About the art and neuroscience of narrative by artist Jeff Leake

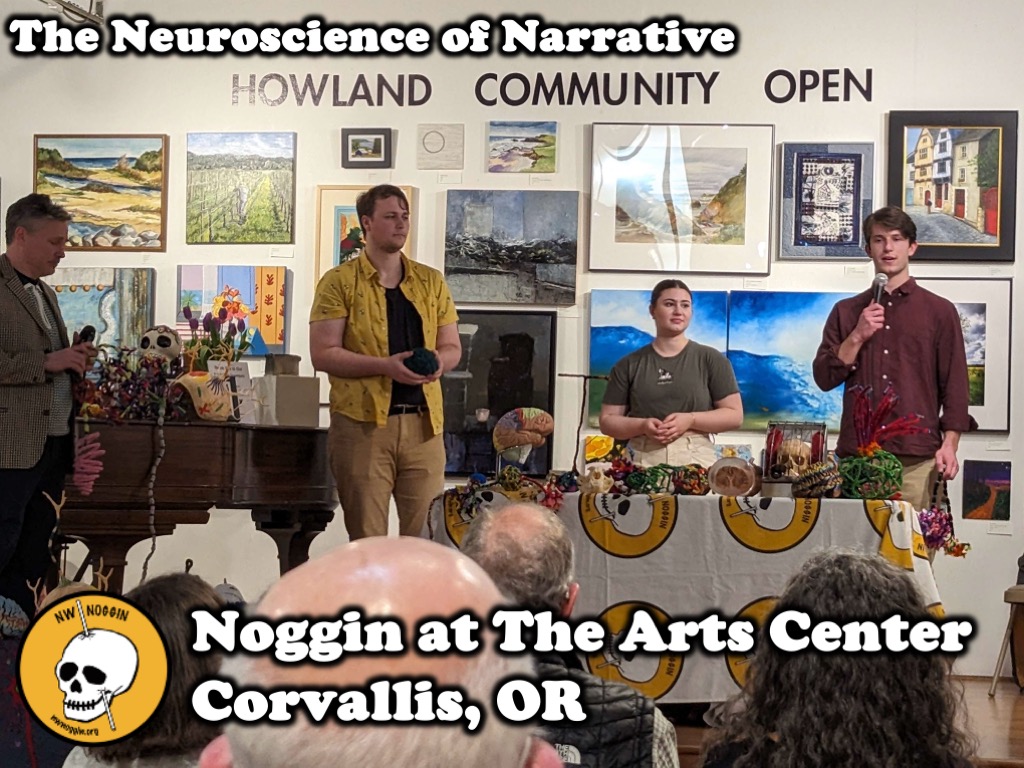

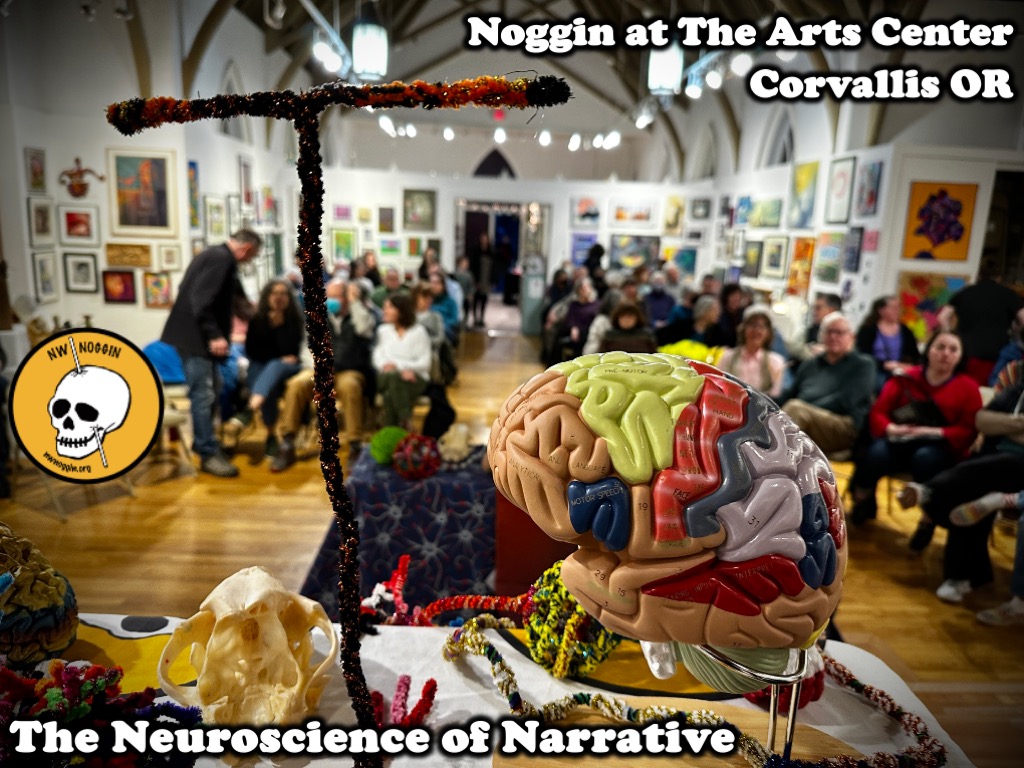

Bill Griesar and I kicked off the month of February with a discussion of brains and storytelling to open my show “New Mythologies” at the Corrine Woodman Gallery at the Art Center in Corvallis.

We also discussed many of these ideas in a series of public talks on the Science of Creativity (and the creativity of science!) organized by Caldera Arts, an extraordinary nonprofit that brings together public school students from Portland and central Oregon. I’ve also been thrilled to create art during two residencies at Caldera.

LEARN MORE: Caldera Arts and Brains in central Oregon

In May, Bill and I were honored to share the stage with Christopher Brown, an accomplished jazz musician, and Anis Mojgani, Oregon’s poet laureate in Bend, Sisters and Portland!

In Corvallis in February, Bill and I were joined in our presentation by fellow artist Kindra Crick, and Mark Chenard, Kate Lovetang and Justin Brenner from Portland State University.

We greeted a packed house with a discussion about Art, brains, and narrative.

We create meaning through stories

One concept of memory is that when we remember events that have happened, we are not simply recording and playing back what happened rather we are associating experiences within a narrative schema. A recent fMRI study at UC Davis’s Center for Neuroscience suggests that the hippocampus does more than just combine memories from similar experiences; it plays a crucial role in creating cohesive narratives that link distant events into memorable and easily recalled stories.

![2: Hippocampus cross-section rendered by Ramon y Cajal [19] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329948704/figure/fig2/AS:708496525893633@1545930143618/Hippocampus-cross-section-rendered-by-Ramon-y-Cajal-19.jpg)

LEARN MORE: The hippocampus constructs narrative memories across distant events

The other way to look at this is that through experience we create a story of who we are and we not only remember things better that are more coherent within that structure but we also bend those memories to fit within that narrative.

LEARN MORE: Constructing the Past: the Relevance of the Narrative Self in Modulating Episodic Memory

Not only does it seem critical to how we remember and how we arrive at a sense of self but it is conversely also a means by which, through the sharing of stories we might change, alter and expand our own narratives.

In my own work I often think about what stories others might invent around the visual narratives I create. These stories are often more interesting to me than my own, I think in part because they help me shift my own perspective. But also, I think this illustrates one of the things that is so innately special about art, music, and poetry in that it does not have a fixed meaning, rather it allows us to hold many equally valid ideas about the same thing. That sort of cognitive flexibility not only helps us as we encounter new experiences but also has the potential to change how we see ourselves and the world around us.

