Post by Hannah Hauser, an undergraduate pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Liberal Studies and an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

Exploring neuroscience and learning more about how our brains and bodies work will forever be fascinating… I frequently find myself saying “How did I not know this before!?”

Starting in preschool and elementary school, many of us are taught about our famous five senses and how they are essential in interacting with the world. We learn these as “sight”, “sound”, “smell”, “taste”, and “touch”, and they are pretty commonly known. However, what if I told you that there are more than five senses… a few that aren’t as widely known and might be considered your invisible senses?

There are many additional senses – and researchers have proposed several as a sixth. However, I would like to introduce, what I call your invisible sixth sense: proprioception!

LEARN MORE: The Body’s “Sixth Sense”

LEARN MORE: The search for a sixth sense: the cases for vestibular, muscle, and temperature senses

LEARN MORE: Rethinking the senses and their interactions: the case for sensory pluralism

Before I entered college and began my journey in neuroscience I had never heard of proprioception, and I thought maybe I was the only one who had never encountered this concept so I decided to ask around. After talking with friends, family and college graduates, almost all of them said they had never heard of it either. A few claimed to recognize the word, but didn’t know what it meant. I saw this as a great opportunity to dive into what proprioception and your proprioceptive system actually are!

What IS proprioception? How is proprioception experienced in our everyday lives?

Proprioception means “perception of yourself.” We need to know where our body is.

The word derives from the Greek proprius, which means “our own,” as in our own property. Proprioception is our ability to sense our body’s position in space, including movements, actions and locations of our limbs in relation to ourselves and where other objects are.

We use proprioception everyday, in something as small as grabbing a cup of water to drink, or tying shoelaces, writing, walking, running, driving or carrying boxes. We execute these fine and gross motor movements with ease and efficiency, often not even thinking much about our conscious position!

LEARN MORE: Proprioception

LEARN MORE: The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force

LEARN MORE: Flex Your Muscles … and Your Brain!

Here’s one classic and quick way to test your proprioceptive abilities:

If you successfully touched each of your fingers to your nose with your eyes closed, your proprioceptive system is doing its job!

Where and how does proprioception function in my body and brain?

Let’s start with the big picture… among the various lobes in our brain, the parietal lobe is most critical for making sense of a lot of somatosensory information that is relayed from our bodies. The parietal lobe is responsible for the integration of touch, pressure, vibration, position, and the somatosensory spatial mapping of our self and surroundings, as well as vision and vestibular information.

LEARN MORE: Neuropsychology of the parietal lobe

LEARN MORE: Proprioceptive alignment of visual and somatosensory maps in parietal cortex

LEARN MORE: Topographic maps of visual spatial attention in human parietal cortex

LEARN MORE: Multisensory maps in parietal cortex

If we take a closer look, within our parietal lobe and just behind the central sulcus (a “valley” of cortex centrally located in the brain) we find primary somatosensory cortex (S1), which is also known as the postcentral (“after” the central sulcus) gyrus. This area is specifically in charge of mapping touch, proprioception, and additional tactile sensations from the body.

LEARN MORE: Neural Basis of Touch and Proprioception in Primate Cortex

LEARN MORE: Proprioceptive activity in primate primary somatosensory cortex during active arm reaching movements

LEARN MORE: Multimodal interactions between proprioceptive and cutaneous signals in primary somatosensory cortex

In the body itself we find specialized sensory neurons known as mechanoreceptors, including a specific class known as proprioceptors. Mechanoreceptors are a type of somatosensory receptor that are highly sensitive to external stimuli/mechanical manipulation, everything from deep pressure to something as light and minute as a bug crawling across your leg.

Deep within your muscles and tendons, sensory receptors (or “afferent” receptors) called proprioceptors provide detailed information on your body’s movement, position, and muscle tension. They can be activated movement, as in a stretch!

Two important types of proprioceptors are muscle spindle fibers and Golgi tendon organs. Muscle spindle fibers are twisted around specialized muscle fibers and are very sensitive to whether muscles are being stretched or lengthened. These afferents send crucial, continuous, and detailed feedback to the spinal cord and brainstem. Golgi tendon organs are seated in our tendons and inform the central nervous system of muscle tension and how much we are exerting.

