Post by Angrich Brophy (she/her), pursuing undergraduate studies in Speech and Hearing Sciences, and an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

College students get stressed!

Various external factors can come into play, along with some self-induced ones.

One of my top stressors in college is learning how to balance so many personal and academic demands. I’ve often had to struggle with studying for exams, writing long papers, keeping up with class material and meeting obligations to family and friends – often all within short periods of time.

I’ve learned over the years as a student that there are certain expectations required for this role. We are expected to be studious, responsible, self-reliant, organized, and complete all those exams, papers, and assignments. It has been a journey trying to become a confident learner within our education system. The demands have put me under pressure and the ups and downs of stress.

Nevertheless, I have also discovered the positive aspects of stress. Stress has encouraged me to become more ambitious, effective and driven.

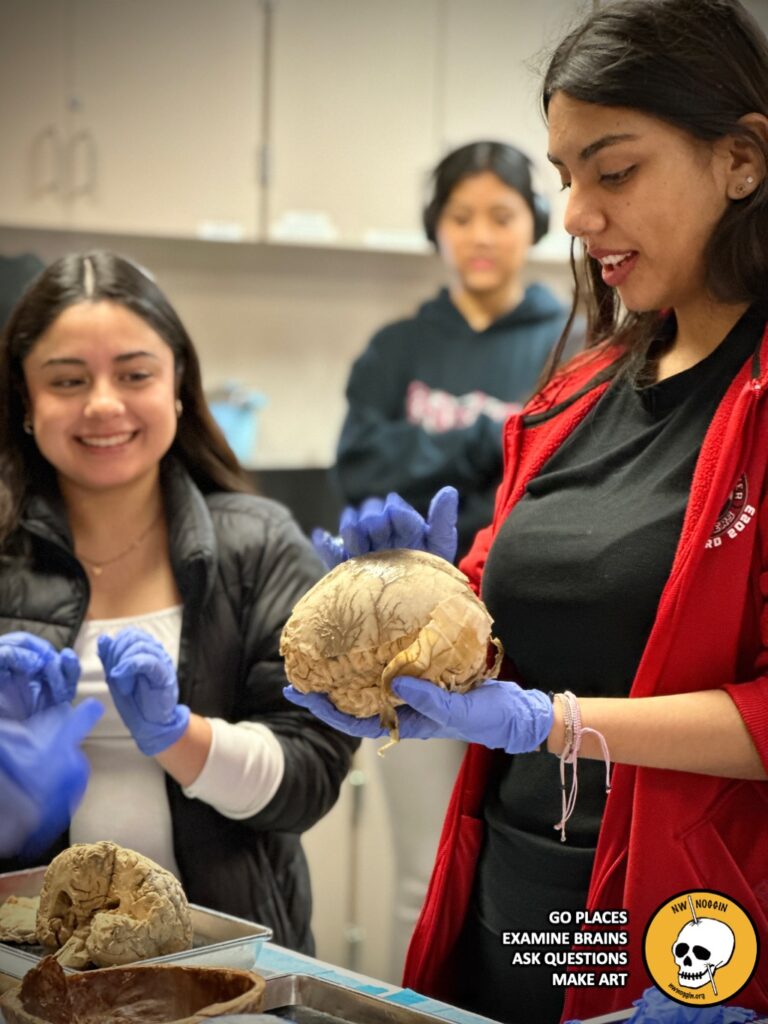

My work with Northwest Noggin began this spring, and let me collaborate with other students studying neuroscience. It was exciting to participate in outreach in schools, correctional facilities and more!

However, before my first outreach event, I definitely noticed my own heightened stress. I even sat alone to try pinpointing exactly what was causing my feelings of anxiousness and noted that my number one worry was that I didn’t know what to truly expect.

Although I had been learning about neuroscience in my undergraduate classes and I’d listened to other students’ experiences with outreach, my feelings of stress were still present because being a volunteer in public outreach was a new role for me. Yet again, despite that stressful tension, I was so excited!

After my first few events I became more at ease with my stress, but I began to observe how stress affected others. Fellow volunteers shared that they too were stressed out and nervous before their first event, but all of it was accompanied by heightened excitement. This was interesting to me because I noticed this sort of stress mixed with excitement in the children we met too!

I really noticed it during one of the activities we introduced, involving the “Human to Human Interface.” I watched as students waited in line, preparing to experience electric shocks and numbness to their arms as someone else “controlled” them. They naturally expressed both nervousness and excitement.

This made me think about how stress can make us excited to take risks, but also a little nervous (and sometimes too anxious to try something, or participate in an activity) when we haven’t yet experienced the outcome of certain situations, and have no clear predictions about what might happen next.

LEARN MORE: Brain Hacking is Electric!

What is stress?

