“It’s not stress that kills us, it is our reaction to it.” -Hans Selye

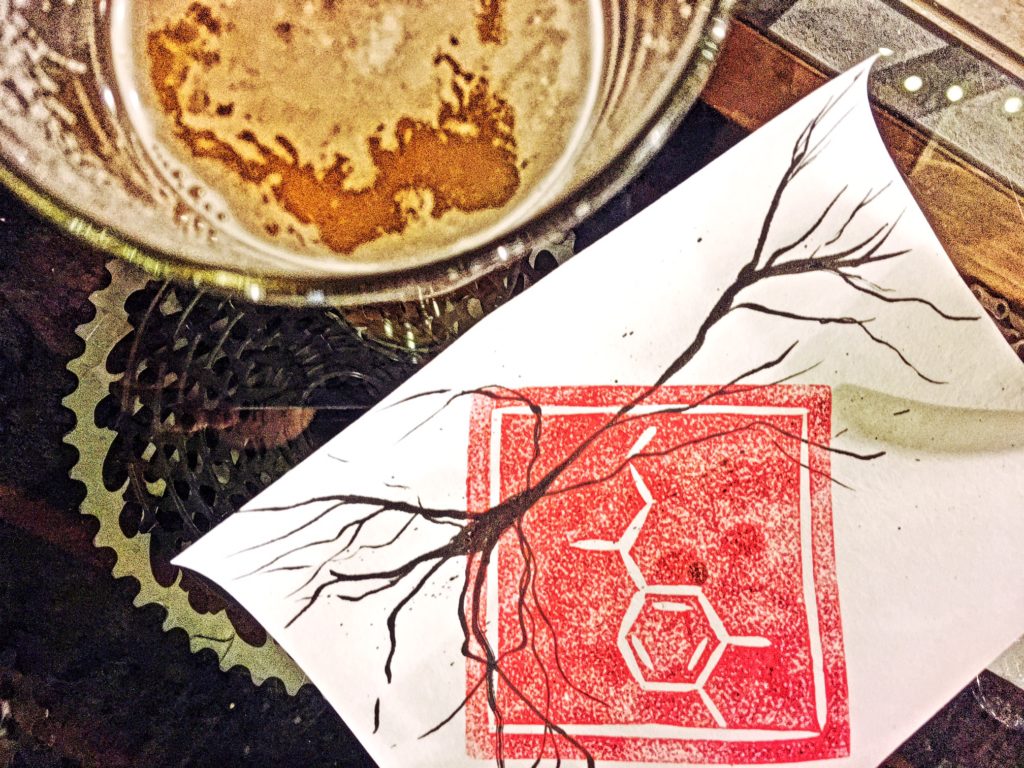

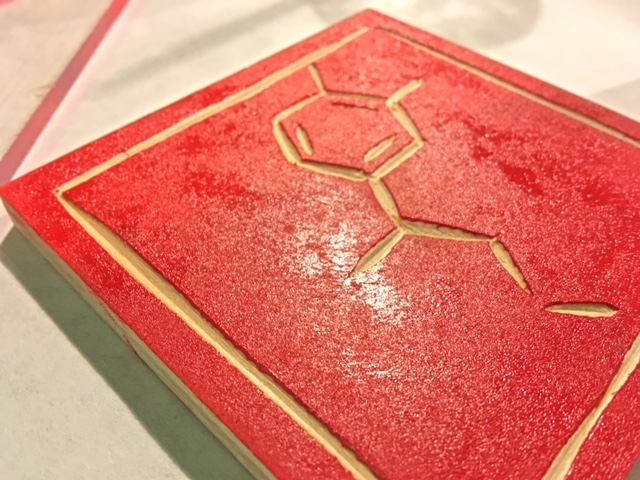

“Inspired by the HPA axis,” by Kanani Miyamoto

Final exams, politics, holidays, implicit and explicit bias – it’s no wonder people feel stressed these days. Yet stress can also be beneficial, and there are steps we can take to gain perspective and balance, and improve our physical and mental health…

