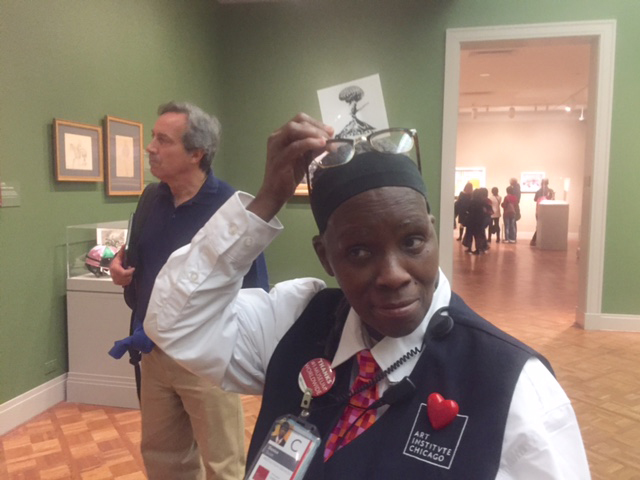

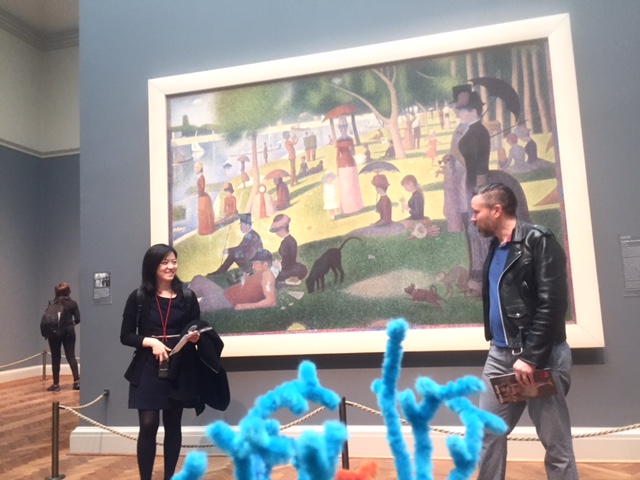

In light of our recent work with the Portland Art Museum, we decided to take our trusty pipe cleaner neuron down to the Art Institute of Chicago. We were in the city attending the 2015 Society for Neuroscience conference, and enjoyed an afternoon re-imagining some famous works of art.

