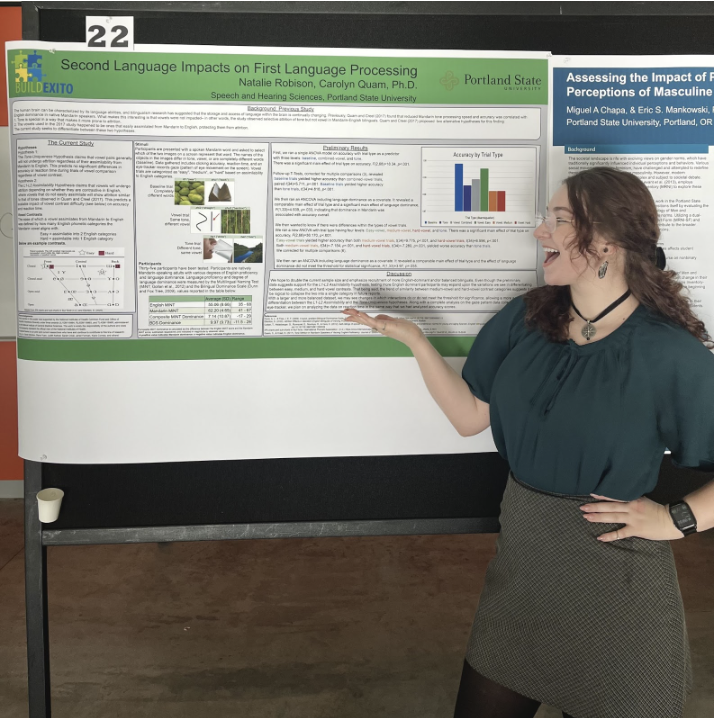

Post by Natalie Robison, Portland State University alumna, Northwest Noggin outreach participant and current research assistant at the University of Washington.

