Post by Julian Rodriguez, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University. Julian is a welcome, regular contributor to outreach through NW Noggin, and is currently seeking grants to support arts integration in STEM.

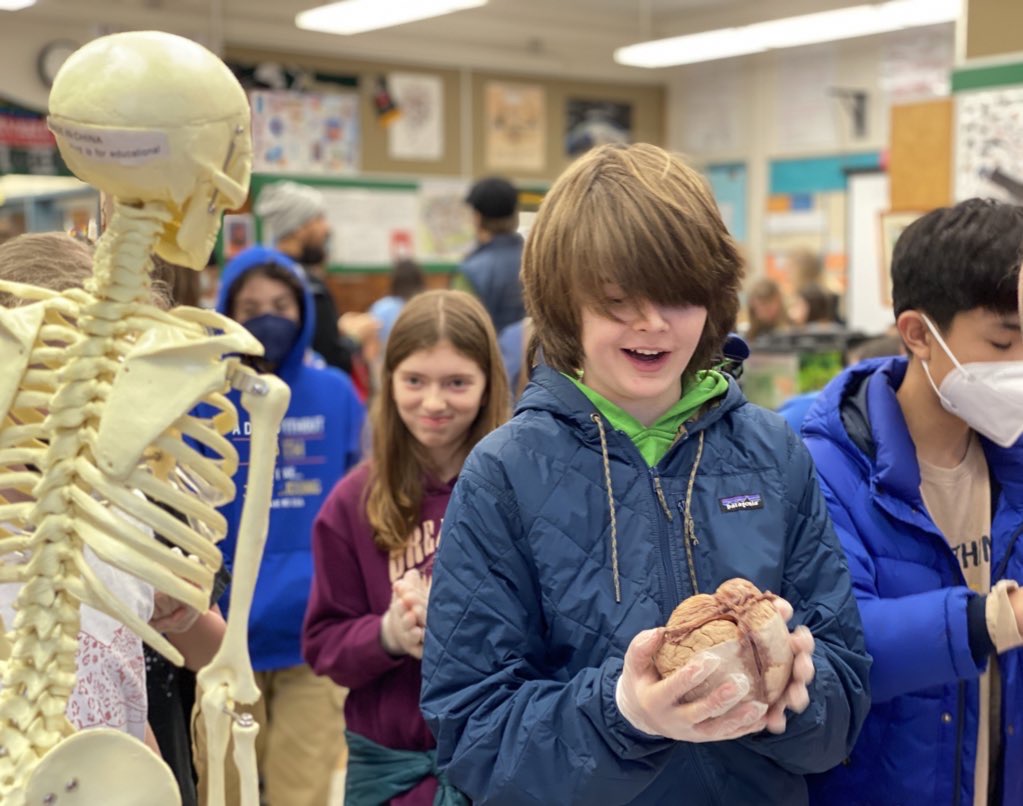

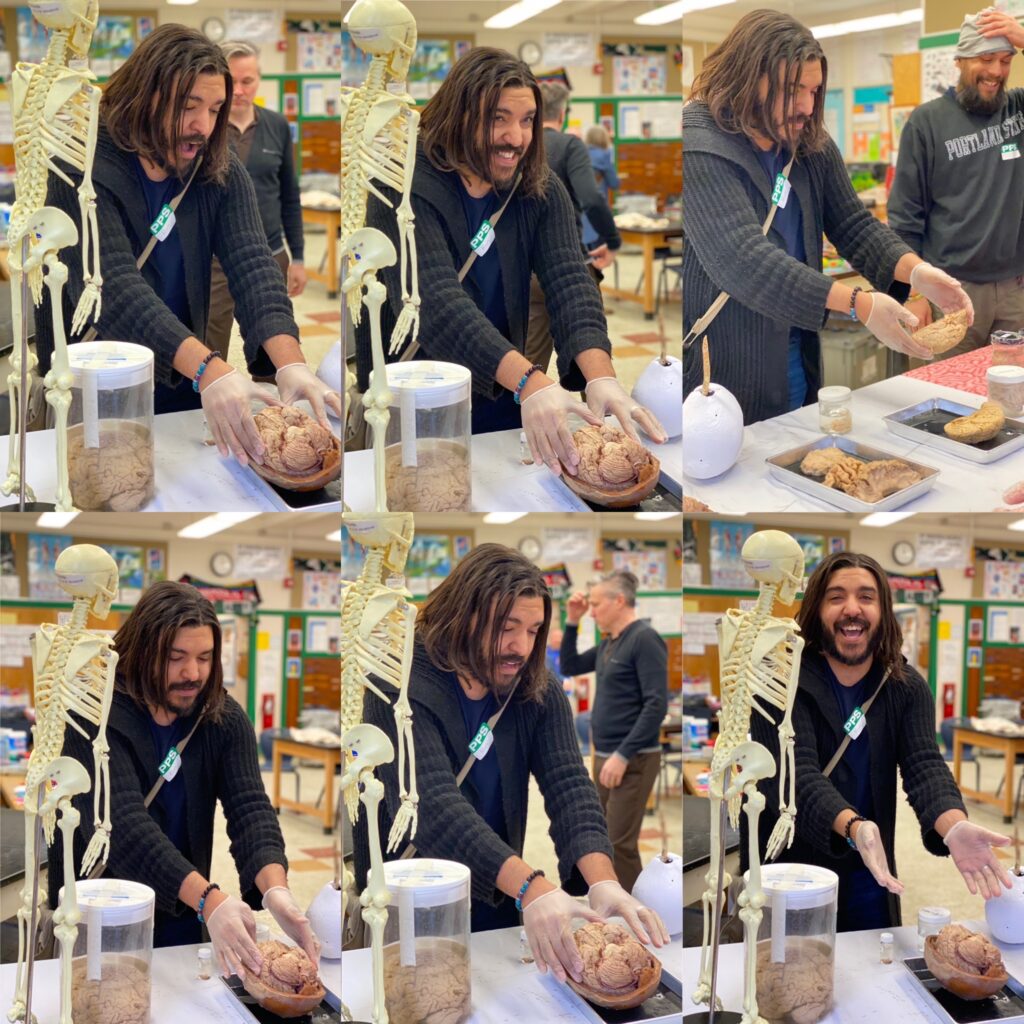

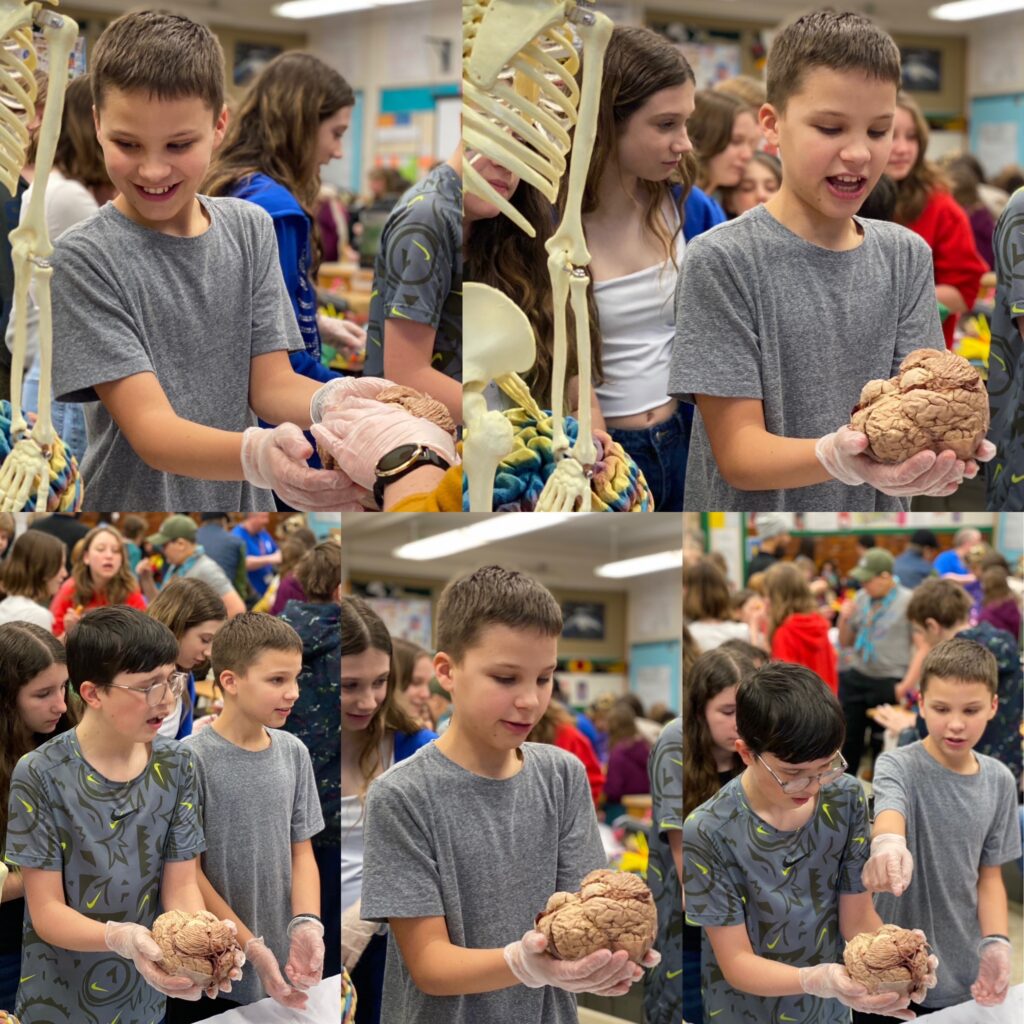

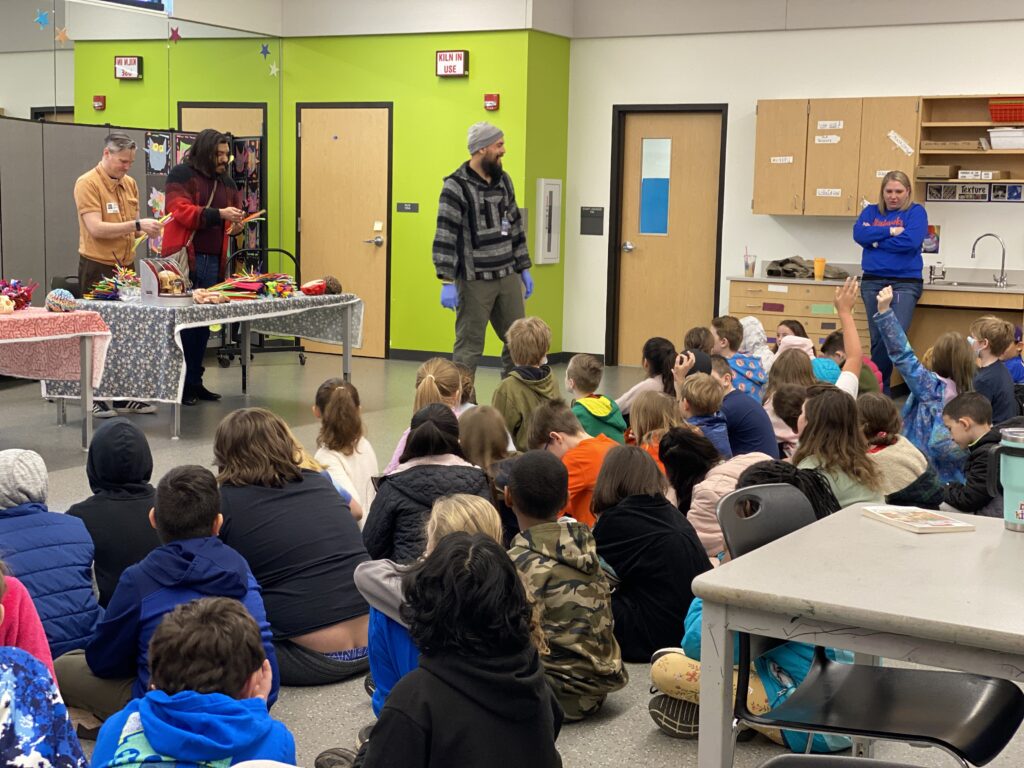

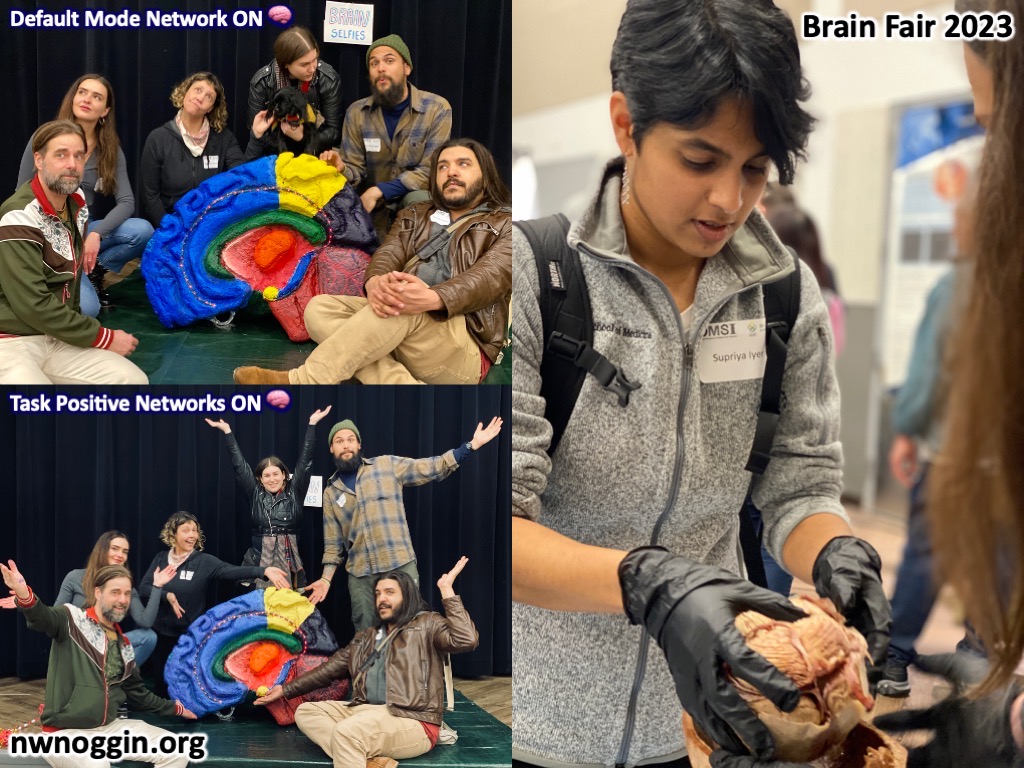

When we arrive in K-12 classrooms in the Pacific Northwest with our real human noggins we pretty much immediately get students’ attention regardless of