Post by Savanah Gipson, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing a minor in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience and in Biology at Portland State University. Savanah has been working in Dr. Tori Crain’s RESET lab at PSU.

When you hear the words “scientific research”, what image comes to mind? Smoking test tubes, squeaking rats, whirring machines, and unending lists of complicated numbers? I think of how science was presented to me growing up as something tangible and solid, something that produced “hard facts”, performed wondrous feats, and stood unchanging in the face of an ever-changing human populus. It was foreign and daunting and magical, and I wanted in. When I was ten, my chance arrived, and before I knew it I had a colony of 20 fuzzy agar plates, which, by the way, were growing an obscene amount of bacteria considering the cultures were swabbed from our supposedly clean kitchen counters, stashed in my parents’ fine china cabinet. This was my project for the county science fair, and while I might not have known what an experiment was before this point in my life, my desire to continue experimenting after the fact was something that never left.

Many years later, I can say that ten year old me would be proud of how far I’ve come in our investigative journey, and a lot of the aspects of science that I loved, like test-tubes and weird lab-grown monstrosities, I still love today.

However, as I think back on how I used to view the world, I realize that my understanding of science as a practice has shifted to be something entirely different and much less objective. I used to think that there was no room in science for personal experience, or anything that veered away from cold, hard numbers. What I know now is that science is a process, one that we perform unto things we wish to understand and one that will ultimately be influenced by every person involved. This process does not result in the discovery of immovable, unchangeable fact, but instead a dynamic story that grows and develops with each new piece of information we gain. Most importantly, the products of the scientific process cannot be complete without taking into account how we, as humans, interact with, perceive, and influence these stories, something that can only be found by studying subjective experience.

LEARN MORE: The Value in Science-Art Partnerships for Science Education and Science Communication

But how did I get here, and what made me change? Well, it all started earlier this year when I finally got the chance to take Research Methods in Psychology as part of my Psychology degree at Portland State University.

