Post by Sam Mutschler-Aldine, an undergraduate studying Psychology and Interdisciplinary Neuroscience at Portland State University.

This is not an exaggeration: I have been playing music since before I could walk.

My parents brought my sister and I over as infants to our neighbors’ house to play on their set of marimbas. We were instantly hooked. In kindergarten, my neighbor let me tag along to her elementary school marimba band rehearsals, and by third grade, we had joined two more bands. We went from our hometown of Corvallis, Oregon to Eugene once a week to play in groups there. I played marimba in middle school band classes, and while studying in high school for the SATs. I still play them today.

“If you can get people listening to the beauty of the sound of the marimba, not watching how you are technically playing, then that’s it: you’re playing music!!” — Gordon Stout

LEARN MORE: What is the Marimba?

I found it interesting that after learning such a unique style of music, it was much easier to learn new forms of music, new instruments, and even to learn in settings unrelated to music.

Practicing marimba helped me in school. Learning to remember melodies improved my memory, and somehow made concepts in math, science, and language classes easier to understand. We were aurally taught – without sheet music – which made me listen more intently during both rehearsals and in other contexts. Playing in bands even translated to skill in sports, as the collaboration, synchronicity, and creativity of music performance trained me in better teamwork.

Using music to inform my understanding of other subjects was an example of interdisciplinary study, or study across multiple disciplines. This is something I value highly now.

LEARN MORE: Long-Term Impacts of Early Musical Abilities on Academic Achievement

LEARN MORE: Influence of music on the hearing and mental health of adolescents

LEARN MORE: How musical training affects cognitive development: rhythm, reward and other modulating variables

LEARN MORE: Effects of music in exercise and sport

LEARN MORE: Music is My Copium

These experiences were the roots of my curiosity in interdisciplinary studies.

PSU has an interdisciplinary neuroscience minor, and since I had enjoyed learning about psychology throughout my OCD treatment, I figured I would try it out. The fact that it involved so many topics I was interested in and was actively studying – biology, environmental science, music, and psychology – was captivating and helped me engage with the material. I even began learning how to draw and be more creative through my neuroscience classes. As I learned more about interdisciplinary research, I was eager to find more collaborative opportunities at PSU.

LEARN MORE: Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Minor at Portland State University

Luckily, many people have worked on this same idea for years, including folks at NW Noggin. Through outreach, I talked with community members pursuing innumerable different jobs, learning more and more about how our disciplines often fit together.

LEARN MORE: What is outreach like?

We also learned that the kids we talked with were interested in the idea of interdisciplinary study, but maybe less interested in collaboration on (some) school projects. It turns out that there is a broad range of research on this subject, supporting both the benefits of classwork collaboration when it is used in certain ways and the drawbacks of using it in other ways.

For example, working in environmental science teams with peers to survey streams, I learned about fish and stream macroinvertebrates. This was helpful, because input from my classmates as we gathered data gave me unique insights and prepared me for working on teams in the jobs I have now.