the grade level. Some are a bit shocked, many seem jaw-droppingly awed while others are clearly at least a little grossed out!

The first questions we usually hear is: “Are those real brains?”

After all, our entire world sits in this three-pound cluster of cells. But inevitably, inquiry moves away from the palpable physicality of the brain, and we begin delving into the brain’s activities. The questions start flying, particularly in lower grade levels: “How many neurons are in a dinosaur brain?” “Is there still information in the brain when people die?” “What are dreams about?”

It is always amazing to witness students come alive when they realize that they can ask any question that comes to mind, and the discussion will genuinely value their ideas and center on exploring their interests.

LEARN MORE: How many neurons are in a dinosaur brain?

LEARN MORE: BioGifting brains

LEARN MORE: Noggin Bloggin

How can I stay calm?

At one of our outreach events a high school athlete asked me a question about staying calm during her competition. Wrestlers have multiple matches in a day and have to recover from a loss quickly before the next match. I found this topic interesting because there is a thin line between excitement and fear, and remaining in a positive mental state can make all the difference.

Mental states are moment-by-moment cognitions, emotions, and perceptions of ourselves and our physical world. Mental states can last for moments, days, or sometimes even longer but are not permanent. For instance, we all know someone who disagrees with everything. That is considered a more stable trait and will likely only change over a considerable amount of time. When you experience regret, however, it is (usually) only temporary. Regret is a mental state.

