Post by Rocio Garcia, an undergraduate in Psychology pursuing a minor in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience at Portland State University. Rocio is currently a substitute teacher at the Montessori of Alameda school in Portland, Oregon.

My name is Rocio Garcia, and I am an undergraduate senior at PSU, majoring in Psychology and minoring in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience. I am also a substitute teacher at Montessori of Alameda, a private, tuition charging school, where I currently teach little preschoolers.

A Montessori school offers an educational environment based on the philosophy of Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator who believed that every child is a unique individual who should explore what motivates them. The program prioritizes children’s natural interests and activities more than some conventional teaching methods. Montessori emphasizes direct learning and real-world skills, as well as independence, and views children as naturally eager for knowledge and capable of initiating their own learning in a sufficiently supportive and also well-prepared learning environment.

LEARN MORE: Montessori education: a review of the evidence base

LEARN MORE: The Behavioral Effects of Montessori Pedagogy on Children’s Psychological Development and School Learning

LEARN MORE: Beyond executive functions, creativity skills benefit academic outcomes: Insights from Montessori education

Because of my own teaching experience at Alameda, I became curious about why preschoolers act aggressively or angrily in certain situations without using language to communicate or describe what they need or want.

I was interested in researching this topic because I often see a lot of behavioral issues in my classrooms, including hitting and biting. Therefore, I would like to find effective ways to support my students when they are having challenging times inside and outside the classroom.

In fact, outreach this term has allowed me to gain more knowledge about how the brain plays a significant role in the development of stress responses and how stress can negatively affect both children’s and adults’ bodies, behaviors, and minds. “How does stress affect our brain?” was a question I heard during my visits to Portland Public Schools, so I decided to research this topic based on the behaviors seen daily in my classroom with young preschool students.

What behaviors do I see in my school?

Scenario #1: Outdoor play time

Playing outside is a fun form of recreation that my students enjoy, as they get to learn physical skills while playing outdoors and create strong social bonds as they interact. However, some children will make awful or inappropriate choices, such as hitting and biting, to get toys they want from each other, without using language to verbally communicate what they need or want.

IMAGE SOURCE: Montessori of Alameda

LEARN MORE: The importance of outdoor play for young children’s healthy development

LEARN MORE: Aggression During Early Years — Infancy and Preschool

Scenario #2: Inside the classroom

During indoor time when children get to do activities either individually or cooperatively with other friends, yelling and screaming are some of behaviors I often see in the classroom. When I try to redirect their behavior or bring their attention back towards what we are learning or doing, many children tend to scream at me or at other friends (e.g., “Go away!” or “I need space”). They are clearly upset and frustrated, but unable to express their feelings effectively.

IMAGE SOURCE: Montessori of Alameda

LEARN MORE: Montessori education: a review of the evidence base

At some time during each day almost all the kids will (at least occasionally) have tantrums, or act aggressively, angrily or defiantly.

Why do some preschoolers act this way?

In order to understand why young children struggle to use their words during stressful situations, it’s crucial to start with a basic knowledge of how our brains react to stress and perceived danger.

The stress response begins in the brain.

When we face a stressful situation, our brain activates its survival mechanisms. This complex response system includes what is known as the “fight or flight” response, enabling us to react acutely (quickly!) to perceived threats driven by our sympathetic nervous system.

LEARN MORE: The sympathetic nervous system in development and disease

LEARN MORE: Asymmetric effects of acute stress on cost and benefit learning

LEARN MORE: Correlation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity during rest and acute stress tasks

When we perceive or confront an oncoming external danger, a brain region called the amygdala, found deep in our temporal lobes, is capable of initiating a stress response.

For example, when we react to an aggressive animal, our eyes and ears transmit that information to our amygdala, which can set off powerful changes in our bodies and brains.