Sensitivity to muscle tension is crucial for avoiding injuries caused by too much force or overexertion. Muscle spindle fibers and Golgi tendon organs detect and regulate varying aspects of flexibility in our muscles, joints, and tendons, and work together to communicate essential sensory information related to proprioception!

LEARN MORE: Flex Your Muscles … and Your Brain!

LEARN MORE: Mechanotransduction in the muscle spindle

LEARN MORE: Muscle spindle function in healthy and diseased muscle

LEARN MORE: Human muscle spindles are wired to function as controllable signal-processing devices

LEARN MORE: The Golgi tendon organ: a review and update

LEARN MORE: Other Afferent Feedback that Affects Motor Performance

LEARN MORE: New functions for the proprioceptive system in skeletal biology

How do these messages get from the body to the brain?

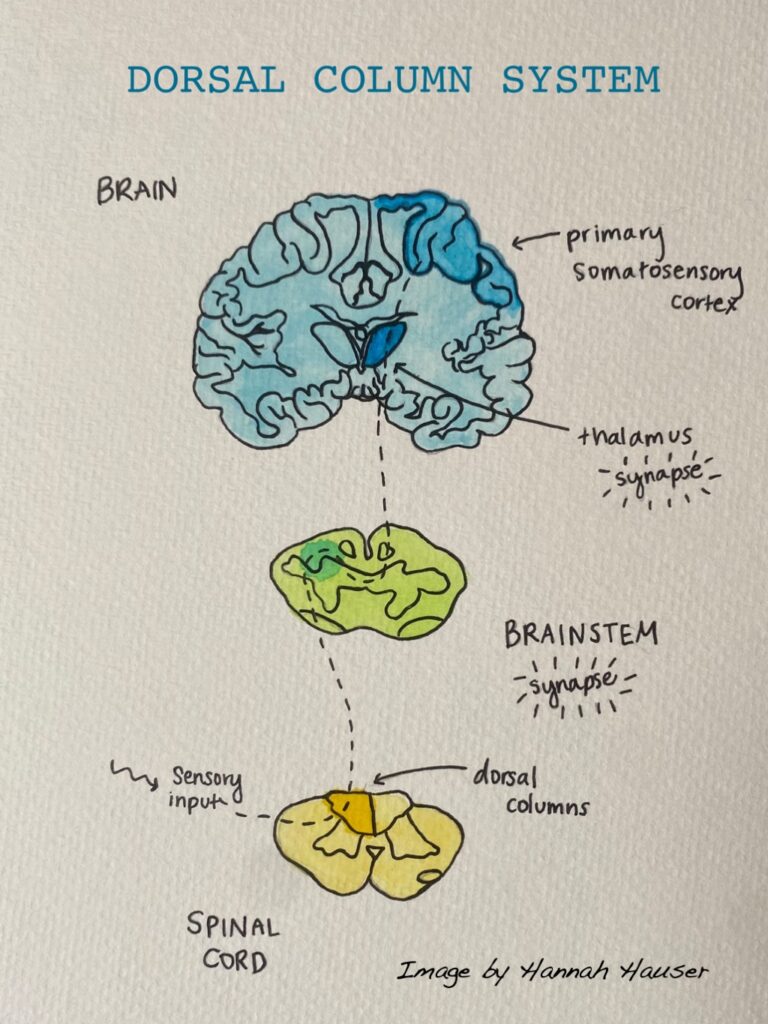

Signals from our proprioceptors (and other mechanoreceptors) ascend along the dorsal column pathway, rising up the dorsal (back) columns of the spinal cord, and then synapse at the brainstem. At the brainstem the signal crosses over to the thalamus for further processing, and continues to ascend to ultimately arrive at the primary somatosensory cortex (or S1) in the parietal lobe.

NOTE: To create the drawing above I was inspired by a diagram in neuroscientist Guy Leschziner’s book The Man Who Tasted Words. (If you are interested in the neuroscience of sleep, check out his book The Nocturnal Brain: Nightmares, Neuroscience, and the Secret World of Sleep!)

LEARN MORE: ‘The Man Who Tasted Words’ forces readers to question their reality

LEARN MORE: Science in The Spotlight: The Man Who Tasted Words

LEARN MORE: Muscle Spindle and Golgi Tendon

LEARN MORE: Mechanoreceptors Specialized for Proprioception

LEARN MORE: Functional Neuroanatomy of Proprioception

What if I lose my proprioception?