“In narrating a past experience, the narrator moves beyond an account of what happened in the world to include internal reactions, how and why things unfolded as they did, the thoughts and emotions of the participants, and what this means in terms of understanding the world and understanding relationships. Essentially, narratives of personal experiences tell a small story of human drama”

– Wallace Chafe

Adding noise to the system

We also discussed how the unexpected in art might increase our capacity to generalize our experiences. In examining machine learning Erik Hoel noted that one way for preventing systems from getting overfitted to the data they are trained on is to introduce a certain amount of randomness or “noise” into these systems. He suggested in his own “overfitted brain hypothesis” that art and fiction may be some of the means by which we keep our own brains from becoming overfitted to our experiences and become better able to accommodate new ones.

LEARN MORE: The overfitted brain: Dreams evolved to assist generalization

One of the things I greatly enjoy about these discussions is in talking to other people who are really interested in what we all might gain by experiencing the world through the lens of art and making. This led us all into a larger discussion around my own philosophy in education as well as one of the main drivers for what we do at NWNoggin.

I’ve written about this before (including in an article for SciArt magazine)

Why Art and Neuroscience?

Art and neuroscience may seem like two very different fields, but they share a lot in common. Both fields strive to understand what makes us who we are and how we relate to the world around us. Both also require creative thinking and problem-solving skills. Integrating art into neuroscience education can have a number of benefits for students.

Art Doesn’t Require One Right Answer

One of the reasons why art is so valuable in neuroscience education is that it doesn’t require one right answer. In fact, art often encourages us to think outside the box and come up with creative solutions that can accommodate a diverse range of approaches. My answer does not need to look like yours, but both can be equally valid and demonstrate an often complex understanding of a problem. This type of thinking is essential in science, where there are often many possible explanations for a given phenomenon. By integrating art into science education, we can encourage students to explore a variety of solutions and develop their problem-solving skills.

Art Makes Things Personally Relevant

Another benefit of using art in neuroscience education is that it makes things personally relevant. When we create art, we’re often drawing from our own experiences and emotions. By incorporating art projects into neuroscience lessons, we can help students make personal connections to the material they’re learning. This not only makes the subject matter more engaging and memorable; it can also help students see the relevance of science to their own lives.

Art Allows Us to Better See Each Other

Finally, art can help us better see each other. When we create art, we’re often expressing ourselves in ways that words alone can’t convey. By sharing our art with others, we can gain a deeper understanding of each other’s experiences and perspectives. This type of understanding is essential in neuroscience, where we’re often trying to understand the complexities of what makes us who we are. By incorporating art projects into neuroscience education, we can help students develop empathy and gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human experience.

More information on arts integration in education

LEARN MORE: Art of Learning – An Art-Based Intervention Aimed at Improving Children’s Executive Functions

LEARN MORE: The impacts of a high-school art-based program on academic achievements, creativity, and creative behaviors

In addition to this there are general cognitive benefits.

One suggestion is that art making produces an unusual connective state in our brains between two broad networks, the Default Mode Network, associated with rumination and planning, and the Executive Control Network (or “task positive” network(s)), associated with actively attending to a task or reaching a goal. Normally we see these networks suppress each other (when one is active the other isn’t), but when engaged in art making, they both appear to be active.

LEARN MORE: Brain networks for visual creativity: a functional connectivity study of planning a visual artwork

More recently studies have found that art making may even increase functional connectivity between many areas of the brain, but particularly within that Default Mode Network.

The intersection of art and neuroscience offers us profound insights into human cognition and creativity. Art not only helps us understand the intricacies of our minds but also provides a medium for expressing and reshaping our narratives. By integrating art into neuroscience, we foster a more holistic approach to learning and understanding, encouraging flexibility, empathy, and personal relevance.