Mental states are not traits, but the two have some overlap. For instance, a person can have both trait happiness and a mental state of happiness. Think of traits like climate and mental states like weather. A cold place can get hot for a limited amount of time. A wet area can dry out, but rain is not too far out (we know that well in Northwest winters). Furthermore, our expectations influence our mental states and our perceptions of the world as we move through it. Phenomena like the placebo effect and confirmation bias are examples of how our expectations affect our experience.

LEARN MORE: The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health

LEARN MORE: Confidence drives a neural confirmation bias

Our mental state also affects our brains and bodies, and learning how to move from a negative to a positive state may impact not only your athletic endeavors but your daily life. As a competitor, the last thing you need is to have an opponent recognize your negative mental state based on how you’re presenting physically.

“Life is like a wrestling match: a lot of times, things are looking good, and then something happens, and you’re fighting from underneath.”

— Matt Hardy

What I find really fascinating is that research suggests that we incorporate the perceived mental states of others into our own representation of them, and it influences how we interact and respond.

LEARN MORE: The brain represents people as the mental states they habitually experience

Most athletes and coaches study their opponents to find physical or technical weaknesses. This study provides evidence that our representation of another person reflects how we perceive their mental state. For instance, if every time an athlete loses, they tend to drop their head, then you know that means they feel internally sad or upset. Or if every time an athlete wins, they give praise to a personal deity, then you know that they are grateful. The point is that studying these “habitual mental states” gives you an edge over your opponent – or your opponent over you.

There is evidence that we can control our future mental states through something called inoculation theory. Much like many immunizations, inoculation theory relies on you thinking ahead about what stimuli in the external environment might cause a change in your internal mental state. The idea is that you mentally go to that place, and those stimuli, to practice shifting in and out of mental states.

LEARN MORE: Re-Thinking Anxiety: Using Inoculation Messages to Reduce and Reinterpret Public Speaking Fears