Proprioception is so integral to our everyday functioning and lives, it can be very hard to imagine what it would be like to lack this automatic ability. However there are some people who do have an absence of spatial awareness, which can drastically impact their mobility and chance for recovery.

IMAGE SOURCE: What is Proprioception? Understanding the “Body Awareness” Sense

Ian Waterman is an example of an individual who lost his sense of proprioception as a result of a rare autoimmune disease that attacked proprioceptors in his body from his neck down. These neurons no longer relayed sensory information to his brain, so he could not feel his body and effectively command it to function. Waterman is an example of one who was miraculously able to adapt to this neurological loss by depending on the body’s other senses (such as vision!), and is currently able to coordinate his movements to walk, stand and use all of his limbs quite efficiently.

Take a look at this brief, casual interview with Ian Waterman and Jonathan Cole!

Still curious about Ian Waterman’s story? Watch “The Man Who Lost His Body” documentary linked below or look into reading Losing Touch: A Man Without His Body by Johnathan Cole!

LEARN MORE: Proprioception

LEARN MORE: Losing Touch: A man without his body

In the book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, neurologist Oliver Sacks describes, in the chapter “The Disembodied Lady,” a woman named Christina who was affected by sensory neuritis (a.k.a sensory neuropathy), resulting in a loss of proprioception.

Christina was left with awkward flailing movements, limbs wandering without conscious intent, difficulty standing and sitting up and, as with Ian Waterman, her hands would wildly overshoot or miss if she tried to feed herself or grab something. With a lot of time and effort in rehabilitation and therapy, Christina also made a recovery by learning to adapt to the loss with the help of her remaining senses.

“She had, at first, to monitor herself by vision, looking carefully at each part of her body as it moved, using almost painful conscientiousness and care… the normal, unconscious feedback of proprioception was being replaced by an equally unconscious feedback of vision…”

— Oliver Sacks

Curious to look more into Christina’s story? Read “The Disembodied Lady” at the link!

READ HERE: “The Disembodied Lady” The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Still curious? Read Rahel’s experience with her loss and journey in recovery of proprioception in Guy Leschziner’s chapter in The Man Who Tasted Words titled “The Stuff of Superheroes!”

How can I improve my proprioception?

I want to become an occupational therapist.

Occupational therapists (or OTs) and Certified Occupational Therapy Assistant (COTAs) work together to support patients using therapeutic techniques to improve and rehabilitate everyday skills we need to gain independence in day-to-day living. Some individuals need assistance with their fine motor skills for writing and fastening buttons, or help with sensory processing difficulties. Occupational therapy can help us all understand how the brain functions and see and support the diversity in all of us.

LEARN MORE: What is Occupational Therapy?

LEARN MORE: Why Would Someone Need Occupational Therapy?

LEARN MORE: COTA education and professional development

Occupational therapists can support their patients with proprioceptive function!

There are many therapeutic activities and resources online for babies, toddlers, and children to assist in meeting developmental milestones and reinforcing skills, as well as effective exercises for older children and adults. For those who are “sensory seeking” and require additional proprioceptive input, there are many strategies large and small to help them with everyday activities.

LEARN MORE: Classroom Sensory Strategies for Proprioceptive Input

LEARN MORE: Occupational Therapy Sensory Seeking for Helping Children

LEARN MORE: Assessing proprioception: A critical review of methods

IMAGE SOURCE: “The Power of Active and Passive Proprioceptive Input”

Knowing where your body is can benefit your movement and mental health, and exercising your proprioceptive skills can help you thrive. Here are some healthy activities that can be completed by almost anyone of any age in your day to day life:

Alongside our “sixth sense” of proprioception, there are vast, fascinating systems in our brains and bodies that regulate and let us keep up with our favorite activities. These remarkable biological systems work together to make what we experience natural and effortless. With curiosity and exploration, we can teach and learn from each about how we interact with the world around us.

Thank you Northwest Noggin, and all my fellow outreach volunteers, for providing such exciting opportunities to foster and support curiosity, growth, and community connections for us all!