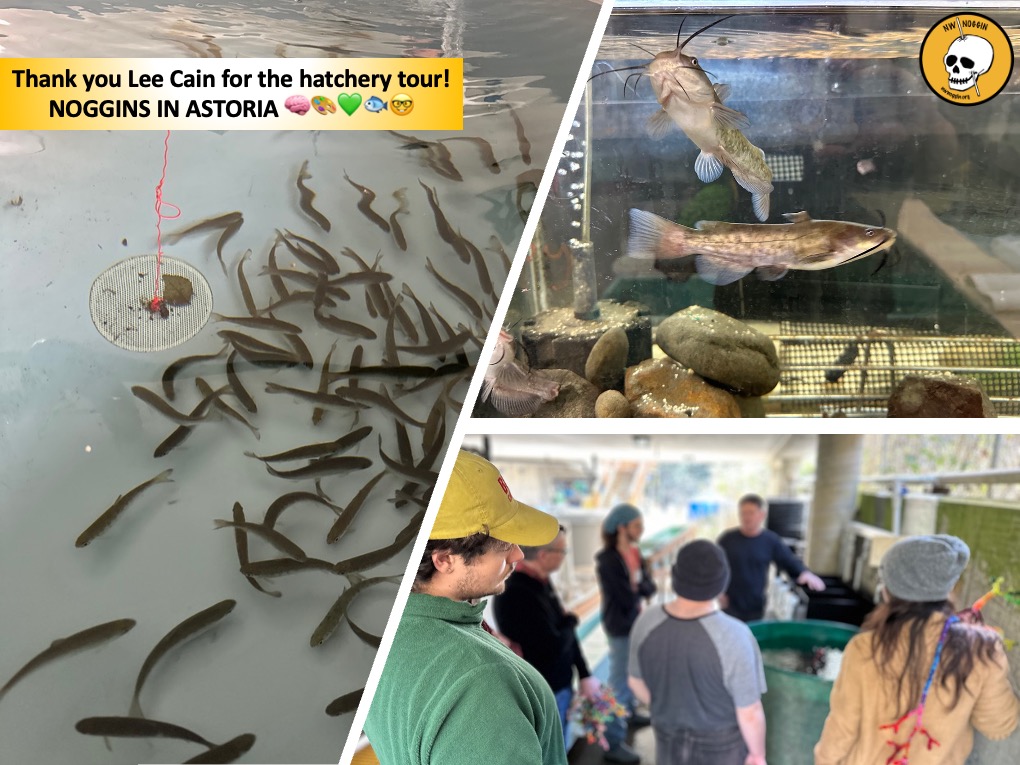

During outreach on Oregon’s North Coast we met a biology teacher at Astoria High School, who after a day of art and brains introduced us to their fisheries program.

It was exciting to hear how students loved their hands-on group learning opportunities, and I enjoyed reflecting on my own environmental science, art and neuroscience background during this tour. Just like surveying streams and marimbas did for me, I think that these experiences will apply to other areas of high school students’ lives. I found it another good example of effective interdisciplinary collaboration.

In many visits with NW Noggin I heard questions about how people work together.

Most of these burning questions on collaboration regarded team sports like soccer, or how people become in sync playing video games. Two students from Astoria High School asked me how our brain recognizes people – another wonderful question which turns out to be related to how we collaborate!

The Neuroscience of Collaboration

So, how do our brains allow us to collaborate with other people?

LEARN MORE: Electroencephalography (EEG)

Our brains produce various coordinated electrical rhythms, or brain waves. One of these rhythms is called the Phi complex. These Phi brain waves have recently been linked to collaboration between brains!

There are two kinds of Phi rhythms in the brain, called Phi1 and Phi2. Phi1 rhythms have been found to be associated with independent behavior while Phi2 are associated with cooperation!

LEARN MORE: The phi complex as a neuromarker of human social coordination

Collaboration between brains: Getting in synch

Amazing studies have been conducted using the system pictured above. Electroencephalograms (EEGs) are recorded simultaneously from two people in a technique called hyperscanning. One study looked at brain activity when people were told they were collaborating with a human versus when they were told they were collaborating with a computer (in reality they were collaborating with a human in both cases). When comparing EEGs between partnered subjects, the study found “integration between the two subjects’ brain activity in the Joint condition, and to a segregation in the PC and Solo conditions.”

In other words, when people believed they were collaborating with another human, their brain activity was in sync with their partner, but when they believed they were collaborating with a computer, their brain activity was not in sync at all!

LEARN MORE: Investigating the neural basis of cooperative joint action. An EEG hyperscanning study

LEARN MORE: Brain Interaction during Cooperation

LEARN MORE: Investigating Cooperative Behavior in Ecological Settings

LEARN MORE: Phi: A voyage from the brain to the soul.

Another study found a possible mechanism for synchronization between brains.