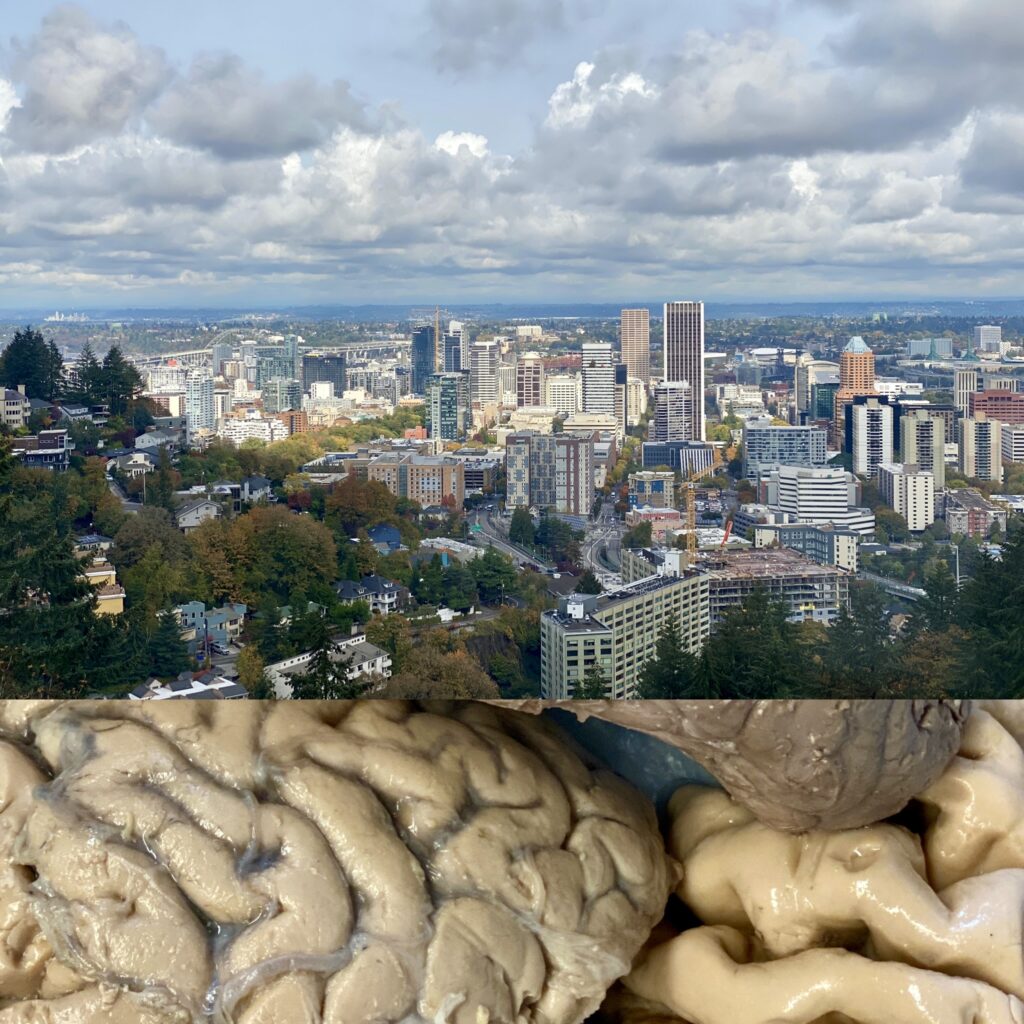

When I was in the sixth grade my class took a field trip to downtown Portland to ride the tram that connected the hilltop and riverside buildings of Oregon Health & Science University.

This was one of the first times I visited my state’s largest city, and even though the view was new to me, I was more interested in the medical science that the tram supported by quickly transporting doctors and scientists between facilities. The rural town where my classmates and I grew up, Canby, didn’t have an urgent care center until 2007, and it will be many years before a hospital is built.

In fact, Canby is considered a Medically Underserved Area, according to the Health Resources & Services Administration of the United States.

LEARN MORE: Is your county considered medically underserved?

LEARN MORE: What Is Shortage Designation?

My sixth grade teacher, Ms. Kimberly Kent, has a natural resourcefulness when it comes to teaching science and fostering academic passions in rural schools. I, of course, later went on to volunteer with NW Noggin, bringing preserved brains and hands-on activities to classrooms in poor, rural, and underserved communities– just like the kind I grew up in.

Then, I realized, we could actually visit the classroom I grew up in!

LEARN MORE: Noggin in Canby Schools!

This was a special visit because I got to reflect with my old teacher on my later educational difficulties, such as not being diagnosed as neurodivergent until my later teen years, and how educators can fill gaps like the ones I slipped through.