Stress is a physical and/or mental response we have towards external factors (or stimuli) that may occur briefly or for an ongoing period of time. Usually, once the stressor is gone then one feels some relief.

LEARN MORE: Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome

LEARN MORE: Evaluating the Role of Hans Selye in the Modern History of Stress

LEARN MORE: Pre-school behaviors – in the brain!

External factors, often known as “stressors,” can be events or situations that are perceived as stressful by an individual. Stressors can be rooted in the physical environment, and be social/relational, financial, organizational, related to specific life events, choices, or physiological in origin.

LEARN MORE: I’m So Stressed Out! Fact Sheet

LEARN MORE: The good side of “stress”

LEARN MORE: Examples of stressors

The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis

Stress can provoke strong physiological responses in our brains and bodies.

The HPA Axis refers to our hypothalamus (H), pituitary gland (P) and adrenal glands (A).

The HPA Axis is a neuroendocrine communication system that uses hormones to establish connections between the brain and body. The HPA regulates our stress response through the release of hormones, chemicals released into the bloodstream that can have multiple effects throughout the body.

Activity often begins in the hypothalamus, a structure located above the brainstem. Under stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (or CRH). The pituitary gland, which sits below the hypothalamus, is then signaled by the CRH to release the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream to reach the adrenal glands that sit on top of our kidneys. The ACTH leads the adrenal glands to release additional hormones, including one known as cortisol.

Cortisol helps us cope with acutely stressful circumstances, partly by sending glucose to the brain for energy and sustaining alertness. As cortisol rises, it generally inhibits further release of CRH from the hypothalamus, thus lowering ACTH and cortisol release, and bringing HPA Axis activity down.

LEARN MORE: Physiology, Cortisol

LEARN MORE: Pre-school behaviors – in the brain!

LEARN MORE: Why do we think too hard?

Stress on the Brain: Good or Bad?

When you hear the word “stress”, do you immediately think about all of the BAD STRESS that you’ve experienced? There are a lot of negative associations with this word, and we often hear in our society and media only about the bad side of stress.

But, importantly (and perhaps surprisingly), stress can also be a GOOD thing!

Good Stress (Eustress)

Good stress is recognized when it drives a person to become motivated to achieve a goal, such as participating in a job interview or successfully applying for an educational program. Stress that helps us cope effectively or leads to beneficial outcomes is technically known as eustress.

“Although the term ‘stress’ carries a negative connotation, evidence suggests that under certain circumstances, stress exposures may have the potential to enhance an organism’s performance and resilience…”

— Kirstin Aschbacher et al (2013)

Bad Stress

Bad stress, also known as distress, is linked to less positive outcomes, in some cases inhibiting participation and engagement in new, challenging and potentially beneficial activities.

I know that I’m often stressed by the fear of making a mistake. Mistakes are often associated with “failure” and tend to have negative cultural connotations. As a result, our society expects us to avoid mistakes. This is probably a major reason why students experience distress and fear in school, and sometimes avoid taking useful risks.

As a student I know the distress of potentially failing an exam; yet, in some cases, one is able to move forward from such a stressful occurrence with sufficient resources, personal resilience and supportive relationships. A contradictory outcome would be experiencing such a stressor without an adequate support system or resources, which can lead to poor sleep and other unhealthy consequences.

But mistakes are important, and experiencing challenges and failure provides opportunity for reflection, changes in our perspective, new questions and sometimes innovative solutions. Celebrating and sharing our own mistakes with students is a way for us to address the cultural expectations we hold that have often contributed to student stress and fear about taking more positive risks.

LEARN MORE: Science students’ perspectives on how to decrease the stigma of failure

LEARN MORE: Good Stress, Bad Stress and Oxidative Stress: Insights from Anticipatory Cortisol Reactivity

LEARN MORE: School Stress: How Student Life Affects Your Teen

LEARN MORE: Students Experiencing Stress

Stress in the school environment

Students from all educational levels can face and experience stress.

I believe that schools should promote the good side of stress in order to boost motivation, improve academic performance and remain manageable. When the academic environment is perceived by the student as threatening, or a risk to their health, and the demands become unmanageable, the eustress has turned into distress. Research reveals that distress among students can lead to a decrease in academic self-efficacy, procrastination and even avoidance of school and school work.

Again, stress can be good when it’s manageable and motivating. It can be particularly good for adolescents for growth and building resilience. Eustress can pave the path for academic success, higher self-esteem and new skills. However, it’s also important to recognize when stress becomes unhealthy, especially within our school systems.

What are some sources of stress in school?