Finding My Research Interest

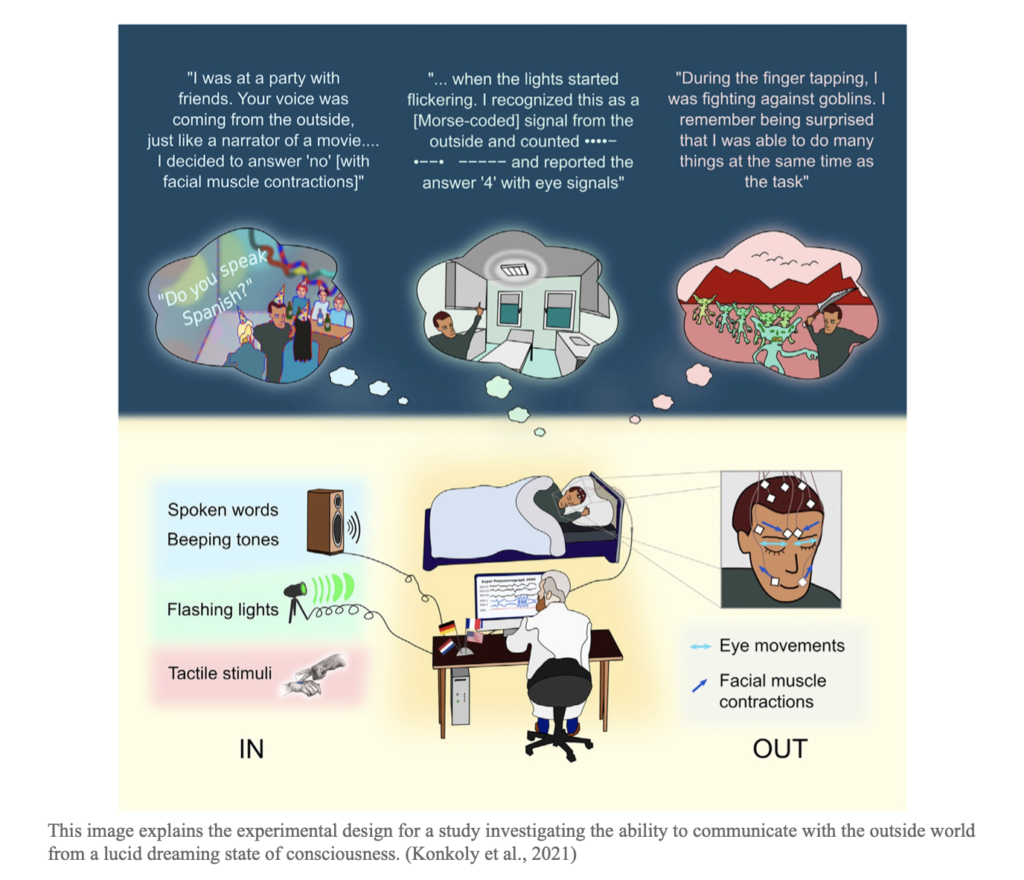

After years of studying, and waiting, and studying some more, I finally got my first taste of “real” research in January of this year. I was taking Research Methods in Psychology and was elated to learn that the term would be spent developing individual research proposals for a project of our choice and design. While my 8th grade fantasy of cheetah-hummingbird hybrids and anti-aging space-traveling cryo chambers had taken a back seat long ago, I was a psychology student now after all, I had something equally as exciting in mind: lucid dream induction, a topic of much personal interest and one that could open the doorway for the proposed psychotherapeutic applications of lucid dreams. I wanted to know why I lacked lucid dreams, the psychological mechanisms behind them, and the most reliable induction techniques that had been created to date. Most of all, I wanted to devise an induction technique that was properly suited for clinical use.

LEARN MORE: Lucid Dreaming To Treat Nightmares

LEARN MORE: Consciousness While Lucid Dreaming

By the end of winter quarter, and a long review of the lucid dreaming literature, I had found lucid dream induction to be an elusive and mysterious process that seemed to avoid any proper decoding, despite the efforts of numerous qualified scientists. That’s not to say that the field lacked progress (click here for one of my favorite LD studies), but results were often far from conclusive and there was less solidified knowledge on the subject than I had expected (click here for a meta-analysis of published LD studies). The efficacy of induction techniques varied greatly between studies, and none of them had worked out a method of predictable induction. Sure, doing this or that technique may increase the odds of you experiencing a lucid dream, but the odds were still low, and there was little consistency with when the lucid dream would occur relative to when the technique was performed. As you can imagine, this was not the best case scenario for a potential clinical treatment. In the end, I worked with the available information and completed my project, but I just wasn’t satisfied.