LEARN MORE: In Dialogue with Art and Drugs @ PAM

LEARN MORE: Brains on Art: Member Night @ the Museum

LEARN MORE: The Nature of Seeing: Noggins and Art

LEARN MORE: Posters, Politics and the PPA

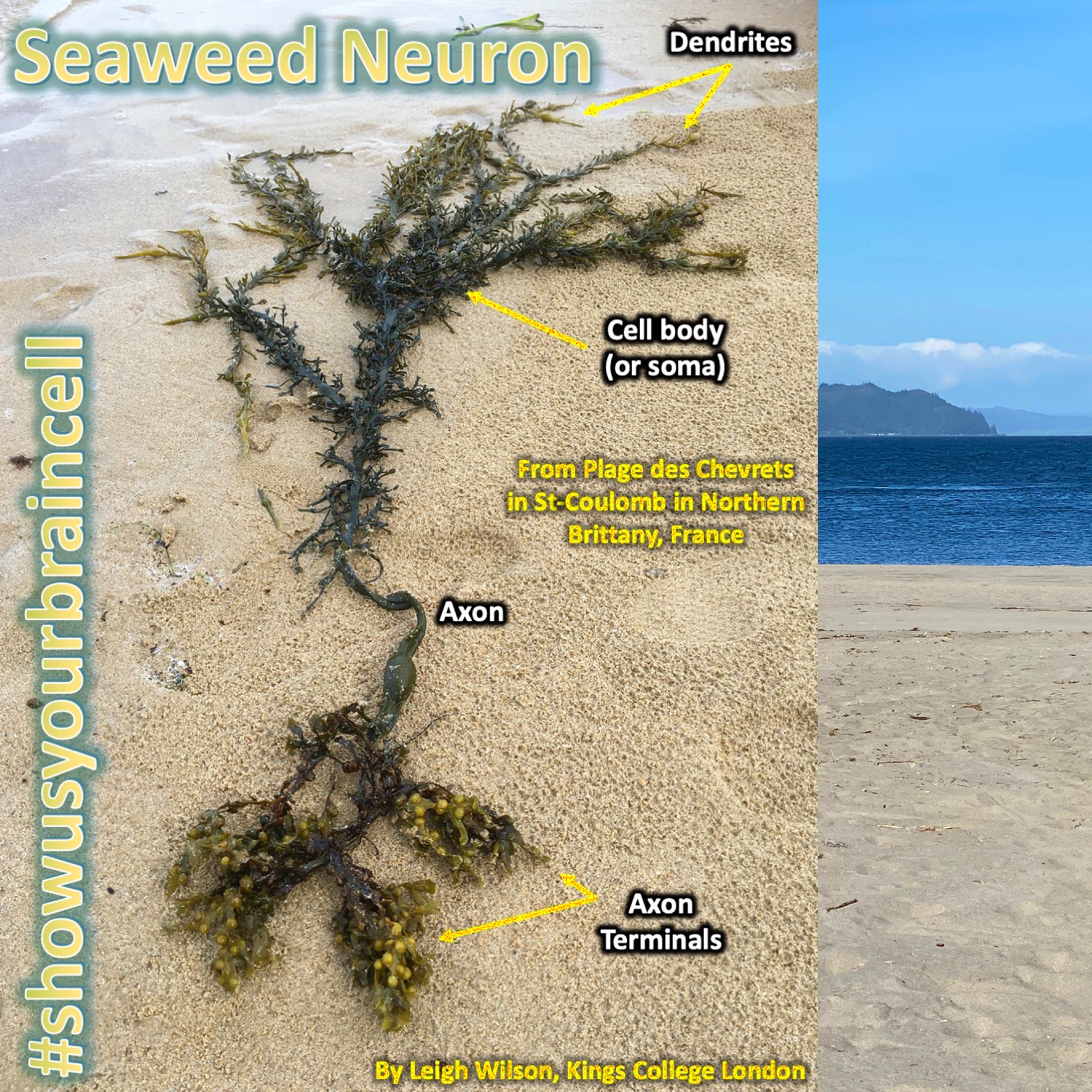

People were very curious to know about the connection between our fuzzy little brain cell and some incredible paintings, and we were happy to enjoy impromptu outreach regarding the links between neurons and art…

We looked at Monet’s “Waterlilies,” and thought about the possible effect that his failing eyesight might have had on his work. I noted that in his later paintings, he begins to remove many of the spatial cues that were prevalent in his earlier scenes, like the one below…

LEARN MORE: Eye diseases changed great painters’ vision of their work later in their lives

For example, in order to focus on a freer use of color, Monet largely eliminated horizon lines from these paintings, effectively removing that illusion of deep space typical of many landscapes

This is partly a result of ambiguous or conflicting information flowing along the brain’s visual “where” pathway from the primary visual cortex into networks in the parietal lobes. (Of course, a high contrast neuron in the foreground definitely helps restore a sense of depth to these photos, above!)

LEARN MORE: Giant brains @ p:ear!

As we moved into the American section of the museum we came across this striking work called “The Palisades,” by George Bellows. I was fascinated by how different our responses were to this image, and it reminded me of new research from the Society for Neuroscience nanosymposium on the cortical representation of visual scenes that we had attended the previous day.

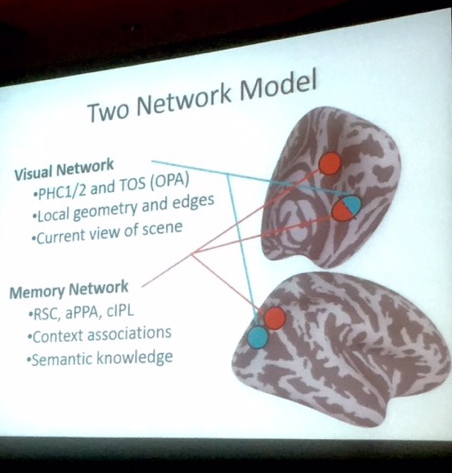

In particular, data presented by Christopher Baldassano from Princeton University suggested that we have (at least) two distinct cortical networks involved in processing visual landscapes, one involving the posterior PPA (parahippocampal place area) that is partly responsible for identifying types of places based on their specific individual features. However, the anterior portion of the PPA, which links into the larger “default network,” appears more involved in recalling personal memories that relate to that place or type of place.

LEARN MORE: Two Distinct Scene-Processing Networks Connecting Vision and Memory

LEARN MORE: Scene Perception in the Human Brain

The interaction of these two networks seems to account, at least in part, for the broad array of interpretations that artwork evokes (particularly landscapes in these studies). So while I was recalling how George Bellows tragically died of a ruptured appendix, and my other encounters with his work, integrating all of these memories with the visual scene to create a whole experience, Bill, who grew up in the Hudson valley where this image was painted, was able to recall commuting on the Metro North train from Dobbs Ferry to New York City in the winter.

