Post written by Kayla Townsley, an undergraduate in Biology at Portland State University and an NIH BUILD EXITO scholar

When considering a holistic approach to education the terms “Renaissance woman” and “Renaissance man” come to mind. Although a bit of a romanticized cliche, it embodied the ideal of a complete education–and a person versed in both the liberal arts and sciences. But whether it is the historical epitome of the “Renaissance man/woman,” or the modern-day “Jack” or “Jill of all trades”, there is another common phrase that suggests a detriment to this sort of all-encompassing knowledge: “An ace of all trades, but a master of none.”

Although cliches, they invite complex questions concerning current models of education. Which is better? Is it education that ostensibly encompasses a wide range of topics, or education that delves deeply into one area of thought? Do we value growth over proficiency? And does what we value in education change when we consider the background and situation of the students being taught?

There is also the consideration of a sustainable approach to education. What does that mean, sustainable education? I consider sustainability in education to be the ability to create long-term knowledge and proficiency of understanding. It’s essentially teaching students how to think critically, make connections, and come to conclusions, instead of focusing on the volume of facts they can cram into their heads within a term.

But like many things in life, curiosity and exploration of educational methodology produce innumerable questions, and often very few absolute answers. And I think it is this innumerability of questions swirling in my head that drove me to research what I consider both a holistic and sustainable approach to education: S.T.E.A.M (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics). S.T.E.A.M is an educational approach to learning that focuses on guiding student inquiry, dialogue, and critical thinking through interdisciplinary instruction, valuing both the proficiency of cross-disciplinary knowledge and understanding.

As someone who is a part of both liberal arts and S.T.E.M (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) focused higher education models, I have had the unique privilege of exploring the similarities and difference in teaching methods and the ways of thinking that they encourage. In doing so, I have personally come to the conclusion that maintaining a separatist style of education is a detriment to students; not only underestimating, but also undermining their capabilities to think outside the box and contribute innovative ideas to society.

Arts integration engages learners in thinking about information in new ways that improve retention through the cognitive neuroscience of semantics, cues, enactment, oral production, emotional arousal, and pictorial representation (Rinne, Gregory, Yarmolinskaya, and Hardiman; 2011). Retention and long-term memory are key to mastering subject matter, and arts integration has been shown to improve retention (Hardiman et al., 2012).

LEARN MORE: STEAM @ Newmark: Better schools with improv and art

But arts integration does not just improve retention; Lin et al. (2013) reported that long-term artistic training can “macroscopically imprint a neural network system of spontaneous activity…” or more simply put, long-term artistic experience nurtures new resilient neurons in the brain! (Elbert et al., 1995; Lin et al., 2013; Münte et al., 2002; Schlegel et al., 2015).

Artistic training is a form of complex learning, requiring meticulous and sophisticated organization of polysensory, motor, cognitive, and emotional elements that harness creativity. So whether it is playing an instrument, composing a poem, or painting, artistic training represents a method of teaching that encourages ingenuity and innovation. Art relies on deep emotional understanding and an ability to invoke and inspire emotions in others. Research has found that there is a link between empathy and synchrony that can increase recall abilities of an subject matter. Additionally, novelty enhances attention by engaging the brain’s alerting and orienting systems (Posner & Rothbart, 2007; Smith et al. 1978) and exploratory activities, empathetic responses, and novel approaches are intrinsic in artistic creation, suggesting that integrating art orientated teaching approaches across disciplines could help improve students mastery of content on a more profound level.

LEARN MORE: Building Creative Thinking in the Classroom: From Research to Practice

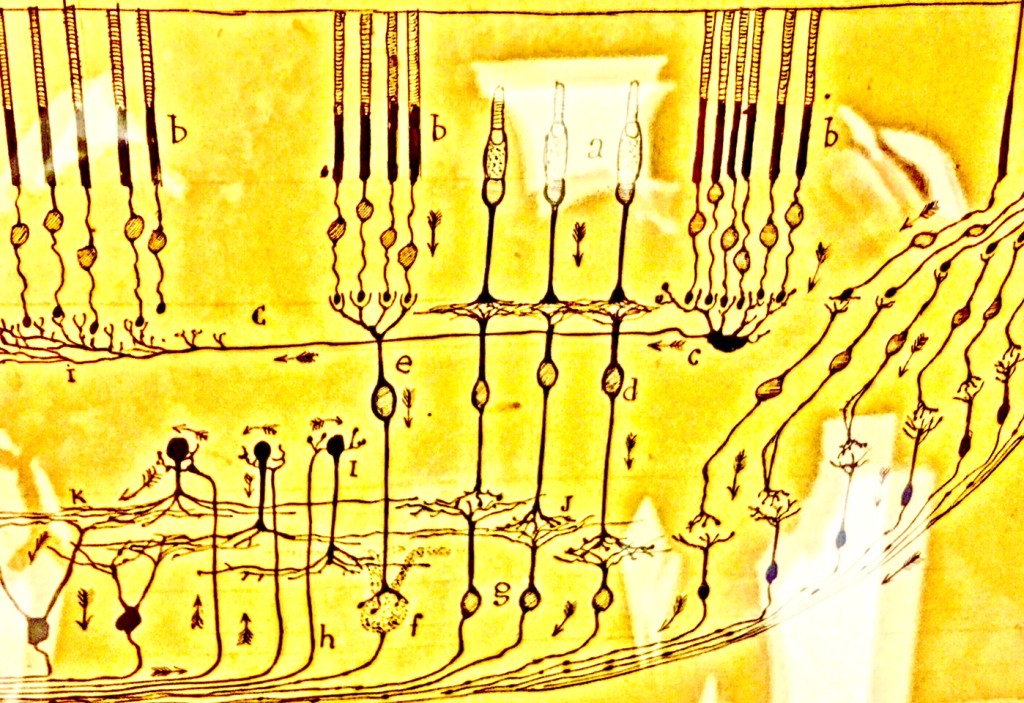

I have found, through both my current research for my thesis and from years of personal experience, that creativity is often considered a special gift and not associated with STEM fields. But just looking at the lives of famous scientists and artists proves this false; look at Einstein for an ubiquitous example, or the talented artist and ‘father of neuroscience’, Santiago Ramon y Cajal.