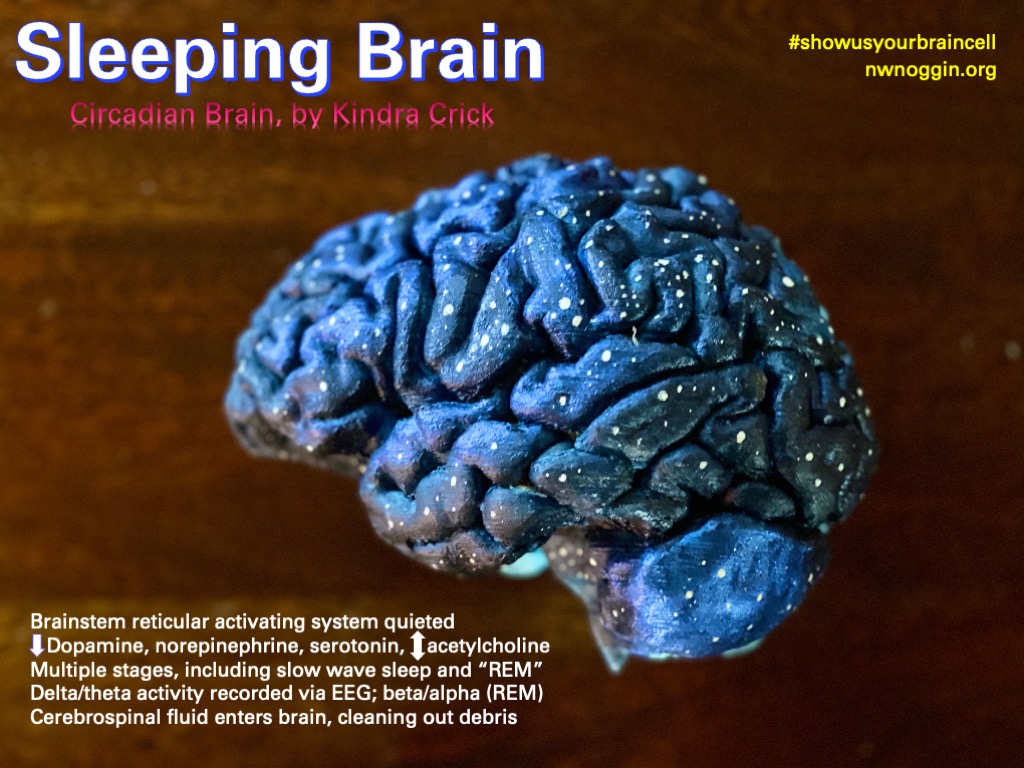

From all of the studies I had read, it was starting to seem like this dearth of lucid dreaming science was the symptom of a larger issue, a deeper, underlying mystery of which lucid dreaming was just a sub-sub-subcategory: the psychology of sleep.

LEARN MORE: The cognitive neuroscience of lucid dreaming

LEARN MORE: Is It a Good Idea to Cultivate Lucid Dreaming?

LEARN MORE: Lucid Dreaming: A State of Consciousness with Features of Both Waking and Non-Lucid Dreaming

LEARN MORE: Findings From the International Lucid Dream Induction Study

LEARN MORE: Lucid dreaming increased during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey

LEARN MORE: My Dream, My Rules: Can Lucid Dreaming Treat Nightmares?

The Next Step

While I had been interested in sleep for some time prior (imagine me skipping around, knee deep, in a lake that metaphorically represents sleep science), this project brought that interest to a whole new level (now imagine me flying off a diving board, hitting the water with a resounding splash, and sinking so deep that I actually turn into a fish so I never have to come up for air again). I knew that I wanted to pursue this professionally, and that I needed hands-on experience. My professor for the course, Liana Bernard, was happy to help me put together a CV and find research labs that would allow me to explore my interest in the topic. Two months later, I was accepted into Dr. Tori Crain’s research lab at Portland State University as an undergraduate volunteer research assistant.

What the Lab Does

The Researching Employee Sleep, Equity, and Time for family (RESET) Lab, is a research lab at Portland State University run by Dr. Tori Crain that specializes in Industrial-Organizational (I-O) psychology, a branch of study focused on the psychological aspects of running a workplace, serving in a workplace, and the effects that an employee and their work can have on each other, and Occupational Health Psychology (OHP), another related area focused on protecting the health and well-being of employees. There are a multitude of projects going on in the lab, many of which are run by a brilliant and passionate cohort of graduate students, each with their own specialized interest in I/O. The topics of study range from not only employee sleep and fatigue, but also employee stress and health, diversity & inclusion, work-life balance, resignation, leadership in the workplace , and so many more!

Every person sleeps, and so every person is impacted by the process of sleep. Because of this, the study of sleep and its effect on a person’s psychology are relevant to virtually all of the topics mentioned above, and procedures measuring variables of sleep can be found across many different studies in the lab. I was excited to be working at a place that approached sleep in so many different ways for so many different subtopics within I/O Psychology.

