Post by Frederick Schemel, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University. Frederick is currently a research assistant in the Developmental Brain Imaging Lab (DBIL) run by Dr. Bonnie Nagel in the Department of Psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

March of the Multitudes

Neuroscience is not an easy topic to dive into.

I joined ongoing research about neural and cognitive development as a relative beginner, and it seemed daunting. As an inexperienced associate, I was even a little scared. A laboratory is a professional setting on the forefront of discovery and I had a strong sense that it would not tolerate incompetence – including mine!

The joker in me then asked why I was even there, but that hardly feels appropriate.

So in my experience, when you crest that hill (Pill Hill!) and approach the realms of knowledge that are gated by research you feel like you are joining the select few who are the masters of humanity’s fate and knowledge. You feel like an arbiter of discovery, yet research does not occur in one step nor by the hands of one person alone. It is not just a few towering figures working independently to usher in change. Nor is it always just one lab full of scientists. Like raising children, I learned, research also takes a village.

So why did it feel to me like a field that only strives to serve a select and privileged group of people? Why did I feel unqualified, and even unwelcome? Why did I see it like this when I first arrived?

Real research involves a lot of different people!

An actual research lab, I discovered, employs many different people (sometimes hundreds!) for a multitude of tasks ranging from collecting data (this is what I’m doing), processing data, analyzing data, designing experiments, and many administrative responsibilities, most of which don’t require the same stringent scientific background that I envisioned in my initial stereotypical view of a lab.

LEARN MORE: Research Team Structure

Okay, so perhaps that makes sense – but labs don’t get so big that the actual research scientists are vastly outnumbered by all the non-primary investigators (non-PIs) like me. Right??

Well, as a current member of a lab that is working on a multi-institutional consortium study, I can attest that in all of the labs I’ve seen the investigators are drastically outnumbered by research assistants, lab managers, data scientists, other staff and volunteers. The roster in any lab includes lots of people with many different skill sets and capabilities. And all of them are valuable for what they contribute.

To get to the end of a somewhat belabored point, research involves many people and requires individuals with a wide range of backgrounds, so you shouldn’t write it off just because you lack the ‘right degree or training.’ These are myths that we tell ourselves that sometimes stop us from doing what we want. For me, that was the chance to contribute to exciting brain research in people.

The value of diversity in research

The value of diversity in research labs is pretty clear to me now.

Yet I think there is value in looking into what diversity specifically offers in research environments and how the promotion of diversity may expand opportunities for the future of neuroscience research. People with diverse backgrounds (in education, for example, or culture or personal immutable characteristics) bring different thoughts and perspectives that can inform more universal conclusions or ways of engaging with the challenges present in research.

From my experience at DBIL, I feel that to innovate and make progress, we should promote diversity, by including creative people and those not currently overrepresented in science who approach research questions and communicate ideas in compelling and effective ways.

We need individuals who can bring wider accessibility of discovery, writers who can challenge the monotony of typical papers, and those with a myriad of other backgrounds who can shape both the product and production of research.

“Research shows that diverse teams working together and capitalizing on innovative ideas and distinct perspectives outperform homogenous teams. Scientists and trainees from diverse backgrounds and life experiences bring different perspectives, creativity, and individual enterprise to address complex scientific problems.”

— NIH Program to Promote Diversity in Health Research

LEARN MORE: Diversity and Scientific Excellence

LEARN MORE: Achieving a Diverse Neuroscience Workforce

LEARN MORE: NINDS Strategies for Enhancing the Diversity of Neuroscience Researchers

LEARN MORE: WORKPLACE DIVERSITY AND ITS IMPACT ON PERFORMANCE OF EMPLOYEES

LEARN MORE: New directions for research and practice in diversity leadership

So let’s talk about my current research.

Right now I’m working in the Developmental Brain Imaging Lab run by Dr. Bonnie Nagel, who is in the Department of Psychiatry at OHSU. The lab investigates how a host of specific factors contribute to the development of brains and what effects those factors have in adolescent and adulthood.