LEARN MORE: Stress-Induced Functional Alterations in Amygdala: Implications for Neuropsychiatric Diseases

LEARN MORE: Amygdala Activity, Fear, and Anxiety: Modulation by Stress

LEARN MORE: Neural responses to acute stress predict chronic stress perception in daily life

LEARN MORE: Perceived stress modulates the activity between the amygdala and the cortex

When danger is detected, the amygdala immediately notifies another brain region, the hypothalamus, of a potential threat. The hypothalamus sends a hormone (CRH) to the pituitary gland, which then relays a message to the adrenal glands (found above the kidneys), also via a hormone (ACTH). Our adrenal glands release additional stress hormones including cortisol and adrenaline into the bloodstream.

LEARN MORE: Evaluation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function in Childhood and Adolescence

LEARN MORE: Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response

LEARN MORE: The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress

When the pituitary gland releases ACTH, it also activates the Sympathomedullary Pathway (SAM), which eventually triggers more acute, short term responses through that sympathetic nervous system, which increases our heart rate and breathing rate, makes us sweat, decreases digestion, increases muscle tension and more!

LEARN MORE: Sympathoneural and Adrenomedullary Responses to Mental Stress

LEARN MORE: Altered Pituitary Gland Structure and Function in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

LEARN MORE: Functional organization of autonomic neural pathways

Stress is a normal biological response to a potentially challenging or dangerous situation.

In fact, there is good stress, known as eustress, that helps us effectively respond to sudden threats and handle the challenges that we encounter in our daily lives. However, if our stress continues, and does not fade away, it can lead to what’s known as chronic stress, and a child experiencing chronic stress may develop significant health problems that can affect their physical and psychological well-being.

Therefore, it is important to include stress management techniques in our children’s lives, including mindfulness exercises, physical activity, and relaxation methods, to maintain a healthy, optimal lifestyle and improve the overall quality of our children’s and own lives as well (i.e., less biting!).

LEARN MORE: The impact of stress on body function: A review

LEARN MORE: The Impact of Stress on Health in Childhood and Adolescence in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic

LEARN MORE: Stress and Learning in Pupils: Neuroscience Evidence and its Relevance for Teachers

LEARN MORE: How to Relax in Stressful Situations: A Smart Stress Reduction System

LEARN MORE: Stress Management

Secondly, young children are driven by their emotions when they are frustrated or stressed in a situation because their brains tend to be dominated by their limbic system. This of course can also happen with adults, particularly when we are significantly stressed, tired or burned out ourselves.

Layered over the brainstem we have the limbic system (sometimes referred as the emotional brain) consisting of several interconnected structures involved in emotional reactions, motivation, memory formation, behavior regulation and other important physiological functions.

The amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus and cingulate gyrus (all part of the limbic system) and the basal ganglia (another set of brain structures involved in emotional expression) are some key regions highly involved in our response to stress.

Let’s explore each of these brain structures in more detail!

AMYGDALA

The amygdala is a small, almond shaped structure involved in processing stimuli and memories associated with emotional intensity, including fear and pleasure. For instance, when you encounter a stressful situation (e.g., fighting over the same toy in the classroom), the amygdala responds by directing the body to either fight the threat (e.g., through yelling or physical aggression), flee the situation (e.g., by running away or withdrawal), or freeze up (e.g. by shutting down emotionally).

LEARN MORE: Without my amygdala, would I get scared?

LEARN MORE: Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala

LEARN MORE: Stress, memory and the amygdala

HIPPOCAMPUS

The hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped structure located in each temporal lobe of the brain, which is responsible for forming, storing and retrieving memories, spatial navigation, and emotional responses, including those related to memory and stress. Chronic stress can affect memories that are initially formed with support from the hippocampus and then ultimately stored in the cerebral cortex.

LEARN MORE: Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review

LEARN MORE: Neurocognitive effects of stress: a metaparadigm perspective

HYPOTHALAMUS

The hypothalamus is a small deep structure in the brain primarily involved in maintaining a stable internal state of the body, including responses to stress. Therefore, when the amygdala detects stress, it activates the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus then sends signals to the pituitary, facilitating the release of adrenaline into the bloodstream from the adrenal glands. However, after the stressor fades away, the hypothalamus typically suppresses this activity and the body returns to a calmer, more stable state.

In kids, an overactive hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis can lead to chronic stress, affecting their behavior and overall well-being. When the amygdala and HPA axis are dysregulated, this can contribute to behavioral issues in children including excessive anxiety, panic attacks, impulsive behavior, anger and aggression.