LEARN MORE: Researching Employee Sleep, Equity, and Time for family @ PSU

LEARN MORE: RESET Lab Publications

LEARN MORE: RESET Lab Science Outreach

An Objective Bias

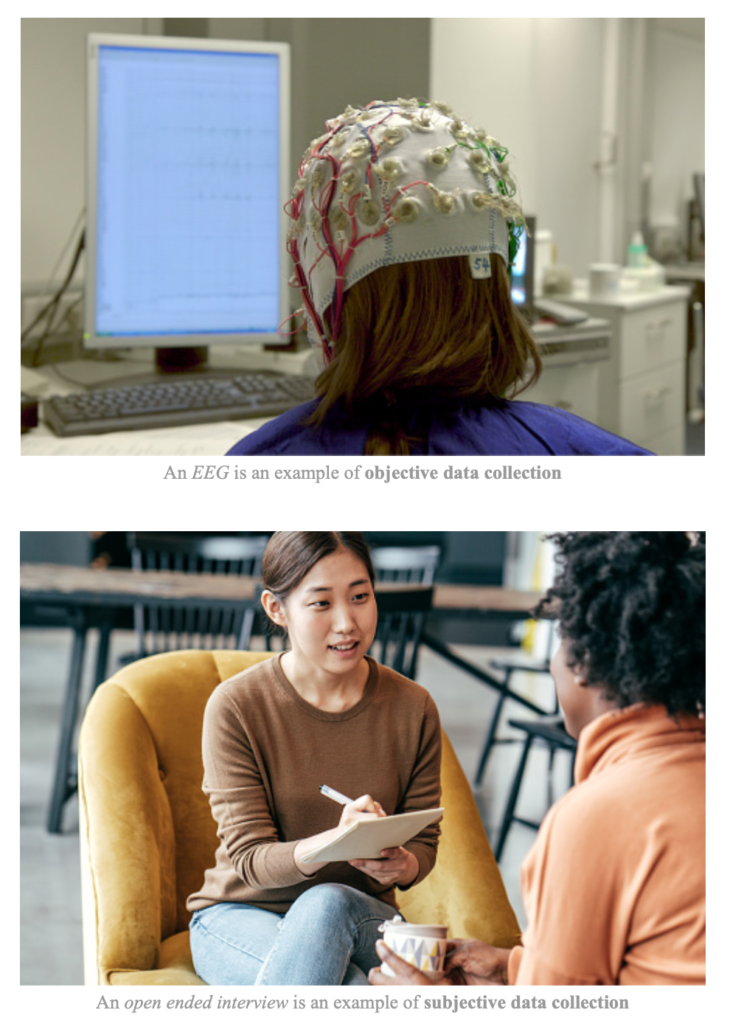

Up until my time at the RESET Lab, I had only ever worked with objective data. As a student in the sciences, objective data had always been presented to me as the better of two options, subjective data coming in second place. Numbers, “facts”, specifically calculated measures, they were more scientific, I was told, more reliable, and therefore more relevant and impressive than the typical subjective measure. As a student new to the research game and early on in their academic career, I have to admit that I was eager to prove myself as a real scientist. Psychology is a field that’s already often discredited as not truly scientific, and so I tried to make up for this by focusing exclusively on numbers, only wanting experience with quantitative studies.

So then I joined a lab with many extensive . . . subjective studies? Wait, did something get lost in translation? What happened to the numbers, my sweet, sweet gold star of scientific validity?

It turns out that when it comes down to studying sleep or gaining strictly objective research experience, I would choose sleep a thousand times over. So on to the subjective data it was.

What’s the Difference Between Objective and Subjective Data?

Objective data is measured and observed through means that are separate from someone’s personal interpretation of an event or experience and is thought to more accurately reflect what is actually happening, while subjective data is measured by recording a person’s perception of an event or experience. For example, if a study was investigating what emotions certain pictures triggered within participants upon viewing, an objective measure could involve recording participants’ brain activity when exposed to the pictures, and a subjective measure could involve asking participants to describe how they feel upon viewing the picture. Common methods of collecting subjective data are surveys and interviews, where respondents provide the answers to questions about themselves or their perceptions.

My Introduction to Subjective Data: Coding

My first experience handling subjective data was working on qualitative coding, a form of data analysis, for a series of interviews investigating leadership styles. In order to do this, I had to first learn the basics of interview coding, learn the definitions for the codes provided to me by the lead researchers, and then label the sections of the interviews that I felt matched up with one or more of the codes.

Qualitative coding is a method through which unquantifiable information, such as an interview transcript or a series of natural observations, can be transformed into analyzable data. Once the information has been gathered, researchers go over the transcripts and begin to identify common themes, behaviors, or words that appear across the study. These can then be grouped under or assigned a specific code, which is oftentimes a word or phrase. Once a list of codes has been drafted up, the information collected from the participants will be fully reviewed and the occurrences of each code will be labeled and counted. The analysis of the resulting data can provide fascinating insights into the relationships between codes, like how frequently they occur compared to other codes, differences in when these codes occur, and the context in which they occur, as well as the relationships between codes and demographic information of the participants.

