Post by Amy Lin, undergraduate in Public Health Studies: Pre-Clinical Health Sciences pursuing an Interdisciplinary Neuroscience minor at Portland State University.

Getting into research

I knew that I was interested in medicine and biomedical science at a young age.

Growing up, I attended many medical summer camps that fed into my interests.

Although many people know about occupations such as doctor, nurse, and pharmacist, I had the opportunity to learn about research at one of my summer camps. I wasn’t sure if it was something I’d like to pursue, but it was my first time learning about the job.

Fast forward to college and a family friend had a long conversation with me about how her daughter currently worked as a research assistant. I was certainly interested, but my high school did not provide any resources and I simply didn’t know how to learn more. The idea became a thought buried deep in my brain, and at some point, I forgot all about it.

BUILD EXITO

During my freshman year in college, my mentor Courtney brought up this program on campus called Build EXITO. She had also applied, but since she was majoring in graphic design, they wouldn’t accept her since it didn’t fit the NIH requirements. During our meetings, she would often mention that it’s an excellent program to be a part of in my university years, especially since my interests were more relevant. I wasn’t quite sure what the program entailed, but I applied and was accepted.

Build EXITO “provides students with the scientific skills and understanding they need to pursue careers in a variety of biomedical fields including psychology, chemistry, biology, social work, and many more. We work to create an environment where students can experience a sense of belonging and develop their identity as scientists as they pursue research that will help make the world a more just and equitable place.” The program did so by offering weekly enrichment sessions aimed at helping us develop professional skills, research lab placements, and both research and career mentors.

Build EXITO offered me three years. Year One introduced the basics of research and what being a researcher entails. At the end of that first year, students are given the opportunity to match to a Research Learning Community (RLC). This is where students are officially partnered with a lab (either at OHSU or at PSU) and they work as Undergraduate Research Assistants on projects while receiving mentoring. Enrichment sessions are still ongoing and there are also many supplemental workshops (e.g., scholarship writing, how to write a personal statement) available for scholars. The second and third year of EXITO are quite similar with students continuing to work in their RLCs. Scholars graduate from the program at the end of their third year.

NOTE: The Build EXITO program is winding down, but there are additional opportunities for students to seek research experience, including Undergraduate Research Training Initiative for Student Enhancement (U-RISE), Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) and the McNair scholars program.

Child Language Learning Center Lab

Through Build EXITO, I was placed into the Child Language Learning Center Lab at Portland State University under Dr. Carolyn Quam from the Speech & Hearing Sciences Department. When EXITO first announced that we would have a Research Learning Community (RLC) fair to familiarize ourselves with the different labs that we could be a part of, I was certain that I wanted to do something related to child development or language learning. I had a list of 5 RLCs I was interested in, and surprisingly Dr. Quam’s lab was not on my list. I was talking to another Principal Investigator (PI) regarding bilingualism research when she pointed out that my lack of background in Spanish would not make me a good fit, however, she knew of another lab that might fit my interests more. Although my conversation with Dr. Quam lasted no more than 15 minutes, I really enjoyed the way she talked about her research and their findings, and their hopes of moving forward with the research after a pause from COVID.

I matched with Dr. Quam’s lab, and that’s where my research journey really began.