LEARN MORE: Stress and the HPA Axis

LEARN MORE: Stress, the brain, and trauma spectrum disorders

LEARN MORE: Nuclei-specific hypothalamus networks predict a dimensional marker of stress in humans

CINGULATE GYRUS

The cingulate gyrus is located on the medial aspect of each cerebral hemisphere, and plays a major role in regulating emotional responses and stress related behaviors. This part of the brain is also involved in controlling our autonomic motor function and behaviors. Hence, damage to this particular region can cause improper emotional responses, impaired sense of pain and learning impairments.

LEARN MORE: The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for emotion, action, and memory

LEARN MORE: The Tenacious Brain: How the Anterior Mid-Cingulate Contributes to Achieving Goals

LEARN MORE: The Anterior Cingulate Gyrus and Social Cognition: Tracking the Motivation of Others

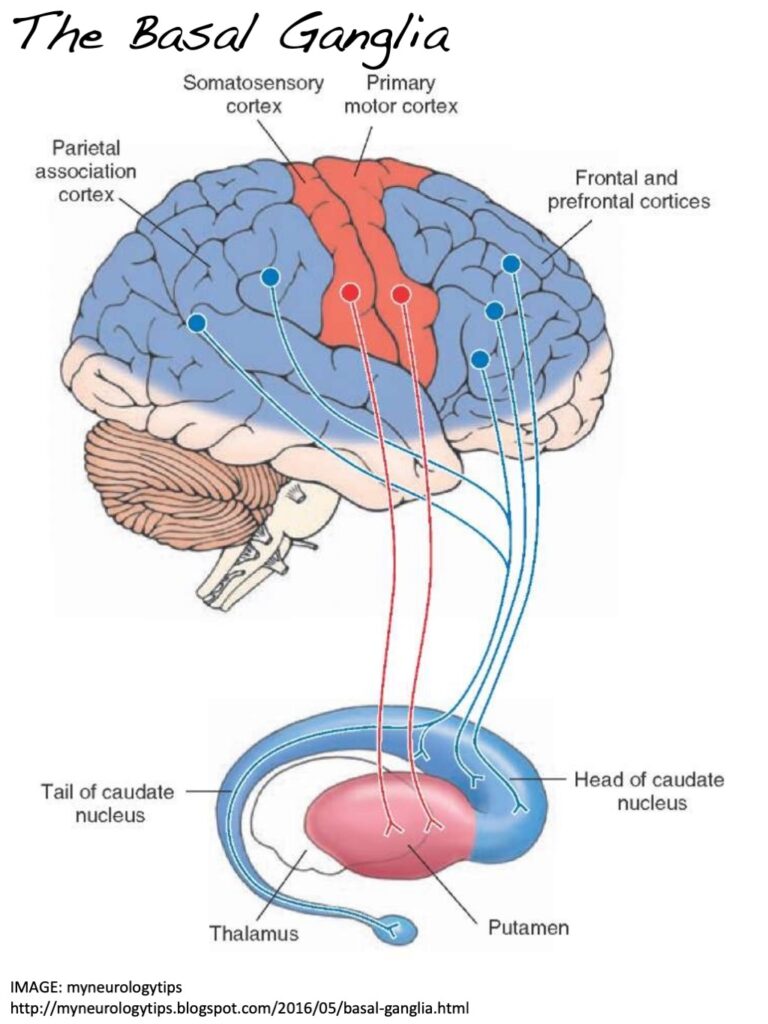

BASAL GANGLIA

Although the basal ganglia are not traditionally considered part of the limbic system, they are closely connected to limbic structures. They contribute to motor control, reward processing and habit formation. The basal ganglia are also important for the rate of movements (and the rate or speed of thoughts!) and when you do something and when you stop. So, if a person is continuously stressed, that stress can impact their basal ganglia function, affecting both their movements, thoughts and behavior.

IMAGE SOURCE: myneurologytips

LEARN MORE: Learning through mistakes!