LEARN MORE: Developmental Brain Imaging Lab

The research ranges from pain processing and the risk of substance use disorders to general neurodevelopmental health. I am working on the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a consortium study that involves 21 separate labs across the country, each gathering or processing data and analyzing it for their own research ends. It is an exciting project, involving discovery of the nature of the developing brain and what it can tell us about brain structure and function and the emergence of developmental disorders.

LEARN MORE: Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study

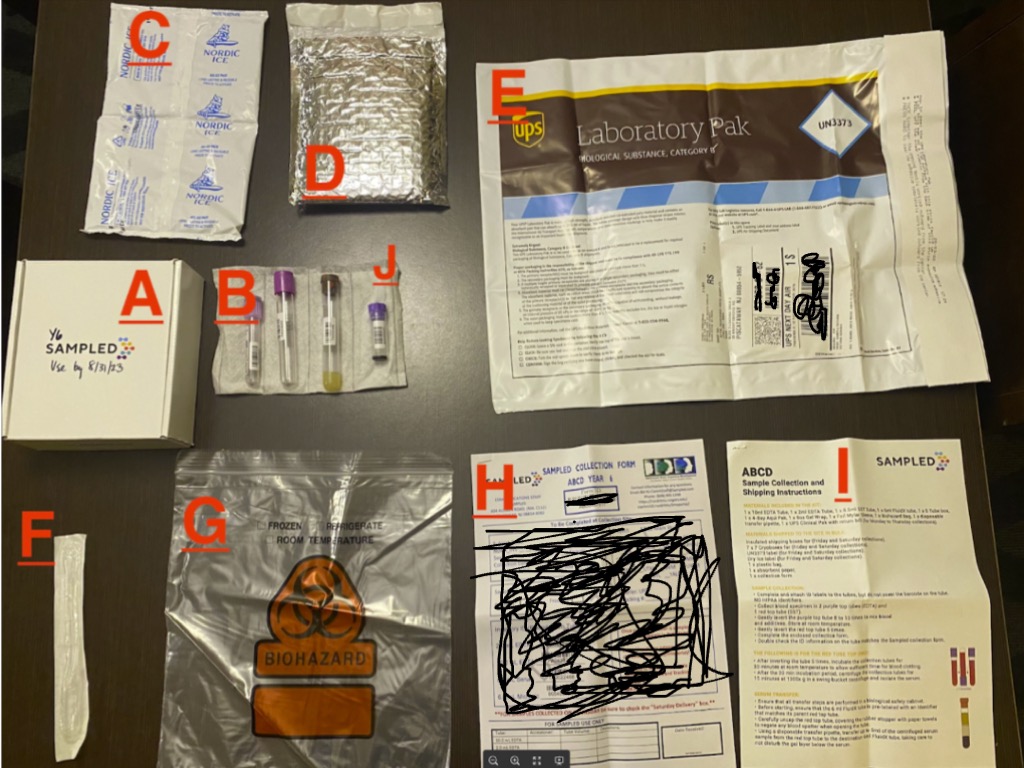

ABCD is currently in year seven of data collection, and analysis shows the breadth of what is possible, with many teams working on getting new up-to-date biometric and neural information from the study’s growing subject population. This involves taking samples from many sources including hair, teeth, saliva, general activity through Fitbit use, and blood amongst others. We are tracking a wide variety of information including DNA, hormones, health measures and more.

LEARN MORE: Sociodemographic Associations With Blood Pressure in 10-14-Year-Old Adolescents

Tracking a BLOOD sample!

Tracking a single sample is a good way to show the interconnected pathways of this research endeavor and how many hands are involved in the findings of a study.

Taking a blood sample seems like an easy thing to do right?

Well first you have your subject – PERSON 1 in this example.

Then you need the research/lab assistant (the RA) who takes their sample (PERSON 2).