Students typically report feeling distress due to excessive amounts of homework, assignments and exams. The school curriculum is a primary sources of distress, particularly when students have to memorize complex or irrelevant material and navigate subjects chosen by academic professionals or state school boards (instead of integrating some of their own motivations and interests), while keeping up with classwork. Sometimes teachers, often under stress from administrators and school districts, impose unreasonable expectations on students, don’t listen, and don’t communicate or connect.

Other stressors that may impact student stress include social pressures, being tired, and balancing a busy schedule on top of school.

School start times have a huge impact on adolescent stress, mental health and academic performance – so much so that simply delaying the start of high school by an hour can have profoundly beneficial effects, turning a lot of distress into eustress!

LEARN MORE: Hey Vancouver: Let Kids Sleep!

LEARN MORE: Trapper Keeper!

LEARN MORE: School-Related Stressors and the Intensity of Perceived Stress Experienced by Adolescents in Poland

LEARN MORE: Addressing Adolescent Stress in School: Perceptions of a High School Wellness Center

LEARN MORE: HOW TO MANAGE STRESS IN SCHOOL AT EVERY GRADE LEVEL

LEARN MORE: Divisive Politics Are Harming Schools, District Leaders Say

What is going right in classrooms?

Teachers can serve as an important protective factor in preventing long-term distress by motivating their students, valuing their achievements and making sure they understand the content before moving to the next lesson. Teachers can also work to address the issue of students picking on each other in the classroom in order to build better classroom learning environments.

School-based intervention programs can be effective at reducing adolescent stress.

One of the significant observations that I made at each school I visited was that the staff and teachers appeared to have developed strong relationships with their students.

I saw both elementary and high school teachers allow space for students to ask us questions and ensure that everyone had a chance to participate. Staff and teachers had positive interactions with their students and facilitated conversations to learn about their interests and what activities they enjoyed during our events. These strong relationships serve as an important protective factor for stress reduction in students.

Schools can also enhance eustress by providing students with more information about what to expect; for example, when moving up a grade level. They can let students know what subjects they’ll study, how many teachers they will encounter in a day, what to expect with peers, and whom to talk to if they have a problem. This kind of information could reduce some of the anticipation-related, “not knowing” stress.

LEARN MORE: How teacher and classmate support relate to students’ stress and academic achievement

LEARN MORE: What Types of Educational Practices Impact School Burnout Levels in Adolescents?

LEARN MORE: Coping with the Stress through Individual and Contextual Resilient Factors in Primary School Settings

During one outreach event at a local Portland high school I sat down with a small group of students to explore the structure of the neuron by making it out of pipe cleaners. As I sat down, one student pointed to my already crafted cell and said, “I want to learn how you made that neuron!” It was clear that they were excited to participate in this activity.

We began the process of building our own cells. This gave us a chance to get to know one another and share how the school year has been going. Making art together certainly allowed us to learn about the science of neurons, but also about each other. It was a profoundly stress-relieving activity!

“Engagement in creative tasks also activates the hippocampal cortex in the limbic system–increasing alpha and theta brain waves associated with relaxed states, meditation, and memory retrieval”

— Supporting youth mental health with arts-based strategies: a global perspective

LEARN MORE: Pipe Cleaner Brain Cells!

Policy changes beneficial to the adolescent brain

Classroom interventions can benefit adolescents if they are aimed at developing skills that enhance self-esteem, introspection, problem solving, stress management and coping.

Such programs can also help create community by letting students get to know one another better and build better classroom environments. The arts can help tremendously. Other interventions that research finds beneficial are courses that teach time management skills, greater access to health professionals, and the availability of social work practitioners to support psychosocial education about stress management and who can help teach relaxation exercises to promote eustress.

The “Double Reduction” Policy in China

School stress comes from various factors.

The “Double Reduction” policy was first implemented in China and aimed to lessen the amount of homework and after school tutoring. The goal was to reduce academic pressure on students and lower the excessive financial spending on tutors. According to research, this policy benefited student mental health, improved sleep, and provided more time for parental involvement and outside activities, due to the reduction of academic distress from school.

LEARN MORE: Has the “Double Reduction” policy relieved stress? A follow-up study on Chinese adolescents

LEARN MORE: School Stress Takes A Toll On Health, Teens And Parents Say

Research also suggests ways that we can help ourselves avoid distress. Individual practices for reducing our stress include meditation, yoga, adequate sleep, relaxation techniques, healthy eating, connecting with others, journaling and counseling.

LEARN MORE: Reducing Stress

LEARN MORE: Mind and Body Approaches for Stress and Anxiety: What the Science Says

LEARN MORE: Stress management

My own experiences and cultural expectations initially led me to believe that I had to manage all the academic stress on my own. Through outreach and research I’ve learned that we can avoid distress and promote eustress. Schools make a big impact when they celebrate mistakes, offer meaningful and relevant assignments, reduce homework, integrate art and provide adequate resources for student well-being.