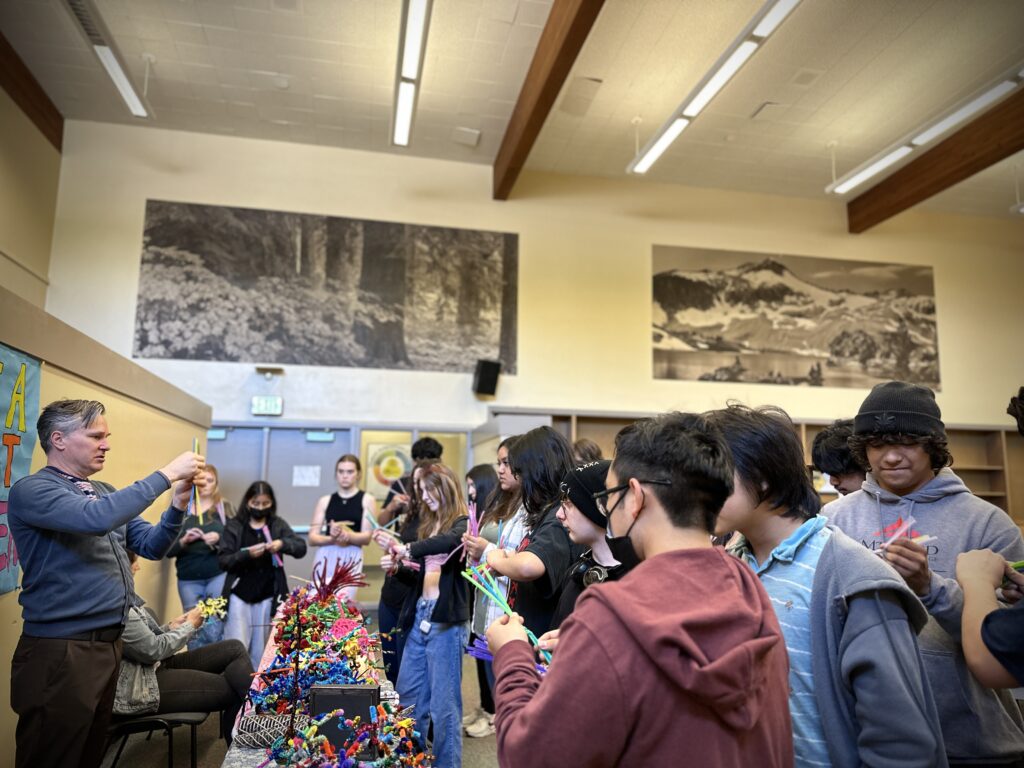

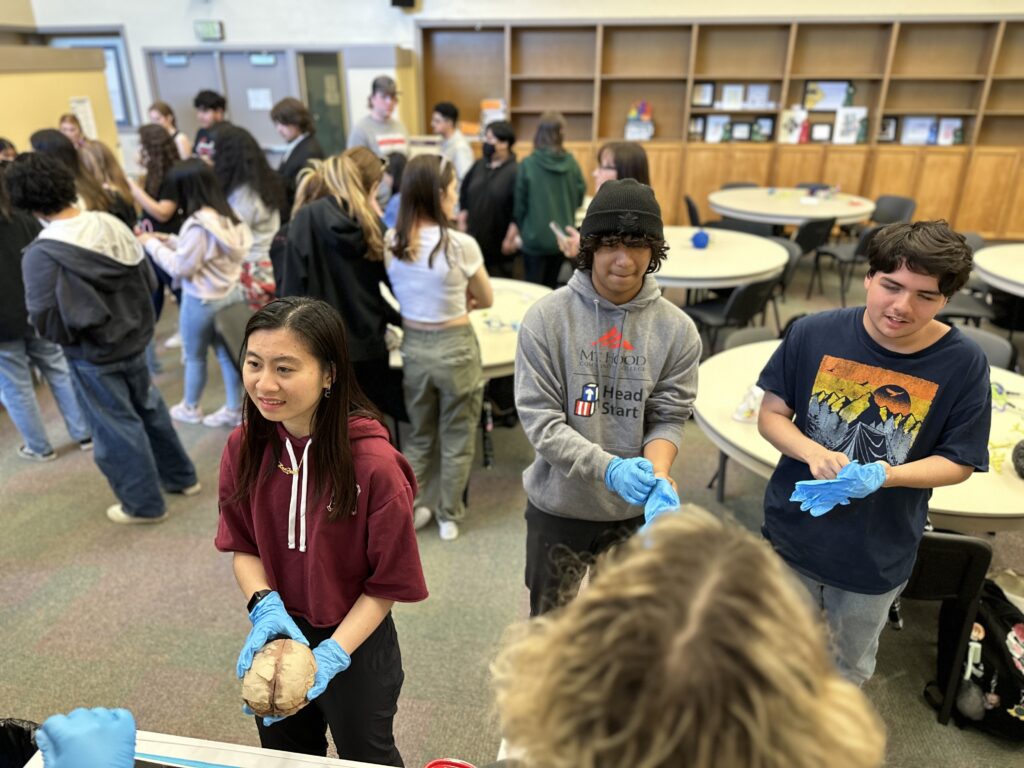

This month we joined sophomore, junior and senior classrooms at David Douglas High School in Portland, Oregon, at the invitation of Psychology teachers Heather Murdock and Tracy Lind. We’d visited David Douglas in the past, before the pandemic, and both teachers reached out to arrange for our return!

LEARN MORE: Inspiration & Education!

LEARN MORE: Everything but guns

Our neural volunteers included Dr. Denesa Lockwood from OHSU, Luis Carillo, a recent graduate in Psychology from Portland State University (PSU), and Veronika Carranza, Andy Ng, Cameron McGrew, Tonia Bautista and Rebecca Chevrel, all undergraduates in Psychology pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at PSU.

How to change a habit

David Douglas students had just completed individual four week research-based efforts to change a specific habit, and we spent the day discussing their experiences – and the brain changes involved.

