Post by Brittani Wallsten, undergraduate in Psychology pursuing a minor in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience at Portland State University. Brittani has been working in Dr. Barb Sorg’s lab at Legacy Research Institute.

As I’m sure many of you can relate, I am fascinated by the brain.

It’s so interesting to me that there are things can overwhelm it and use some of its mechanisms against us, specifically substances, though pretty much anything can. Substance use disorder is a major issue for our society and many individuals living within it. I wanted to find a way to contribute to the field and help folks dealing with these disorders, but I wasn’t sure where in that field I wanted to be.

LEARN MORE: Substance Use and Co-Occurring Mental Disorders

In my mind, I simplified it into a spectrum. On the one side you have research and on the other you have direct service. (This isn’t completely accurate because there is also policy work, administration, so many different populations, etc.). But I was most interested in these two areas and hoped to find my place somewhere in between them.

I’ve worked in direct service with folks living with substance use disorders and other mental illnesses for about two years, but I’d never experienced the research side for myself. So, I began looking for a way to get involved. Dr. Bill Griesar at Portland State University was kind enough to give me an introduction to a Principal Investigator (PI) at Legacy Research Institute (LRI) named Dr. Barb Sorg. She is the chair of the neurobiology department and has spent a lot of her career looking at addiction, memory, and learning in the brain. Specifically, one of her main areas of interest are perineuronal nets (PNN’s). These are special webs of molecules that wrap around certain neurons as a part of the extracellular matrix (Sorg et al., 2016). Dr. Sorg wrote a nice review paper discussing what these are and how they contribute to so many different aspects of our cognitive function and disfunction:

“Perineuronal nets (PNNs) are unique extracellular matrix structures that wrap around certain neurons in the CNS during development and control plasticity in the adult CNS. They appear to contribute to a wide range of diseases/disorders of the brain, are involved in recovery from spinal cord injury, and are altered during aging, learning and memory, and after exposure to drugs of abuse.”