LEARN MORE: Functions and dysfunctions of the basal ganglia in humans

LEARN MORE: Recent advances in understanding the role of the basal ganglia

LEARN MORE: Basal ganglia for beginners: the basic concepts you need to know and their role in movement control

BRAINSTEM

The brainstem and limbic system work closely together. The brainstem’s survival processes are triggered when the amygdala detects a threat in the surroundings. When these brain regions come into contact with a threat, they work together to trigger flight, flight, and freeze reactions and survival functions without necessarily assessing the type or specific details of the threat.

A critically important feature of the limbic system is that this part of the brain does not have immediate access to words and language. However, some of the responses I hear in the classroom (e.g., “Go away!”) are more stereotyped, impulsive utterances – and are more an emotional expression than a consciously considered, thoughtful, verbal response.

When activated by a significant perceived threat, the limbic system acts too quickly to communicate effectively with the parts of the brain responsible for language, or considered thought. That is why preschoolers often use physical aggression to express what they are feeling instead of speech.

LEARN MORE: Wired for behaviors: from development to function of innate limbic system circuitry

LEARN MORE: Limbic Neuromodulation

LEARN MORE: Stress Adaptation and the Brainstem with Focus on Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone

PREFRONTAL CORTEX

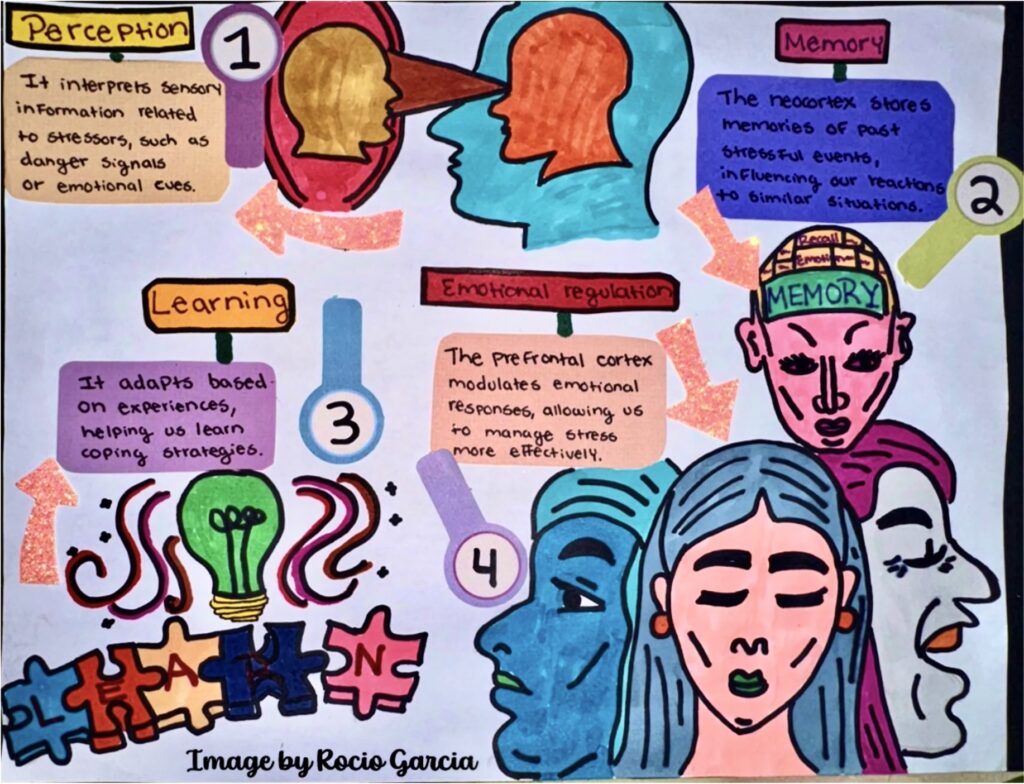

Lastly, a fascinating part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex (or PFC) is also involved in the stress responses of young children.

Prefrontal cortex is neocortex, which consists of six distinct layers of gray matter (neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, axon terminals and synapses) that surround deeper white matter (myelinated axons) in the frontal lobe of your cerebrum. It is responsible for many higher-order functions in the brain including conscious perception, voluntary movement, language, reasoning and abstract thinking.