LEARN MORE: Coding in Psychology

Intercoder Reliability

Because the researchers themselves are defining the codes based on their own interpretation of the interview, it’s important to check that the code definitions (what theme/behavior fits under the code) and the identification of such codes when reviewing the transcripts are similar across all researchers involved in the coding. Differences among the researchers can signal that the theme/behavior associated with a code is not occuring enough to warrant a code, the code definitions are unclear, or that personal bias is influencing the identification of codes, despite clear definitions. All of these issues can lead to skewed data and inaccurate conclusions. One way to check intercoder reliability, and the way that I helped, is by bringing in researchers that were not involved in defining the codes to perform coding on a handful of interviews. These results can then be compared to the results of the lead researchers to see whether the codes were interpreted similarly and identified as frequently when handled from an outside perspective.

Data Tells a Story

When I started coding these interviews to provide a set of comparison data for intercoder reliability, I found myself blown away by the range of information present. Each participant interview was different, and yet also showed an interwoven pattern of feelings, opinions, topics, and behaviors. From reading just one interview alone, I felt like I was getting more of a complete story than I had in the past with entire sets of objective data and numbers. This subjective data was providing something for me that objective data wasn’t: a connection to the lived, human experience of the participants. I wasn’t deducing how they were feeling from external, rigid measurements. Instead, I was hearing straight from the source how certain situations had impacted their lives, how their perceptions had influenced the situations around them, and how the things they had lived through had impacted their perceptions. It was like I could feel the shift happening in my brain as I made my way through the interviews. This data was equally as important, and I was seeing for myself firsthand, through the process of coding, that it could be analyzed just as rigorously and scientifically as well. Humans are subjective beings, no matter how hard we may try not to be, so it would only make sense that in order to understand human psychological phenomena, we would need to be investigating and analyzing our subjective experiences. I realized that, at the end of the day, what matters to me most and what shapes my quality of life, psychologically speaking, is how I am processing, interpreting, and experiencing the world around me, so why wouldn’t I think that subjective information was important for understanding and improving the way others function psychologically? I knew, moving forward, that this was something I needed to heavily consider when beginning my research on sleep.

Measures of Sleep: Applying What I Had Learned

The Undergraduate Research Symposium

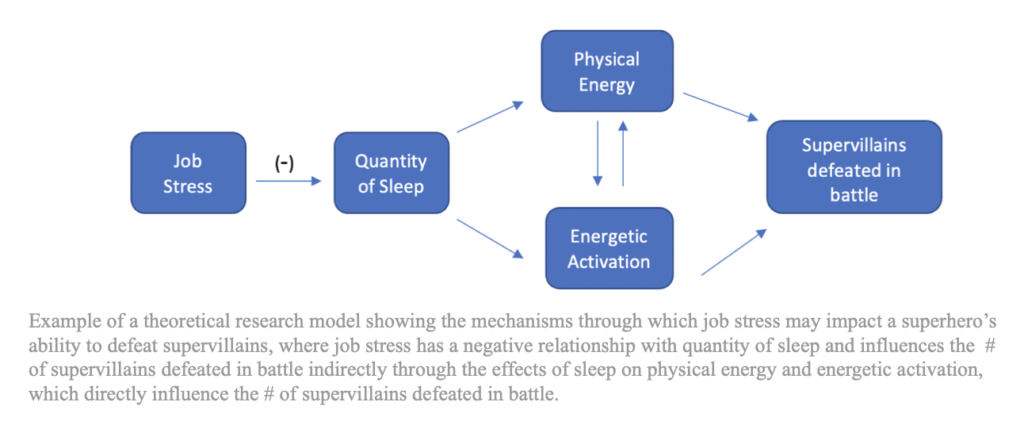

One of the personal projects I got to work on through the lab, was my proposal for PSU’s Undergraduate Research Symposium. My subject of study was going to be sleep, but in order to put together a cohesive proposal, I was going to be working with some data sets that had already been collected for past studies. As the first step in this process, I started by looking through the codebooks for the past studies with available data. Codebooks are documents which explain the purpose of the study, all of the measures that would be used and what variables they would collect, information on how many times each variable was collected, and also demographic information on the sample of participants used in the study. From this information, I could come up with intervariable relationships that I wanted to look into, and create some flow diagrams to exemplify how I predicted they would interact.