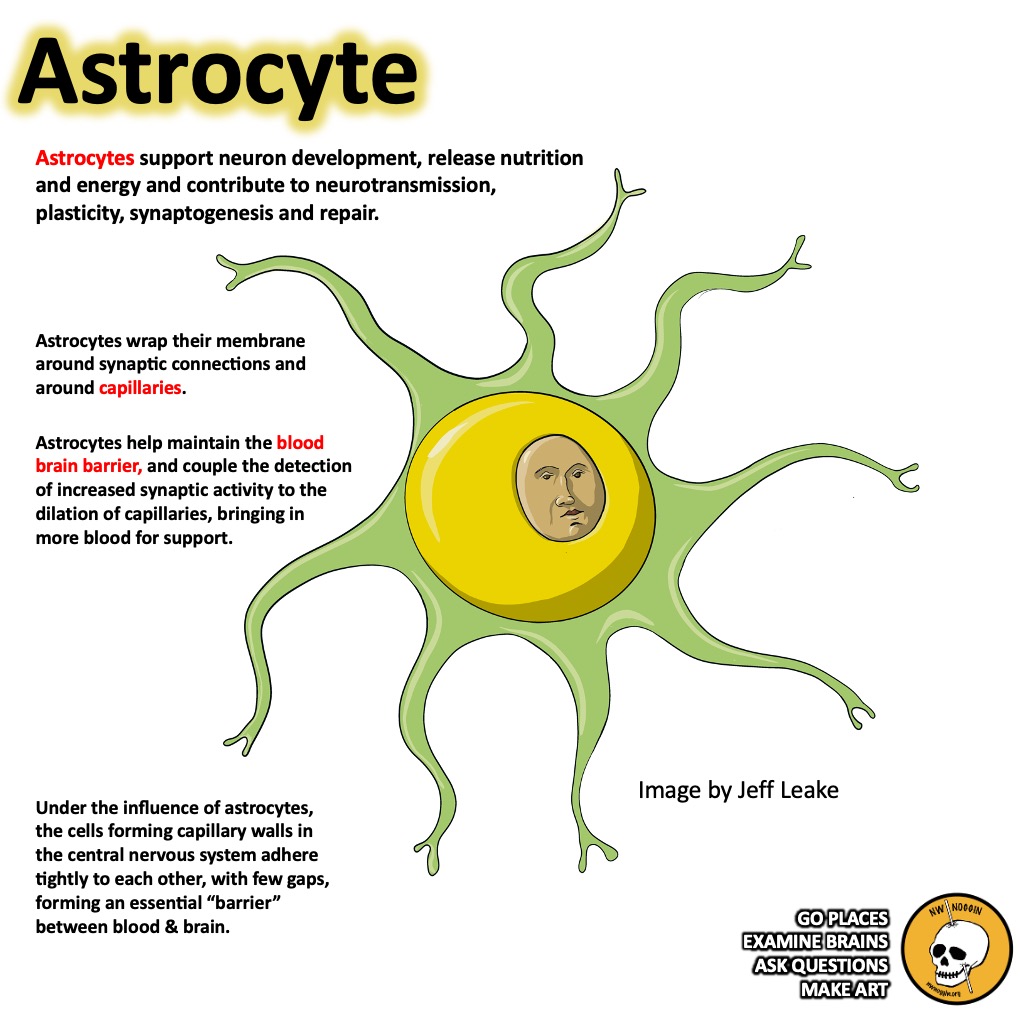

You may recognize my name from my other Noggin post, A Brain without Glia, where I reflected on the independent nature of my pursuit of neuroscience. In that post I suggested that formalized neuroscience education and educators were like glial cells, the cells that support neurons.

I felt like my university, Portland State, was and is capable of doing much more to platform and institutionalize the field of neuroscience that is more than simply “biology + psychology.” It was only after I’d learned enough on my own that I could think critically about my own experiences and identify those crucial gaps.

LEARN MORE: A Brain without Glia

LEARN MORE: Neurodiversity

LEARN MORE: Resilience in the face of neurodivergence

When visiting classrooms with NW Noggin, it feels like I’ve become one of those glial support cells, in a small way. My own school and teachers guided me, so when I returned there with NW Noggin to share neuroscience and guide others, I termed it “retrograde” signaling to characterize this full-circle moment. Keep reading to learn more about the reflections made by my sixth grade teacher and me, including the impacts of legislation and topics like neurodivergence in the classroom.

LEARN MORE: A Brain Without Glia: Navigating Neuroscience Without Structural Support

LEARN MORE: Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Minor @ Portland State University

“High functioning,” but by what standard?

Ms. Kent was my sixth grade teacher, which in Canby is still part of elementary school, where students have the same teacher for the majority of classes/subjects year-round. In elementary school, I was identified as a “Talented and Gifted” student (TAG), an Oregon Department of Education classification which meant that I was academically inclined and needed to be challenged more.

LEARN MORE: Oregon’s Talented and Gifted program

My school didn’t have the right resources to meet my academic needs, but Ms. Kent kept me challenged by having me tutor my peers in math and science. I remember feeling that spark inside when I could feel my friend’s stress melt away when solving for X finally clicked in her mind. Unfortunately, I only had one year with Ms. Kent, and the worst of my educational struggles were yet to come. Before I get there, I want to discuss the relationship between neuro/intellectual diversity and how legislatures define academic success.

Is this logo familiar to you?

Is it because you grew up in no-child-left-behind-era Oregon, where you had to do yearly “state testing” called OAKS?

US schools during this era (2002-2015) were the subject of an educational “experiment” called the No Child Left Behind Act, where a school’s funding was based on how well their students performed on annual state tests. This included punitive measures against teachers that performed below (what tended to be exceedingly high) standards. The idea was that schools and teachers would be motivated to make sure every child in their classrooms could do well, rather than just focusing on the “easy” students who could get good grades with relatively less support. The problem, of course, is that this is based on a faulty assumption. Educators are already motivated to help every student, including those who struggle most, that’s why they are teachers. The thing that stands in their way is low education budgets, which reduce the teachers’ ability to individualize students’ education plans to meet their unique needs. Also, consider that schools’ budgets largely derive from property taxes: this is a class issue which this policy only perpetuated. Many other writers and journalists have covered this issue with more skill and depth than I, so please read their work linked below if you want to learn more.

