We kicked off fall term with a return to p:ear, a remarkable Portland nonprofit aimed at building positive relationships with homeless and transitional youth through education, art and recreation. NW Noggin has collaborated with p:ear for SEVEN years (!), and we were honored to serve as their Community Partner of the Year in 2020.

LEARN MORE: Noggin @ p:ear

Learning about brains and behavior, and genuine, evidence-based structural and functional aspects of who we are is powerful and actionable information for everyone, including those who are experiencing anxiety, depression, drug use disorders, bias, chronic stress, insomnia – as well as poverty, isolation, racism, police brutality, homophobia and our region’s extreme lack of affordable housing.

Faces and the Brain

“Now I become myself. It’s taken

Time, many years and places;

I have been dissolved and shaken,

Worn other people’s faces,”

–May Sarton

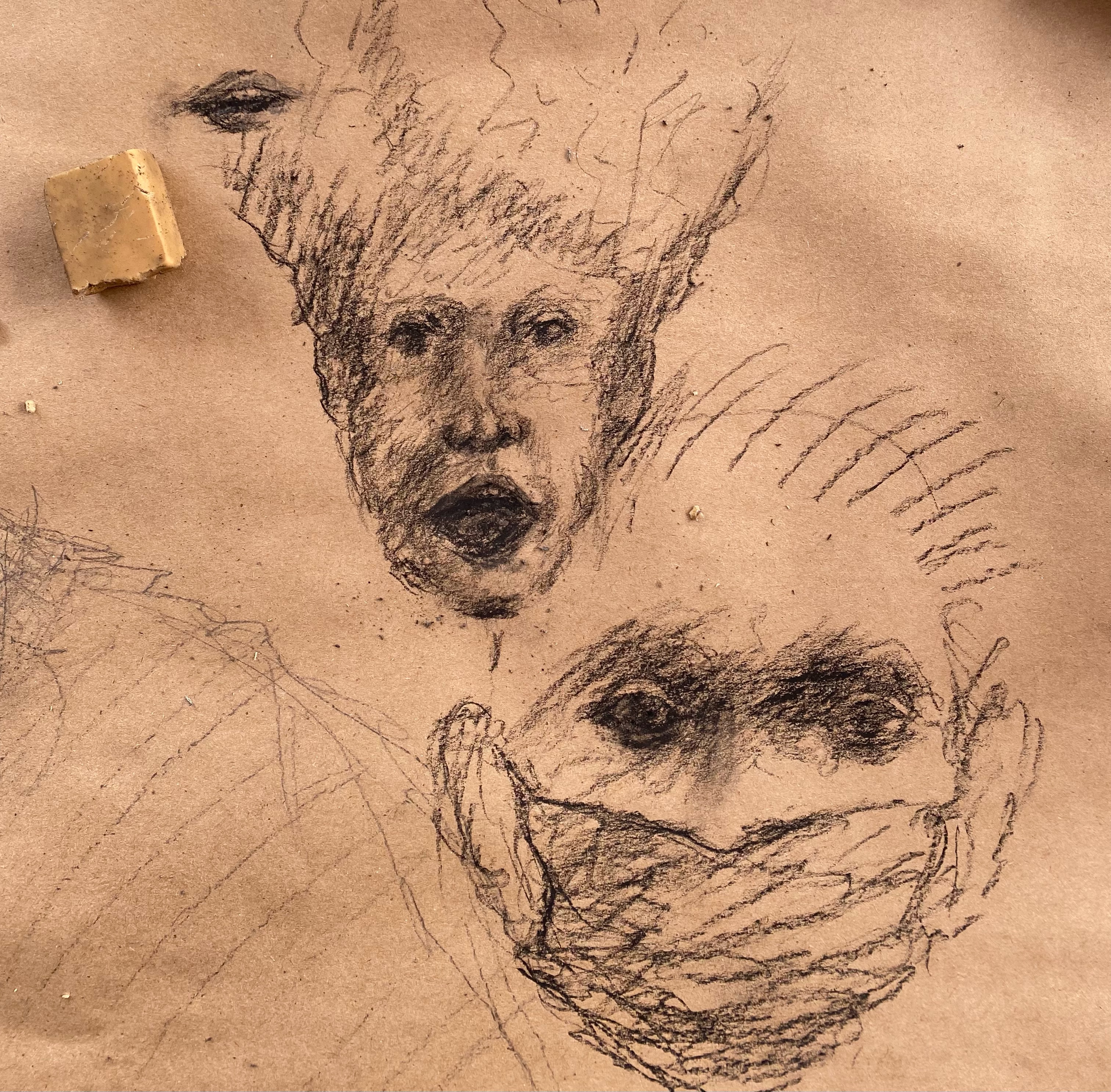

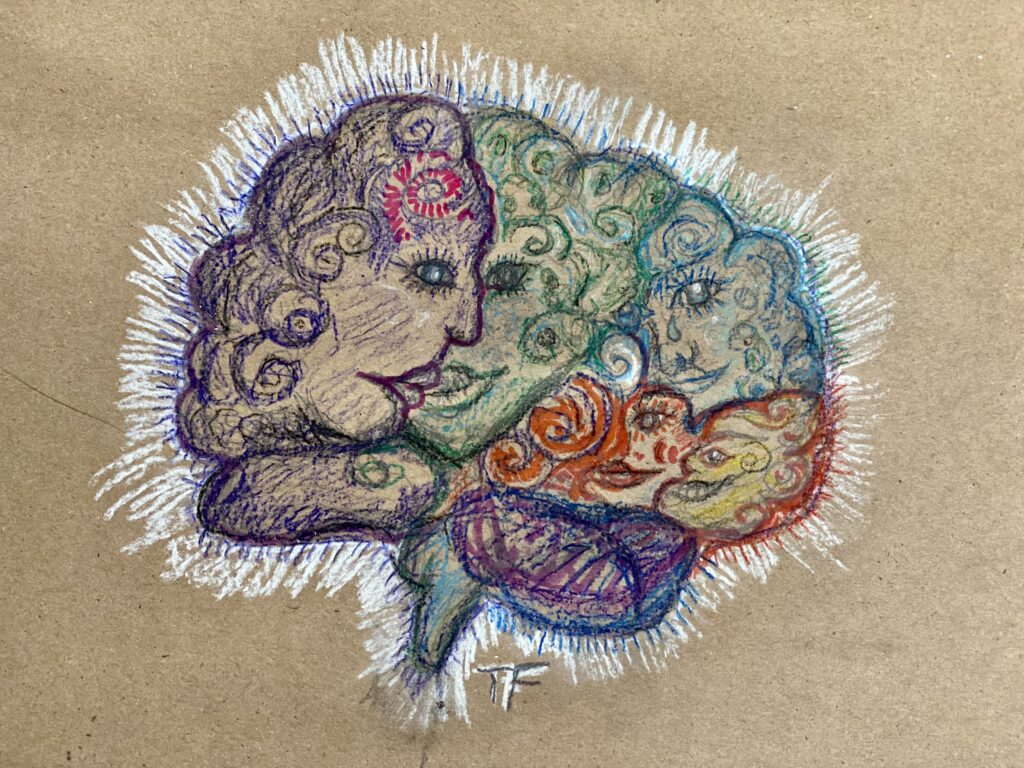

On two mornings in September, we visited p:ear to consider our faces, and facial expressions, and how we recognize and respond to each other in both art and life. Faces offer essential information about our social circumstances, and humans are visually attuned to faces, a bias present in infants.

LEARN MORE: Face perception and processing in early infancy: predispositions and developmental changes

Do you see faces?

Many of us perceive LOTS of faces, even in various inanimate objects, and respond emotionally to the expressions we find. Recognizing faces where no human or animal faces exist is known as face pareidolia, and the experience engages the same areas of our brains activated by actual faces.