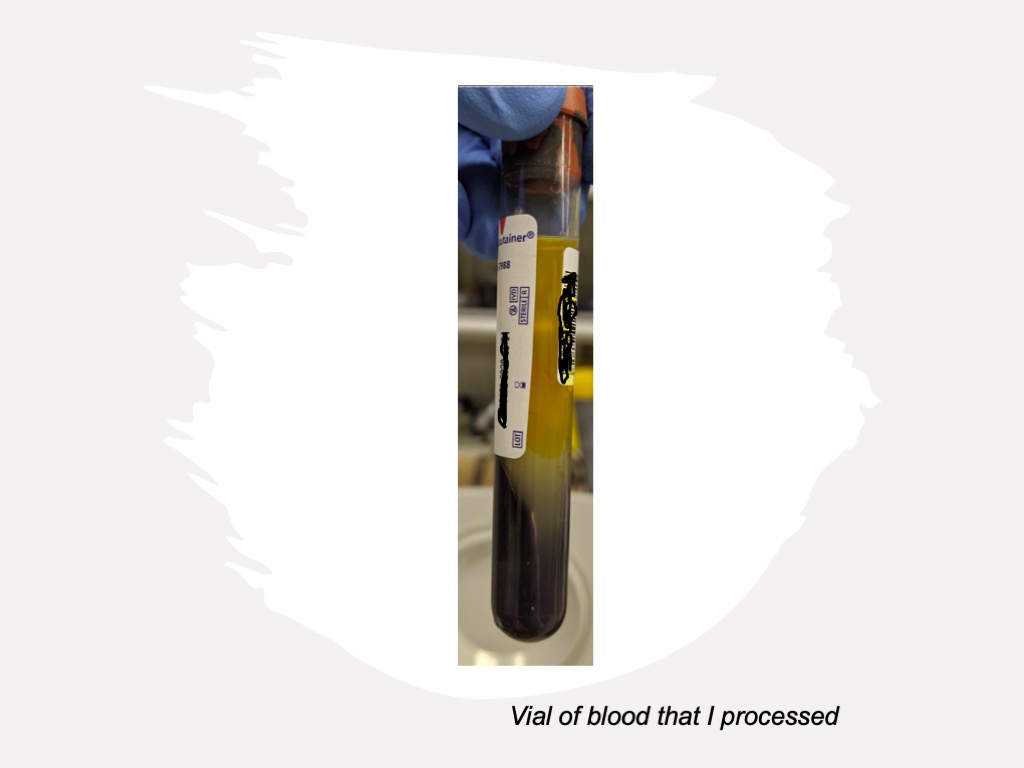

The RA prepares the subject for a blood draw, removing anywhere from 20.5-22.5 ml of blood, and moving it into 3-4 vials. Then the RA needs to process these samples and input the results into the computer system, including specimen and subject information details (for example, when the blood was taken, which participant it came from, what study is it a part of, and any additional specific characteristics required).

