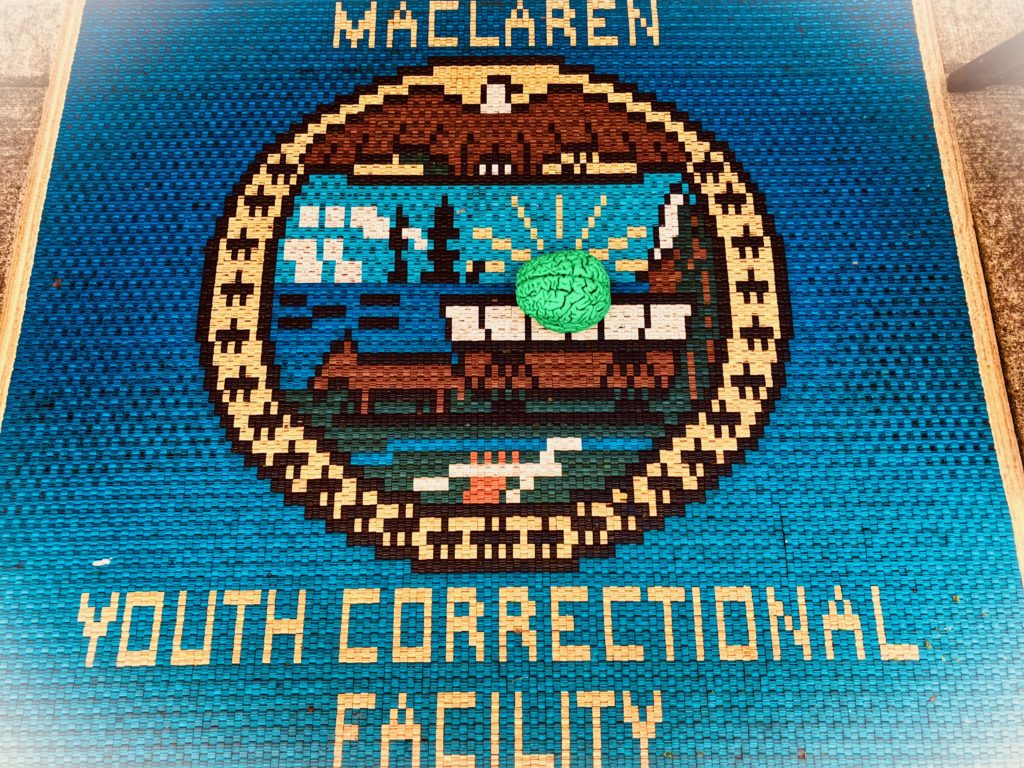

When I walked through the doors of the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility in Woodburn, Oregon I was nervous, anticipating difficult questions from the youth and hoping I could answer them adequately. Of course, their astute curiosity meant that my response was often “we don’t know yet, but researchers are asking those same types of questions.” Although it may not seem like it, neuroscience is a relatively new field, and with the vast complexity of our brains and nervous system, we are continually working to uncover even the simple mechanisms underlying relatively straightforward behavior. As we begin considering more complex behaviors like drug addiction, biases, impulsivity and the influence of our environment on these outcomes, it becomes increasingly more difficult to unravel. Despite this, the field has also made significant progress since its conception and recent developmental data provide new insights into the stages of brain development, especially with regard to adolescents.