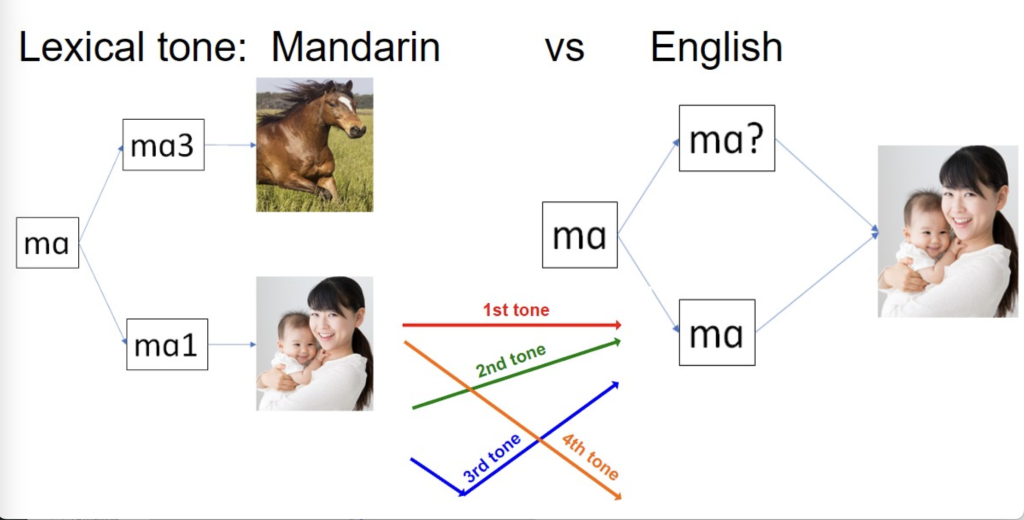

According to Quam and Creel (2017a), people who speak both Mandarin and English must pay attention to tone selectively depending on the language context. This suggests that exposure to English could potentially weaken the processing of Mandarin tones.

Eye tracking can be a useful tool in research because it allows researchers to objectively measure where participants are looking and for how long. This can provide valuable insights into cognitive processes such as attention, perception, and decision-making. In the context of language research, eye tracking can help researchers understand how participants process linguistic information and how their visual attention is influenced by different linguistic factors.

There are currently three different projects going on in the CLLC Lab, the Adult Language Impairment (ALI), Bilingual Eye Tracking (BET), and the Heritage Language Maintenance study.

I work on the Eye Tracking project because I am a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese.

The project relies heavily on testing vocabulary recognition, whether that’s clicking on images on a screen or naming images, therefore, it was important to have someone who spoke Mandarin Chinese on the team to ensure quality of responses. The lab is currently up and running despite the pause from COVID, and we are actively recruiting participants for all ongoing projects in the lab.

My Interest in Language Development

I was born in Taipei, Taiwan, and moved to the United States when I was five. Although I was immediately integrated into the U.S. education system, I didn’t graduate from the ESL program until third grade.

My parents were also concerned about me losing my heritage language and therefore I spent the majority of my weekends in Chinese school, which I absolutely hated, because I couldn’t possibly imagine why I had to go to even more school. However, as I grew older, I noticed that a lot of my friends who had similar backgrounds were not at the same Mandarin proficiency level as I was.

In fact, it was also as if they never really had the exposure to the language. Seeing them communicate with their parents in limited Mandarin was somewhat sad to see and I slowly grew to be extremely thankful that I still spoke the language.

This is something we refer to as attrition; the process of losing a native or first language.

Research has found that attrition is usually due to both isolation from speakers of your native language and the acquisition/use of a second language. Mandarin-English bilingualism is a unique type of bilingualism because of the contrasting linguistic characteristics of the two languages. Mandarin is a tonal language, which uses pitch to distinguish between words and meanings, whereas English is a non-tonal language that relies on stress and intonation to convey emphasis and nuance.

Despite the growing number of Mandarin-English bilingual speakers worldwide, research on bilingualism attrition in this population is quite limited.

There have been studies that have explored factors that contribute to bilingualism maintenance and loss in other language pairs like Spanish-English or French-English, but few have focused on Mandarin-English.

LEARN MORE: Attriters and Bilinguals: What’s in a Name?

LEARN MORE: First Language Attrition: What It Is, What It Isn’t, and What It Can Be

LEARN MORE: Lexical attrition in younger and older bilingual adults

Bilingual Eye Tracking (BET) Study

The Bilingual Eye Tracking study expands on previous research that was conducted by Dr. Quam and Dr. Sarah Creel at the University of California San Diego, where they tested Mandarin-English bilingual adult participants.

The primary goal of the research is to learn how experience with English for native speakers of Mandarin Chinese affects sound processing in their native language.