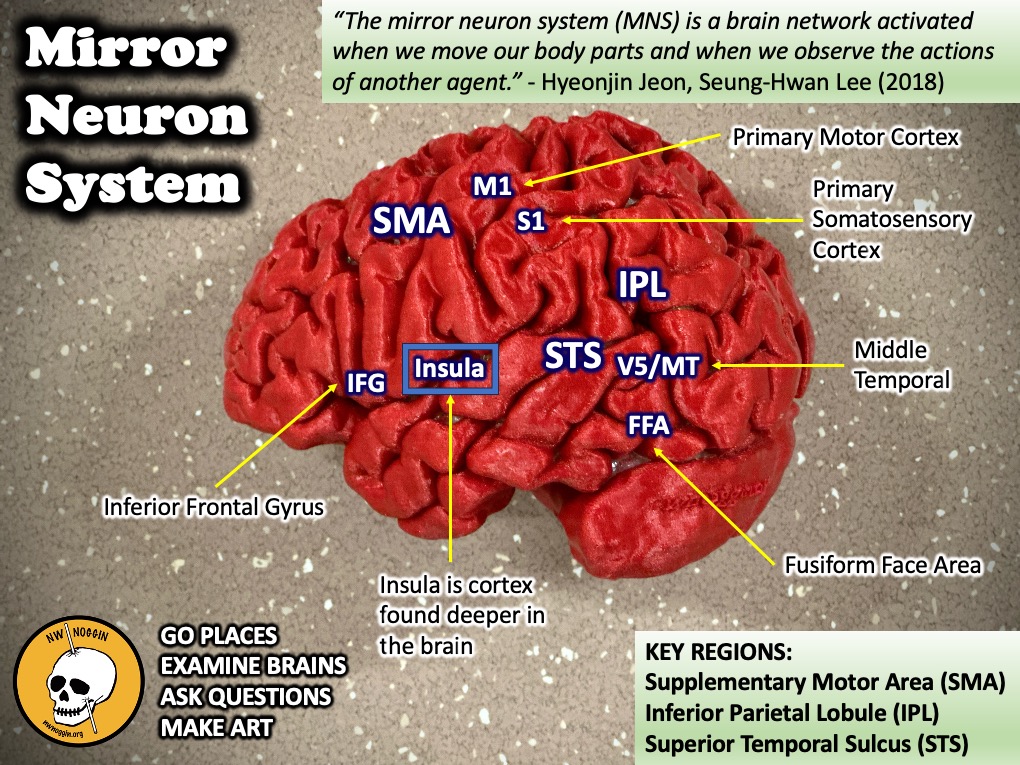

The concept is called IBS – and no, not that IBS. In this case IBS stands for Inter-Brain Synchrony. This term describes exactly what students have been asking about during outreach: how are humans able to get “in sync” with each other. This study suggested that we may utilize what are called “mirror neurons” during collaboration, perceiving success or failure and over time and developing a feedback system. The authors explain that “this network‐specific feedback system could potentially allow for synchrony of brain and motor activities between cooperating human agents while performing a cooperative task as one of multiple elements within an intra‐interpersonal gestalt of top‐down processing.”

This mirror neuron system is what could allow synchronized swimmers to perform extremely coordinated choreography, players of team-based video games to make successful plays, and classmates to work well together. It is amazing nonverbal communication between brains!

LEARN MORE: A New Collaborative in Neuroscience

LEARN MORE: Inter-brain synchrony in teams predicts collective performance

LEARN MORE: Inter-brain synchronization occurs without physical co-presence during cooperative online gaming

Collaboration within brains

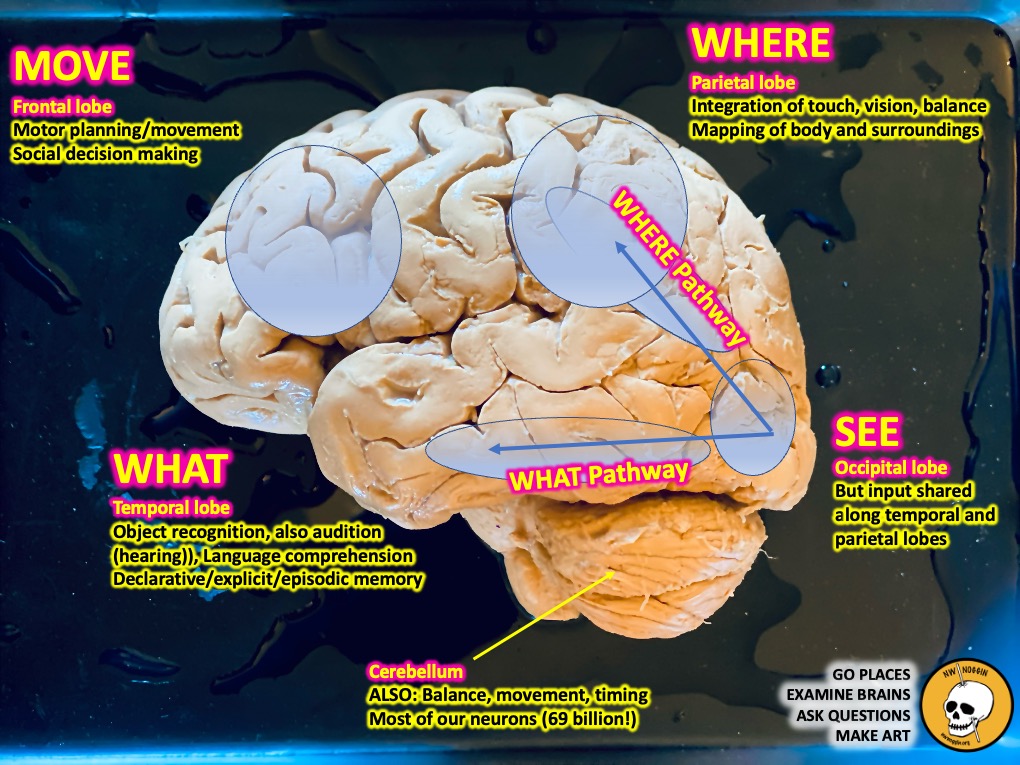

Collaboration does not only occur between brains – it also occurs within each of our individual brains, every second! For example, in soccer, when a defender sees the ball about to reach their net, multiple brain areas are communicating to understand what and where the ball is while they race to block it.