And of course our perception of these faces is very real to us.

Though not everyone sees faces

About 6% of the U.S. population has face blindness, or prosopagnosia – they do not perceive faces. To recognize people they often rely on other stimuli, including glasses or specific hairstyles, or even how someone moves. And sometimes, as we’ve discussed with youth at p:ear, people with intact face processing fail to acknowledge other people as fellow human beings, a distressing and dangerous phenomenon known as dehumanized perception.

LEARN MORE: Neural mechanisms underlying visual pareidolia processing

LEARN MORE: Face Pareidolia Recruits Mechanisms for Detecting Human Social Attention

LEARN MORE: Brain activity underlying face and face pareidolia processing

LEARN MORE: Prosopagnosia (NIH)

LEARN MORE: Progress in perceptual research: the case of prosopagnosia

LEARN MORE: Seeing us all through research & art

Visual perception takes place in cortex

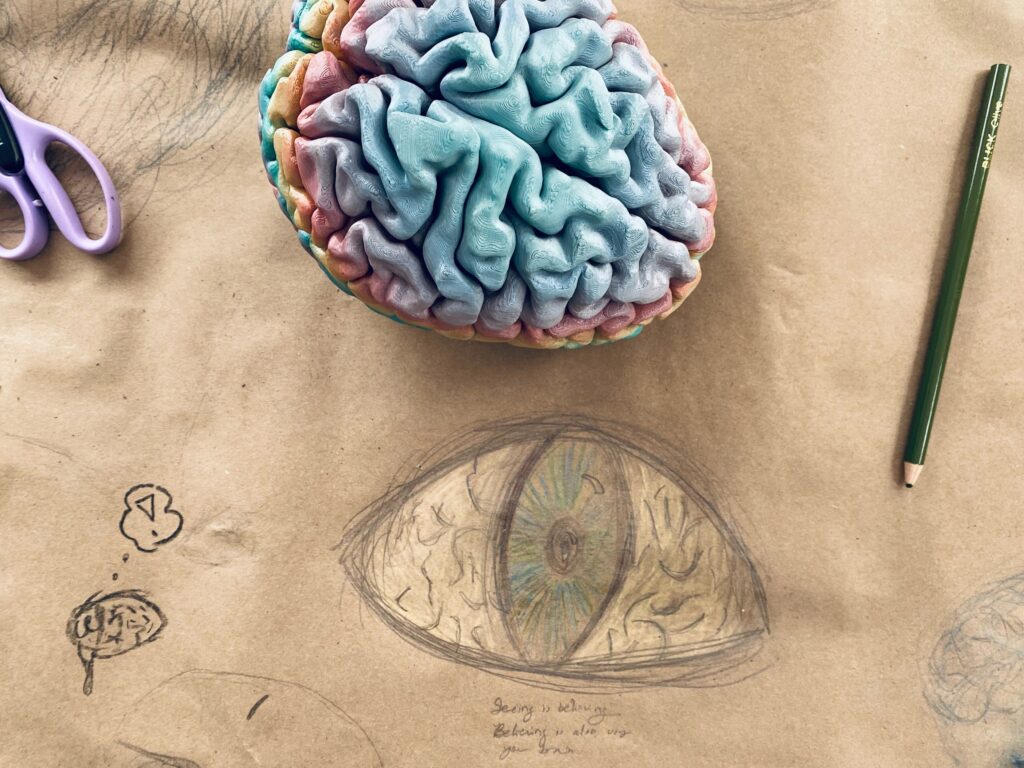

“We see with the eyes, but we see with the brain as well.”

