Post by Jordan Ray, Portland State University

“Even the knowledge of my own fallibility cannot keep me from making mistakes. Only when I fall do I get up again.” –Vincent Van Gogh

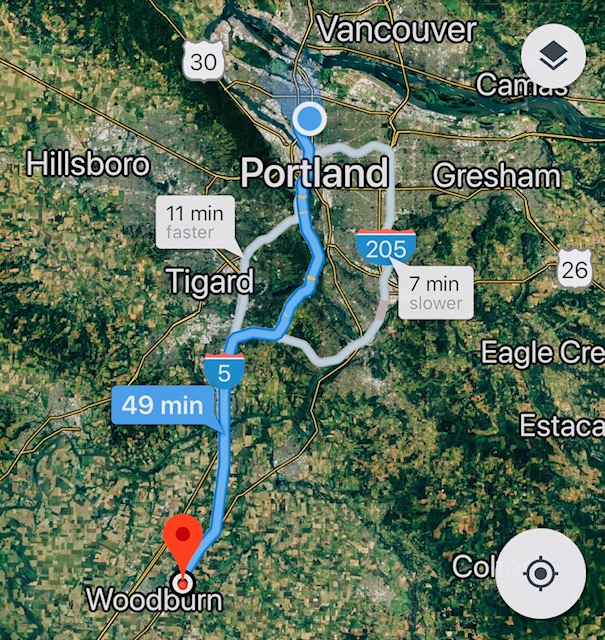

This week we drove south to the Willamette Valley city of Woodburn, Oregon, where the annual Fiesta Mexicana was getting underway. Originally Kalapuya Indian land, Woodburn is surrounded by tulip nurseries, fragrant hop farms, a vast, interstate-adjacent outlet mall, and the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, where over 200 boys and young men (ages 12 – 25) are confined. MacLaren is administered by the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), a state agency with a mission “to protect the public and reduce crime by holding youth accountable and providing opportunities for reformation in safe environments.”

MacLaren offers a number of vocational programs, including the training of shelter dogs through Project POOCH. The Hope Partnership, a collaboration between OYA and Janus Youth Programs, also provides classes and community networking opportunities at MacLaren for young people to help build self-confidence and the skills needed to transform their lives.

LEARN MORE: Hope Partnership Celebrates its Fifth Year Anniversary

LEARN MORE: Janus Youth Programs – Residential & Re-Entry Services

LEARN MORE: HOPE Partnership – Janus Youth Programs

Earlier I’d reached out to Kathleen Fullerton, the Program Coordinator for HOPE, and on Friday I motorcycled through rush hour traffic to Woodburn to join Jacob Schoen, a Noggin Resource Council member from OHSU (the Oregon National Primate Research Center) and Bill Griesar, the Neuroscience Coordinator for Noggin and a senior instructor at Portland State.

We were there to discuss neuroscience, answer questions, and see if people were interested in learning more. At MacLaren, we sat with youth leaders who were extremely curious about very relevant topics. We were asked, for example, about bias in judicial and law enforcement systems, about pathways in psychology for counseling and research, and what role neuroscientists play, or might play, in judicial and legislative reform. Native American, Black and Latino Oregonians are incarcerated at disproportionate rates, and youth inside the facility are looking for changes in police, courtrooms and public policy to address implicit and explicit bias affecting these environments.

Statue by Ronald S. McDowell, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama

LEARN MORE: Over- Representation of Minority Youth in Oregon’s Juvenile Justice System

LEARN MORE: Race, Bias & Brain: You Can’t Control Art

LEARN MORE: Prospective teachers more likely to view black than white faces as angry

LEARN MORE: The insidiousness of unconscious bias in schools

LEARN MORE: Are “Stand Your Ground” Laws Racist and Sexist? A Statistical Analysis of Cases in Florida, 2005–2013

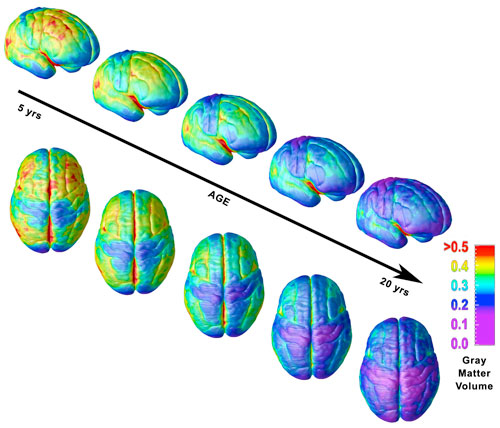

Oregon also has one of the highest youth incarceration rates in the country. Many at MacClaren are seeking to repeal Oregon Ballot Measure 11, a “minimum sentencing” law passed by Oregon voters in 1994. The law sets minimum sentences for “serious crimes against persons” and requires defendants aged 15 and older to be tried as adults. Judges in Measure 11 cases have limited discretion in how sentences are handled, which can lead to teens taking questionable plea deals to avoid excessive outcomes. These young people at MacLaren are currently studying the law and aspects of neuroscience (including adolescent brain development) that are relevant to how our justice system operates, in order to bolster a case for repeal.

LEARN MORE: Oregon Incarcerates Youth At Higher Rate Than Most States

LEARN MORE: Report blasts Measure 11’s ‘harsh sentences’ for Oregon youths

LEARN MORE: Adolescent Risk Taking, Impulsivity, and Brain Development: Implications for Prevention

LEARN MORE: NIH releases first dataset from unprecedented study of adolescent brain development

LEARN MORE: Youths branded by Measure 11

IMAGE: It may seem counter-intuitive, but the volume of “gray matter” (i.e., the number of neurons, and number of synaptic connections) actually drops in the frontal lobes during adolescence, as our neural wiring grows more specialized and efficient for the activities and behaviors we pursue…and are able to prevent.

This intersection of brain research and law is of great current interest. David Eagleman, a prominent neuroscientist at the Baylor College of Medicine, is co-Director of the Center for Science & Law, a new organization designed to “harness neuroscience, data science, and legal research to advance justice.”

LEARN MORE: The Brain on Trial

In a 2016 publication, Dr. Cara Altimus, a neuroscientist at the Milken Institute, wrote that “neuroscientists are privy to knowledge that has not yet reached the court systems; knowledge that has the potential to be incredibly impactful…”

“As neuroscientists, our understanding of one of the most complex biological systems known has the potential to change the way the justice system operates. Although it may go against the scientific norm of distance and neutrality, society as a whole, and the criminal justice system in particular, would benefit from active collaboration between the neurological sciences and the criminal justice system. The payoff for all of us could reach as far as it has in traditional medicine.”

LEARN MORE: Neuroscience Has the Power to Change the Criminal Justice System

These are critical questions, with significant consequences for our communities, and for children’s lives. How does bias in the brain set the precedent for sentencing laws? What kind of biases and stereotypes work against communities here in the Pacific Northwest in arrests and sentencing?

Many thanks to Kathleen, Janus Program Facilitator Melinda del Rio, and young people at MacLaren for welcoming us past the gates.

We look forward to further discussions and insights on neuroscience research and the law. We’re scheduling a full afternoon in September for more questions and an update on student progress regarding Oregon’s Measure 11.

Stay tuned. One of the many ground squirrels at MacLaren