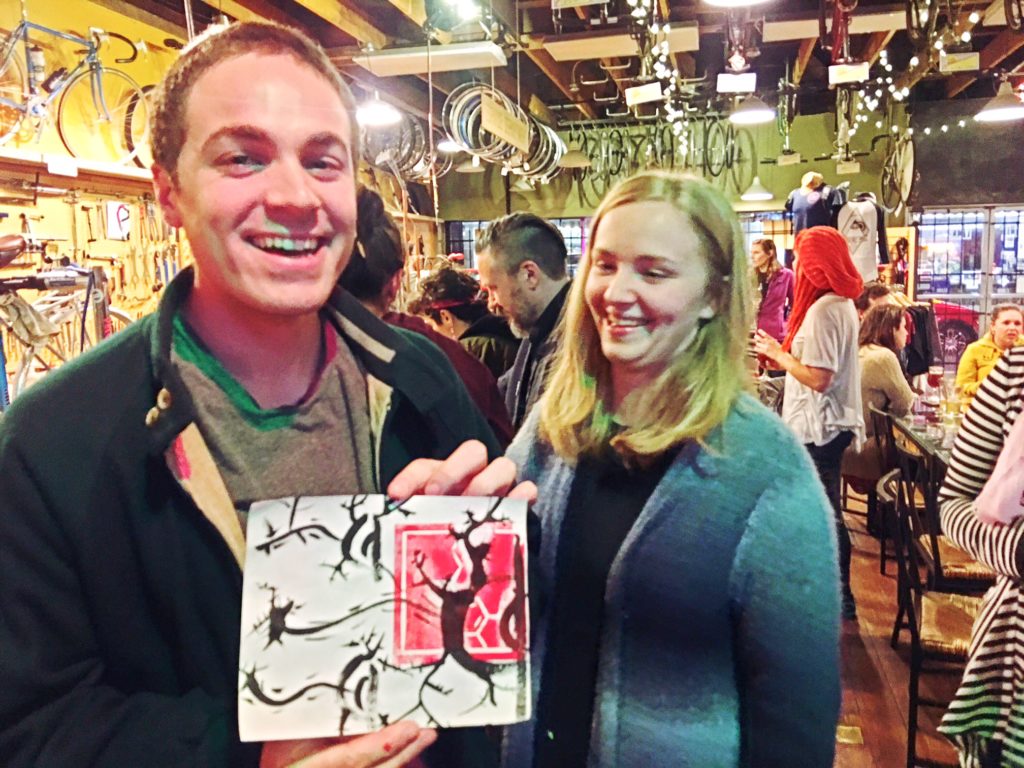

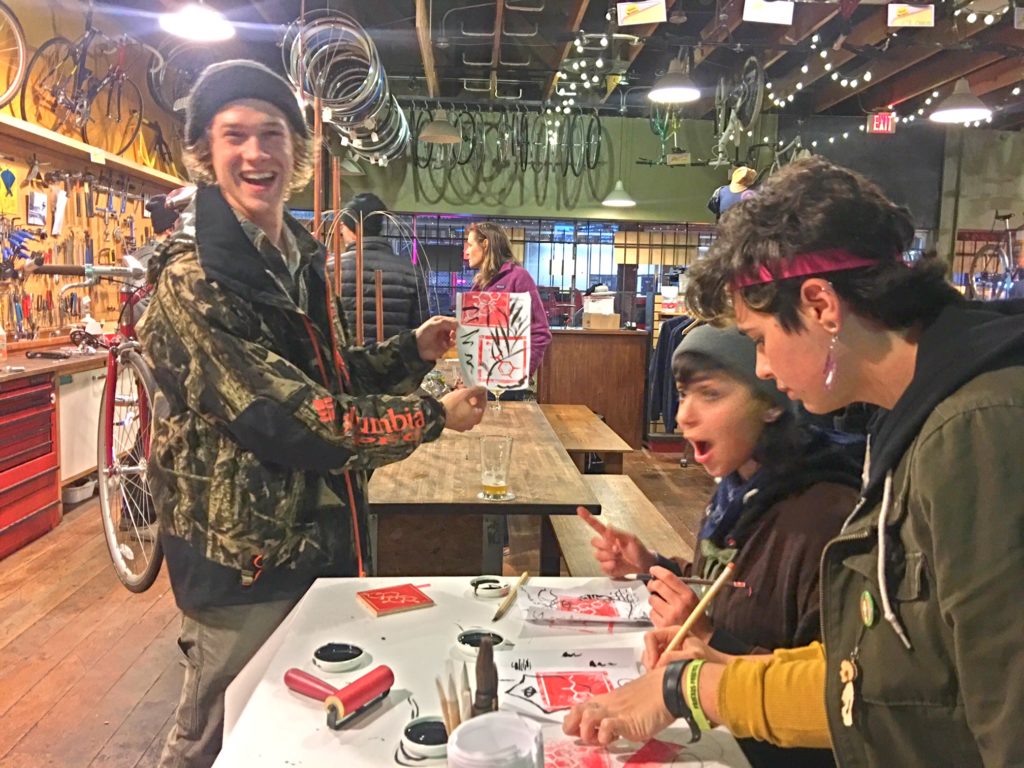

Tamasen Hayward, a graduate student in Neuroscience at WSU Vancouver, joined Kanani Miyamoto, a recent MFA graduate of the Pacific Northwest College of Art, to present a public Noggin talk at the venerable Velo Cult bike shop and pub titled “Stressed out, burned out: Strategies to stay balanced from the studio and lab…”

LEARN MORE: Kanani Miyamoto, Right Brain Initiative

LEARN MORE: Coffin Neuroscience Lab, WSU Vancouver

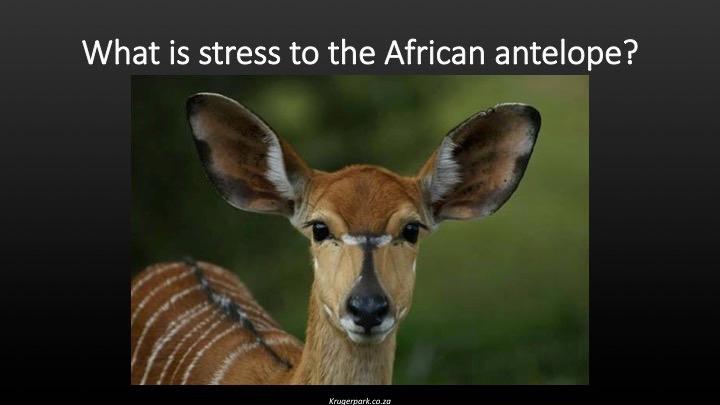

Tamasen began by defining stress, and how the experience relates to changes in the body – and also to how those changes are processed and interpreted by the brain. For example, she asked us to consider what stress might be like for an African antelope…

