Post by Madeline Ogle, Psychology undergraduate at Portland State University and NW Noggin outreach volunteer

As the dark Washington sky barely hinted at the promise of a slightly brighter day, I checked in at the Fort Vancouver High School office with my fellow outreach volunteers.

This was Friday of Finals Week at Portland State University, and over 20 of us decided that a great way to celebrate the end of term was to wake before dawn on one of the shortest days of the year and return to public school!

We were led through winding hallways covered by murals depicting the history of the universe, from the Big Bang to ourselves, and settled into the science classrooms where NW Noggin was stationed for the day.

For the first class, which began at 7:20am, I was immediately struck by one thing – many students were more or less asleep!

And I couldn’t blame them, as I felt only half awake myself, even with all the donuts and coffee (thank you Fort Biology teachers CoreyAnne Russell and James Cederstrom, and PSU student Lesley Guerra for the caffeine!).

LEARN MORE FROM FORT TEACHERS: What will your students remember in five years?

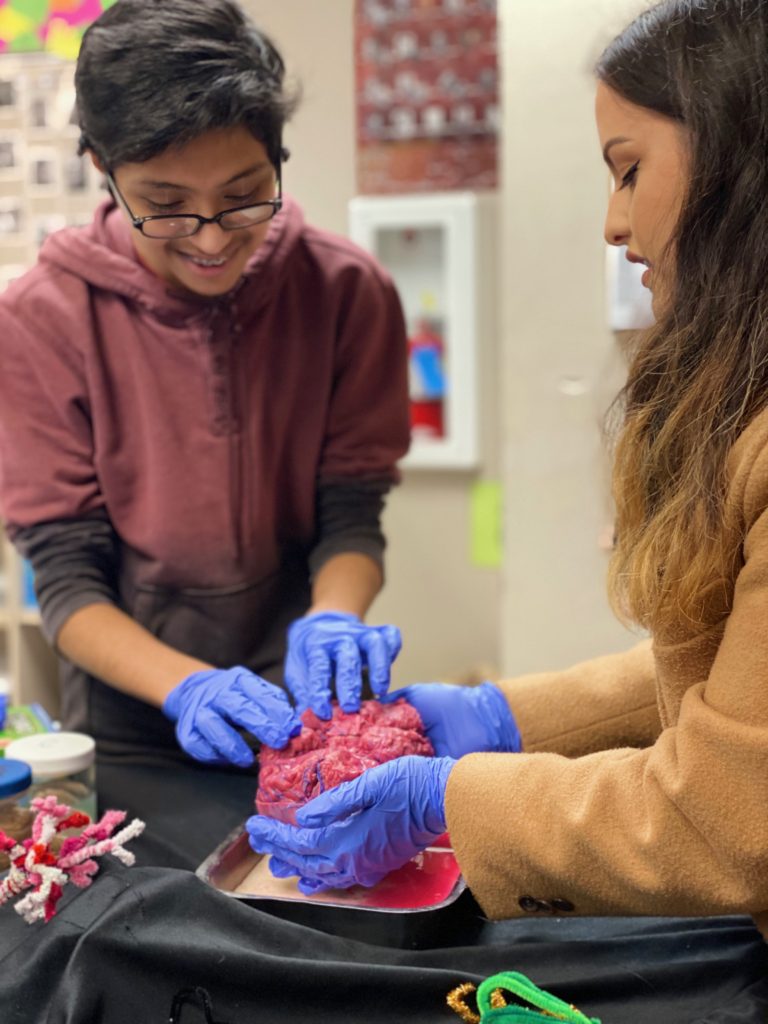

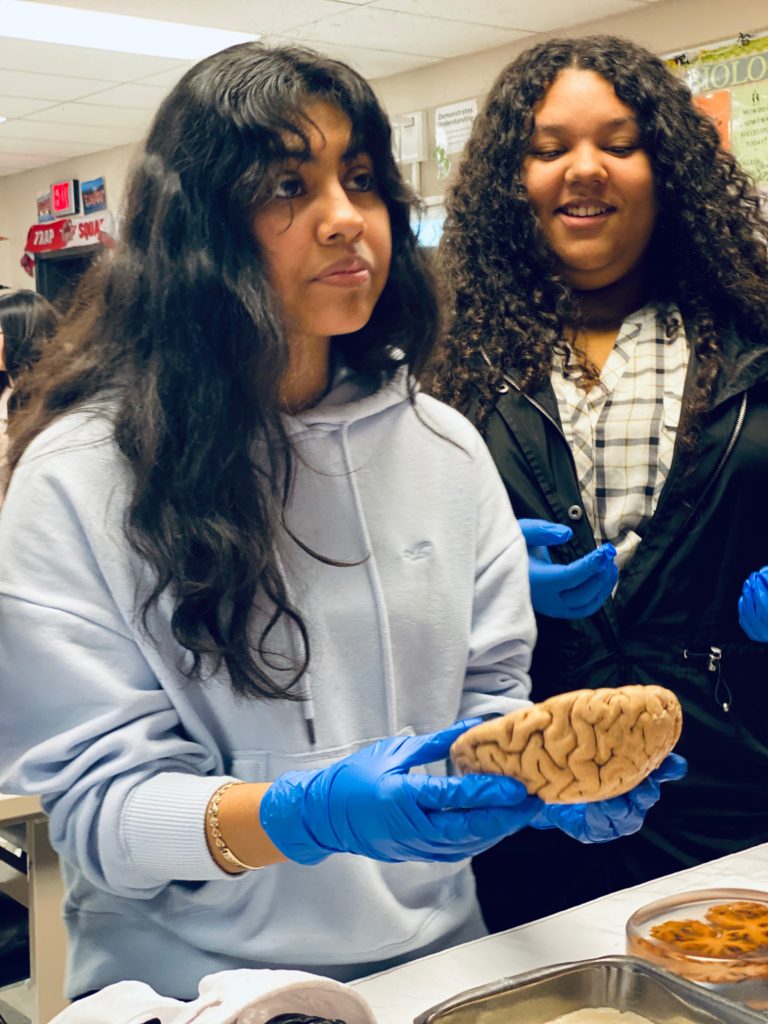

Students perked up, however, when we brought out our brains, and started asking everyone what they already knew or were curious to know about research on the brain.

LEARN MORE: The times they are a-changin’: cohort effects in aging, cognition, and dementia

LEARN MORE: Psychopathy & brains

The second class was livelier, and by the third, we had even more participation! It was clear that later school start times would help high school students attend and engage more.

Sleep helps your brain clean itself out, as waves of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can work their way through the central nervous system alongside tiny capillaries. LEARN MORE: The Glymphatic System – A Beginner’s Guide

When we talked with students about all the neuroscience research supporting the extensive benefits of morning sleep for adolescents, it provoked a vehement call to action.

LEARN MORE: Brains, biofeedback & SLEEP

LEARN MORE: Everything but guns

LEARN MORE: Sleep habits, academic performance, and the adolescent brain structure

LEARN MORE: School Start Times, Sleep, Behavioral, Health, and Academic Outcomes

LEARN MORE: Noggins in Nod

May we expect a student protest for later start times in the new year? The research supports this – so let our students sleep!