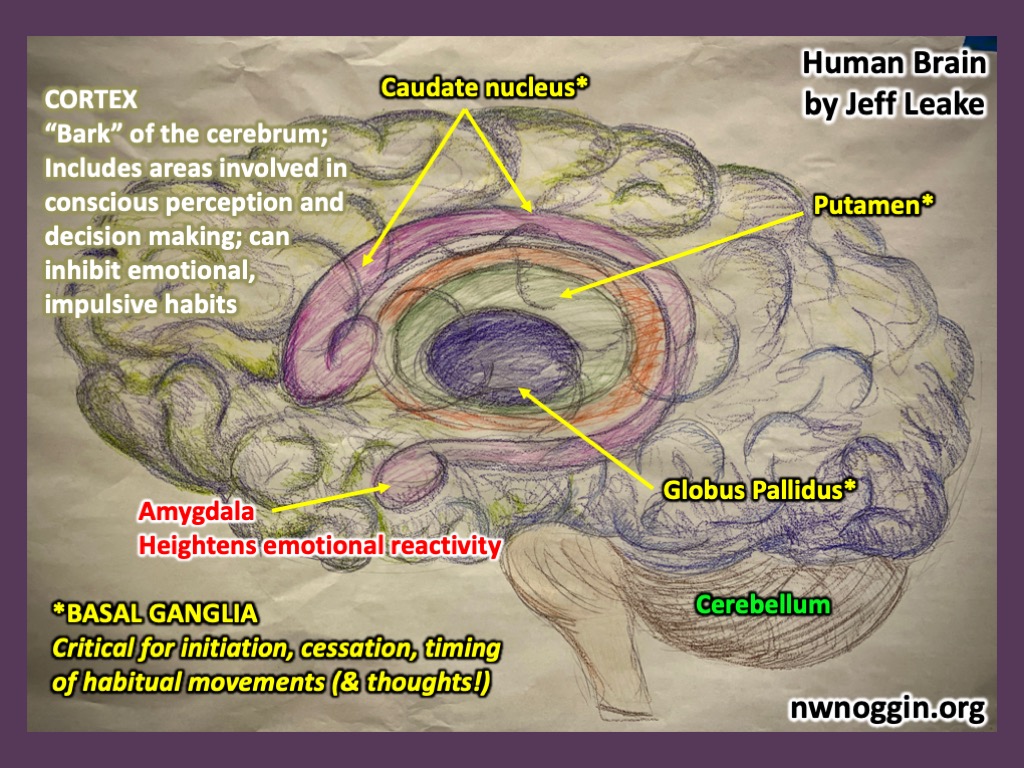

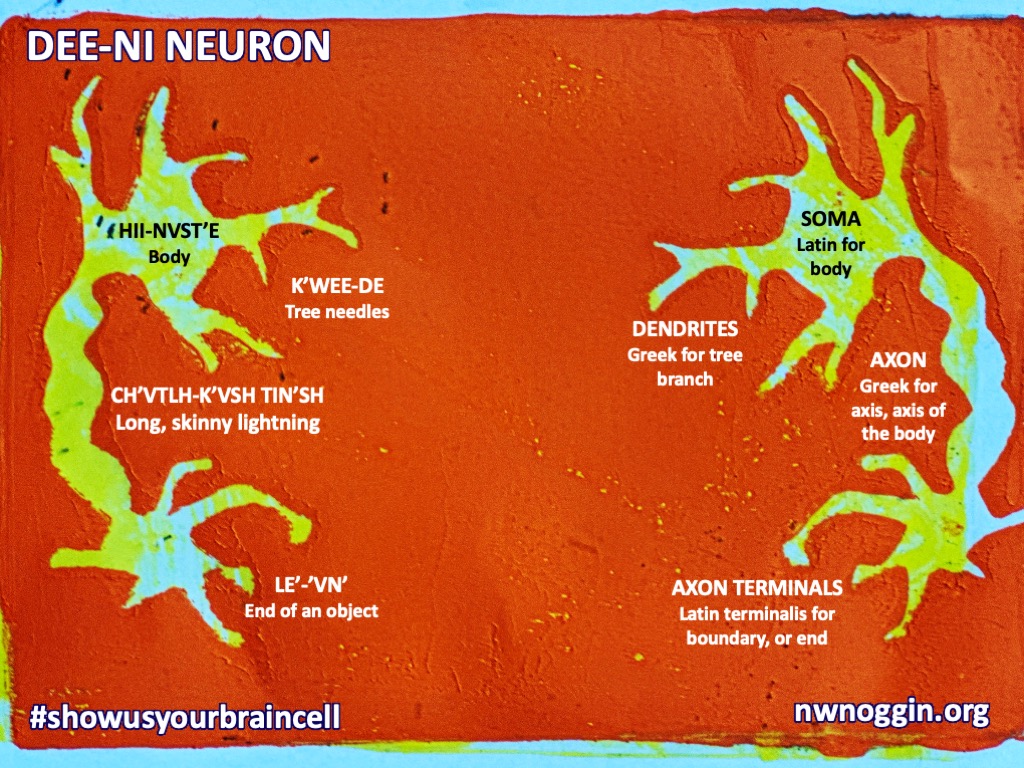

Habits are deeply ingrained in subcortical (below the cortex) circuits in brain regions like the basal ganglia and cerebellum, and it takes effortful, conscious, cortical network engagement to inhibit them, and to practice and acquire new learning for change.

Noggin has written extensively on this topic, and the importance of conscious deliberation, awareness and inhibition, and of course the practice, repetition and feedback from the inevitable mistakes we make that let us better re-wire our brains.

Your cortex (including social decision making networks in your frontal lobes) must ultimately provoke changes in deeper, subcortical basal ganglia and cerebellar circuits to inhibit the more automatic and reflexive habits you’re hoping to change. This takes effort!

Knowing our baseline behavior helps too, so we can monitor and measure improvements.

Yet even with extensive practice and re-training, heightened emotion can sometimes overwhelm all our efforts at cortical inhibition, bringing some impulsive habits back.

LEARN MORE: A Dive Into Habits

LEARN MORE: Learning through mistakes!

LEARN MORE: A neurosymphony of skills!

LEARN MORE: It’s Just Like Riding a Bike…Except It’s Not!