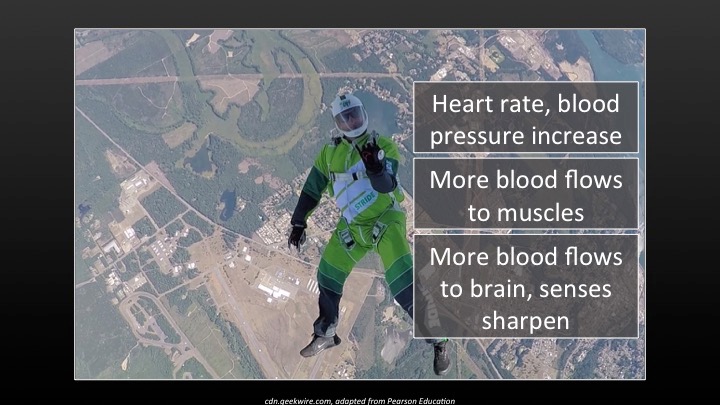

Stress is, first and foremost, an emotional response – physical changes in the body, including changes in heart rate, blood pressure, circulating hormone levels, expressions, posture. However these changes are also mapped in brain regions capable of supporting perceptions (or feelings) of emotion – the anxiety, perhaps the terror, or in some cases the excitement and exhilaration of an experience where the body is ready and prepared for action…

EXPLORE MORE: The Experience of Emotion

EXPLORE MORE: The embodiment of emotional feelings in the brain

She asked us to consider which animal in this situation is stressed, and which is the cause of that stress (the “stressor”). Is it the antelope, or the lion..?