–Oliver Sacks

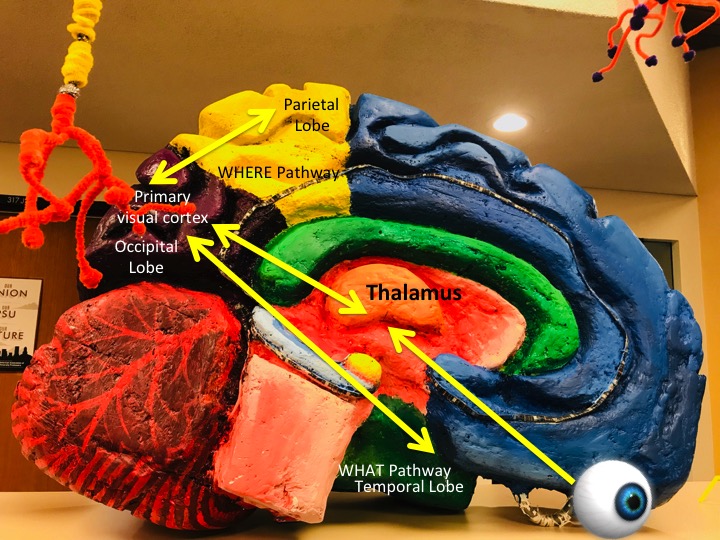

The yellow arrows below represent some of our neural pathways (axons), and trace how visual information from our eyes first arrives in the occipital lobes, chunks of cortex (the brain’s wrinkled outer “bark”) at the back of our head.

However, those neurons in primary visual cortex (or V1) then project their own wiry axons from the occipital lobes into the temporal lobes, routing details about color, shape and form into selective temporal regions that underlie our ability to quickly grasp WHAT it is we’re seeing, including cars, bikes, a cup of coffee, human brains – or FACES.