How does the pre-frontal cortex play a significant role in understanding children’s behavior?

The PFC is like a conductor of the brain’s orchestra, coordinating stress responses, memory, and emotional regulation. Since the neocortex is not fully mature until a person is in their twenties…kids need consistent adult intervention and guidance to be able to fully access and develop this important social decision-making part of their brain.

The PFC is involved in stress responses influencing children’s behavior in a number of ways.

LEARN MORE: Recent advances in understanding neocortical development

How does stress affect a child’s PFC?

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) helps us regulate our emotions, make decisions and plan actions. This region of the brain is so vital because it’s connected with the amygdala through several neural networks that play a role in inhibiting amygdala activity, managing stress and calming down the body.

Children’s reaction to stress is greatly influenced by the prefrontal cortex. Let me clarify why.

Emotional regulation: The PFC serves as the control center for our ideas and behaviors. It functions to help us predict the potential outcomes of our actions, and exert control over our emotional responses to stress, protecting us from experiencing excessive stress. This ability to predict social outcomes and regulate emotions requires experience, and is therefore less developed in younger children.

Fear and Anxiety: The brain uses two distinct routes (the “low road” and the “high road”) to interpret and process information when it perceives a threat or stressor. One of them (the low) involves more subcortical structures, including the amygdala, while the other (high) requires the PFC.

LEARN MORE: Stress Effects on Neuronal Structure: Hippocampus, Amygdala, and Prefrontal Cortex

LEARN MORE: Prefrontal cortex executive processes affected by stress in health and disease

LEARN MORE: Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function

Most of the time children lack the ability – not the will or desire – to put words to how they are feeling because they don’t have the language yet to express their frustration, anger, fear or lack of understanding during stressful situations. Therefore, their only way of communicating is through hitting, biting or screaming at others.

Can the environment influence a child’s behavior?

Environment has a lot to do with how kids develop into adults.

In fact, research has identified three important aspects of the environment – the physical space, the social-emotional tone, and the routine – that are known to have big impacts on a child’s behavior. The environment sends very powerful messages about how we should behave and feel.

For instance, if a child lives in an abusive or aggressive environment, they might conceptualize their world as unsafe and decide that they need to create their own way of safety and well-being. As a result they begin to develop behaviors or beliefs that are not stable for them. These eventually impact their emotional health, academic performance, and sometimes mental disorders may develop.

A child’s environment plays a key role in how they behave. That is why it is so important for young children to live in safe, loving and nurturing environment. Efforts to foster positive parenting and teaching practices can help protect children’s brains from the detrimental effects of stress and contribute to better behavioral outcomes.

LEARN MORE: Delineating the Benefits of Arts Education for Children’s Socioemotional Development

What are some strategies we can use to deal with challenging or behavioral problems present in young children?

LEARN MORE: Behavioral Interventions for Anger, Irritability, and Aggression in Children and Adolescents

LEARN MORE: An approach to problem behaviors in children

Being involved in NW Noggin this spring term has been so fascinating, fun, exciting and interesting at the same time because I got to explore more about brains and, most importantly, was able to hear children’s questions and their own unique interests at every school.

In fact, at every visit to public schools where I volunteered, I heard deep conversations and questions that sparked my interest in creating a public post for this term. I chose the topic of preschool behaviors; a topic that I enjoyed researching because I got to learn how the stress response correlates to young children’s behavioral issues like hitting, biting, or pushing other friends.

Also, I enjoyed learning about how small children (and in many cases, adults) are driven by strong emotions when frustrated, which is why it’s hard for them to use words and language to express their feelings. Learning this topic is so important for me because I want to incorporate helpful strategies and interventions in my classroom when my students are having a hard time restraining their feelings of anger, irritability and aggressiveness.

I want to thank Bill and Jeff for allowing me to be part of this awesome outreach program, where I met amazing PSU students and heard many interesting questions during our visits to public schools. Overall, it’s so fascinating to see how our brain plays a vital role in controlling many functions necessary for our survival, such as thought, memory, emotion, touch, motor skills, vision, respiration, and behavior.