LEARN MORE: Overview of the No Child Left Behind Act in Oregon

(each state set their own standards and regulations under the Act)

LEARN MORE: The statistics behind why teacher performances do not account for the variation in student performances

LEARN MORE: Side effects of large-scale assessments in education

LEARN MORE: ⅓ of school budgets come from local property taxes

The annual tests tended to prioritize reading, writing, and math– subjects linked to being a productive worker– and less on music, art, and history.

This represents a conflict between what the legislation expected from its investment in education (economic productivity) and what education was originally meant for (developing kids into well-rounded individuals). Ushering students into this narrow range of skills, while neglecting other skills, harms all students regardless of their skill set. Those who struggle with reading/writing/math get the message that, because they’re not strong in the skills schools had to prioritize, then they’re not strong in anything, which of course is not true. And for those like me who happened to be good at those subjects, it was assumed I was good in everything, which was also not true. I needed to develop my interpersonal, introspective, social/emotional processing skills, but because schools couldn’t make room for those skills, and because I was “high functioning” (able to mask well), and because my grades were good, there were no “red flags” for the school to pick up on. In reality, they were just working with a list of red flags that was too short.

LEARN MORE: Women/AFAB individuals are more likely to have inattentive-type ADHD & are more likely to be diagnosed later: “Miss. Diagnosis: A Systematic Review of ADHD in Adult Women”

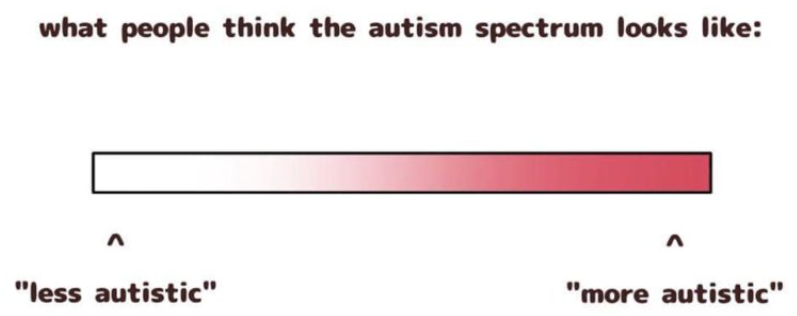

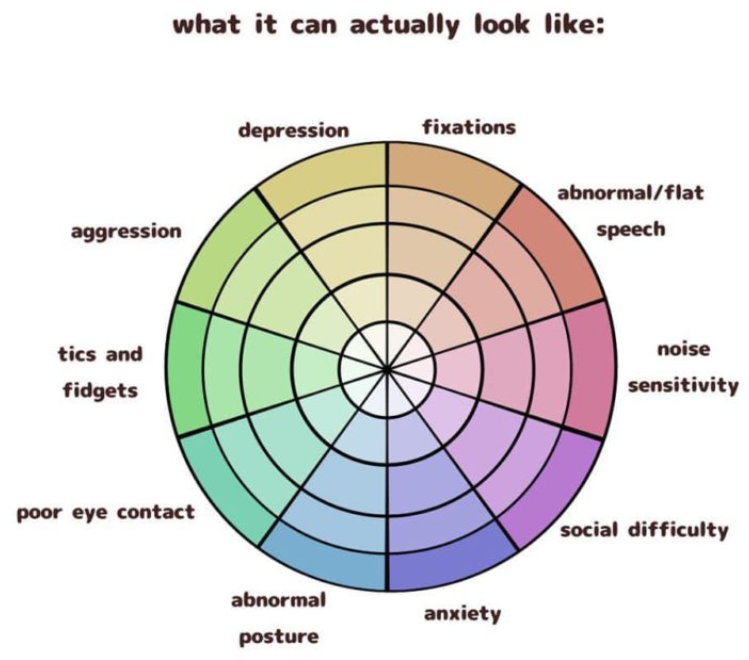

This dynamic is analogous to the different ways Autism presents in different individuals. Nera Birch’s article on The Mighty describes this wonderfully– so please give it a read– but I’ll be referring to the graphics which explain my point well.

IMAGE SOURCE: Tumblr user levianta, as cited by Nera Birch

LEARN MORE: This Graphic Shows What the Autism Spectrum Really Looks Like

Autism is not the linear spectrum that it was classically described as. Instead, different individuals on the spectrum can experience unique combinations of symptoms. With my particular flavor of Autism, I tend to struggle socially but have strengths in STEM subjects. Someone I knew in high school had the opposite combination: they excelled socially, but struggled academically. It’s no surprise that they were diagnosed with Autism much, much earlier than I was.