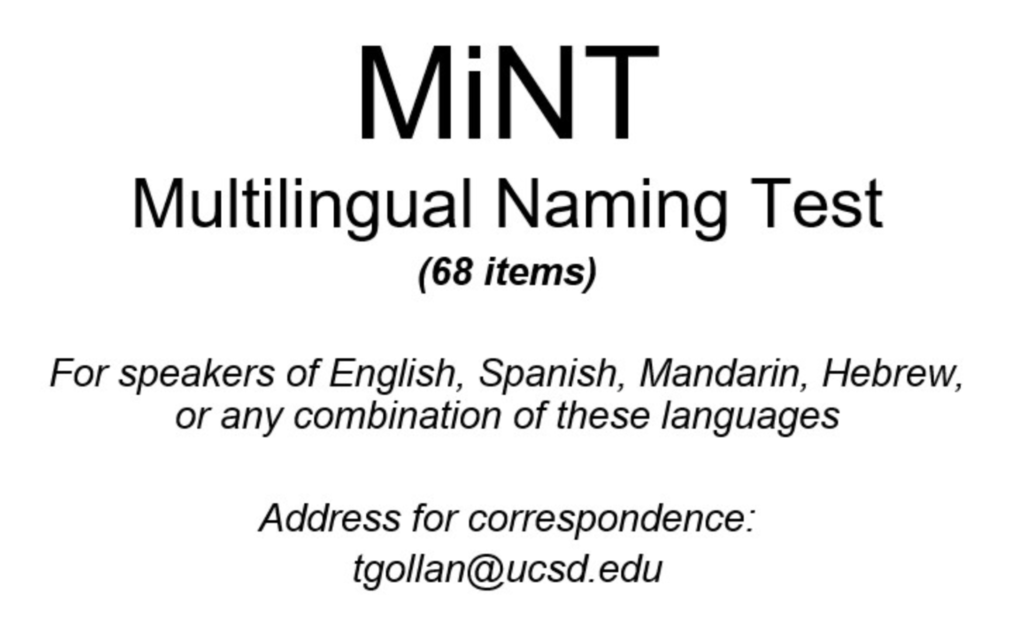

There are three methods we use to test for this: Eyelink Eye-tracking, Multilingual Naming Test, and the Bilingual Dominance Scale.

In order to qualify for the study, participants must be 18 years of age or older, have learned Standard Mandarin from birth and learned English later, or have learned both Standard Mandarin and English from birth, self-identify as knowledgeable in Standard Mandarin and English, and must be currently using both languages regularly, and have ALWAYS been exposed to Standard Mandarin MORE than any other Chinese dialect or tonal language. It is very important that participants meet all of the requirements stated above, as we would have to omit their data later on if we discover they don’t qualify.

What Testing a Participant Looks Like

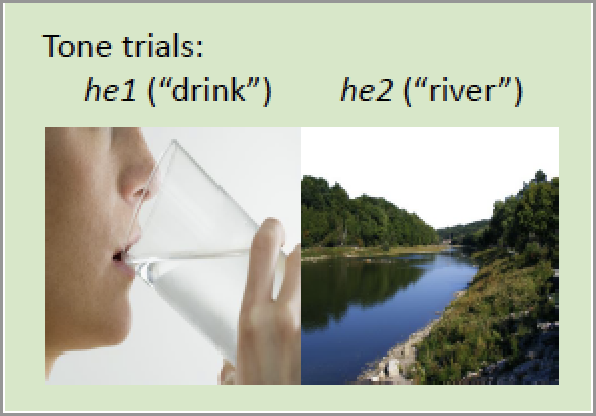

Participants are asked to come into the lab, since many of our tests (including eye tracking) require in-person technology. Participants are asked to sit down in front of a computer. They are then asked to go through a test phase, in which Mandarin instructions are presented and they are given a rundown of what tonal phrases correspond with which image.

We use our eye tracking equipment to follow where people look on screen, so participants are asked to put a target sticker on their forehead for proper calibration of their pupils.

In the image below, you see that both the pupil and cornea box need to show green to ensure proper calibration. If either one is glowing red, then you can adjust with the buttons on the top left as needed until thresholds are within acceptable range. The entire section takes roughly 45 minutes to complete, as the participant is repeatedly played a tonal phrase and asked to select between two pictures. Once the participant is finished with this section, we move on to the Multilingual Naming Test (MiNT).