LEARN MORE: How to Form Good Habits? A Longitudinal Field Study on the Role of Self-Control in Habit Formation

LEARN MORE: Creatures of Habit: The Neuroscience of Habit and Purposeful Behavior

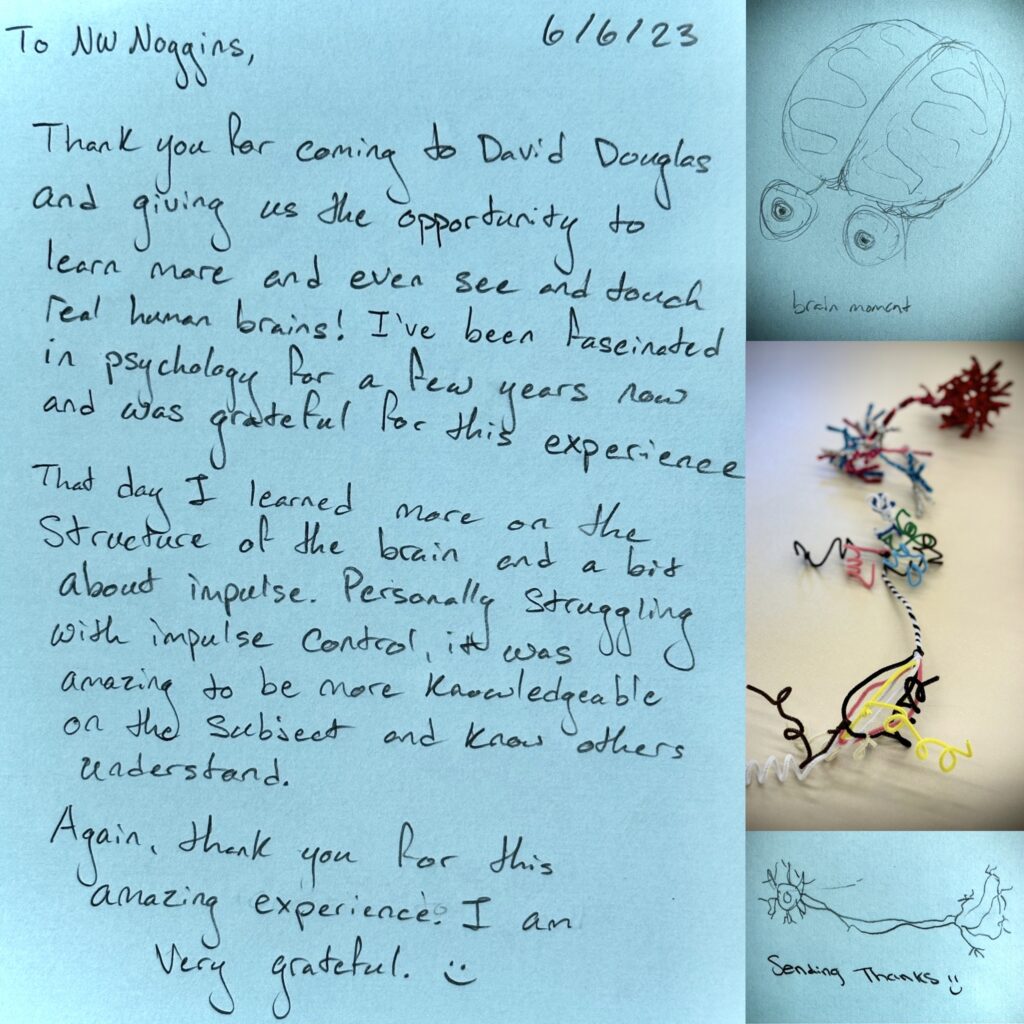

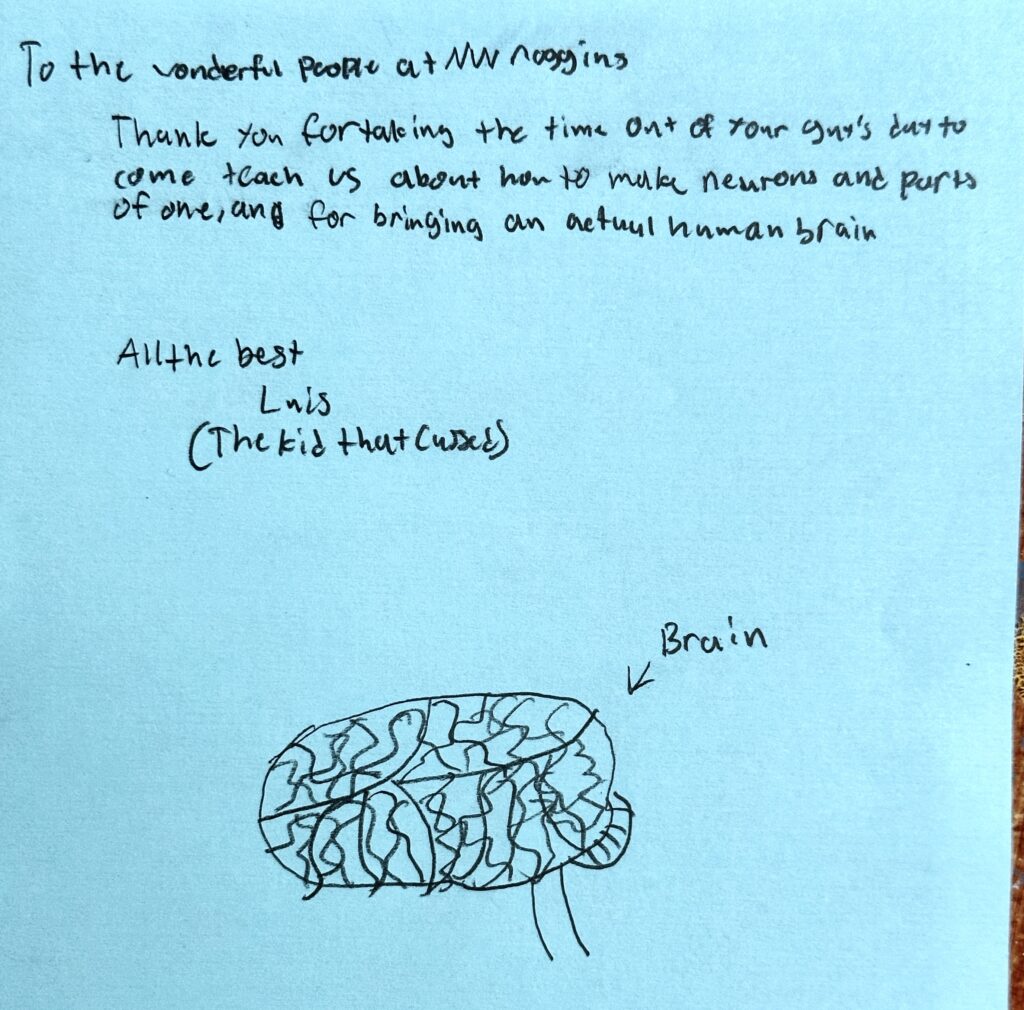

One student entertainingly described his efforts to reduce the number of times he cussed. He dropped from a baseline of around 50/week to 38! He was most effective when stopping to pause and think about his actions, and consciously override his habitual urge to swear. Yet when he played rugby, and was in the emotional heat of a brawling game, the curses were much harder to stop.