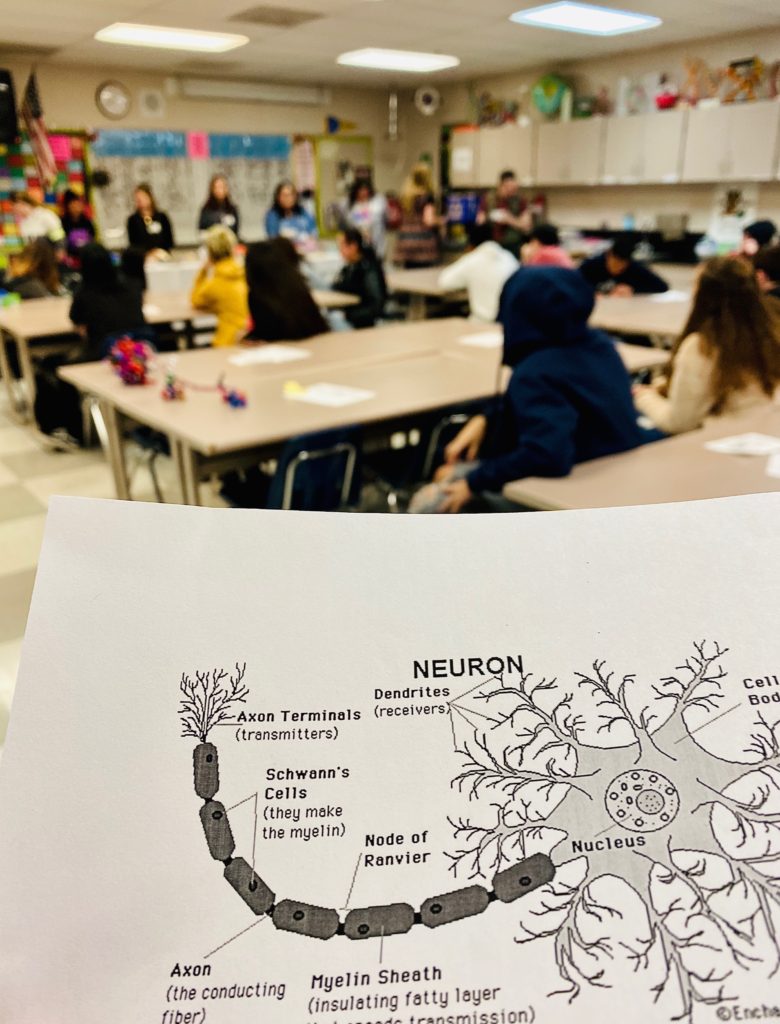

I enjoyed hearing so many fun and interesting observations throughout the day, especially when we could talk with students in smaller groups, while making pipe cleaner neurons, playing with electric control over our own muscles (and our friend’s muscles!) and of course holding and examining brains.

LEARN MORE: Make your own pipe cleaner neuron

LEARN MORE: Brain Hacking is Electric!

One girl asked me, “My friend did mushrooms the other day. Is her brain fried? Is she still the same person? Is she crazy now?”

I haven’t yet taken the Psychopharmacology course at PSU, but it was fun to discuss the growing field of neuroscience research on the therapeutic potential of some psychedelic drugs.

LEARN MORE: A less self-centered and more creative life

LEARN MORE: Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study

LEARN MORE: Psychedelic Portland

However I emphasized that these studies were done in adults, and in supportive, professional settings, and that setting appears to be critically important, as is knowledge of what substances are actually in a particular mushroom.

I also explained that adolescence through early adulthood is a sensitive time for brain development, when substances of any sort might have more dramatic, and sometimes dangerous, effects.

LEARN MORE: Exposure to Potent Hallucinogens in an Adolescent: A Case for High Index of Suspicion

LEARN MORE: Adolescent Brain Development and Drugs

Another student was incredibly interested in the different shapes of neurons, especially the cells in the inner ear (they had received some damage to their ear as a child).

I’d recently taken the Perception class at Portland State, where we made inner hair cells out of pipe cleaners, and it was fun to review the process through which sound waves travel through the ear and are eventually picked up by these waving, ciliated cells.

LEARN MORE: How Do We Hear?

LEARN MORE: Anatomy, Head and Neck, Ear Organ of Corti

They asked if these hair cells are what make them feel dizzy when they have vertigo, and when I told them about the vestibular apparatus, which also has hair cells, and how tiny limestone rocks called otoconia can move them and play into our sense of balance and acceleration, they were really intrigued! And also a little grossed out (there are rocks in my head?!).

LEARN MORE: Physiology of the Vestibular System

LEARN MORE: Vestibular system: the many facets of a multimodal sense

LEARN MORE: Mechanisms of Otoconia and Otolith Development

LEARN MORE: The Otolith Organs: The Utricle and Sacculus

LEARN MORE: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

My favorite part of outreach is simply getting asked why I study the brain. There is so much that is not yet known, I said. To me, it feels like the final frontier.

The key to curing disorders, helping to improve society, make better policies, and advancing the limits people can reach with their minds and bodies lies in a deeper understanding of this lump of white and gray (and pink!) matter in our heads!

Seeing interest getting sparked in those kids was really the greatest part of the day at Fort Vancouver.

Our sincere thanks to Fort students, teachers and staff!

And thanks, as always, to our astounding, community engaged volunteers, including (on the Friday of Finals Week, beginning at 7:15am!) post author Madeline Ogle, and Cam Howard, Danny Gray, Emanuel Heller, Katie Hashimoto, Sydney Duran, Jessica Cary, Julia Schmidt, Greyson Moore, Lidia Echeverria, Maria Galvan-Bravo, Lesley Guerra, Noemi Martinez, Paul Delahanty, Cameran Nicholas, Sai Kiersarsky, Liliana Prychyna, and Cassie James from Portland State University, Aaron Eisen from the National University of Natural Medicine and David Marmarinos from Portland Community College!

What’s happening in the brains of

What’s happening in the brains of

(link in bio)

(link in bio)