On a sunny, flowering, pollen-dense spring day, eighteen Noggin volunteers from Portland State University happily converged on Sunnyside Environmental School in southeast Portland. The school was bursting with activity, as students, teachers and staff were readying plants for a sale, while we carried in our pipe cleaner astrocytes, cerebellar granule cells, 3D printed cochleas and buckets of brains!

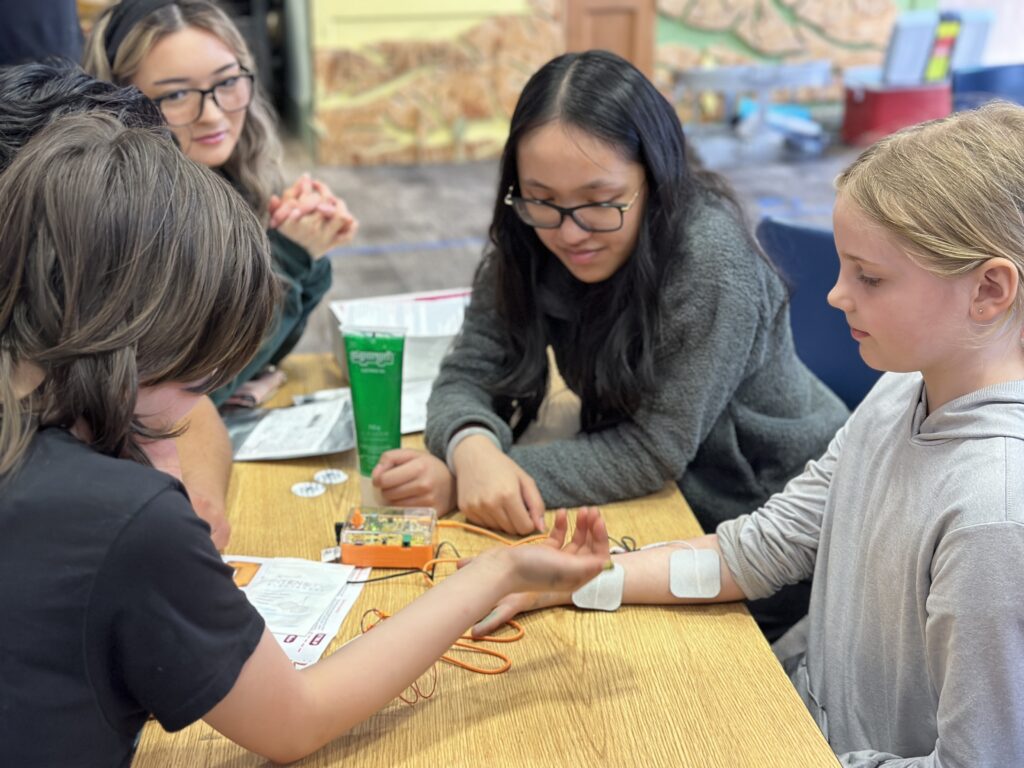

We’d also received a brand new Human to Human Interface from Backyard Brains, thanks to generous support from the Dean’s Office at the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at PSU!

So we set about unpacking and testing out this shocking new device!

“I noticed a lot of mixed emotions with this activity, including excitement, some nervousness and sometimes a sense of being overwhelmed! I think it was intriguing to a lot of kids (and adults) because we are so used to having control over our own movement. Our nervous system’s purpose to send messages from our brain to tell our body what to do is not something that we often stop to think about. With this, it was especially intriguing to have another person be ‘in control’ of your own arm. From my experience with this, my arm felt like it was receiving shocks of numbness! Overall, it was really fun to learn and observe how it’s possible to send electrical signals from our brains with this device, which carried over electrically to move another person’s arm!”

— Angrich Brophy, Interdisciplinary Neuroscience @ Portland State University

LEARN MORE: Brain Hacking is Electric!

We’ve visited students at Sunnyside for years now, through pandemics and more, exploring everything from the glory of glial cells to how to change our habits and acquire new skills!

LEARN MORE: Learning through mistakes!

LEARN MORE: How to visit public schools

LEARN MORE: Thank You Northwest Noggin!

LEARN MORE: Neurons in Minecraft & More!

LEARN MORE: A crayon in Homer’s brain

LEARN MORE: What about the glia?

This time our brainy volunteers included Angrich Brophy, Diego Sanchez, Alyssa Showalter, Cris Keirsey, Pearl Ton, Shae Zeimantz, Cat Swallow, Elizabeth DeGraw, Ben Johnston, Rocio Garcia, Melissa Garcia, Kadi Rae Smith, Hannah Hauser, Xander Hawkins, Iris Campos Servin and Daren Kostov, all from the burgeoning neuroscience bastion of Portland State University!

We started with introductions – and questions!

The 4th graders in Jeremy Thomas and Asa Gervich’s classes are studying the brain this spring (despite federal and state science teaching standards that largely leave it out) and were as familiar with important structures like the hippocampus, amygdala and frontal cortex as many of our volunteers! And they had lots of questions.

How do we remember and is there a limit to how many memories we can have?

Can we learn to control our autonomic nervous system?

How does sleep deprivation affect the brain?

Can you survive without sleep?