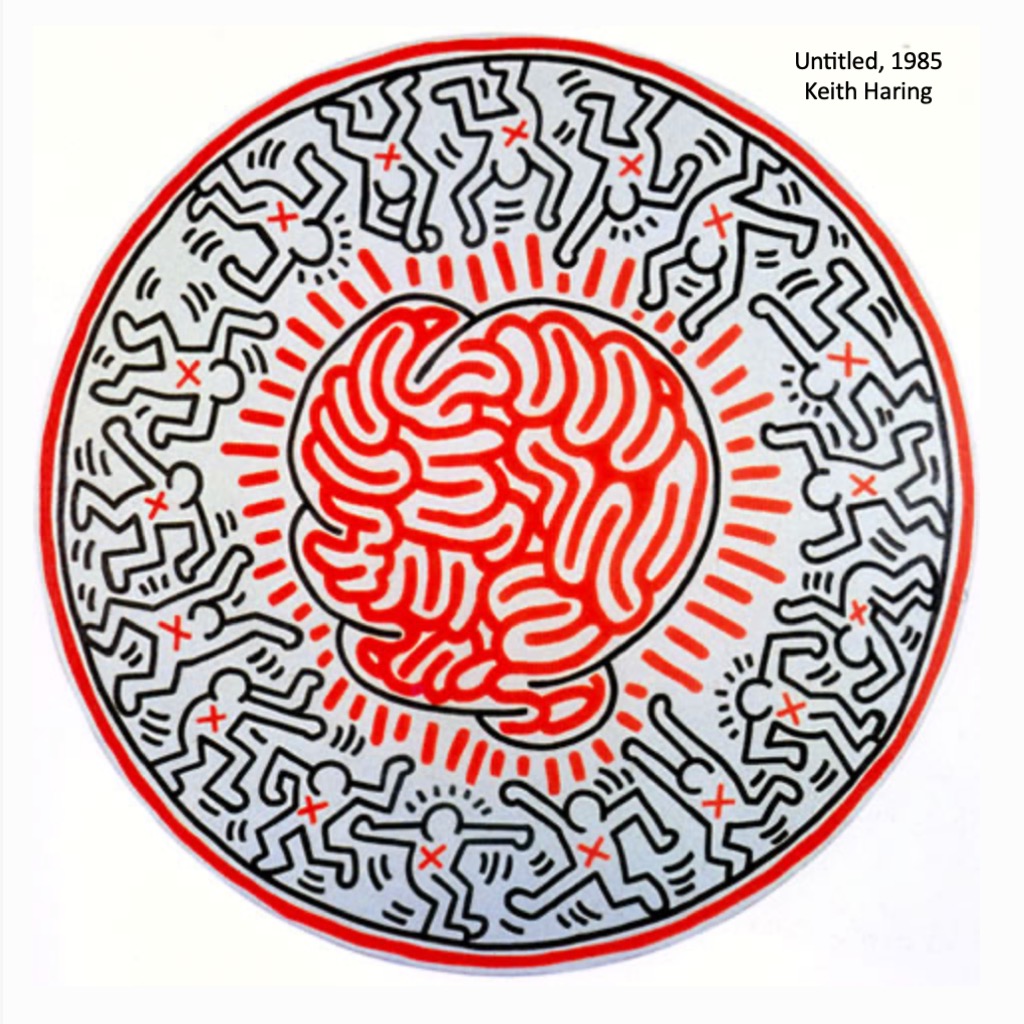

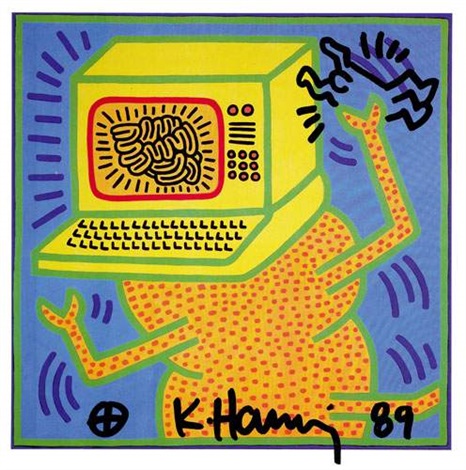

Keith Haring “Computer Brain” 1989

felt-tip pen on offset color lithograph

“People, I realize, cannot live like a patch of grass. They could, I suppose, at one time, but we are so far removed from that time that it is hard to conceive. People can, however, live their lives with the realization that they are constantly changing, products of their changing environment and changing situations, and time.”

– Keith Haring