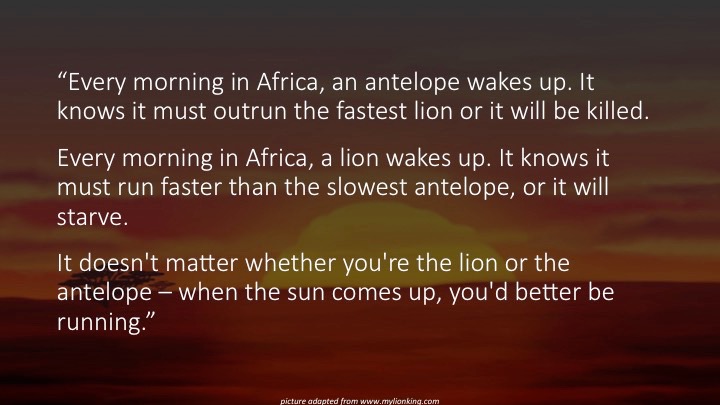

Or perhaps both? Tamasen read us a relevant quote from Christopher McDougall, an American foreign correspondent for the Associated Press who covered civil wars in Rwanda and Angola:

“Every stress leaves an indelible scar, and the organism pays for its survival after a stressful situation by becoming a little older.” -Hans Selye

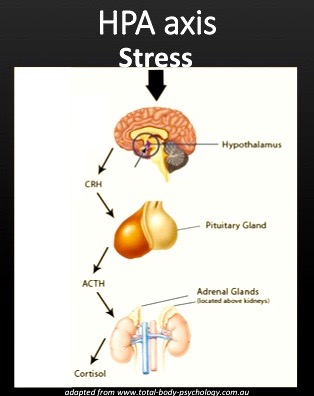

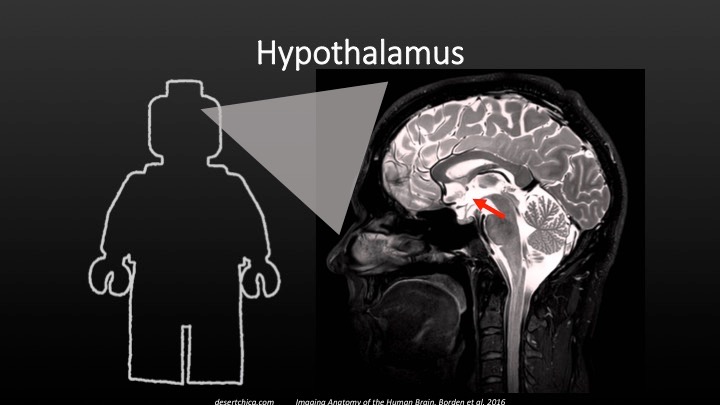

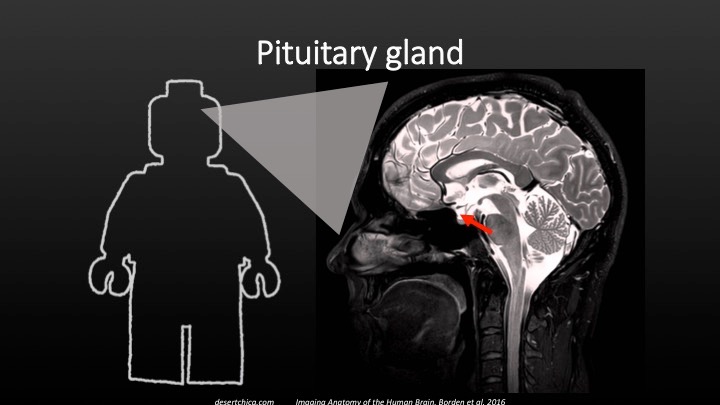

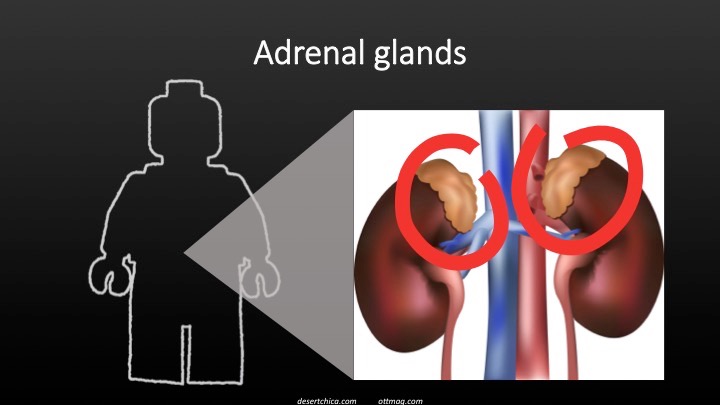

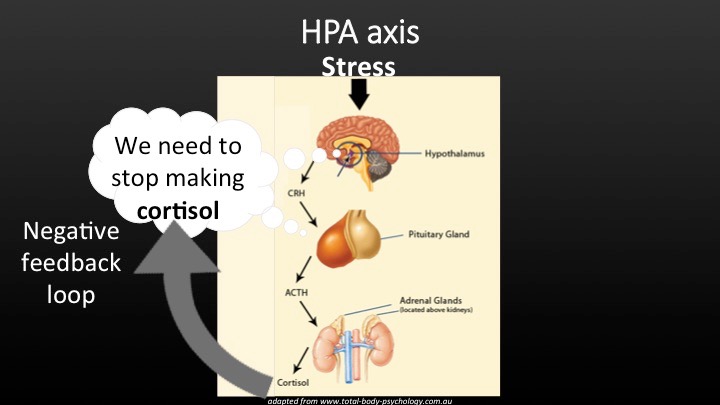

Tamasen then introduced us to a core biological component of our stress response mechanism, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (or HPA) axis. These three structures, two (hypothalamus and pituitary gland) found in the brain and one (the adrenal glands) located on top of each kidney, talk with each other through the release of chemicals, called hormones, that travel through the blood to reach and influence their targets…

The hypothalamus is critical for monitoring aspects of our body’s internal milieu, including temperature, blood pH, salt balance, glucose. It also receives inputs from other brain structures, like the almond-shaped amygdala nuclei found in our temporal lobes which respond to stimuli associated with external threats – that lion, for example, or perhaps an angry email from your boss. When stressors are detected, the hypothalamus increases sympathetic nervous system activity (so your heart rate and blood pressure increase), and informs your brain’s cortex (so you perceive (feel) drives like thirst, hunger, etc., and act accordingly). But the hypothalamus also releases an important chemical known as corticotropin releasing hormone, or CRH…

CRH travels through a well-filtered set of blood vessels to the anterior pituitary gland, where it promptly binds to CRH receptor proteins embedded in pituitary cell membranes, provoking release of another hormone known as adrenocorticotropic hormone (or ACTH). ACTH is released by the pituitary gland into general circulation, and travels to the adrenal glands atop your kidneys…