“No, it is not possible to survive without sleep. Sleep is remarkably important for us and it plays a significant role in various physiological processes and aspects of our lives. For one, it has a great influence on attention, cognition, and mood. According to a peer-reviewed article, sleep is critical ‘for the ability to think clearly, to be vigilant and alert, and sustain attention’ (Worley, 2018). Additionally, studies have shown that sleep deprivation can lead to negative mood changes, such as increased stress. Sleep deprivation may affect the ‘processing of emotional memory – in other words, our tendency to select and remember negative memories after inadequate sleep’ (Worley, 2018). Perhaps, you have experienced this before with yourself or someone who is not a morning person and has had inadequate sleep. Sleep also repairs and restores the body. It strengthens the immune system and regulates hormones, repairs tissues and consolidates memories. From the abundance of published research on sleep, it is safe to say that sleep is essential for one’s health and survival.”

— Diego Sanchez, Interdisciplinary Neuroscience @ Portland State University

LEARN MORE: The tired hippocampus: The molecular impact of sleep deprivation on hippocampal function

LEARN MORE: The impact of sleep loss on hippocampal function

LEARN MORE: Hey Vancouver: Let Kids Sleep

How do we dream and what are dreams for?

LEARN MORE: Noggins in Nod: The Science of Sleep

LEARN MORE: Nocturnal Mnemonics: Sleep and Hippocampal Memory Processing

LEARN MORE: Memory and Sleep: How Sleep Cognition Can Change the Waking Mind for the Better

LEARN MORE: Impact of Sleep Quality on Amygdala Reactivity, Negative Affect, and Perceived Stress

Is it possible to think too hard?

LOVE THIS QUESTION! This needs to become its own post (coming soon!)

What would happen without an amygdala? I wish I had a switch to turn mine on and off!

“The thing that got me was the discourse on the amygdala from the second group. The first student asked ‘What would happen if someone didn’t have an amygdala?’ and we asked ‘What do you guys think would happen?’ Then one student responded, ‘I think she wouldn’t feel fear,’ and another student said, ‘But would she know what fear is?’ – which launched a whole conversation about the difference between the viscerally felt experience of a feeling and more abstract knowledge about it. Very cool classes!”

— Kadi Rae Smith, Portland State Neuroscience Club

Remarkably there is a documented case of a woman without any amygdala (there is usually an amygdala in both your right and left hemispheres, and she had neither), so we now have some preliminary answers to these intriguing questions!

Patient SM has Urbach-Wiethe disease (a.k.a. lipoid proteinosis), a rare inherited disorder than impacts skin, but can also lead to calcium deposits collecting in blood vessels that feed the amygdala and surrounding areas in the brain. Without adequate blood flow, the amygdala may be damaged, and intriguing changes can result.

Researchers tried all sorts of ways to induce fear in Patient SM.

Imagine yourself experiencing the following during a research study: “To provoke fear in SM, we exposed her to live snakes and spiders, took her on a tour of a haunted house, and showed her emotionally evocative films…” (Feinstein et al, 2011).

LEARN MORE: The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear

LEARN MORE: Translational neuroscience of amygdala lesions: Studies of Urbach-Wiethe disease

LEARN MORE: What have we learned from Patient SM about fear and the amygdala?

LEARN MORE: Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala

LEARN MORE: What is Urbach-Wiethe disease?

Curiously while Patient SM can define fear, and use fear-related words correctly in a sentence, she does not feel fear. Her heart doesn’t race when a spider falls on her hand, or even when someone once tried to attack her with a knife! In fact, frightening situations appear to provoke arousal in Patient SM (as they do in most of us) – but without the fear that would lead you or me to avoid threatening situations. Patient SM, in contrast, gets curious and approaches! Learn about the knife incident (and more!) here:

Her inability to feel fear, however, makes it challenging for Patient SM to create an image of fear. When asked to draw differing emotions (happiness, sadness, surprise, etc), she exhibited selective difficulty with drawing fear, ultimately producing a drawing of a baby seen from the side.

LEARN MORE: Fear and the Human Amygdala

While Patient SM exhibits little fear of external threats, internal threats cause fear and panic!

One huge threat to humans is a lack of oxygen, which can cause suffocation and death. Yet we don’t directly detect oxygen levels, but we’re very sensitive to carbon dioxide. So if we are breathing a mixture of sufficient oxygen, and the CO2 levels are artificially increased, we can detect that increase and suddenly feel like we’re not getting enough air! How would you react in that situation?

“Decades of research have highlighted the amygdala’s influential role in fear. Surprisingly, we found that inhalation of 35% CO2 evoked not only fear, but also panic attacks, in three rare patients with bilateral amygdala damage. These results indicate that the amygdala is not required for fear and panic, and make an important distinction between fear triggered by external threats from the environment versus fear triggered internally by CO2.”

— Feinstein et al (2013)

LEARN MORE: Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage

So your amygdala is tuned to threats from outside (like a spider, or a knife!). Yet even those individuals without an amygdala, who will pick up huge snakes and walk down dark alleys without concern, can still feel fear and panic from internal, bodily threats like a perceived lack of air.

ALSO: There have been successful attempts to alter amygdala activation in those suffering from panic or post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)! Brain networks involving your prefrontal cortex (PFC) can develop effective inhibitory control your amygdala as you grow up, helping you to regulate your emotions. Efforts to train or stimulate these areas have proven beneficial.

LEARN MORE: Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms

LEARN MORE: What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

LEARN MORE: Eye-Movement Intervention Enhances Extinction via Amygdala Deactivation

HUGE THANKS to all the students and teachers at Sunnyside Environmental School for their thoughtful and compelling questions, gorgeous art and excitement for brains! And thank you Northwest Noggin volunteers for sharing your expertise, curiosity and enthusiasm!