Habits of academia

Faculty (usually tenured), along with foundations and other grant-granting organizations often ask for “evidence” that we reach K-12 students through our entirely volunteer, arts-integrated, interdisciplinary brain outreach, and positively influence their understanding, interest and sense of belonging and engagement in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).

And what they want, almost every time, like a habit – is a SURVEY.

What academics apparently (and impulsively) love more than anything is a pre-test, followed by a post-test, to clearly demonstrate the benefits of a targeted (and sometimes trademarked and purchasable) intervention.

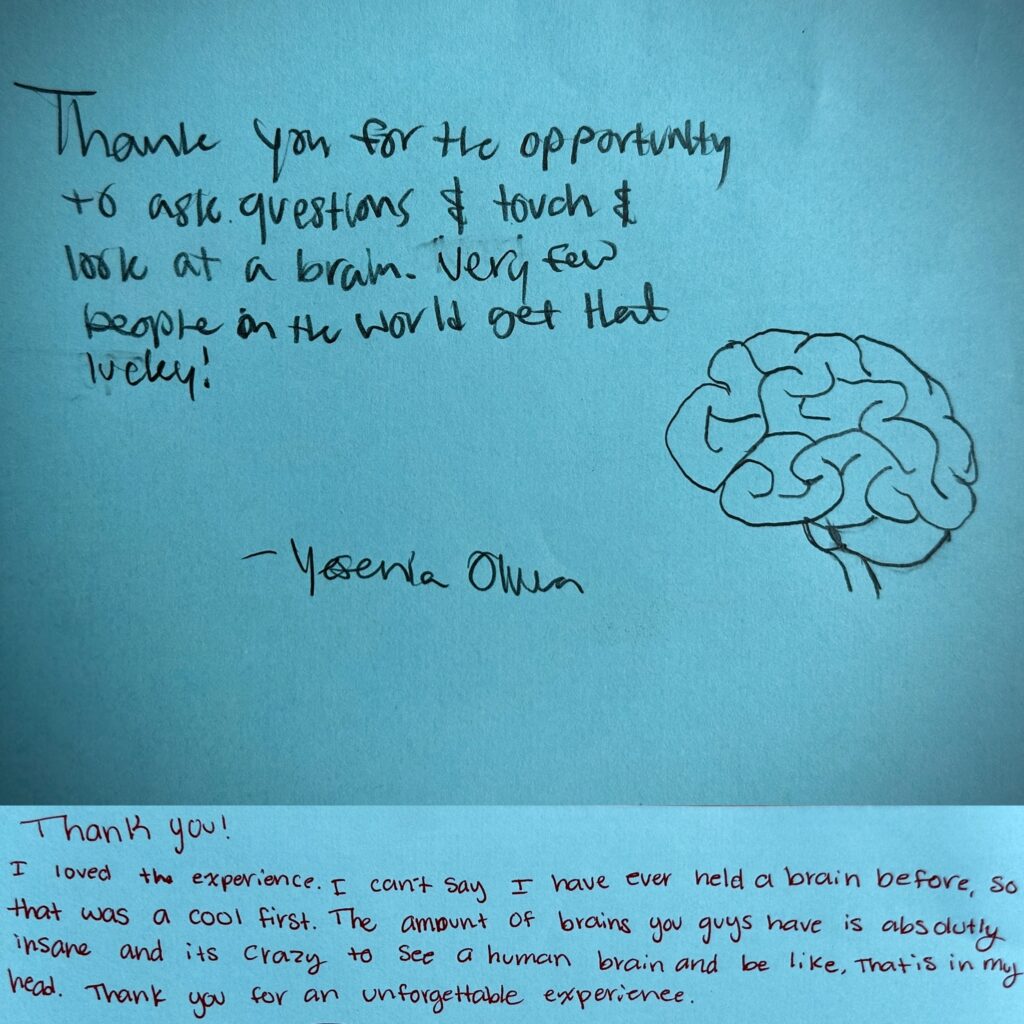

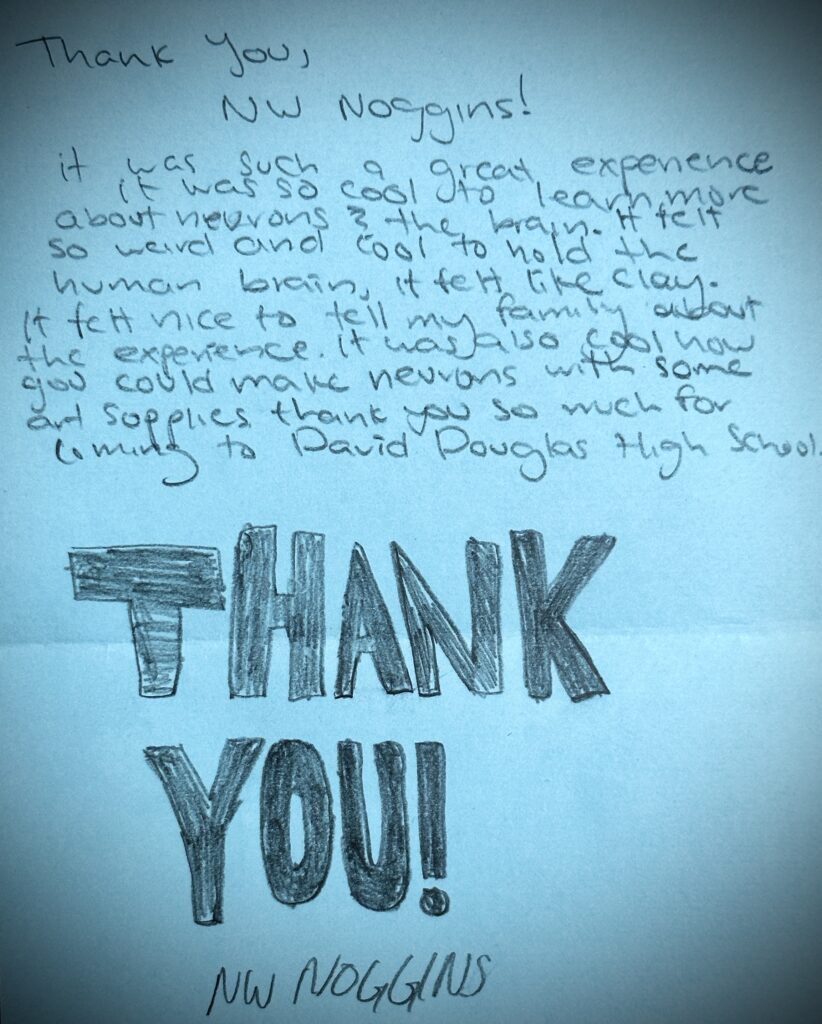

But is a survey best? What if it feels like a test? Are there less habitual, less scripted, more accessible, novel, engaging and participatory alternatives that might work better, reach more people and tell you more?

Many of the students we’ve met – including those with backgrounds NOT currently overrepresented in STEM (unlike the vast majority of academics) – haven’t always had positive experiences with testing of any sort. Some tests, particularly standardized tests, were designed to intentionally exclude more diverse participation in higher education and research.

LEARN MORE: How to Create a Bad Survey Instrument

LEARN MORE: Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently)

LEARN MORE: Expanding Underrepresented Minority Participation

LEARN MORE: Trauma-Informed School Programing: Applications for Mental Health Professionals and Educator Partnerships