For this study, gaze samples were used to determine the location of the participant’s visual attention from 200 to 800 milliseconds after the start of each trial. This time period was chosen because it represents the earliest point at which a participant can respond to the stimuli and the point at which the overall accuracy asymptote was reached.

Another measure was reaction time. RT analysis provides insight into both participant accuracy and processing time. Since overall accuracy rates were high, this data may differentiate Mandarin-dominant participants from English-dominant ones. A more Mandarin-dominant speaker would require less time to achieve high accuracy than a less Mandarin-dominant speaker.

The MiNT vocabulary test is done twice, once in English and once in Mandarin. Depending on the participant number, we will alternate which language is done first. The MiNT is essentially a slideshow of images that begins with familiar items such as “hand” and “cloud” and ends with more difficult words such as “hinge” and “axle.” Depending on whether a participant is able to name the image immediately or if any semantic or phonemic cues are required, a score is applied and recorded for later analysis. A semantic cue would be a sentence about what the item is or where it may be used, whereas a phonemic cue is the first syllable, which can be more direct in helping a participant find the word.

The Bilingual Dominance Scale (BDS) is another tool used in language-related studies.

BDS a survey of language history and present use, that asks questions like “At what age did you first learn each language?” or “What language do you do math in?” Points are awarded to each language based on what the answers were. After the scores are compiled, the English score is subtracted from the Mandarin score in both the Bilingual Dominance Scale and the MiNT.

LEARN MORE: A quick, gradient Bilingual Dominance Scale

LEARN MORE: Bilingual Language Development: The Role of Dominance

LEARN MORE: Language Dominance Affects Bilingual Performance and Processing Outcomes in Adulthood

LEARN MORE: First Language Attrition and Dominance: Same Same or Different?

LEARN MORE: Language Proficiency and Dominance Considerations When Working With Spanish–English Bilingual Adults

When analyzing the composite scores, a positive number would indicate Mandarin dominance while a negative number corresponds to English dominance, with a larger value indicating stronger dominance in that language.

One surprising finding was that language dominance did not have a noticeable effect on participants’ gaze toward the target, which contradicted the results of a previous experiment. However, considering that our participants were predominantly Mandarin speakers, this result is not entirely unexpected.

The differences in gaze patterns across trial types were consistent when analyzed at both the participant and item levels. Contrary to our expectations based on previous data, significant differences were found between baseline and vowel-differentiated trials, rather than between baseline and tone trials or between tone and vowel-differentiated trials, as revealed by a statistical analysis (paired t-tests). The analysis of vowel comparisons is also intriguing because significant differences only emerged in the patterns of gaze fixation, not in accuracy or reaction time. It is surprising that the easy and hard vowel-contrast trials did not show significantly different results, but both were significantly different from the medium trials.

LEARN MORE: Tone Attrition in Mandarin Speakers of Varying English Proficiency

LEARN MORE: Attrition Effects in Mandarin-English Bilinguals of Varying Proficiencies

Going Forward

Our goal going forward is to continue testing participants. Our previous batch of results showed that we had a lot of Mandarin-dominant bilinguals, likely because we recruited through the Office of International Students. We would like to focus on testing English-dominant bilinguals or balanced bilinguals, with the hopes of testing 48 more participants.

For my honors thesis, I am also looking to add a qualitative questionnaire on top of the methods mentioned above to understand how the current geopolitical climate is affecting perceived Mandarin-language status, experiences of linguistic discrimination, and Mandarin use in general. Participants will answer the qualitative questions and also indicate their degree of negative emotions (i.e. fear, feeling unsafe) about the rise in Asian hate, via the Likert scale. The participants’ responses will then be analyzed through in-vivo coding.

LEARN MORE: Stop AAPI Hate

LEARN MORE: Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales

LEARN MORE: In Vivo Coding

I’m hoping to publish the findings in my honors thesis in Fall of 2023.