— Dr. Barb Sorg, Legacy Research Institute

LEARN MORE: Casting a Wide Net: Role of Perineuronal Nets in Neural Plasticity

LEARN MORE: Perineuronal Nets: Plasticity, Protection, and Therapeutic Potential

LEARN MORE: Perineuronal Nets and Their Role in Synaptic Homeostasis

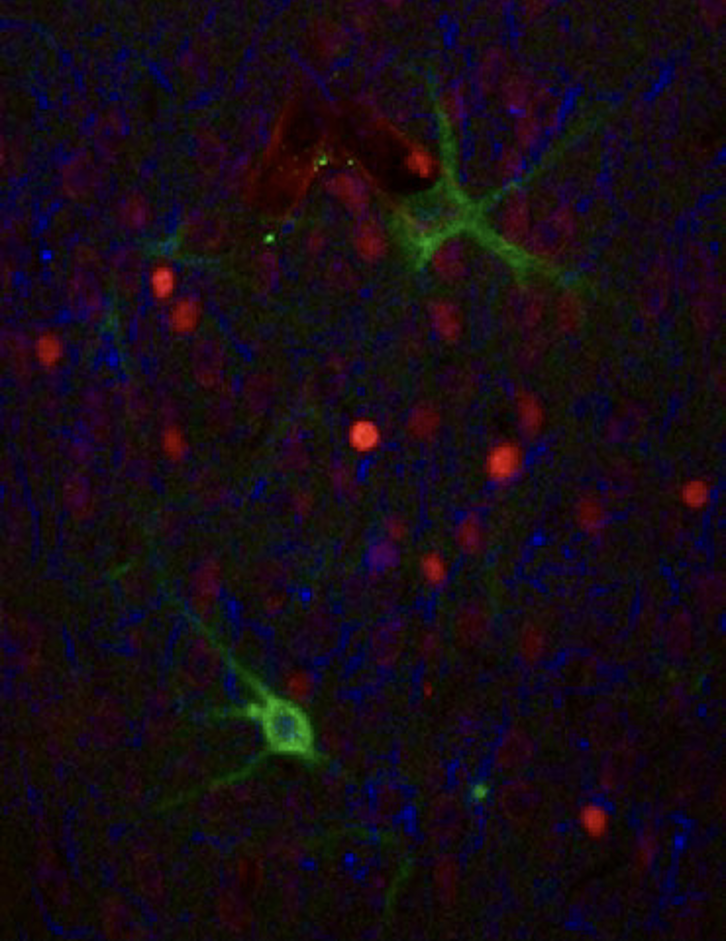

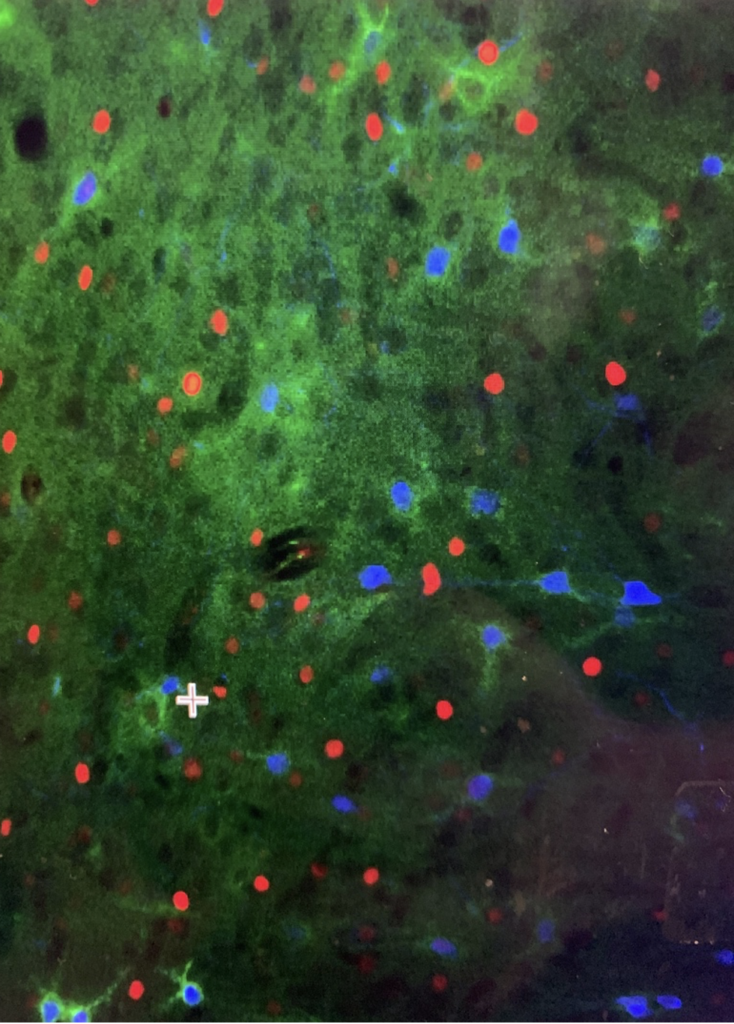

Here’s a couple of images of what perineuronal nets look like.

In these pictures we stained the nets with a green fluorescent compound. You can see that they wrap around a few neurons but not all of them. We used a red stain to show activity in the nuclei of neurons and a blue stain to mark a certain kind of neuron that often have nets. As you can see there are way more red and blue dots than green nets. In the second image (below), some of the green stain spread into the background, but you can still see bright webs around a few blue or red neurons.

These nets protect certain neurons from damage, but make it difficult for new connections to form (Sorg et al., 2016). Infants and young children have almost no nets because their brains are brand new and forming new connections all the time. Adults, on the other hand, have tons of nets which protect our neurons from damage as we age. And yet, it’s harder for new connections to form.