Sleep & I/O Psychology

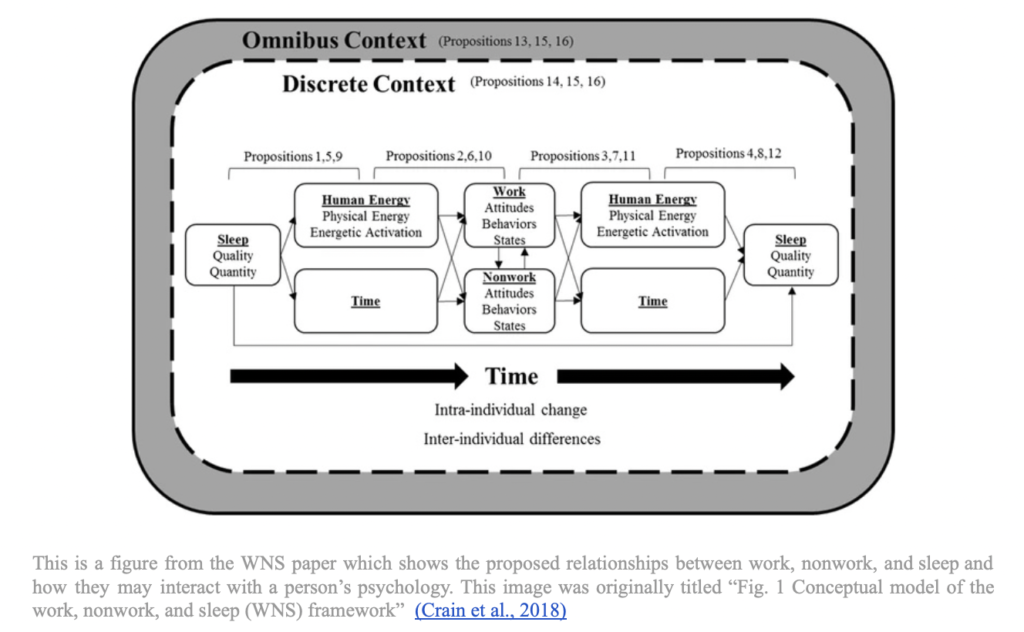

While I had studied some aspects of sleep psychology in the past (throwback to my journey with lucid dream induction!), the codebooks I was working with were looking at sleep specifically as it functioned within I-O psychology, so my next step was to understand how sleep was typically approached and studied as a variable within this specific field. One of the first articles I started with was on the work, nonwork, sleep interface by Crain et al. (2018). Since it was written by Dr. Crain, I thought it would be a good way to gain some insight into how sleep had been approached in the RESET lab, and may help me better understand some of the lab studies I would be drawing from for my research project. The paper proposed a theoretical framework that explained how the three main aspects of an employee’s life, work, nonwork, and sleep would interact with each other and the individual to impact energy levels, moods, and psychological states.

LEARN MORE: Work, Nonwork, and Sleep (WNS): a Review and Conceptual Framework

One point of the paper that stuck out to me was that sleep quality and sleep quantity, two variables which reflect the characteristics of someone’s sleep, are often approached as the same and used interchangeably, despite the fact that they measure two completely different things.

Sleep quantity measures the numerical amount of sleep that someone receives (1 hour, 3 hours, 8 hours etc.), while sleep quality measures aspects like how restful it was, how many times a person wakes up throughout the night, and how a person perceives their sleep experience. Sleep quality can also take into account sleep quantity, as less sleep has been associated with poor quality sleep.

