Post by Andy Ng, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University. Andy is a welcome and regular contributor to outreach visits through Northwest Noggin.

On average, a young citizen of the United States spends 180 days a year at school, for at least 6 hours a day. From 1st to 12th grade, this translates to approximately 2160 days or at least 12960 hours. Although school is lauded as an educational place, are we really tapping into our greatest potential or are we wasting away and weeding out certain futures?

I’m going to be totally honest, I hated school when I was younger, I hate school now, and I will always hate school.

Ok, so maybe hate is a strong word.

But I always felt so limited sitting at a desk. Instead of listening to the teacher talk about some irrelevant fact, I would always sway my head and fall into what some would call maladaptive daydreaming. I would envision myself swimming with tropical fish, flying with eagles, and sculpting vases with elephants.

“Sometimes when you start to ramble

― Anis Mojgani, Poet Laureate of Oregon

or rather when you feel you are starting to ramble

you will say Well, now I’m rambling

though I don’t think you ever are.“

LEARN MORE: A Mind Free to Wander: Neural and Computational Constraints on Spontaneous Thought

LEARN MORE: Towards a Neuroscience of Mind-Wandering

LEARN MORE: Wandering Minds with Wandering Brain Networks

LEARN MORE: The brain on silent: mind wandering, mindful awareness, and states of mental tranquility

LEARN MORE: The Critical Role of the Hippocampus in Mind Wandering

LEARN MORE: Wandering minds and ADHD: Brittany Alperin unpacks the relationship

Science has observed and recorded the amazing changes in our brains as we grow and develop. Babies start out with billions of neurons, which reach out and connect with each other, forming networks. As we each experience the world, learn, and participate in different hobbies or activities, our neurons encode our understanding of such tasks in new neural pathways that are reflective of that learning.

For example, someone who is particularly gifted at learning languages would have different neuronal pathways than someone who is an experienced dancer.

LEARN MORE: The Basics of Brain Development

LEARN MORE: The Cellular and Molecular Landscapes of the Developing CNS

LEARN MORE: Myths and truths about the cellular composition of the human brain

In many respects, I was being limited at school.

By spending hours and hours meeting high academic expectations and setting a perfect attendance record, I missed out on different opportunities, experiences and hobbies. I had ideas I wanted to check out, new things I hoped to discover, but I had to take boring, stressful, biased tests and “prove” myself. My brain lost out on developing different neural pathways and connections that might have created the skills and memories I wanted. I had to cut out exploring my own interests in lieu of getting what I now see as useless A’s on a piece of paper that I naively thought measured my self-worth.

“Scores from the SAT and ACT tests are good proxies for the amount of wealth students are born into.”

― Ezekiel J. Dixon-RomÁN, Howard T. Everson, and John J. Mcardle

LEARN MORE: Testing, Stress, and Performance: How Students Respond Physiologically to

High-Stakes Testing

LEARN MORE: More Testing Means More Stress For Teens — And There’s No Solution In Sight

LEARN MORE: Sex differences in stress responses: social rejection versus achievement stress

LEARN MORE: Cognitive fatigue influences students’ performance on standardized tests

As the body develops from childhood to late adulthood, the brain will trim away potential neuronal pathways that are not needed, not utilized, too active or not active enough. This is an incredible period of change and development, with our brains plastic (changeable) enough to acquire skills in so many areas. It helps to be intrinsically motivated – to want to explore and learn more about something.

“Intrinsic motivation was the strongest predictor of achievement…”