LEARN MORE: Epistemic exclusion: Scholar(ly) devaluation that marginalizes faculty of color

LEARN MORE: Universities Say They Want More Diverse Faculties. So Why Is Academia Still So White?

LEARN MORE: Scientific Racism and North American Psychology

LEARN MORE: The Racist Beginnings of Standardized Testing

We once gave a survey during our first visit to a Portland public school, and everyone’s face just fell. But when we ask people what they already know or want to explore, and invite them to create their own brain-related art – clear demonstrations of engagement, skill and learning appear!

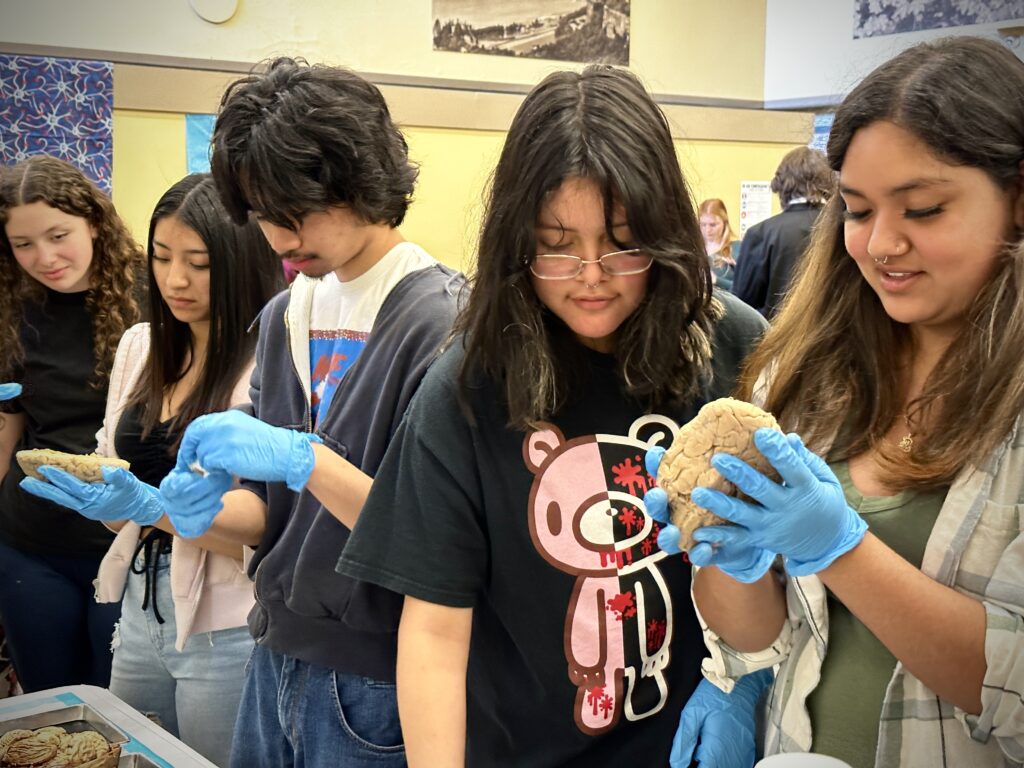

In that sense we already have mountains of evidence to show that our interdisciplinary approach is effective, from the countless photos of enthusiastic students wrangling noggins, crafting brain cells and asking extraordinary, informed, insightful and challenging questions of volunteers.

LEARN MORE: Noggin Bloggin

LEARN MORE: How do we know how we’re doing?

LEARN MORE: Thankful for brains

We also have posts written by teachers and our own Noggin volunteers, from their multiple outreach visits to schools and other public spaces. We are asked to return to the same places again and again, deepening our collaborative connections, and sometimes even influencing policy changes that directly benefit the local community.

LEARN MORE: Hey Vancouver: Let Kids Sleep!

LEARN MORE: What will your students remember in five years?

LEARN MORE: “Tomorrow is Brain Day!”

LEARN MORE: Gray Matter in Grants Pass!

LEARN MORE: Best brain scientists!

LEARN MORE: How do we know how we’re doing?