LEARN MORE: Cajal + Creativity @ the NIH

History has proven that we consider to be the greatest minds found balance through both scientific inquiry and artistic creation. But even without a history lesson, a growing body of research suggests that creative thinking can not only be taught (DeHaan, 2009; Dugosh, 2000), but that applying learned content through creative activities requires critical thinking that increases mastery of knowledge, regardless of subject matter (Hardiman, 2012).

Creative thinking depends on “break-through” or “out-of-the box” processing, often referred to as a “Eureka” moment (Perkins, 2002; Jung-Beeman et al., 2004) and this process actual shows different patterns of brain activity. But this does not mean people are simple born “creative”, instead it suggests that creative “insight” is related to particular physiological differences in the brain, and that these patterns of activity may be strengthened through artistic training!

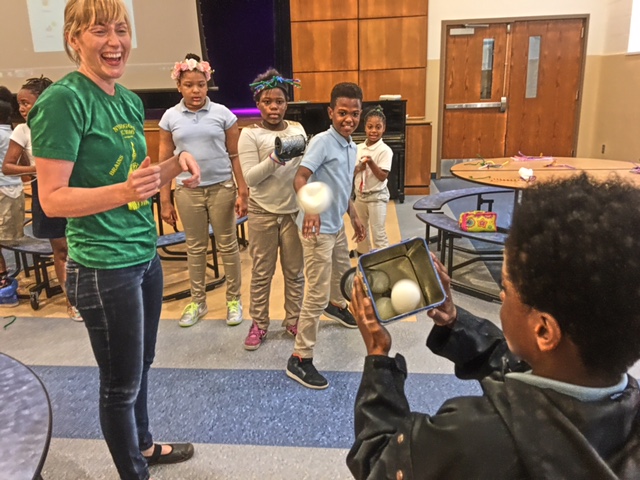

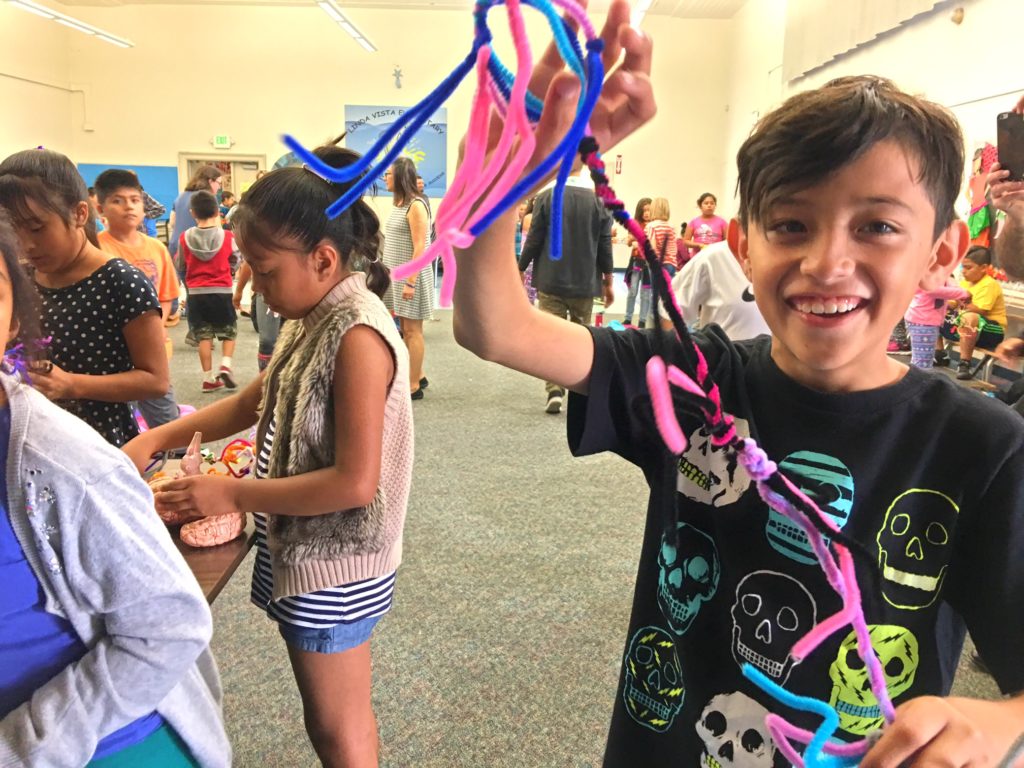

In researching the brain and how art impacts cognition, I hope to help open a world of possibilities that breaks down the rigid dichotomy of popular education models. Through neuro-scientific research, and the type of work NW Noggin is doing in schools, we are using our knowledge of the brain to actually strengthen new patterns of thinking that may help develop the innovative minds of tomorrow. As Eric R. Kandel, Nobel Laureate and strong advocate for arts integration into the sciences, stated; “an enriched understanding of the brain is needed to guide public policy. Particularly promising areas are the cognitive and emotional development of infants, the improvement of teaching methods, and the evaluation of decisions…”

“But perhaps the greatest consequence for public policy is the impact that brain science and its engagement with other disciplines is likely to have on the structure of the social universe as we know it” (Kandel et al., 2014).