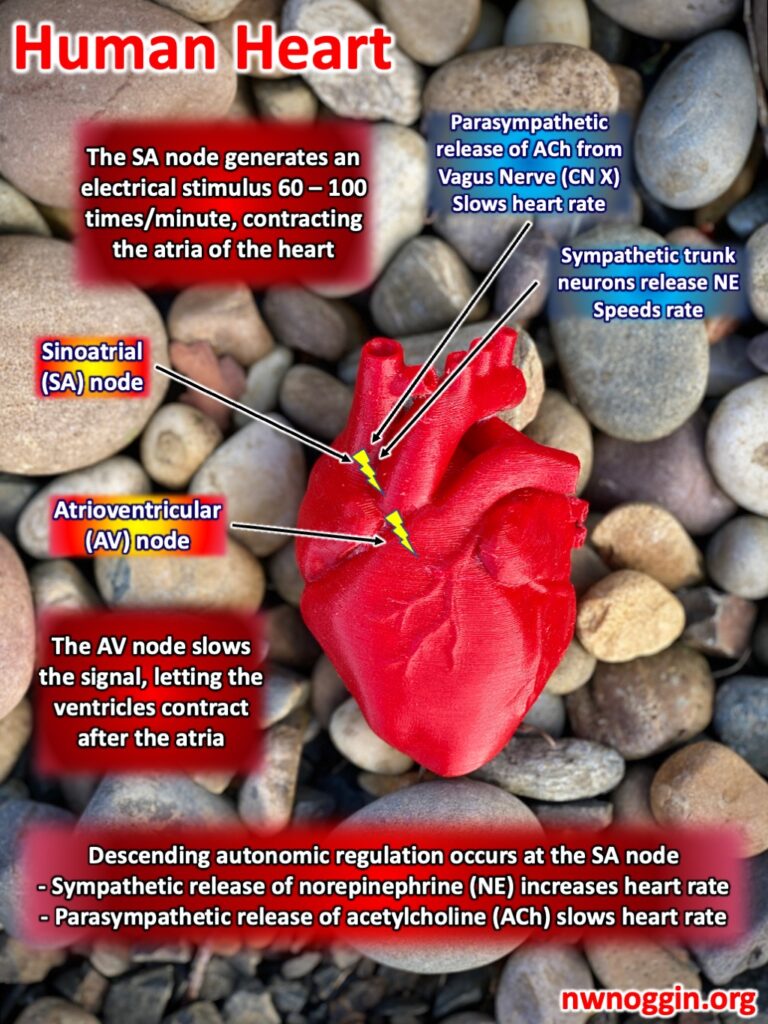

Think of as many examples as possible that will remove you from your preferable mental state. A good example that most people can relate to is public speaking. Public speaking typically makes most people nervous. What you could do before you speak is to slow your breathing, and provide reasons why those examples will not remove you from a good mental state. Deep breathing before public speaking would elevate output from the parasympathetic division of your autonomic nervous system, balancing your sympathetic fight or flight response and help naturally calm you down.

LEARN MORE: Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults

LEARN MORE: The Autonomic Nervous System

The impact of cultural traditions and beliefs

If you are a wrestler who believes that you will win a match, but you know that you always get anxious five minutes before your match, then you could find ways to steer your mind out of an anxious state and into a more relaxed state. How do you ask? Well, how about good old superstitions?

A study of high-level golfers showed that superstitions, or pre-performance rituals, get their power from allowing those who practice and become familiar with them to more easily relax. Traditions also improve peak performance in athletes by affecting their working memory, making it harder for them to focus all their attention and rumination on the obstacles in front of them.

LEARN MORE: Where’s the Emotion? How Sport Psychology Can Inform Research on Emotion

LEARN MORE: The impact of mixed emotions on judgements: a study during the FIFA world cup

LEARN MORE: I’m going to fail! Acute cognitive performance anxiety impairs WM performance

Regulating our emotions is a challenging task

And of course, none of this is easy! To begin with, honesty is essential.

When heading to do something that might change your emotional state, prepare for it. This requires knowing yourself and at least something about the situation you are heading into. Also try to stay consciously present in the moment and control your breathing. Shallow breathing is never a good idea, especially in high-stress situations. Long deep breaths are what you are looking for. Finally, if something, or someone, does throw you off, return to your breath and don’t keep reliving that moment. Once it happened, it was officially in the past. Come back to the here and now.

“My advice to young wrestlers is that your surroundings really make a difference. You want to put yourself in good, positive surroundings.”

— Dan Gable

Finally, shifting your mental state is a skill that requires constant practice and maintenance. I encourage you to practice shifting mental states like anything you want to get good at.

LEARN MORE: The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation Development: Implications for Education

LEARN MORE: From Surviving to Thriving: The Emerging Science of Emotion Regulation Training

LEARN MORE: Toward a Personalized Science of Emotion Regulation

LEARN MORE: The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress

Relieving the stress of driving

I like to practice shifting my own mental state when behind the wheel of a car.

For me, road rage was a mental state that I (unfortunately!) frequented for years. Now that I recognize driving as a mental state shifter, I employ rituals before, during, and after driving to better keep my cool.

Before I drive, I check in with myself to see where I am emotionally. If needed, I’ll take five minutes to do deep breathing or some progressive muscle relaxation. While driving, I play music or listen to podcasts, which wind me down, not ramp me up. If I find myself getting worked up by someone who doesn’t understand speed limits, turn signals, or crosswalk signs, I look for humor in the situation.

Humor is a great mechanism to combat negative emotions.

LEARN MORE: Laughter therapy: A humor-induced hormonal intervention to reduce stress and anxiety

LEARN MORE: Effectiveness of a Humor-Based Training for Reducing Employees’ Distress

Worrying about something that has already happened is as detrimental to our mental state as worrying about something that may never happen. We can bring our attention to our mental state at any moment. The best thing anyone can do, including athletes, when they feel sad about the past or fearful of the future is to find their breath. Focus on it. Control it. Slow it down.

Everyone is different of course. But whether you are a high school athlete, an educator, or a parent looking to console a child struggling with emotional regulation, we can all explore and develop evidence-based ways of moving past a negative emotional state.

LEARN MORE: Thinking too much: rumination and psychopathology

Find yourself in time and space, and breathe.