LEARN MORE: Corrections, Bias & Brains

LEARN MORE: At risk of being risky: Teenage brains & Oregon’s Measure 11

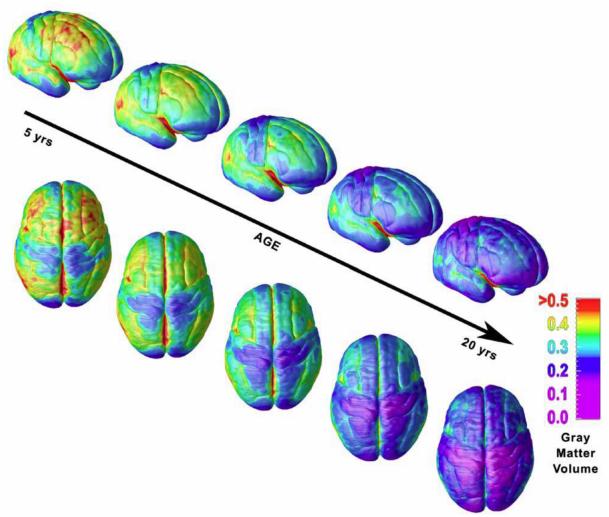

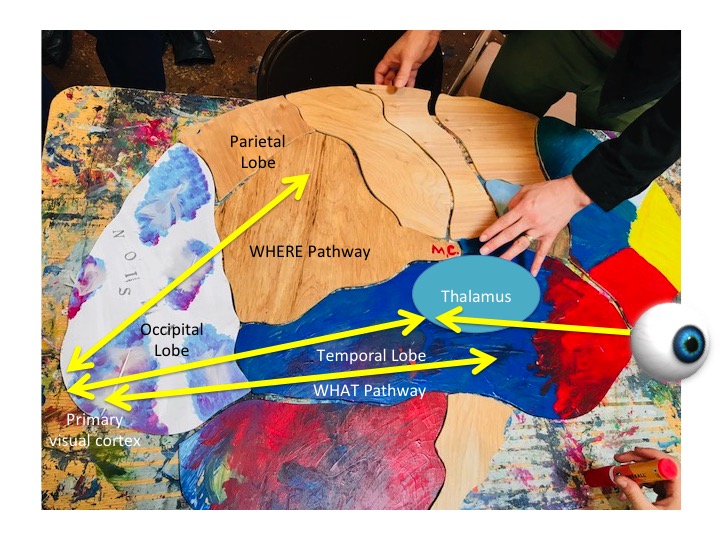

For example, from about 11 years up until our mid-twenties our brains are still under construction and a significant amount of neuronal pruning is occurring, specifically in the pre-frontal cortex, a brain region crucial for reasoning and social decision making. This pruning out of synapses and cells, although reducing the number of neurons, also strengthens specific connections and which connections are “tagged” to grow stronger depends largely on experience—learning through trial and error. Similar to lifting weights to build muscle, the more we use a certain way of thinking, the more we give-in or demonstrate discipline, the more we follow rules or break them, the stronger the connection between the cells coordinating that action in our brain becomes, and the more likely we are to continue in that behavior. Also, during this time of life, impulsivity is generally increased because of elevated levels of dopamine in the brain’s reward system. It is thought that this is actually evolutionarily beneficial, because it pushes teens to make more emotionally based, impulsive decisions, naturally venture off on their own, feel the consequences of their mistakes, and learn from personal experience. This experience then influences how the brain develops and how we learn to act and react in social contexts once adults.

Experiencing trauma, isolation, or exposure to drugs during this period of development can negatively influence a youth’s trajectory and is one reason why minimum sentencing laws, such as Measure 11 here in Oregon, are not only harmful to the incarcerated youths, but to society as a whole, contradicting what the science suggests in terms of healthy development and successful reintegration.

LEARN MORE: Adolescent Development of the Reward System

But equally concerning is how the current system sets these young people, especially those of color, up for future failure—almost ensuring recidivism even for those only experiencing brief juvenile sentences, but especially for those charged with felonies during their childhood and kept in the system into adulthood. When released, they often lacked rich social environments that would have allowed for “healthy” development and find it difficult to integrate into society’s quotidian routine. A conversation I had close to the end of our visit with a young man especially demonstrates these difficulties and how the current system is not only failing our youth, but actually setting them up for a predominately incarcerated life.

LEARN MORE: The New Jim Crow

When we first started talking he asked me about where I went to school, and how I got into neuroscience, and I asked him about his hobbies and his hopes for the future. He told me he was being released in a few months and focused on finding an apartment and job as soon as possible. We then talked about how he had thought about taking college classes at Portland Community College so he could provide more for his daughter. I think anyone could relate to these aspirations, but what struck me most was when he started asking for my advice on apartment hunting and how often you have to sign a lease. He seemed surprised when I told him that you usually have to go through background checks and pay application fees just to be considered; not to mention have steady employment, references, or a co-signer. Although in Portland finding affordable, equitable housing is difficult for anyone, for people slapped with the “felon” label it can become near impossible.

For example, a Princeton study in 2003 found that employers are only between one-half and two thirds as likely to consider applicants with a criminal charge than those without one. And in neighboring Washington state, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) received 441 complaints under “records” between 2000-2010, with most listing the barriers people experienced with regards to employment or housing due to their criminal record. In fact, doing any task towards providing for yourself, whether that’s looking for housing, job hunting, or applying for loans for higher education, is seriously impeded for folks charged with a felony, even if it was a crime committed during their adolescence.

LEARN MORE: The mark of a criminal record

LEARN MORE: No Second Chance: People with criminal Records Denaied Access to Public Housing

LEARN MORE: Boxed In: How a Criminal Record Keeps You Unemployed for Life

But the disadvantage these youths face go far beyond the stigma of their charge. Inside these facilities, many youth lack opportunities to gain crucial life skills, vocational training, community support, or the experiential knowledge that we typically gain through social interactions at school or at work in our teenage years.

The Janus Youth Program Hope Partnership, whose organizer Kathleen Fullerton reached out to NW Noggin and its volunteers to invite us to MacLaren, works with incarcerated young men to provide community connections, workshops from community members, and transition services that encourage positive and normalized youth development to better prepare them for independence outside of the system. These types of programs are working tirelessly to help them fill the gaps and overcome the obstacles placed in front of them by their life situations, but they can only work to the extent that the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA) allows.

LEARN MORE: The Janus Youth Program Hope Partnership

Beyond these internal programs, what we need is a rewiring of the juvenile justice system and how we think about rehabilitation and reintegration. Given the extensive evidence from the developmental sciences, fair sentencing in the justice systems needs to be reimagined based on the consideration that adolescents differ from adults in many of their cognitive and behavioral attributes. Here in Oregon, where there is now one of the highest rates of youth incarceration in the country, we can start by repealing Measure 11, a ballot initiative passed during the 1990’s sensationalism over teenage “super-predators.” To reduce recidivism, promote rehabilitation, successful reintegration and allow for healthy maturation for young Oregonians, current justice policies must be critically evaluated in the context of our modern society and undergo informed, evidence-based reform.

LEARN MORE: Rewiring juvenile justice: the intersection of developmental neuroscience and legal policy