This diagram represents the way our brain visually processes what and where things are.

After light bounces off an object and enters our eyes, signals are sent via the thalamus to the primary visual cortex (or V1). From V1, information is shared along two cortical pathways for further processing. The pathway that helps us identify the object is called the “ventral stream,” as it involves areas in the more ventrally located temporal lobe. It’s also called the “What Pathway.” The pathway that helps us understand where the object is in space is called the “dorsal stream,” as it involves more dorsal areas of the temporal and parietal lobes.

Using these two pathways, we can understand that we are looking at a soccer ball, and that this ball is hurtling towards the goal. This system is one reason why a defender may be able to reach this ball before someone else and save it.

LEARN MORE: Central Visual Pathways

LEARN MORE: Insights from the Evolving Model of Two Cortical Visual Pathways

Building an interdisciplinary whole

All this dense information can seem very daunting!

“The basic thesis of gestalt theory might be formulated thus: there are contexts in which what is happening in the whole cannot be deduced from the characteristics of the separate pieces…” — Max Wertheimer

The theory of gestalt can be summed up by a quote from Kurt Koffka: “It has been said: The whole is more than the sum of its parts. It is more correct to say that the whole is something else than the sum of its parts, because summing is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part relationship is meaningful.”

Interestingly, our brains combine many different inputs to understand what we are seeing or sensing. So, our brains are constantly combining small parts to form a greater whole!

LEARN MORE: A Century of Gestalt Psychology in Visual Perception

LEARN MORE: The Irreducibility of Vision: Gestalt, Crowding and the Fundamentals of Vision

LEARN MORE: Resting-state neural correlates of visual Gestalt experience

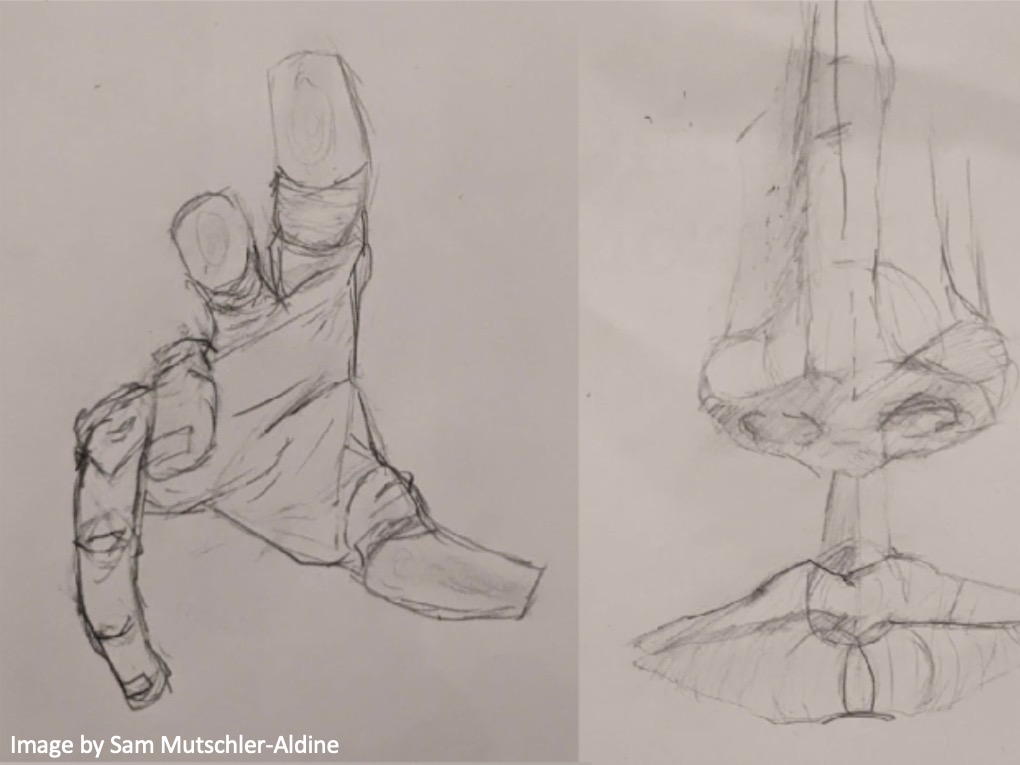

The way our brains categorize objects is by recognizing patterns of texture, shape, shading, color and size. This is why it can be hard to recognize an object when a picture is too far zoomed in, but once you see the normal sized picture you can understand what you are looking at. Again, the whole has meaning while the parts may not. And by not explicitly understanding what object you’re examining, you see the lines and patterns and can draw what you see – and not the object you assume is there.