You might be wondering what’s the harm in ushering students to fit a certain standard, even if the standard is just related to job success. Well, as someone who by chance happened to fit the mold, the skills I didn’t develop ended up being vital to my wellness in later years. In corporate terms: The “economically unimportant” skills would have kept me able to pursue the “economically important” skills.

Let’s circle back to the conflict between what the legislature expects from schools and what the original intention of schooling was (and for educators like Ms. Kent, still is). Legislation like No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) effectively assign teachers a deeper role in students’ lives. Students may be left behind because they need counseling, or food security, or different social services, which schools recognize and provide accordingly. It’s good that schools do this, but teachers are punished for it. On one side it’s considered government overreach, and cuts to social services and education are called for. On the other side, cutting some support for education and social work is considered a valid compromise, to appeal to as many voters as possible, when there’s no evidence to validate cuts in the first place. There wasn’t evidence to support the worst parts of NCLB and ESSA, as forewarned by educators, but it still received bipartisan support.

Is it political to say we need to get politics of all kinds out of education?

LEARN MORE: Top-down control of education standards: The Oregon legislature has repeatedly made changes to teaching, testing, and graduation requirements (sometimes, later reversing those changes). When kids go through grade levels with changing requirements over the years, consistent educational outcomes are less possible.

LEARN MORE: Bottom-up control of education standards: Washington Post explains reforms that can improve the ESSA by giving power from federal/state/local politicians to the educators

LEARN MORE: What issues in public K-12 education are at the forefront of Oregon’s state legislation as we enter 2025? Article by OPB

How neuroscience informed my education

As a middle and high school student, I was in a weird position. I really struggled socially, emotionally, and at home, but I still earned good grades– and grades are the metric that are usually used to identify if a student needs support. I was under the impression (along with those around me) that I was experiencing regular “teenage girl” issues, like friendship drama and hating waking up early– maybe, at most, some depression and/or anxiety. I was actually experiencing Autistic burnout and had predominantly inattentive ADHD (though I wouldn’t know this until my diagnosis at age 19), and I also struggled with a much lesser-known form of bullying that is more likely to impact girls and those who are neurodivergent. Lacking this insight, I instead thought my issues were with brain chemistry. In middle school I began a decade-long cycle of being prescribed antidepressants, experiencing negative side effects, increasing the dosage and “pushing through,” only to conclude that a different medicine or combination thereof is better to try.

DID YOU KNOW? Autistic burnout is a relatively new concept, and is commonly misdiagnosed as depression, anxiety, and other disorders.

LEARN MORE: Gender differences in bullying: Non-physical aggression is more difficult to identify and address

LEARN MORE: Autistic individuals are more likely to be victimized by their own friends and peers

DID YOU KNOW? Similarly to its rankings in public education, Oregon ranks among the worst states for mental healthcare

Learning that I have ADHD and am on the Autism spectrum was, unsurprisingly, deeply consequential to all aspects of my life. I was in community college at the time, and educationally I began to understand how things like sensory overload impact my ability to function in classrooms. I got disability accommodations, such as for noise-canceling headphones, and I felt comfortable in classrooms again. This was when I got the confidence to define my educational goals, and I realized that I found the most joy when learning about how my brain works. I decided to study cognitive neuroscience, and I never stopped asking how I could use what I learn to my own advantage.

The value of neuro-outreach

As a tutor, I love sharing study tips and working with students to find out which methods work the best for them. As a neuroscience lover, I love learning how motivation works, how memory encoding works, and how mental processes work uniquely for those with ADHD, OCD, Autism, depression, and more. Meeting the unique needs associated with neurodiversity and disability increases one’s ability to work toward their goals; this requires understanding both the brain and oneself. For example, I learned that part of my ADHD causes my brain to prefer some kinds of tasks over others, at different times of the day. I’d heard that you can break down large tasks into smaller ones, but that never worked for me. Instead, I began working on tasks based on my current energy levels rather than by deadline. It sounds counterintuitive, but I haven’t missed a deadline since.

I feel like so much of my personal growth has been a matter of understanding how I work differently than others, like a big puzzle that has consequences on your life’s path. I also feel extremely lucky to be able to pursue neuroscience, developing academic tools that can also be directed inwards for my own growth. It’d almost feel selfish to not share what I’ve learned and help others learn how to understand themselves better. This is why I have loved doing outreach with NW Noggin so much. Meeting with K-12 students who need neuroscience education the most, seeing the gears turn inside their head and connecting the brain to their own experiences– that’s exactly what kept me interested in science as I grew up.