These specific and detailed memories offer him far different feelings and reactions to this particular work.

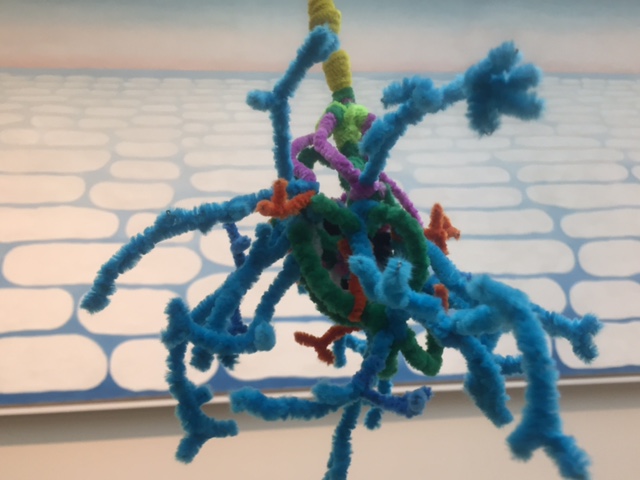

Our meandering path through the museum found us in the modern art wing looking at Lichtenstein and Pollock. In the Wait What webisode we produced for the Portland Art Museum, I had mentioned that as visual information cascades out from our primary visual cortex and down into the “what” pathway in the temporal lobes, we are constantly attempting to identify and categorize objects within our visual field. This produces particularly interesting associations when viewing abstract or non-objective work because whether we wish it or not our temporal lobes are hard at work trying to utilize past experience to make sense of what we’re viewing. Here Bill is very naturally seeing neural connections in this Jackson Pollock, above…

LEARN MORE: Wait what? Your brain on art!

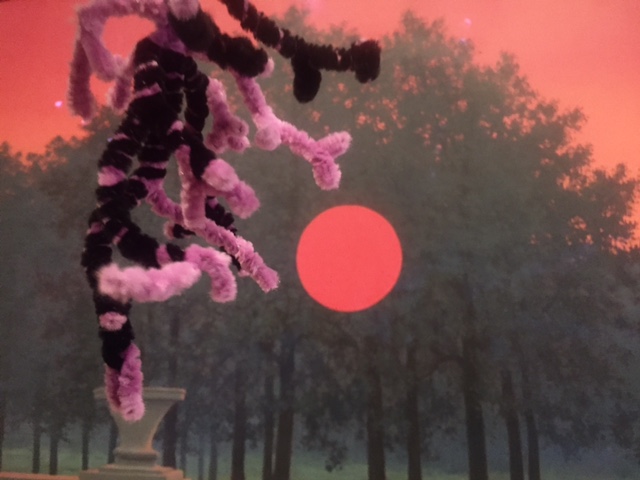

We ended our visit by taking a stroll through the museum’s superb collection of Surrealist works. I was struck in particular by this painting “The Banquet,” by Rene Magritte, who often uses familiar and identifiable imagery, presented in unusual and ambiguous or visually conflicting circumstances. These are particularly arresting because of their novelty. Unexpected juxtapositions can provoke the activity of nuclei in the brainstem, including the locus coeruleus, the source of a specific neurotransmitter known as norepinephrine. Norepinephrine release generates an “orienting” response; that is, it provokes the coordinated swiveling of your head, neck and eyes so that you find yourself looking at something unusual more closely. Novelty also provokes release of another neurotransmitter, called dopamine, and release of dopamine is linked to motivated behavior. A new or unexpected arrangement of familiar objects can be rewarding, and attract attention – for example, a neuron wandering around a museum…

A few additional pics from a reimagined museum…

“Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte, with Dendrites,” by Seurat

“The Drinkers, Happily Inhibiting Their Frontal Lobe Synapses,” by Van Gogh

“Ballet Dancers Demonstrating Basal Ganglia and Cerebellar Expertise,” by Toulouse-Lautrec

“Ancestors of Tehamana, with Soma and Dendritic Spines,” by Gaughin

“Sky Above Clouds, with Neuron,” by Georgia O’Keefe

“Neuro Gothic,” by Grant Wood

“Hogs Killing a Snake – and a Terminal Axon,” by John Steuart Curry

“Picture of Dorian Gray and Post-Synaptic Membranes,” by Ivan Albright

“Ohhh…Alright…Action Potential,” by Roy Lichtenstein