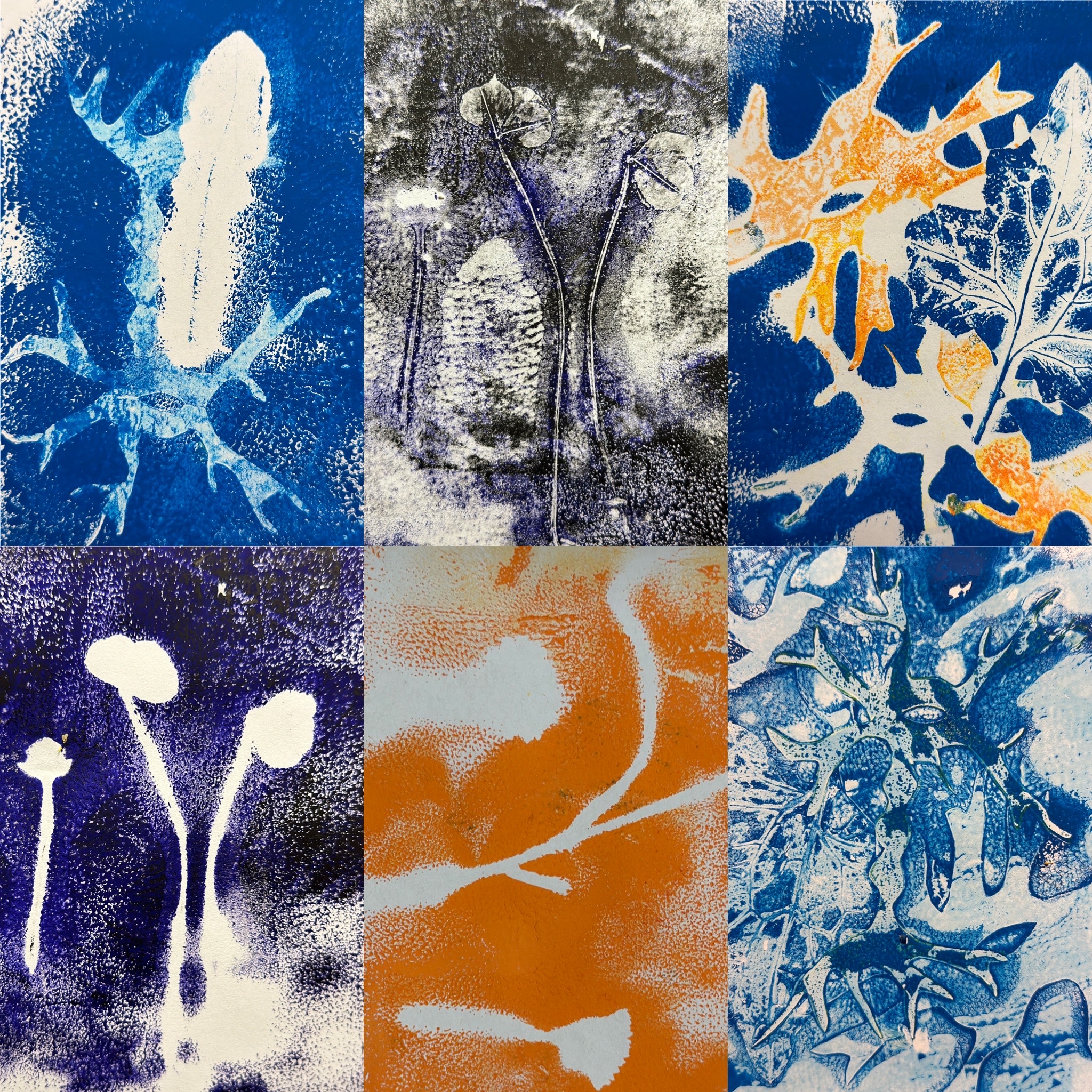

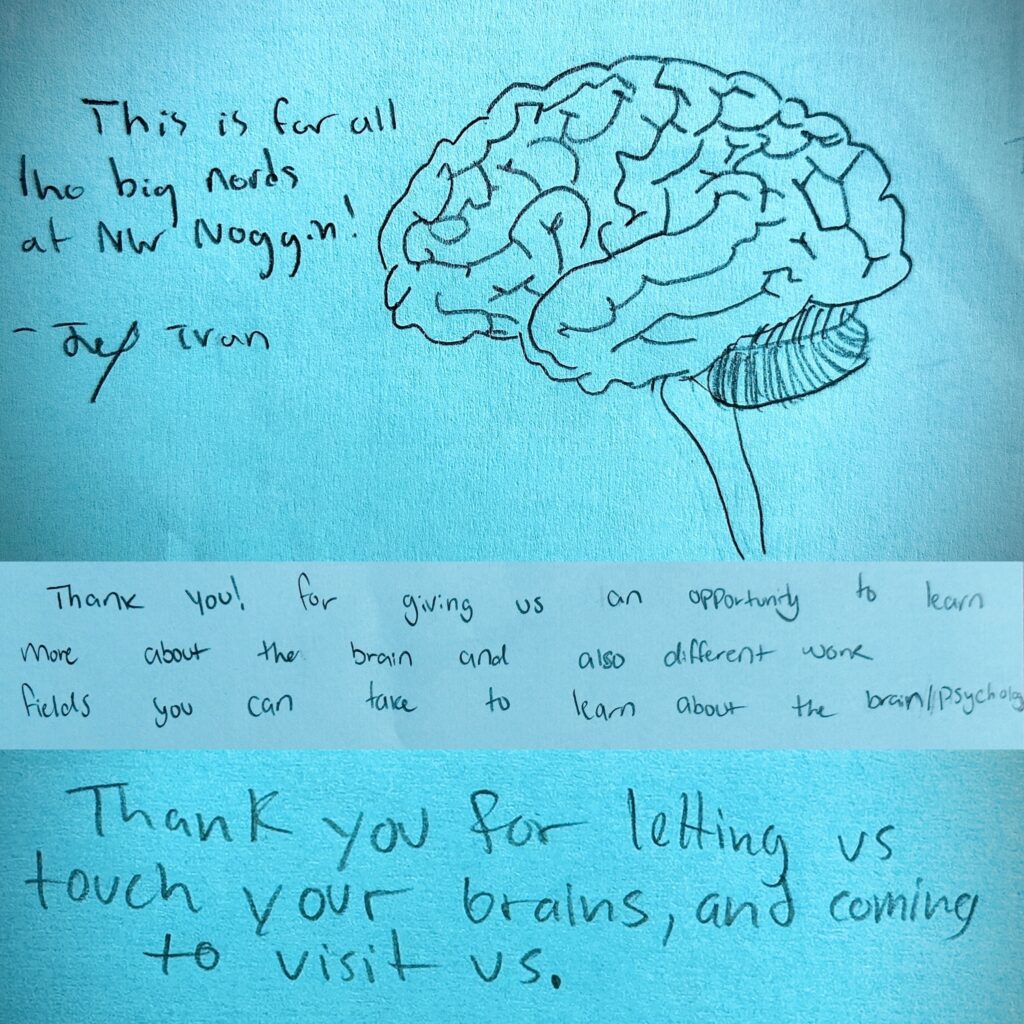

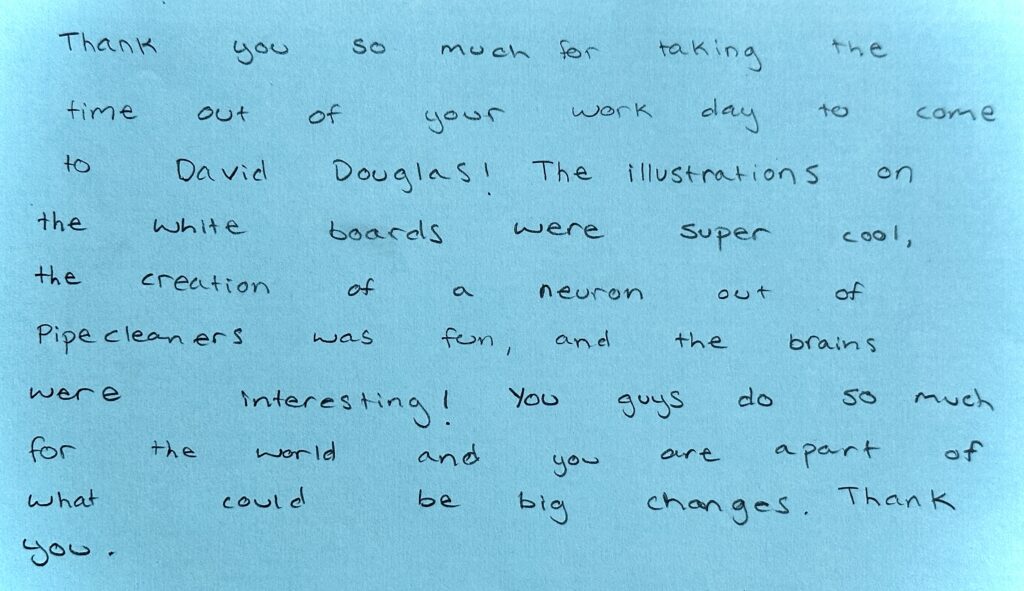

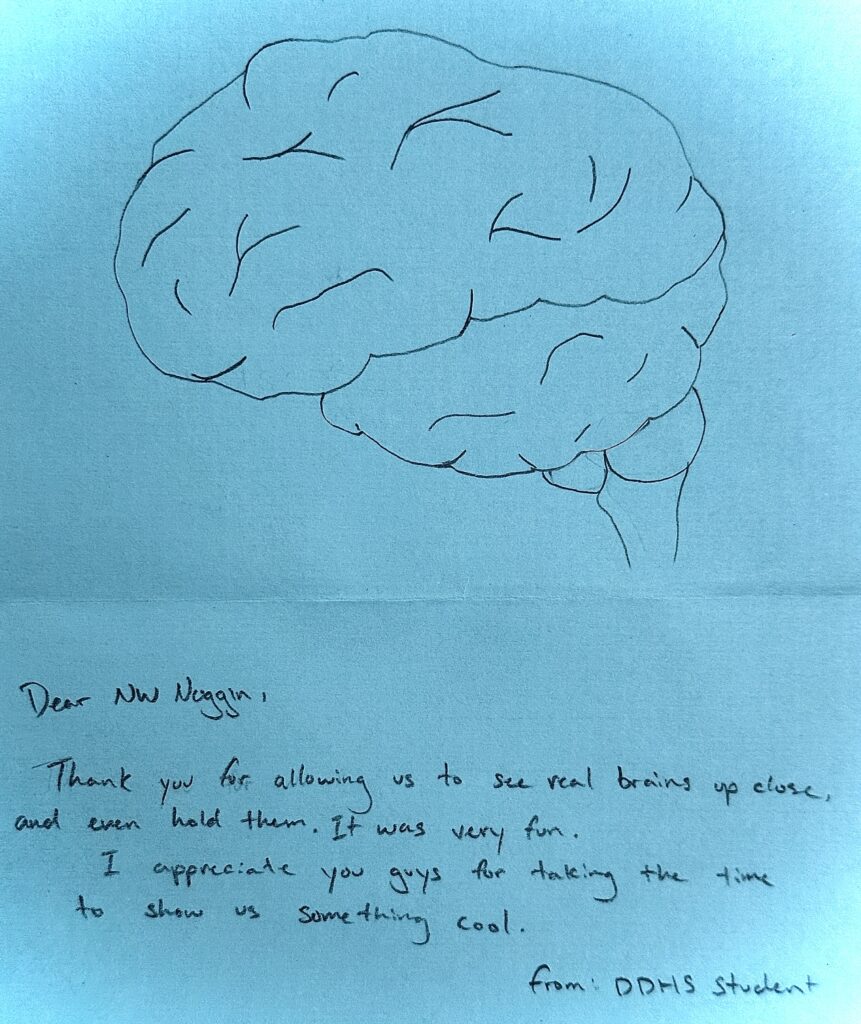

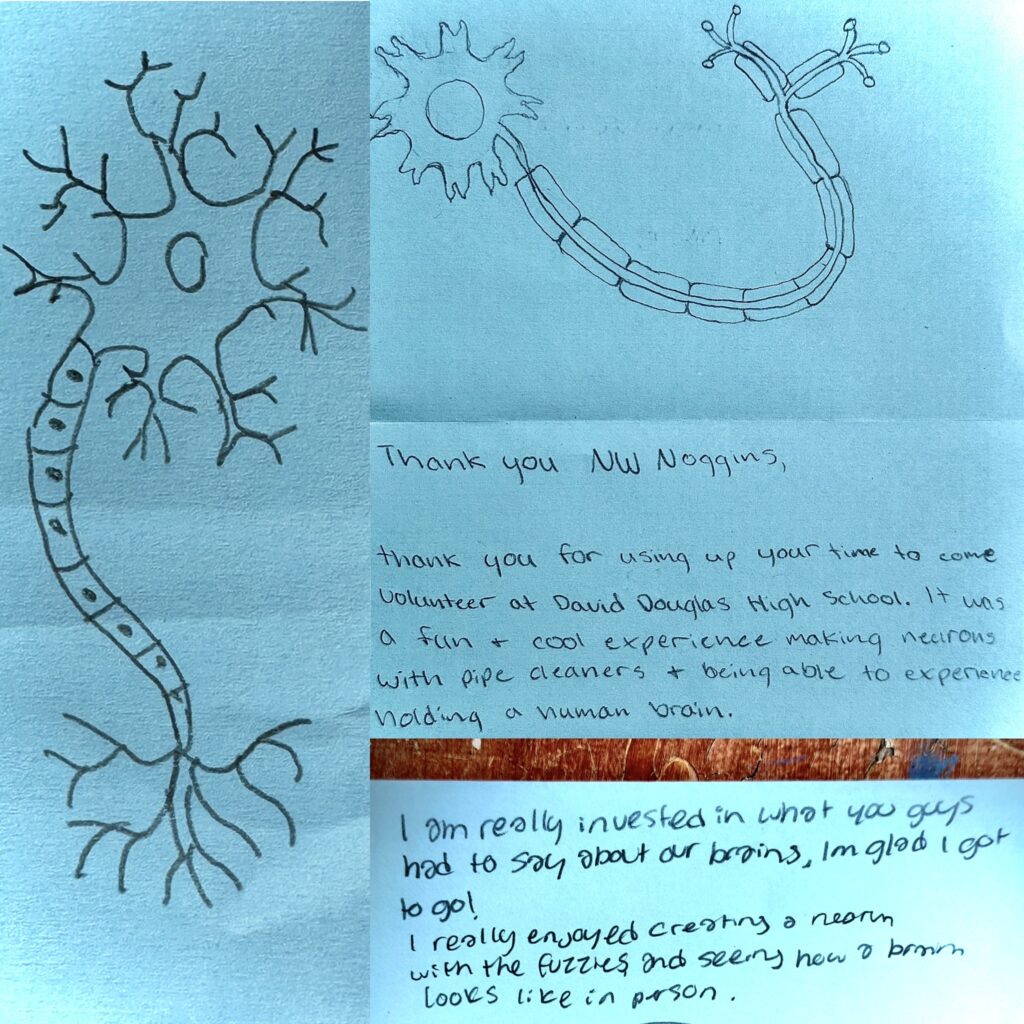