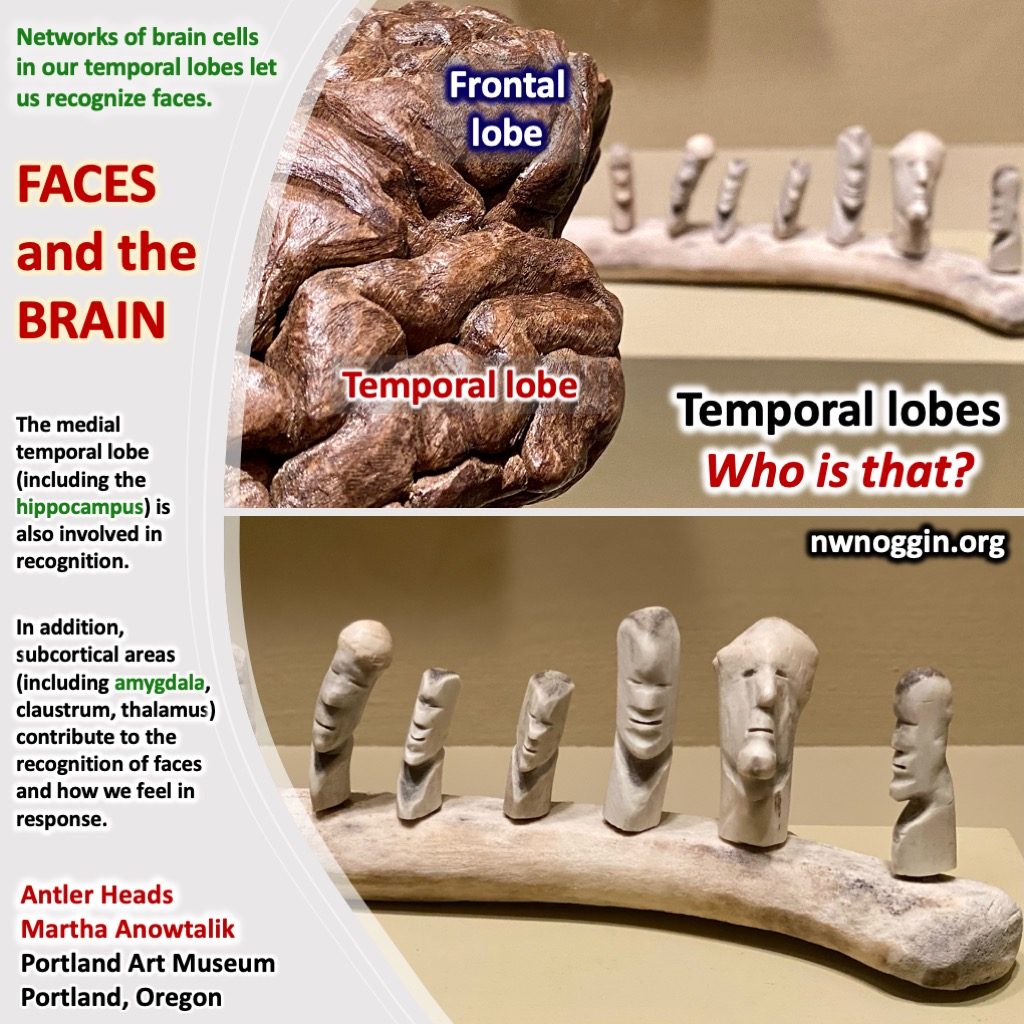

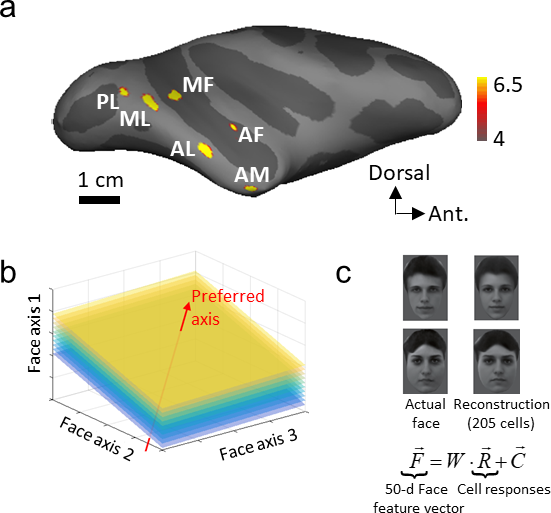

Doris Tsao, a neuroscientist at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology), has dramatically enhanced our understanding of the temporal lobe face recognition network in the primate brain.

“Faces are among the most informative stimuli we ever perceive: Even a split-second glimpse of a person’s face tells us their identity, sex, mood, age, race, and direction of attention. The specialness of face processing is acknowledged in the artificial vision community, where contests for face recognition algorithms abound. Neurological evidence strongly implicates a dedicated machinery for face processing in the human brain…”