TRY THIS: Grid Drawing Task

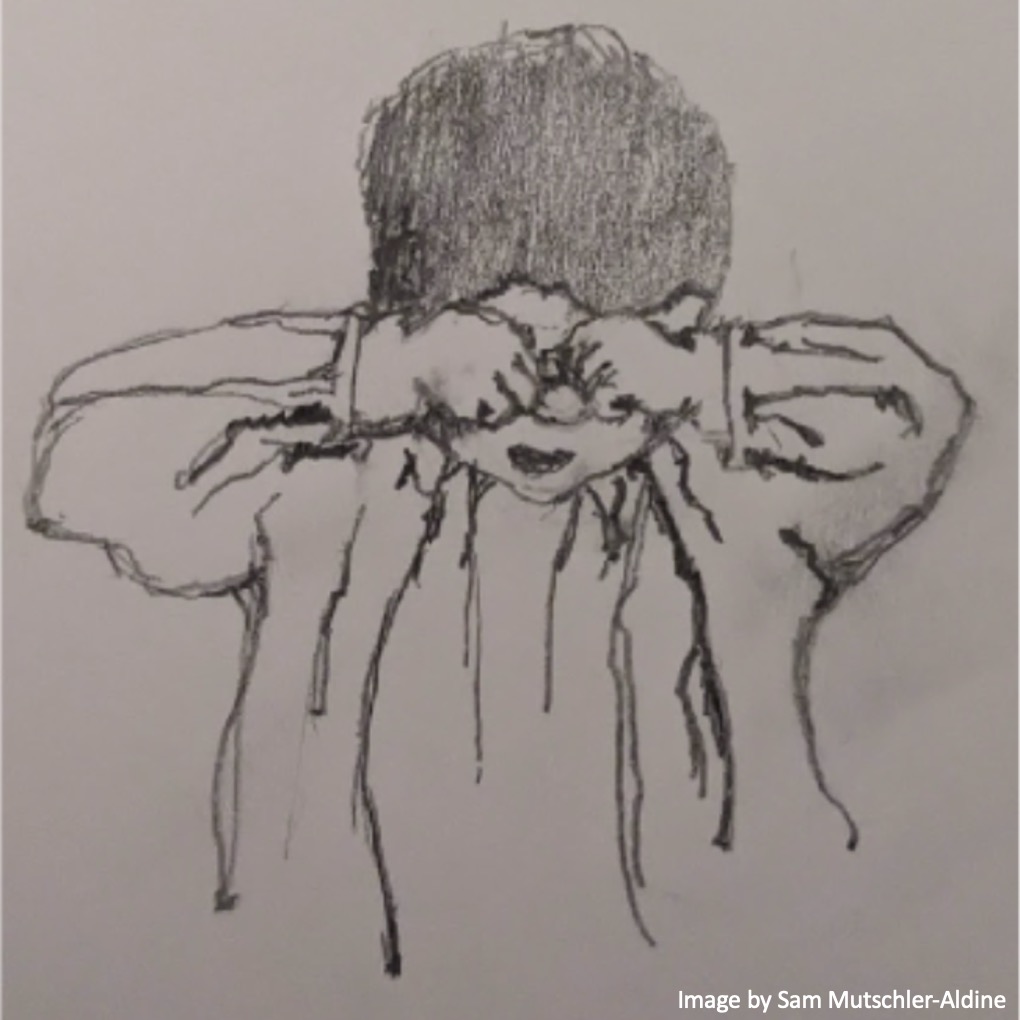

This was the assignment that made me realize I actually could draw, using gestalt principles from my interdisciplinary Perception class. Once the pieces are put together, it should be clearer what this is.

I began to copy other people’s art using the same technique the class had used – I broke up each image into squares in my head and used landmarks to replicate them.

My efforts in interdisciplinary programs at PSU grew from my childhood experiences of mixing disciplines, while finding amazing, reciprocal opportunities to flourish in different environments. Art and music played a major formative role in my ability to learn and perform well in the fields I study, while psychology classes have similarly informed my practice of both music and art.

I enjoy looking at art through the lens of neuroscience and vice versa – each have the capability to be empirical and creative. Going forward, I plan to draw on my experience with the marimba and other arts to inform my practice of psychology, and to draw on psychology research to inform the way I pursue my music and art. Collaboration is always key.