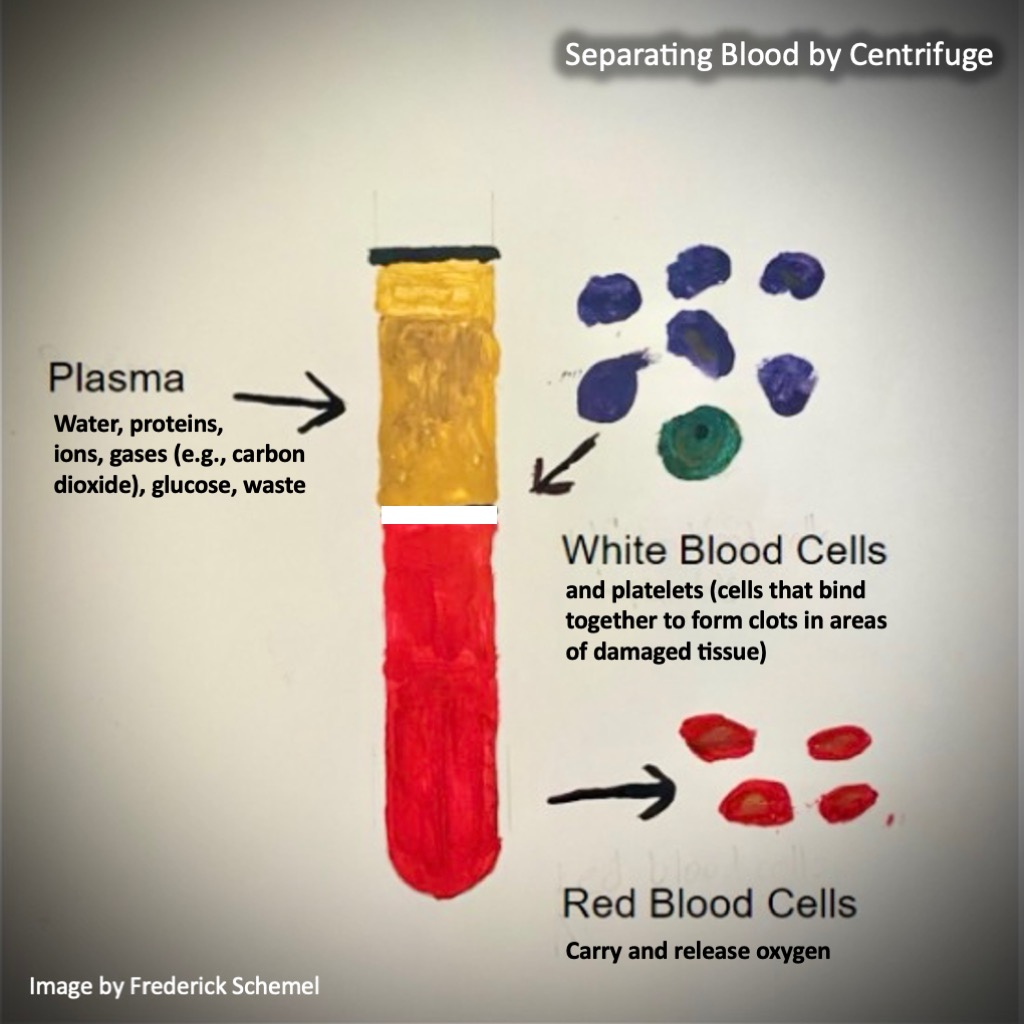

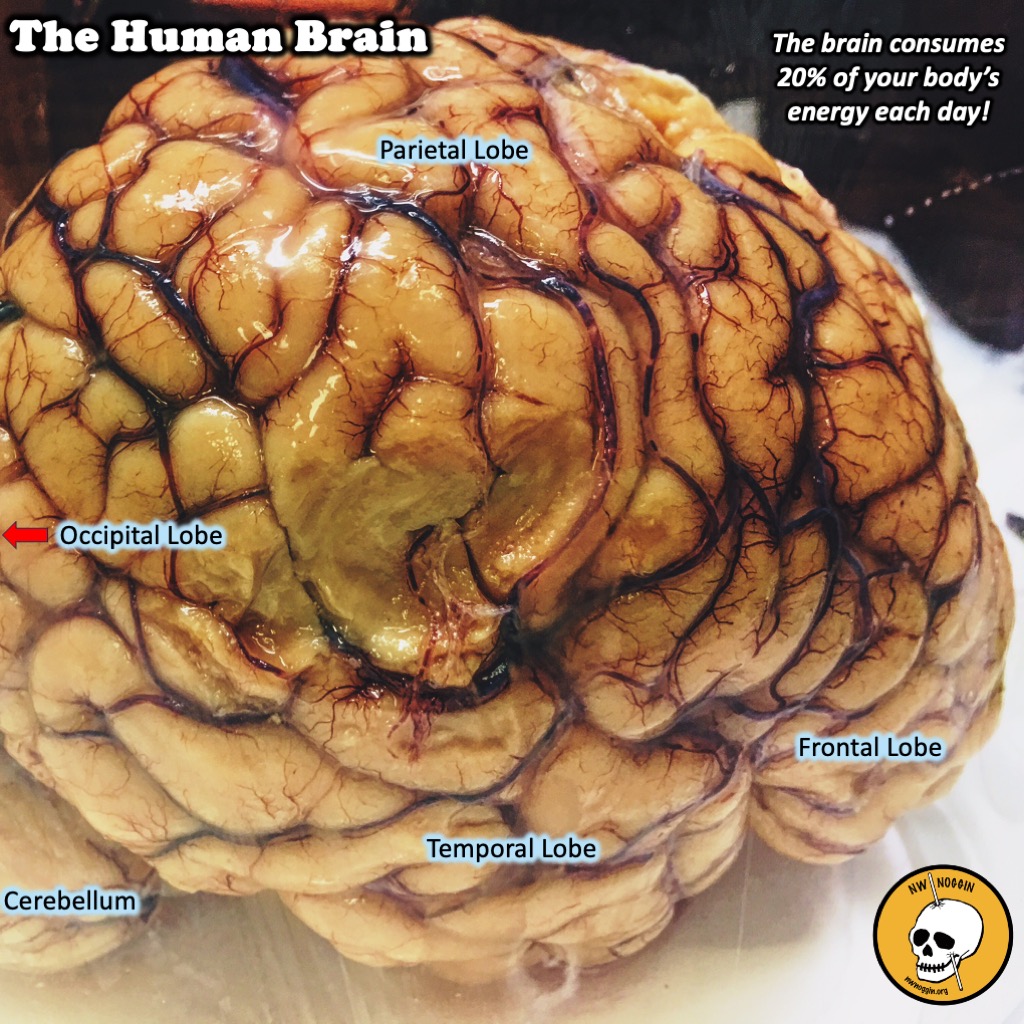

What blood processing leads to in those vials of blood: What do the different areas contain?

Processing blood requires centrifuging and removal of serum (the fluid in blood without cells or clotting factors), or the separation of white blood cells, red blood cells and plasma (the water, ions, proteins, carbon dioxide, glucose and clotting factors) from a sample. This involves a different research collaborator (often ME!) adding PERSON 3 to the list.

LEARN MORE: Collection, storage, shipment of specimens for laboratory diagnosis & interpretation

LEARN MORE: Differences between Human Plasma and Serum Metabolite Profiles

LEARN MORE: Serum or Plasma (and Which Plasma), That Is the Question

LEARN MORE: Fractionation of Cells

This serum from the red blood cells is put into its own vial, and thus multiple tubes are sent off to a phlebotomy lab for analysis. This of course involves a whole new team which we will charitably call PERSON 4 (though there are likely several more people involved in this step).

LEARN MORE: Phlebotomy

LEARN MORE: Best practices in phlebotomy

When analysis is complete, the information gets added to the total information pile, better referred to as the data set, and then investigators try to draw their conclusions from it, adding PERSON 5.

Five is the fewest number of people that could exist in such a scenario. Out of these five people, maybe one or two fall into the category that most people might think of as research scientists.

LEARN MORE: Red Blood Cells: Chasing Interactions

And five is too few! There are many more people not included in my description. Labs employ people who manage personnel and assist with subjects in other ways, and data scientists who analyze data who could also have been added to the chain – a plethora of people contributing to the work of science that are not always mentioned when considering how neuroscience research gets done.

Why am I saying this?

I want people to realize that there is no one path to being a researcher, nor is there just one way to be a researcher. If you’re curious about scientific research, YOU can reach out and pursue it too.

LEARN MORE: What is research like?

LEARN MORE: Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor @ Portland State University

LEARN MORE: How did we get an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor @ Portland State University

LEARN MORE: Volunteer Opportunities in Research @ OHSU

LEARN MORE: A Legacy of Links

LEARN MORE: Northwest Noggin Collaborators!

A researcher has a curious mind and uses it to explore and sometimes challenge the biases and paradigms of today with information of tomorrow and the only way to actually be one is to try. The field should not seem daunting nor should it scare you off. It ought to be something that many people should be even giddy to join and investigate, regardless of their personal background.

I have met many people who haven’t extensively studied hard science but are nonetheless valued contributors to research in neuroscience, including artists, writers, social workers and more. All are (or should be) welcome, as I’ve learned that there are opportunities to participate in research design and execution, and create a more holistic picture of what can be and is possible in science.