― Ioannis Katsantonis, Ros McLellan, and Pablo E. Torres

LEARN MORE: New neural activity patterns emerge with long-term learning

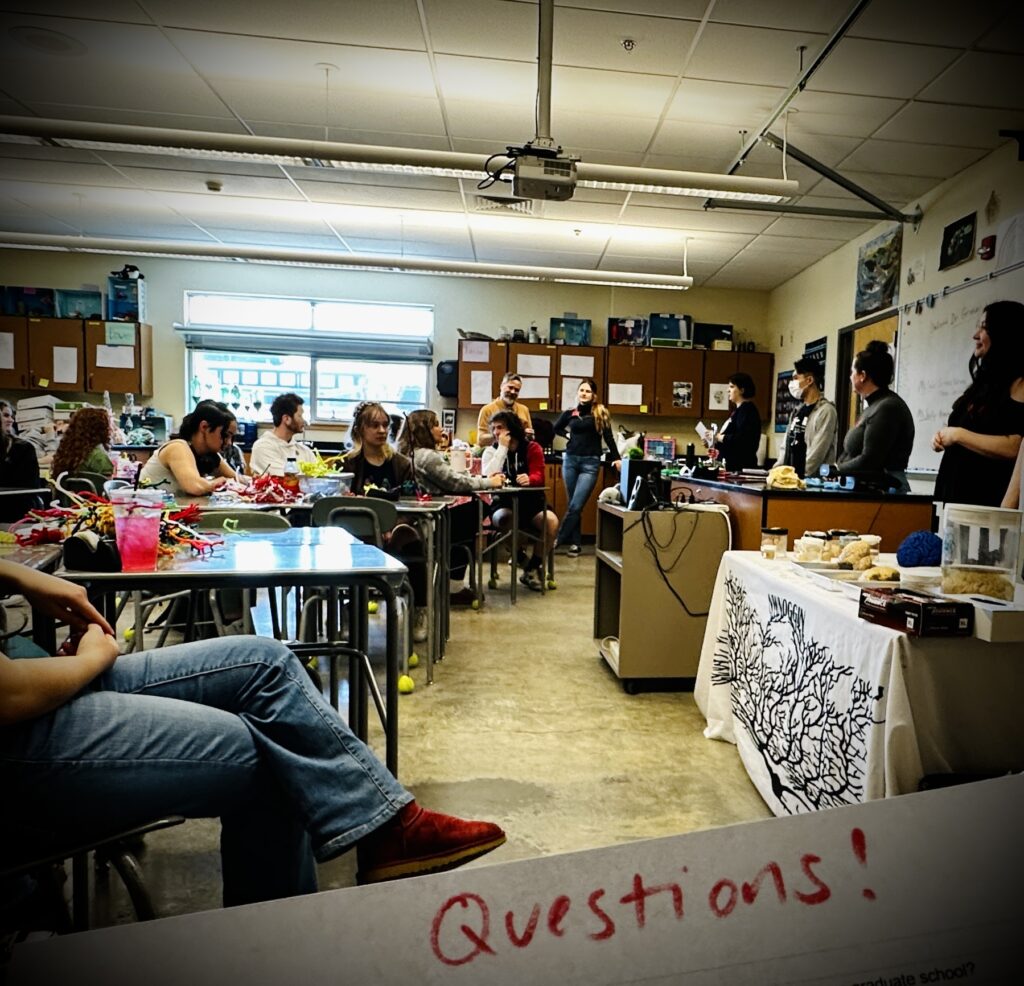

I was never particularly bothered by this as I thought that as long as I got the letter grades I wanted, I would develop the synapses I’d both need and appreciate. Unsurprisingly, I was wrong. It wasn’t until I visited Oregon City High School to showcase brains and met Alyssa (name changed for anonymity) that I really felt I had missed out in high school.

I suddenly felt like I was so encumbered with getting a tiny alphabetical letter that I discarded real opportunities for beauty and art. Unlike me, Alyssa threw herself into her art. She wasn’t obsessed with grades. Alyssa crafted portraits of people that were like mirrors on paper. She drew cartoon characters that were powerfully reflective of her emotions. She used her art as a space to explore and understand herself. Through her art, she showed emotional regulation skills that I could only dream of.

I don’t see myself as a particularly jealous person, but I was jealous.

I was jealous that she knew how to turn paper and pencil into something that people would muse at for hours. I guess you already know what I’m implying. I can’t draw. Well, to be more specific, I can’t art. The art does not art for me. This feeling was extremely exacerbated by seeing Jeff Leake, Noggin’s resident artist extraordinaire, teaching students how to make pipe cleaner neurons. Let me just preface this to say that I definitely don’t have the fine motor skills to make a neat neuron like everyone else did.

LEARN MORE: Pipe Cleaner Brain Cells!

Despite fretting over Alyssa’s art and how I wished I had her ability, she was quite humble in response. She explained that she wasn’t “gifted” this skill. Rather, she practiced (and practiced!) until she got to the point where she liked it. She made a lot of mistakes. Just like anything, it’s work. But rewarding.

From a neuroscience perspective, she and Jeff spent hours developing, maintaining, and strengthening the neural pathways required to exhibit such dexterity. They had to make and accept and learn from lots of errors too – something that school doesn’t often sanction, especially if you wants A’s. It’s safe to assume that their brains developed more artistically useful pathways than mine, because of their experience. And I wish I had developed such skills, instead of stressing about grades in school.