Measuring Sleep

As I read more papers on sleep, I indeed noticed that quantity and quality were often only lightly distinguished from one another. Furthermore, I noticed that the measures used to ascertain sleep quality and quantity were often very different across studies. Some studies used subjective measures for both sleep quality and quantity. For example, asking a participant to report how many hours they think they slept (quantity), or asking a participant how rested they felt upon waking up (quality). Some studies used only objective measures to ascertain sleep quality and quantity. For example, they may use actigraphy data from wristwatch-like devices to deduce the number of hours slept in a night (quantity), and they may use occurrences of sleep apnea and awakenings throughout the night to deduce how restful it was (quality). Then there were studies that used subjective data for one variable and objective data for the other. This discrepancy between studies made it even harder to tell the effects of sleep quality and sleep quantity apart, as different measures can often produce different results.

A Combined Approach

Moving forward with my project, I hope to compare how sleep quality and sleep quantity interact with other variables. However, because of the difference in data collection between studies, I think it’s only fitting to explore these interactions with both the subjective and objective data available on sleep. I’m hoping that this will shed some light on the possible differences between the effects of sleep quality and sleep quantity on a person’s waking psychological state, and whether or not these differences are influenced by the type of data collected (subjective vs objective).

Subjective Science: A New Point of View

Through my time with the RESET Lab and my subsequent exploration of subjective data, my approach to the practice of science has shifted. I feel like the reason we practice science in psychology is to ascertain how we interact with and are influenced by the environment, the people around us, and even ourselves. While objective data can certainly help inform us of how things are going down, our experience of these things will always be subjective. Without the bigger picture that subjective data can provide, it can be hard to understand the full scope and psychological implications that a study or phenomenon may have. There is a place in science, a need in science, for the stories and experiences of those being studied, and the subjective data that can provide this information is a crucial piece to the scientific puzzle.

More on the RESET Lab

Before I go, I would like to tell you a little bit more about how my time at the RESET Lab has gone so far…

Working in the RESET lab has been an incredibly interesting and educational experience. I feel like all of the team members’ backgrounds in I/O psychology have provided them with a true understanding of employee health, workplace dynamics, and work-life balance, which has resulted in a supportive and uplifting work environment. Since this was my first experience working in a research lab, I was nervous that I might not have the skills needed to meet their expectations, and I had no clue what to expect, but my passion to learn and to help wherever I could was met with an equally strong passion to teach and mentor from Dr. Crain and the graduate students.

Here are some of my favorite aspects of working in the RESET Lab

Article discussions in meetings

When we have lab meetings, there is often an article that we are alerted to read beforehand and come ready to discuss. These articles typically cover a topic relating to the practice of research within the field of I/O Psychology, and provide a great opportunity to expand my knowledge, develop as a researcher, and to learn from other members of the lab when we open the floor to share our thoughts and ideas surrounding the article.

Mentoring

Dr. Crain and the graduate students have provided me with an astounding amount of mentoring that has not only helped me develop as a researcher, but has helped me focus my interests and establish a course of action for my post-graduation plans. I plan on attending graduate school, and the lab has been incredible with helping me parse out the application process, as well as how to search for the best programs.

Human Subjects Research Training (CITI)

Since the lab works with human data, I had to complete the Human Subjects Research Training (CITI) available through Portland State University. During this training, I learned how to handle human data responsively, ethically inform participants of their role in a study, and got an overview of the research guidelines and rules for specific demographics, such as children and pregnant individuals. With this training under my belt, I am now qualified to work with human subjects across a wide variety of studies.

LEARN MORE: Human Subjects Research (HSR) CITI Program

LEARN MORE: Research Integrity & Compliance Programs @ PSU

A Multitude of Projects

One of my favorite things about the RESET lab is how many different projects I get to help out on. It’s always interesting to learn a new research method or expand my knowledge into a new subtopic of study. I’ve learned a lot about research as a whole, including how to pilot a survey, code development, transcribing audio recordings, and a lot on the process of developing a research idea from scratch. I’ve also learned a lot about I/O psychology, which was something I had very little experience with before joining the lab, like management styles, job satisfaction, job resignation, the work-nonwork interface, and so much more.

I owe much of my development as a researcher to the wonderful members of the RESET lab, and I am so grateful for their kindness, support, and willingness to teach. I anticipate continuing to work with the lab for the rest of this academic year, and I can’t wait to see how our current projects develop and what new ones will come to the table!