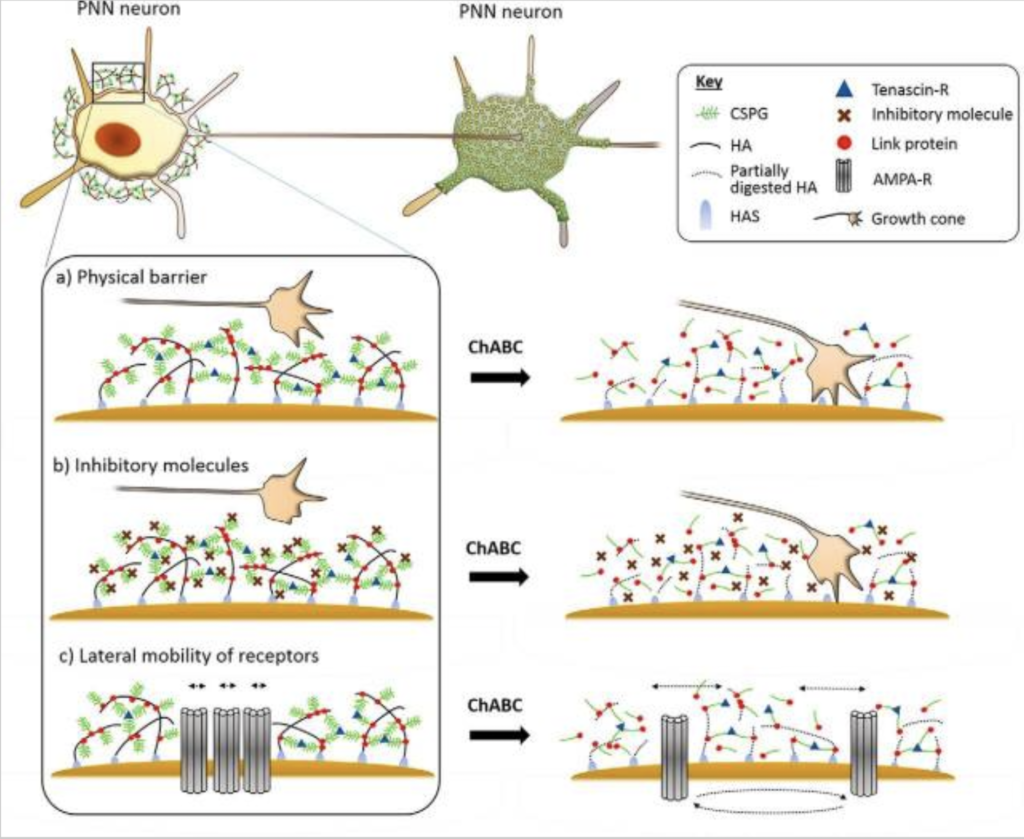

Here’s a figure from Dr. Sorg’s paper that shows how the nets keep new connections from forming.

For folks dealing with substance use disorder, these nets protect pathways that they may really want to change. So how do we disrupt these nets?

This is what my lab has been researching for awhile now. We train rats to press a lever for a small infusion of cocaine. Over time they develop something like a substance use disorder and we try different methods to reduce their pressing (i.e. their craving).

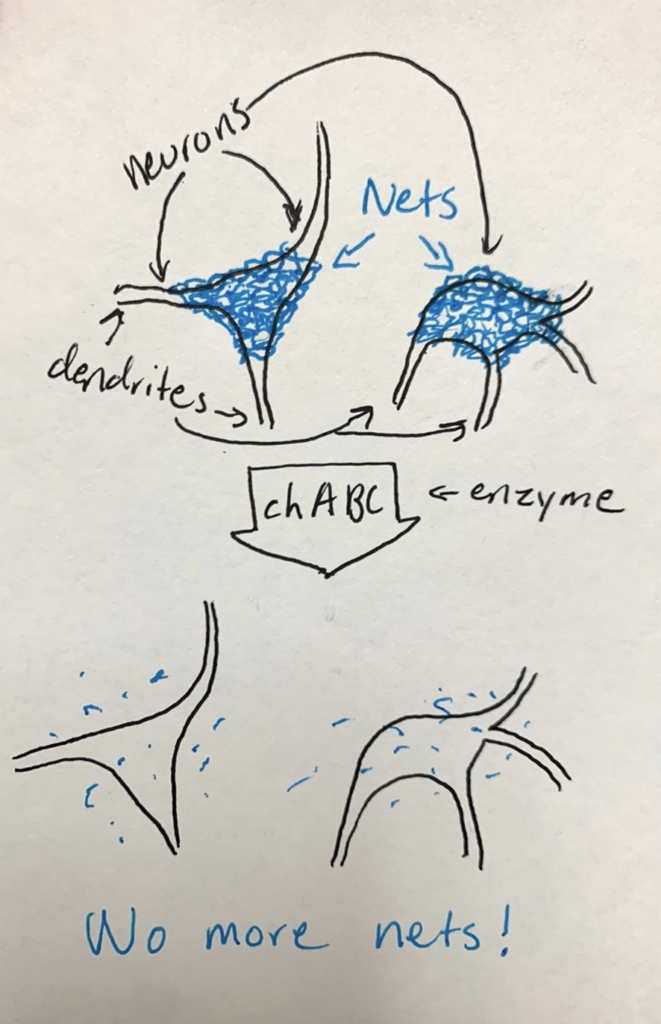

There are enzymes we can use to chew up the nets and free the cells in the rats’ prefrontal cortexes (where decision making happens), and they show far fewer lever presses after the treatment.