–Doris Tsao

LEARN MORE: Mechanisms of face perception

LEARN MORE: The Code for Facial Identity in the Primate Brain

LEARN MORE: FACE PROCESSING SYSTEMS: FROM NEURONS TO REAL WORLD SOCIAL PERCEPTION

Talking, Drawing and Holding Brains

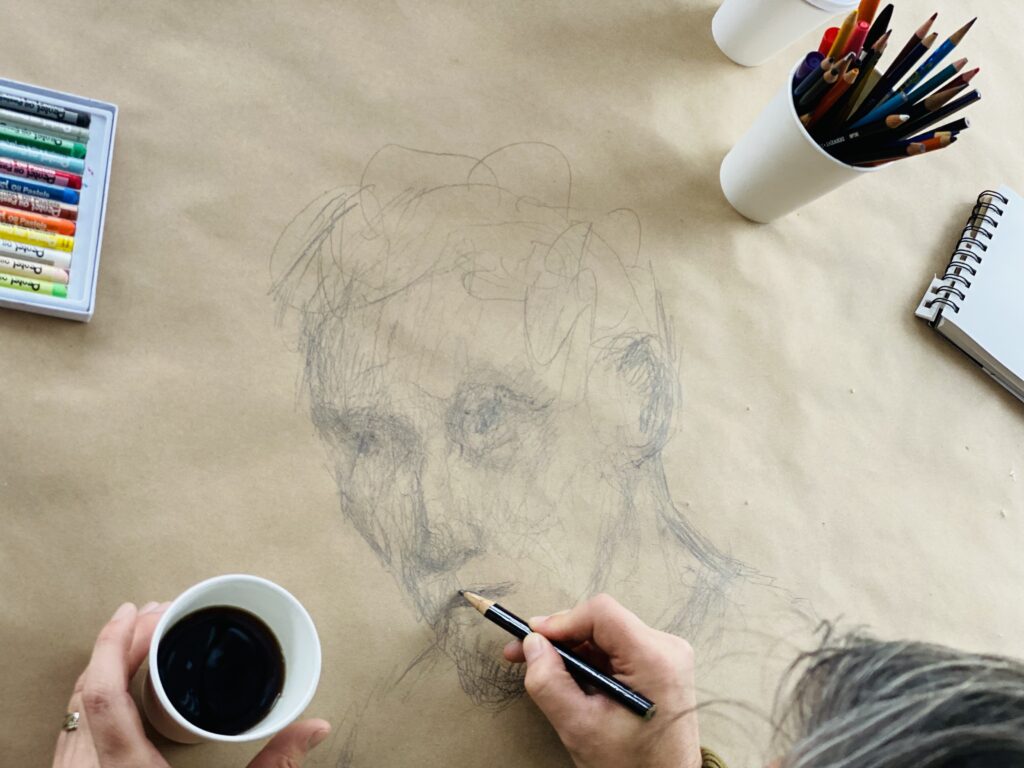

At p:ear we drew faces, discussed faces, considered faces – and also examined real noggins while exploring the many exciting questions that curious young people asked our volunteers.

LEARN MORE: Is there such a thing as a photographic memory? And if so, can it be learned?

LEARN MORE: Behavioral and neuroanatomical investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory

LEARN MORE: Visual long-term memory has a massive storage capacity for object details

LEARN MORE: The face of fear: Effects of eye gaze and emotion on visual attention

LEARN MORE: Elevated amygdala response to faces and gaze aversion in autism spectrum disorder

LEARN MORE: NIH Kuru Information Page

Our enthusiastic outreach volunteers included Becky Martinez, an NIH BUILD EXITO scholar at Portland State University, Quinn Westlynd, Ronan Peck, Tiara Freeman, Maria Coyner, Krystal Khanh Nguyen, Sara Moreno, James Reynolds, Jessie Sheeran and Greyson Moore, also from from PSU, and Denesa Lockwood from OHSU.

Noggin Art Coordinator and artist Jeff Leake also offered us a fascinating tutorial on drawing faces.

From Maria Coyner, undergraduate at PSU

“I thought today was one of the most unique experiences I had witnessed. I was almost starstruck by the amount of passionate people who were able to mesh between two worlds of art and science. Two worlds that do not always coincide with one another; that usually butt heads (ha!), as one is viewed (by some people) as very logical and mathematical and one is viewed as more unstructured and free flowing.”

“It was such a beautiful sight to see so many people from various backgrounds come together. Even the folks that simply wanted to stop by for resources all wanted to know what the heck we were doing. Whether or not this activity truly peaked their interests, they were curious enough to want to ask about what we were doing.”

“At one point I found myself in a conversation with another volunteer who worked as a scientist at OHSU. I mentioned to her that I could never be a scientist myself. Her response was, ‘Anyone can be a scientist if they have curiosity and a desire to learn more and ask questions.’ What a stunning answer. I think we all walked out of p:ear today having a little more scientist in our grasp than we realized.”

“Thank you so much for all you and Noggin do for p:ear youth. The resources, engagement and educational opportunities you are creating for Portland’s homeless youth population are unmatched. Seriously, UNMATCHED..

–Will Kendall, Art Program Coordinator, p:ear

Thank you, can’t wait until next time.”

Thanks to all of our outstanding volunteers, as well as the extraordinary young people and our colleagues and collaborators at p:ear!