And what about the incredible artwork made during Northwest Noggin events?

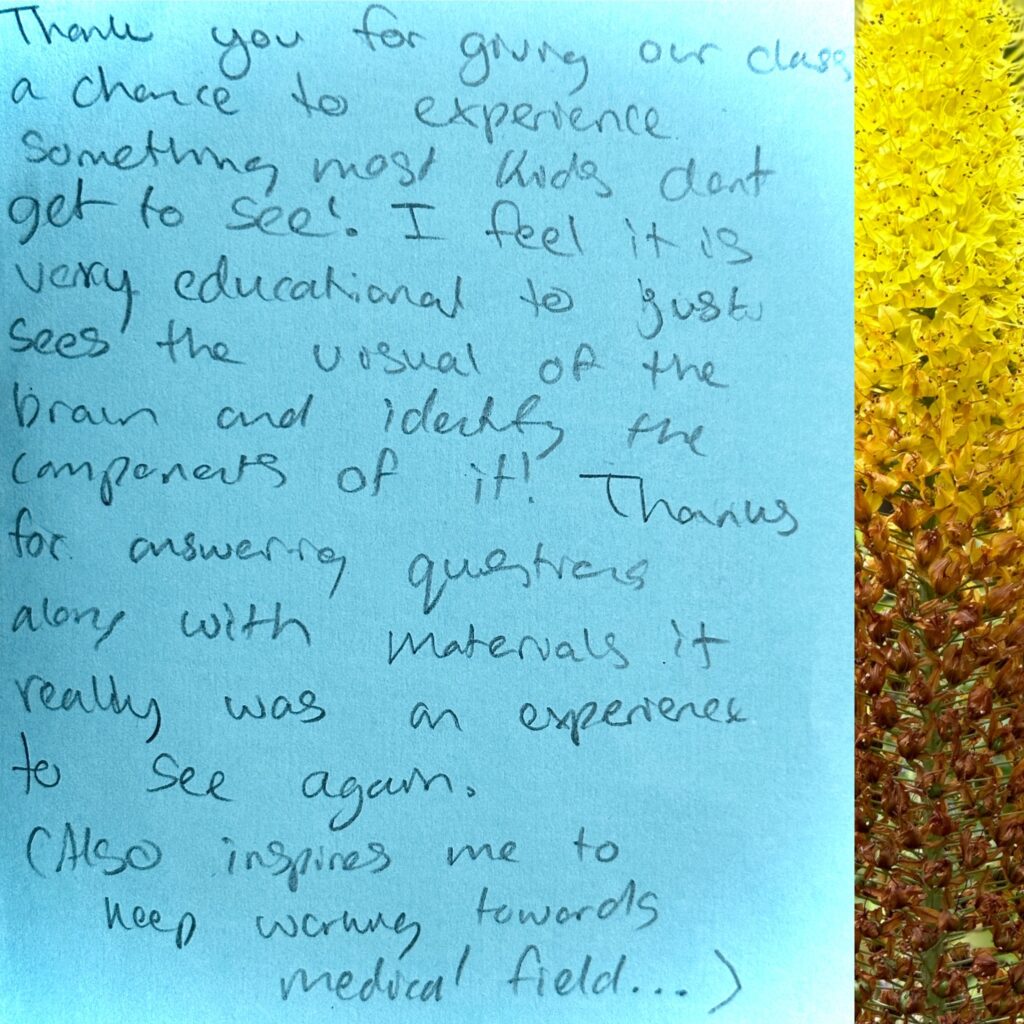

And then there are the THANK YOUs!

From David Douglas

Our gratitude goes out to Tracy and Heather and their extraordinary habit-changing students at David Douglas! And thank you NW Noggin volunteers for sharing your wonderful enthusiasm and expertise in interdisciplinary neuroscience with your community. Without surveys. Or tests.