The Retrograde Signal: Visiting Canby with NW Noggin

I reached out to Ms. Kent in the spring to set up a fall visit to her classroom. It’s always fun to catch up with those who had formative roles in your life, and this is especially true when you’ve had a complex relationship with education. We reflected on how my educational pathway unfolded after I left her classroom, and how the challenges I faced were invisible to me for so long. There were gaps in the safety nets of my K-12 education and I slipped through them. What can be done to fill those gaps?

According to Ms. Kent, one important step we can take is to re-evaluate how we treat the teaching profession. Teaching K-12 is relatively low-paying, and teachers often buy their own art supplies, work long hours at home after school, and take second jobs to supplement their income. And if that wasn’t enough, recall how teachers are expected to, and are consequently punished for, identifying the extracurricular needs that may be holding a student back. These economic and political barriers make it increasingly more difficult for teachers to do what they signed up to do: support a child’s academic and social/emotional development.

LEARN MORE: More teachers are getting second jobs- on top of already working 50+ hours per week!

LEARN MORE: Even back in 2015, many teachers cannot afford to live where they teach

Within the classroom, one solution is to embrace individual differences. It sounds obvious, but let me give an example. The table groups in math classes used to be organized by skill level (in my experience), with the assumption that students who are around the same skill levels will be able to help each other better than groups of students with mixed skill levels. Ms. Kent knew that I needed to be challenged when she let me spend class time tutoring my peers, and in doing so I used my strength to improve my weakness. I was good at math and liked puzzles, but I needed extra support to develop my emotional intelligence, introspection, and communication skills. I didn’t realize that at the time, but Ms. Kent did, and she knew that my need to be challenged included such interpersonal skills. And, it turns out research supports peer-peer support in the classroom: Seating students in “mixed proficiency groups” is much better for student learning outcomes (of all levels) than when separating groups by skill level.

Another solution is to more explicitly recognize and support neurodiversity in the classroom – more than the current standards do, based on grades and standardized performance. The thing about neurodiversity is that the symptoms aren’t the result of some brand-new brain function that neurotypical individuals don’t have. Rather, the neurodivergent brain prioritizes some things over others, in ways a neurotypical brain might not. Massive sensory stimulation, for example, may disproportionately impact neurodivergent students, but they still impact neurotypical students (and students who pass as neurotypical via masking). Being mindful of accessibility isn’t just beneficial to those with identified needs, but also to every student regardless of diagnosis.

A rising tide lifts all boats – and this tide is made of cerebrospinal fluid.

Going forward: Who does knowledge serve?

Maybe you noticed the “(2002-2015)” following my mention of the No Child Left Behind Act. If it ended in 2015, then it shouldn’t be an issue still, right? Well, as Ms. Kent explained to me, not exactly.

No Child Left Behind was replaced in 2015 by the Every Student Succeeds Act. It was only an improvement in some marginal ways; it included music and art in the definition of a well-rounded education, but it didn’t do away with high-stakes testing entirely. It also (still) forced schools to compete against each other for grants, again resulting in inequality amongst schools.