The adrenal gland cells express receptors for ACTH, and ACTH binding initiates release of cortisol, an important stress hormone, from these gland cells into the blood. Cortisol receptors are found in many tissues throughout the body, including brain, and mediate many of the body and brain responses to stress – both acute (e.g., lion here now) and chronic (e.g., ongoing trauma)…

Hans Selye, an Austrian-Canadian hormone researcher, was among the first to describe the role of the HPA axis in response to chronic stress. Selye noted that patients with various medical disorders all “looked sick,” and experienced many similar symptoms, including the development of peptic ulcers. He began experimenting with rodents, exposing them to different stressors, and discovered the same changes regardless of which noxious stimuli he introduced. He termed this consistent response to stress the General Adaptation Syndrome…

EXPLORE MORE: Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome (Selye, 1936)

EXPLORE MORE: Evaluating the Role of Hans Selye in the Modern History of Stress

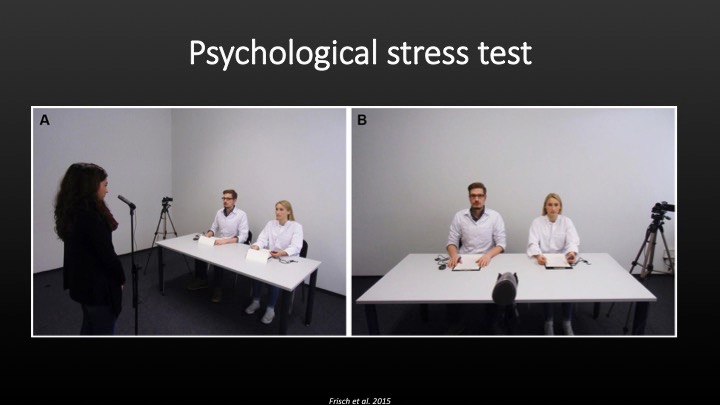

Tamasen noted that Selye was not very good with his rodent test subjects, and basically stressed them significantly no matter which tasks or stimuli his experiment involved. She then invited up a member of the audience to briefly experience one psychological task used to provoke a stress response in human research subjects, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST)…

Subjects are asked to give a speech, and solve complex math problems in the presence of a “socially evaluative audience,” while autonomic and neuroendocrine measures are monitored…

LEARN MORE: The Trier Social Stress Test protocol for inducing psychological stress

Our Velo audience, however, was pretty relaxed and nonjudgmental!