However, these enzymes are dangerous because they can affect other important structures as well and not cleared for use in humans. So, what can we try instead? How about something that we know improves plasticity in the brain, isn’t well understood, but is already FDA approved for treatment of mental illnesses in people?

Ketamine!

Ketamine is an interesting substance that has recently been studied and cleared for use in people as a treatment for major depressive disorder. But the mechanisms of how it works aren’t well understood at the moment.

“These results suggest that ketamine may facilitate abstinence across multiple substances of abuse and warrants broader investigation in addiction treatment.”

LEARN MORE: Efficacy of Ketamine in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review

LEARN MORE: Neurocognitive impact of ketamine treatment in major depressive disorder: A review

We’re testing ketamine to see if it works by disrupting nets. After we train our animals to press for cocaine we give them an infusion of ketamine. After its immediate affects have worn off we test the animals’ behavior to see if there’s a change. Finally, we’ll look at their brains to see if the nets look different compared to the control group.

We’re comparing doses, routes of administration, contexts, timing, and many other variables to learn as much as we can about how ketamine can affect memory and drug craving. We don’t know anything just yet, at least nothing I’m allowed to share

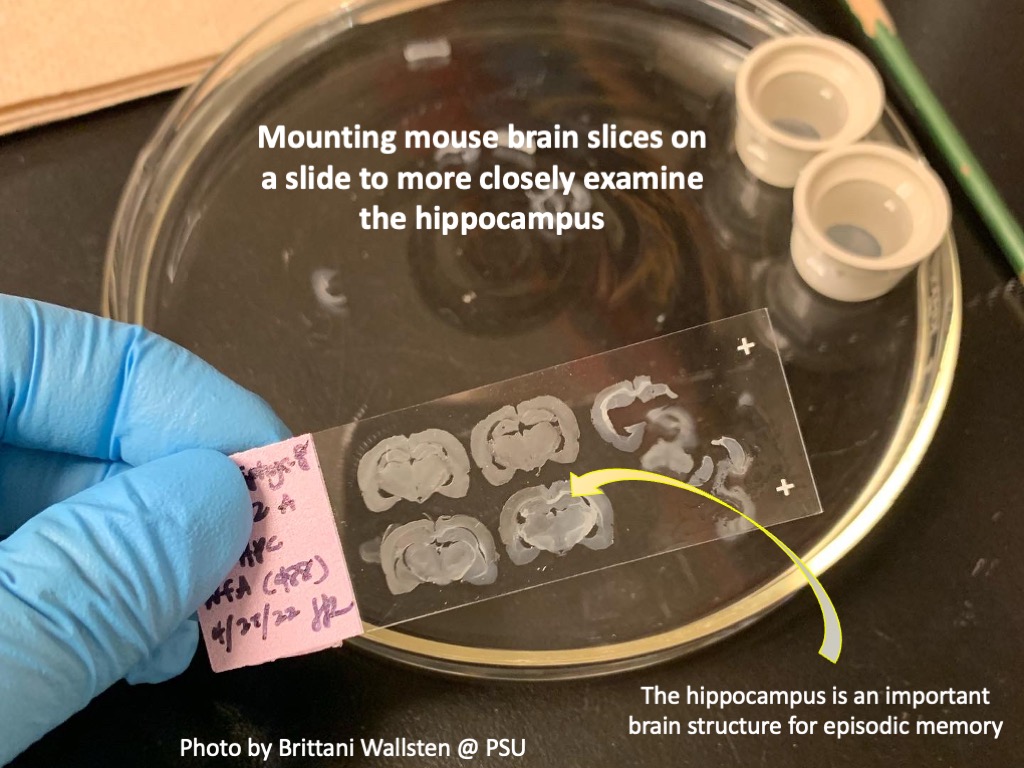

Here’s an image from one of many analysis sessions I’ve done.