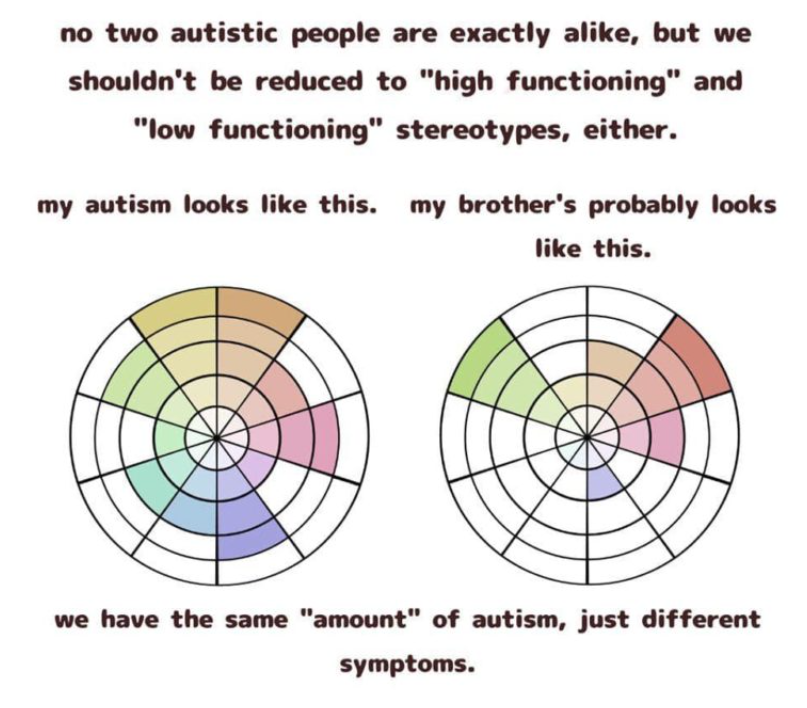

IMAGE SOURCE: Temple University Institute on Disabilities, “Health Equity”

LEARN MORE: A short description of the Every Student Succeeds Act (NPR)

People have criticized acts like No Child Left Behind and Every Student Succeeds by pointing out that it attempts to enforce equity as a result but without the crucial step of recognizing the underlying reasons why students have unequal educational outcomes in the first place. If you don’t understand the issue, then you cannot solve it. Our understanding of complex issues like educational inequity is continually evolving (like with our understanding of neurodiversity) and adapting to changing situations (like the COVID pandemic). Maybe the problem is that the decisions which structure education tend to be made by people who are not educators. They may be informed by educators, but the more removed from the classroom one gets the more likely it is that the decisions will be influenced by things like “worker productivity” and “returns on investment in education”. I won’t pretend that one group has the answers, but I will point out that the people who are most likely to have them are… the ones who have dedicated their lives to being educators. A more democratic decision-making process, where educators with a common goal of guiding childhood development are allowed more of a say in how their schools operate, is a great, evidence-based place to start. ESSA granted more authority to states and local politics rather than the federal government, which was still not a good solution because educators were left out.

If we want to address the issues in education, educators are the ones with the answers.

This applies to higher education as well. In my article A Brain Without Glia, I discussed the Huron Report, the third-party evaluation sought by PSU to identify the cause of their decline in enrollment and revenue. One of Huron’s recommendations was to reduce “administrative bloat” and instead fund academic programs more. Instead, during this time, PSU continued to cut funding to, and sometimes the entirety of, academic programs and student support. The educators – the glial support cells – consistently spoke up against these cuts. Now, PSU announced plans to lay off nearly 100 faculty members, citing budget concerns and a struggle to reach profitability.

LEARN MORE: The Huron Report

LEARN MORE: AAUP, one of the unions representing PSU teachers, response to the Huron Report

LEARN MORE: PSU Program Review and Reduction

LEARN MORE: PSU announces layoffs of nearly 100 faculty members

Were educators involved in this decision? Well, they have been involved in opposing it. Economist Howard Bunsis from Western Michigan University provided a highly detailed analysis on why PSU’s budget is actually considered healthy and able to sustain its diverse academic offerings. One major finding is that PSU labels programs like retirement funds as being paid for by the school, when really they are paid for by the state, making it seem like there is a larger gap between spending and revenue than there actually is.

AAUP has criticized the administration’s decisions to move forward with the layoffs in light of these facts, noting the possible connection between the administration’s push for more construction projects and the board members’ downtown real estate portfolios.

LEARN MORE: Economist Howard Bunsis explains the numbers behind PSU’s budget over the years

LEARN MORE: AAUP’s October 14th 2024 overview of the layoffs and “budget crisis”

PSU’s motto, Let Knowledge Serve The City, emphasizes the value – both economic and cultural – that higher education brings to Portland. These decisions which structure the university have clearly not been made by the educators. Portland State University desperately needs to let knowledge serve itself before it tries to serve the city.

If you want to speak up, please consider signing this letter to send an email to President Ann Cudd and Trustees asking them to stop the cuts. You could also email the Portland real estate developer Sheryl Manning, who… is also on the PSU Board of Trustees as the Finance and Administration chair: sheryl.manning@gmail.com. To stay up to date on this developing situation, the AAUP website posts regular updates, along with student journalists at PSU Vanguard (Instagram: @PSUVanguard).

Fallor ergo sum

“I err, therefore I am” – Saint Augustine

To be human is to make mistakes. That is how we learn, after all.