Acute stress, noted Tamasen, is often highly beneficial, improving memory and cognition, directing needed resources and arousing the brain and body to meet challenging times. That energy to get out of bed and start moving, for example, depends on increased release of cortisol in the morning…

And release of cortisol in response to acute stressors acts to inhibit further CRH and ACTH release from the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, so the stress response is often self-limiting. This is known as a negative feedback loop…

However, chronic activation of the HPA axis is another matter…

Internally generated memories of traumatic events, and excessive rumination – dwelling on unmet responsibilities or unpleasant experiences – can prolong activation of the stress response, and over time, this harms both the body and the brain…

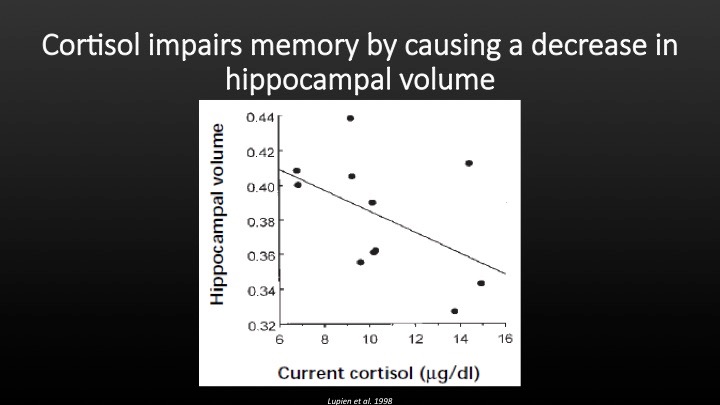

One particularly negative consequence of prolonged HPA axis activation is the cortisol-mediated death of neurons in the hippocampus, a medial temporal lobe structure essential for memory.

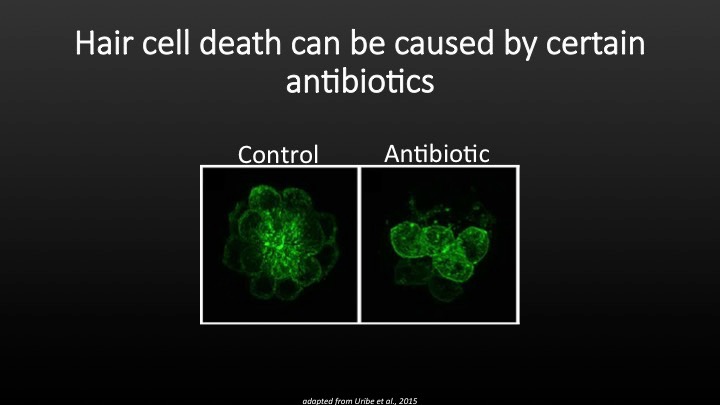

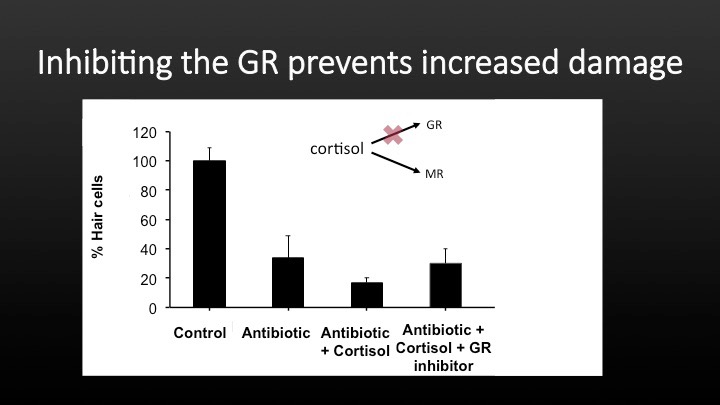

Tamasen’s own research in the Coffin Lab at WSU Vancouver examines stress effects on hair cells, which are found in our inner ears, allowing us to detect sound. Hair cells are also found along the bodies of zebra fish, where they can be studied more easily…

Some antibiotics are known to damage hair cells – damage made worse if the animal is chronically stressed. However, by blocking cortisol receptors (specifically glucocorticoid receptors, GR), the stress-mediated increase in hair cell loss can be effectively prevented…