LEARN MORE: Learning through mistakes!

Alyssa tells me that I can always start learning now.

I fear that I might never reach Alyssa’s level of artistic competence. I’ve barely begun practicing, so I already know that my brain won’t necessarily build the neural pathways as quickly or as well as someone younger. I’ve learned that, as people age, the rate of neurogenesis, creating new neurons, declines and may even come to a halt. Even more, the brain is usually what declines first, leading to losses in memory, abstract thinking, and overall cognition. Our disappointing decline as people, and even who we are as an individual, is linked to a thinning cortical density, neurons dying, the relentless trimming of unneeded or unused current and potential neuronal pathways, and an overall shrinking of the brain.

LEARN MORE: How the Brain Changes With Age

LEARN MORE: Ageing and the brain

LEARN MORE: Aging and Neuronal Vulnerability

LEARN MORE: Neuronal Cells Rearrangement During Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease

LEARN MORE: Changes That Occur to the Aging Brain: What Happens When We Get Older

Yet there is good news! Plasticity may be restored by motivation – if you really want to do something, and an idea excites and engages you, and you get the opportunity to follow your own interests – your brain is more amenable to change. Even as adults.

“Will it make me something? Will I be something? Am I something? And the answer comes, already am, always was, and I still have time to be.”

― Anis Mojgani, Poet Laureate of Oregon

LEARN MORE: The Neuroscience of Growth Mindset and Intrinsic Motivation

LEARN MORE: The matter of motivation: Striatal resting-state connectivity is dissociable between grit and growth mindset

LEARN MORE: Role of Lifestyle in Neuroplasticity and Neurogenesis in an Aging Brain

LEARN MORE: Adult Neuroplasticity: More Than 40 Years of Research

So yes, school might make you dumb….in a sense.

The time we’re forced to waste sitting at a desk doing repetitive and vapid tasks like prepping for mandated corporate tests is limiting our potential and overall neural well-being.

LEARN MORE: When Testing Takes Over

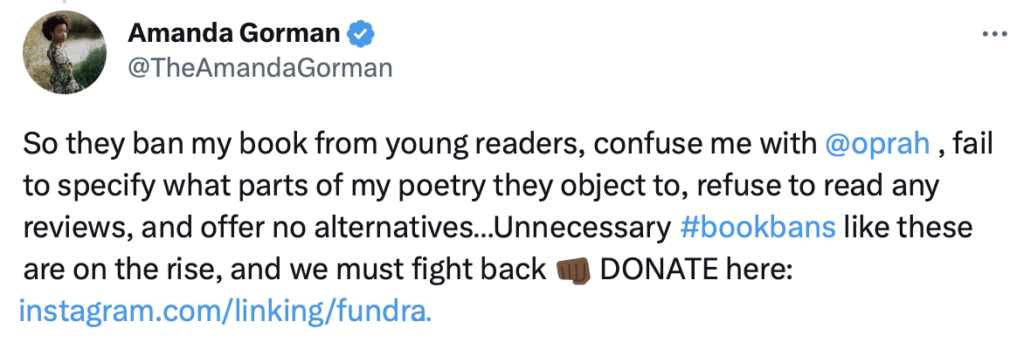

Recent efforts to drain school libraries, textbooks and educational materials of anything interesting or challenging or reflective of actual people (including Black and Native-American history, and anyone who is LGBTQAI+) will only make the experience less motivating and useful for developing brains. It may halt you from exploring your own hobbies and interests, and stop you from making art and exploring places and building those unique neuronal pathways that will make you who you are.

LEARN MORE: Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools

LEARN MORE: America has a history of banning Black studies. We can learn from that past

LEARN MORE: Florida School Bans Amanda Gorman’s Inaugural ‘The Hill We Climb’ Poem

LEARN MORE: School library book bans are seen as targeting LGBTQ content

LEARN MORE: Top 13 Most Challenged Books of 2022

Don’t get me wrong, I think education is important and necessary (if not a human right) for everyone. It’s just that the time you spend chasing A’s at school might really limit your full neuronal potential.

Be yourself, and do more of what you like. Make mistakes. Make art. Read banned books. Sculpt vases with elephants. Check out some neuroscience. And please don’t stress over grades. It’s so much better for your brain.