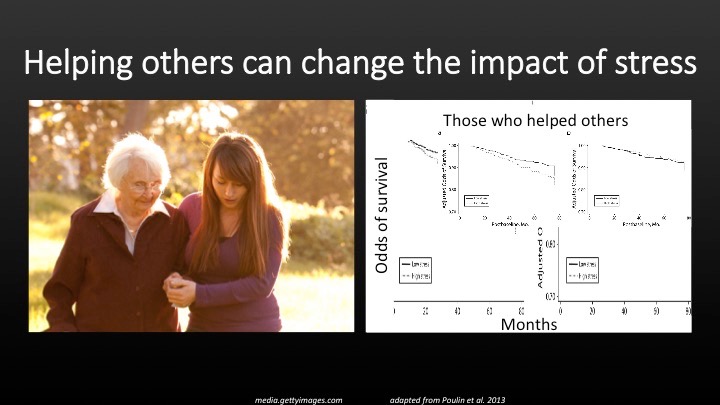

A more accessible research-supported method of reducing stress and avoiding chronic activation of the HPA axis is particularly relevant at this time of year. Helping others reduces stress! It also apparently reduces your risk of dying… 🙂

EXPLORE MORE: Giving to Others and the Association Between Stress and Mortality

EXTEND YOUR LIFE (?): SUPPORT NW NOGGIN (now a 501(c)(3)!)

Kanani Miyamoto then took the stage to introduce the tale of Bodhidharma, an Indian Buddhist monk who traveled to the famed Shaolin Temple in China to teach. He reportedly found the monks there in poor health, exhibiting signs of Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, and chose to live in a cave for 9 years, concentrating and developing meditative exercises to improve their lives.

Daruma dolls, popular in Asia, depict the intense devotion and perseverance of Bodhidharma, who Kanani told us ultimately lost his arms and legs from meditating intensively while facing a wall for almost a decade without moving! Now that sounds stressful!

However his meditative techniques can help you reduce stress. For a few minutes that night we planted both feet firmly on the wood floors of Velo Cult, closed our eyes, and focused on our own breathing – and then looked up feeling (at least this participant) a bit less stressed…

EXPLORE MORE: Meditation: In Depth (NIH)

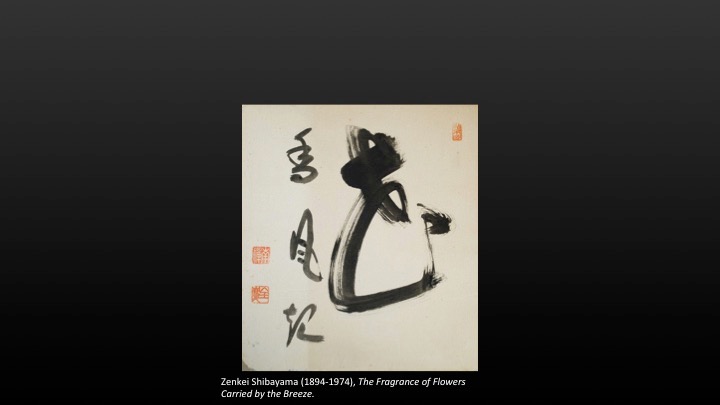

Kanani also discussed calligraphy (Shodo in Japanese, Shufa in Chinese) as a practice that involves focusing your energy and attention and emotional expression into one continuous brush stroke…

She’s found it personally helpful for stress management, and there is research evidence that supports her experiences as well…

EXPLORE MORE: Calligraphy and meditation for stress reduction: an experimental comparison

EXPLORE MORE: Cognitive-Neural Effects of Brush Writing of Chinese Characters: Cortical Excitation of Theta Rhythm

Kanani also showed us some of her own artwork, including an arresting installation at PNCA…

EXPLORE MORE: Kanani Miyamoto Print Media MFA Capstone 2016

She also created a gorgeous set of hanging scrolls, depicting the various structures and hormones intimately involved in the stress response! These hung at Velo Cult, providing a dramatic backdrop for a compelling and timely presentation on stress and the brain…

LEARN MORE: Scrolls of Stress and Balance by Kanani Miyamoto

After the talk, many folks joined us around the bike shop tables to examine some real human brains, and make their own woodblock prints, with sumi e ink, depicting cortisol, and adrenaline!

Many, many thanks to our accomplished Noggin participants, and to Velo Cult – by far our favorite stress-free bike shop and pub on planet Earth… ?

“The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.” -William James